Music Period: Romantic era (1830 – 1900)

Location: Leipzig, Germany

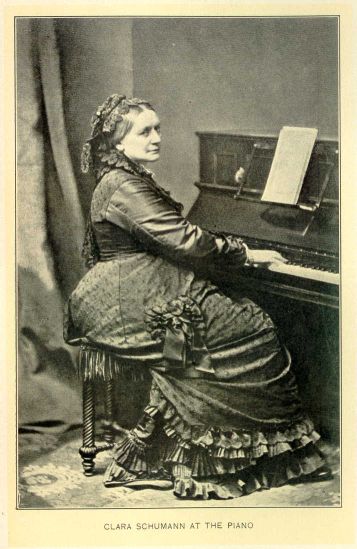

Claim to Fame: One of the foremost pianists and greatest performers of the nineteenth century.

With audiences in raptures over her music, Clara toured extensively towards the end of the decade. She produced many new works for her programmes and several published works appeared in 1833. These included Romance variée, which she dedicated to Robert Schumann – a young student now living with the Wieck family. All her performances received thunderous applause and Clara would boast that she beat her record of thirteen curtain calls with “four curtain calls after every piece (which was against the law)”. She remained absolutely certain of what it took to please an audience throughout her life. Yet, her belief in Robert Schumann’s genius compromised this many a time. For Clara, Robert was the best person to judge her own work, and she would rely heavily on his critique. On the other hand, the ability to know what an audience wanted helped Clara in other ways. She was able to advise Robert as to the appeal of his compositions to an audience. It is often underestimated just how much influence Clara had upon Robert Schumann and his music. Clara supported Robert in his own struggle to write music, just as he would help her by encouraging her to produce new works. She may have stayed in a supportive role, acting as inspiration and interpreter, but without her Schumann may never have finished his great works.

Clara seemed to enjoy domestic life after her marriage to Robert Schumann on 12th September 1840, despite the obstacles it created for her performing career and work as a composer. It did not help that Robert’s compositional activity took priority over hers. This meant that Clara was unable to compose herself, or even practice the piano. She wrote that

[m]y piano playing is falling behind. This always happens when Robert is composing. There is not even one little hour to be found in the whole day for myself! If only I don’t fall too far behind! Score reading has also been given up once again, but I hope it won’t be for long this time. (Sounds and Sweet Airs, 2016).

It was understood that Clara would make this sacrifice and Robert accepted it knowingly, acknowledging that “far too often she has to buy my songs at the price of invisibility and silence” (Kapralova Society Journal, 2009).

The main setback, however, seemed to be Clara Schumann herself. She echoed social values, writing that

I once believed that I had creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not wish to compose – there never was one able to do it. Am I intended to be the one? It would be arrogant to believe that. That was something with which my father tempted me in former days. But I soon gave up believing this. May Robert always create; that must always make me happy.

It gives us an insight into her beliefs about women and their capabilities. Robert did not entirely share these reservations about Clara and her creative ability. He had admired her music since they had first met and constantly encouraged her to produce new works – despite feeling that her “main occupation [was] as a mother”. Clara received encouraging words from others too. One contemporary believed her to have mastered the abstract strength needed to “attempt the more mature forms” of music. High praise indeed, and it was fortunate, perhaps, that Clara played the piano. The piano was considered by society as an acceptable instrument for a woman to play because the player remained seated, and therefore, more modest. The violin, on the other hand, was inappropriate due to the movements needed to play the instrument. Ironically, the violin is now considered a feminine instrument, and shows how these views have gradually changed over time.

It is by no means an understatement to say that Clara Schumann was an important figure in changing perceptions of women in music at the time. Many, including Felix Mendelssohn, were astounded at the musical works Clara produced. Mendelssohn even commented that “I would not believe that a woman could have composed something so sound and serious” in response to her Piano Trio Opus 17 (Sounds and Sweet Airs, 2016). To continue as a composer, though, was perhaps one battle too many for Clara. Instead, her focus remained on performance. It was no longer expected of performers to play their own compositions in concerts from 1850 and Clara Schumann embraced this change by establishing herself as an interpreter of music. After the death of Robert Schumann in 1856, she worked hard to promote his music and ensure her husband would be remembered. To the last, she was devoted to her husband and inspired by the music he created.

Clara Schumann used her drive, energy and sheer determination to overcome multiple obstacles in her lifetime. The result was a performing career that spanned approximately sixty-six years. She developed creative partnerships where one was always more important than the other, and she was constantly haunted by social values. Yet, despite all this, Clara Schumann achieved great things and became one of the greatest performers of her time. It seems sad that she has been forgotten, and only now, after decades of neglect, are her works finally starting to find their way into standard concert repertoires.

Sounds and Sweet Airs: the Forgotten Women of Classical Music, by Anna Beer (2016) is a particularly interesting read and is a recommended book to find out more about the composer.

-Claire Amundson

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.