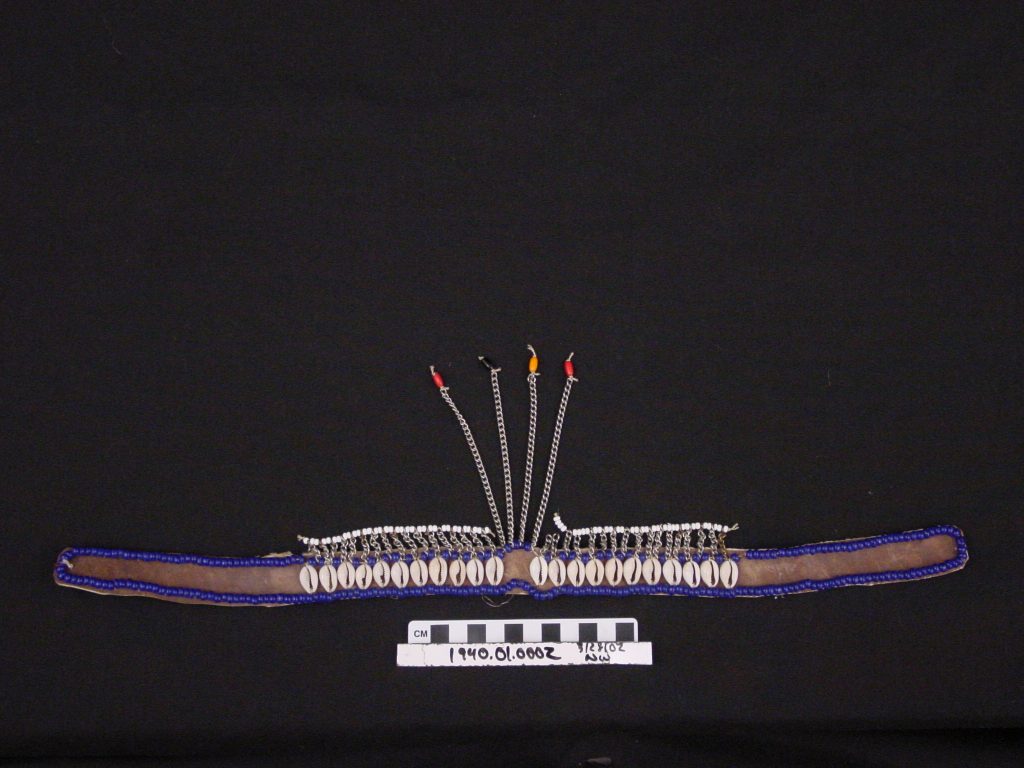

Girl’s Circumcision Headdress from the Maasai culture of East Kenya, Africa, 1971. The Spurlock Museum.

This headdress was worn by a Maasai girl less than fifty years ago. Native to southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, the Maasai are a semi-nomadic people, known for living alongside animals and an aversion to eating game and birds. Because of their lifestyle, East Africa is now home to some of the continent’s finest game areas and wildlife refuges. The Maasai are also a strong patriarchal culture, led by a group of elder men and a full body of oral law. Their lives center on cattle, which are their primary food and currency, and they – unlike many other Africans – have never practiced slavery.

Peaceful, right? Idyllic, even?

This headdress tells a darker tale. Made from shells, animal skins, plants, glass, and metal, it was worn by a young girl just after her transition to womanhood. She was probably nervous, scared even. It was a huge moment in her life. Her transformation wasn’t just biological or spiritual – it was physical.

Because while undergoing the Emuratare rite of passage, and becoming a woman who could be taken seriously, she was cut. In a procedure known today as female genital mutilation (FGM), the girl was held down as her clitoris, labia minora, and part of her labia majora were removed. It was an incredibly painful surgery for which she was probably wide awake.

Afterwards, she put on this headdress for the first time.

A longstanding practice around the world, FGM is no easy topic to discuss. For many cultures, it is intrinsically tied to a gir’s transition to adulthood and ability to marry. Yet modern medical science has revealed that it has serious health consequences. FGM can cause death, and increases a girl’s risk of sepsis, fistulas, and vaginal prolapse. The scarring it leaves behind renders sex painful, and childbirth even more so.

Today, thanks to scientific evidence, the practice is slowly dying out. But science is not enough. The key to ending FGM – and the harm it causes – is in changing cultural perceptions and norms. While cutting girls in Kenya is now illegal, it continues in some communities.

Groups like Safe Kenya are working to end the practice through community education at all levels and developing alternative rites of passage for girls that do not feature FGM. Sarah Tenoi is helping end the practice in her home country, advocating for new rituals that still center on traditional Maasai culture:

She has her head shaved and is given the bracelet that signifies her graduation, but instead of being cut she has milk poured on her thighs. When she reappears, she wears the traditional headdress which symbolises that a girl is now recognised as a woman.

This symbolic ceremony is popular because we developed it in partnership with members of the community. It is not perceived as a threat to our culture. Fathers are now requesting the circumcisers who we have trained in this alternative rite because they are considered “better”. Because we are giving our community something to replace female genital cutting, this change can be permanent.

The work of Sarah, and many others, is helping to ensure that headdresses like these are no longer worn at a moment of pain and fear, but at one of hope, renewal, and celebration.

-Tiffany Rhoades

Program Developer

Girl Museum Inc.

To learn more about the traditional practice of FGM in Kenya, read this New York Times article from 1996.

Sarah’s story originally appeared in this article in The Guardian.

This post is part of our 52 Objects in the History of Girlhood exhibition. Each week during 2017, we explore a historical object and its relation to girls’ history. Stay tuned to discover the incredible history of girls, and be sure to visit the complete exhibition to discover the integral role girls have played since the dawn of time.