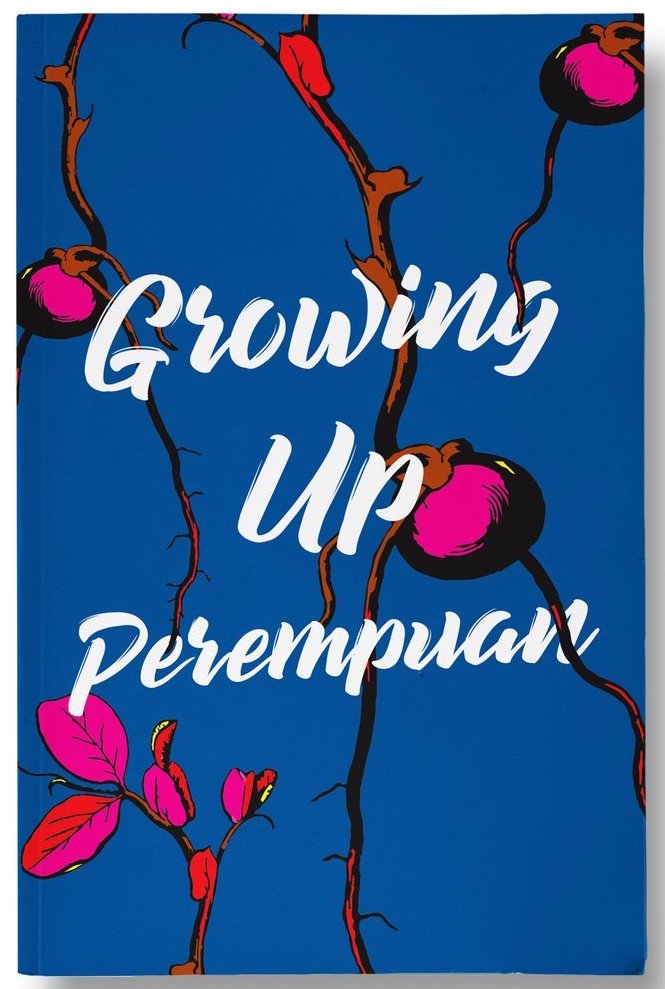

Growing Up Perempuan (Malay for ‘female/girl/woman’) is a collection of essays written by women in the Malay-Muslim community in multi-racial Singapore. The anthology covers a wide spectrum of women in the community, from young girls to women in their senior years and touches upon topics of culture, body-image, sexuality, and domestic and sexual violence. In this book, you’ll find satire, horror and coming-of-age stories and harrowing accounts of abuse and more. Growing Up Perempuan is a book that reminds us that there are many dimensions to being a woman, regardless of the labels assigned to us. I didn’t read this book in one sitting and instead read it over the course of two weeks. There is something about books like these that make me feel like I should savour the stories in them.

I’ve picked out some of my favourite stories and bits that I found interesting. The first is an essay ‘Horror Stories for Little Girls’ by an author who simply goes by the name Ham. This is easily my favourite because 1) I am a fan of horror stories and 2) I found this to be incredibly relatable. The essay highlights the link between superstition/horror and the female body in my community. Growing up, I’ve never really questioned the nature of the tales of horror and folklore that were told to us. But like Ham, I’ve always wondered why so many of these stories seem to restrict and demean women. Ham describes the chilling sensation of a young girl’s imagination, fear and regret as she walks back home from a night out with her friends because she menstruating. As young girls, we were led to believe that our periods are nasty and befouling, and a “magnet for everything unseen and unwanted”. That a figure in white, usually with long black hair would be perched on the roof of bus stops, high places, in stairwells and corridors waiting to catch you unawares. Although, you’d be aware of her presence because you would have noticed the light, sweet fragrance in the air. Ham recognises that society projects its anxieties onto the female body and this manifests into ghost stories. These ghost stories are often about females and reflect a worrying obsession with women and their bodies that we’d be objectified even after death.

Another illuminating essay was ‘Zinaphobia: Our love-hate relationship with sex’. Zina refers to the Islamic legal term that means illicit sexual relations, and in most cases refers to extra-marital sex or adultery. Here, the author unpicks a conservative society’s attitudes towards marriage and sex. She also identifies the loopholes in idealising the notion of marriage that has become a means to police and control sexuality, as well as questions the lack of comprehensive sexual education among youths.

Interviews and stories of women and girls who otherwise do not have the necessary means (language, tools or social capital) to tell their stories are what make this book noteworthy, in my opinion. From accounts of girls who grew up in the foster care system to the raw narrative of a sex worker opening up about her abusive past and challenges, I could only sympathise with. Other essays, such as ‘A Muslim Woman’s Guide to the Workplace, Part II’ had me laughing out loud while also cringing as the author fights against negative stereotypes of women wearing the tudung (hijab/veil) in her workplace with her wit and humour.

Growing Up Perempuan is a sobering read, and has made me realise that I have grown up quite fortunate, and in some ways, more privileged than some of the women and girls whose stories have been immortalised in this anthology. And as Ham eloquently put in her essay, I too believe that “words have power and, by extension, so do stories. If they have the power to contain us, perhaps, we can also tell stories that liberate us”. I’d recommend this book to anyone who is curious, despite some of its nuances that could potentially get lost in translation. But if you can get your hands on a copy, I guarantee it would be a riveting read.

-Syirene Mahdhar

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.