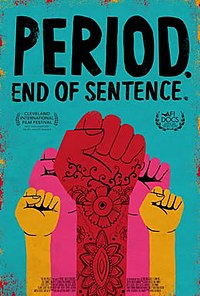

SAt the most recent Oscars, a film about menstruation won the award for best documentary short subject. The director Rayka Zehtabchi said as she accepted the award; “I’m not crying because I’m on my period or anything, I can’t believe a film about menstruation just won an Oscar!” Though an undeniably happy moment, her shock is a startling reminder of just how rock-hard the taboo is that she is working to break, and how little we are accustomed to seeing one of the most natural bodily functions discussed in the open.

For those of you who don’t know, Period. End of Sentence is a 26 minute Netflix documentary following the installation of a pad-making machine in the village of Kathikhera in India. Under the Pad Project — an organisation which provides sanitary products to developing countries — a North Hollywood student group used crowdfunding to send the machine to the village, alongside Zehtabchi to document its effects. Local women were shown how to use the machine, and in no time they began churning out homemade sanitary products under the brand name ‘Fly’ — because they want to see women ‘rise and fly.’ The unit currently employs seven women, working six days a week to produce around 3,600 pads each week.

In following the development of this business, the film showcases not only the drive of these women but also the staggeringly deep-seated stigma that still surrounds something which, for most women, is a part of daily life.

The film opens with footage of people around the village responding to questions about menstruation — in some instances, the ignorance shown is truly mind-bending. While the girls interviewed simply laugh and hide their faces, most of the men who populate the short film are utterly clueless. One, when asked what a period is, says he thinks it is a ‘disease’ that mainly affects women, though he’s not quite sure. Only a select few speak unashamed of the reality, with the common response being to smile, uncertain as to whether or not it’s a trick question. According to the pad-making machine’s inventor, Arunachalam Muruganantham, currently only 10% of women in India use sanitary products. Instead, it is commonplace for women to use dirty scraps of material, leaves or even ashes to stem their flows.

When considering this ignorance, coupled with a lack of access to clean sanitary products, it is no wonder that many women face a wall in society — one that is so frustratingly needless. While the film does offer a vision of hope in Fly’s progress, a feeling of sadness remains, because there is still so much to do.

As producer Melissa Burton said at the awards ceremony, “a period should end a sentence, not a girl’s education.” Yet for too many young girls around the world, the path to education is blocked by the simple obstacle of menstruation.

A 2016 UNESCO report estimated that in Sub-Saharan Africa, one in ten girls miss school during their period — equating to 20% of any given school year. The World Bank estimates that nearly one million girls in Kenya do not go to school because they lack access to sanitary pads, while 30% of girls in Nepal and Afghanistan report missing school during periods. In India, more than 20% of girls drop out of school entirely after reaching puberty. It is not only education that they are excluded from, but from many religious and social events due to the perception that periods make girls ‘unclean’ or ‘impure.’

There is also the more severe health and human rights issue of young women being banished to ‘menstruation huts’ during their periods in countries such as Nepal, with numerous reports of these girls dying from infection, cold, or animal bites while in seclusion. While the practice has been outlawed, it is still widespread in communities, and law enforcement are reluctant to intervene due to the perception of periods being a family issue.

For Zehtabchi, ending the stigma begins with enabling dialogue around it. Speaking to Glamour, she said; “I want viewers to realize that empowering women worldwide really starts with beginning with opening up the conversation around menstruation. We can implement feminine hygiene, but first we have to break the taboo.”

What gives the film its punch is the effect that such a simple product can have. Supporting menstrual hygiene and education matters not only on the human level of caring for these women and girls, but also on the global scale of enabling social and economic growth. It can contribute to achieving a number of the Sustainable Development Goals including education, gender equality, and clean water and sanitation. UNICEF has previously noted the larger health benefits that come with educating women and girls, including decreases in maternal, infant and child mortality rates, as well as poverty.

It is also important to remember that it is not only in developing countries that stigma is faced. Though these provide extreme examples of the subject’s taboo nature, we cannot take the high ground and pretend menstruation is as fully embraced as it should be in Western society. The very fact that Zehtabchi was herself amazed at a film about periods winning an award shows how unused we are to seeing the topic discussed in the open. Though we should rightly feel shock at the extent to which women are excluded in some societies, we should also turn inwards to consider our own attitudes. While we are on the right path, we still have a long way to go. As the inventor of the pad-machine Arunachalam Muruganantham says; “The strongest creation created by God in the world: not the lion, not elephant, not the tiger. The girl.” It’s time we celebrate every aspect of women, and start living up to the belief of people like Muruganantham.

-Scarlett Evans

Manager, Contemporary Art

Girl Museum Inc.