https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/1810-edition-of-little-red-riding-hood

The story of Red Riding Hood is one that most people around the world will have heard. The popular tale we know today is based on both Le Petit Chaperon Rouge (Little Red Riding Hood) by Charles Perrault, with adaptations from Rothkäppchen (Little Red Cap) by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. However, the potential origin of the story might go back as early as the 2nd century CE.

In his anthology Description of Greece, Greek geographer Pausanias wrote the story of the ‘Hero of Temesa’. On his way back from Italy, a boxer named Euthymus came across a town who were terrorised by a spirit in a wolfskin. Originally one of Odysseus’ men, the ‘hero’ had been stoned to death for violence against a maiden, the Greek phrase for a young, unmarried girl. To appease this violent spirit, the town would offer the most beautiful girl each year who was brought into his temple shrine. Euthymus was asked to help and hid in the temple alongside the maiden on the evening of the offering. When the spirit arrived, Euthymus chased him to the sea where he fell in and disappeared, never to be seen again.

On its own this might seem very different to Little Red Riding Hood, but as we look closer we can start to see similarities between the two.

The idea of a werewolf wasn’t new, even in ancient Greece. First dating to The Epic of Gilgamesh written over 4000 years ago, they became especially popular in the 5th century BCE. Greek historian Herodotus wrote about the Neuri, a tribe in Scythia (now in Russia) who changed into wolves throughout the year. In parts of Greece, Zeus was worshipped as ‘Lycaean Zeus’ who was both a protector and tyrant.

Tales of ‘loup garou’, ‘lycanthropes’ or ‘werewolves’ swept again across Europe in the Middle Ages, particularly in France and Germany during the late 16th century. The earliest modern record of a suspected werewolf was in 1521 in Poligny, France, when a traveller was attacked by a wolf. The victim chased the animal and found a man covered in blood, who believed himself to have been the wolf. Werewolves were believed to be linked to the devil, much like witches, and a wave of lycanthrope trials took place at a similar time. Outlaws played on this fear and wore wolfskins over their armour, as members of the Neuri tribe most likely had centuries earlier.

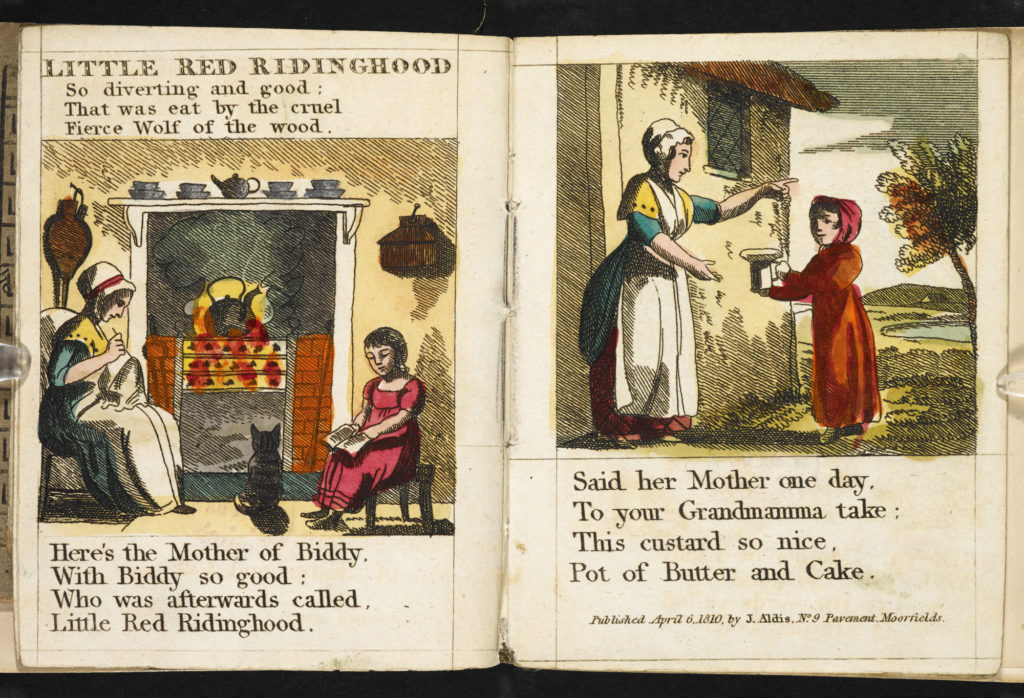

Le Petit Chaperon Rouge pulls on this folklore in 1697 and describes a “little country girl, the prettiest creature who was ever seen”. After meeting a wolf in the forest, he races her to her grandmother’s house and lures her inside. Perrault gives us the well-known “all the better to eat you up with, my child” and the story ends with a moral. “Children, especially attractive, well bred young ladies, should never talk to strangers for if they do so, they may well provide dinner for a wolf.”

The link between these two tales is a beautiful young girl who is attacked in a building by a wolf. But in 1812 the Grimm Brothers took this a step further.

Rothkäppchen makes no mention to the beauty of the child, but instead calls her a “sweet little girl”. The story largely follows the same plot; Little Red Cap takes some cake to her grandmother and comes across a wolf in the forest. Here she is not challenged to a race, and instead picks some flowers for a bouquet. This is the first variation of the modern story that ends with a rescue, which is very different for a Grimm retelling. In one version a passing huntsman filled his belly with stones instead which killed him when he tried to run away. In the other version, the wolf didn’t get to the grandmother’s house in time and was waiting on the roof for Little Red to leave. They tempted him to look over and when he fell he slid into a trough of water and drowned. While ending happily for Little Red Cap and her grandmother, these especially hark back to the Greek story of the wolf being stoned or disappearing into the water.

Whether this fairy tale was inspired by the ancient Greek tale, we will never know for sure but it is clear that the idea of a werewolf has seeped into popular literature for thousands of years. Particularly between the 17th and 19th centuries, these stories were aimed as a warning to girls and young women of the dangers that can come from men.

-Devon Allen

Volunteer

Girl Museum Inc.