How are girls represented in your favorite songs?

Have you ever thought about it?

Alternative Girls considers the impact that girls and women have had on current and past music scenes and the alternative ways of viewing themselves that their work has made possible. Looking beyond the front-woman of the music stage, we explore the work of women behind the scenes in the music industry in the male dominated roles of sound technicians, promoters, and CEOs. You will glimpse into the public and private worlds of the alternative music scene and the different ways of viewing our experiences as girls and women through one of the most powerful cultural products: music.

We highlight women from across the world for whom music is a passion and a career, from promoters to photographers, academics to sound technicians. While female artists have always provided female audiences new ways of thinking about their experiences and lives, much of the behind-the-scenes production remains dominated by men. As part of Alternative Girls, we brought together these different voices and experiences to provide a space for exploring what it means to be a girl or a woman in terms of making, appreciating, sharing and experiencing music.

We hope this exhibition introduces you to new musical heroines, from the stage and beyond.

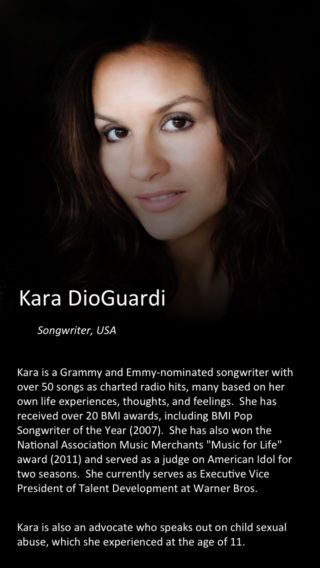

Meet the Alternative Girls

There are female singers and musicians in all genres, from hip-hop to classical. These women have inspired and continue to inspire girls across the world, many of them breaking out from the traditional expectations of girls to be quiet or well behaved, tidy or pretty in pink. They have re-imagined what it means to be a woman and shown what girls with a passion for music can achieve.

The histories of music have been written down and made into numerous films and television programmes, yet many of these either ignore female musicians or only offer one or two examples. Even the presenters seem to be all men!

To discover women who have changed the face of music, check out our podcast on Women in Music History (March 2017):

The Girls in the Boys Club

by Katie Rochow

Katie Rochow is a music enthusiast, globetrotter and curious ethnographer who has lived, worked and studied in Denmark, Sweden, Germany and New Zealand. She loves to read, think and write about music, people, cultures and places and is interested in visual research methods such as photography and map making.

Women in the Music Industry

What roles are available for women in the music industry? What is it like to work in a field dominated by men? This is a common experience for women across a range of jobs in the music industry. The reasons are complex, but gender stereotypes and expectations play a part in the comparatively lower number of female music industry professionals, particularly in the management or technical sectors.

This section has been supported by Sound Women a network that encourages and promotes women in UK radio. In the UK, over half of radio employees are women, but men still hold most presenter and management positions. Sound Women supports its members and aims to help women get more out of working in radio, and to help the radio industry get more out of women.

This section has been supported by Sound Women a network that encourages and promotes women in UK radio. In the UK, over half of radio employees are women, but men still hold most presenter and management positions. Sound Women supports its members and aims to help women get more out of working in radio, and to help the radio industry get more out of women.

Groups like as Sound Women are providing a supportive space for women in the music industry, and a network of people that encounter the same issues and want to change the industry. They work to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to develop their skills and move forward in their career, playing their part to highlight and address gender inequalities.

Alternative Girls: Interview with Ruth Barnes

Read on for an extra interview from our Alternative Girls series, with London-based radio presenter and podcast producer, Ruth Barnes.

Alternative Girls Interview: Capicua

Next in our Alternative Girls extras we have an interview with Portuguese hip-hop artist, Capicua, where she talks about her experience in the music industry.

Alternative Girls Interview: Tanyel Gumushan

Freelance music journalist Tanyel Gumushan reflects on her experience in the music industry and talks about her hopes for the future.

Musicians AND Mothers

It's no secret that the music industries, well, all creative industries really, rely pretty heavily on stereotypes. You'e got the whirlwind tornadoes with a rock n roll lifestyle not ready to be tamed, the ones considered crazy or weird, the angelic group of soppy...

Interview with a Music Journalist: Leonie Cooper

Leonie Cooper used to send reviews of every gig she attended to NME, until they published them. That was fourteen years ago, and now she's a senior staff writer at one of the UK's biggest new music magazines, online and in print. Some things are just meant to be. "I...

Experiences of a Music Journalist

It's the same almost every time. Hours before the show is about to start, I'm hanging around the stage door. The tour bus has verified that the artist is just behind the wall in front of me, and I'm in good company. Sometimes it's a couple of people, sometimes it's a...

Riot Grrrls

Tanyel Gumushan is our Take Over Blogger for Alternative Girl. A freelance music journalist based in the U.K., Tanyel takes a deep dive into the history of one of the most beloved alternative music movements: the Riot Grrrls.

Click on the following links to explore some of Tanyel’s writing:

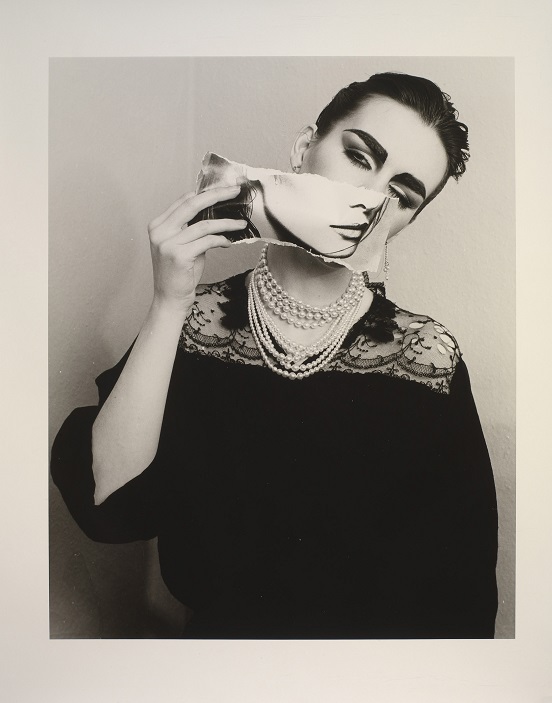

Photographing Women in Music

Making and enjoying music has been a vibrant and interesting subject for photographers and artists alike for many years and plays a large part in forming the ways we think about music history and culture. For example, image of the mohawk-wearing punk with a safety pin earring has become an icon of the Punk genre of music.. However, girls and women have long been invisible or sidelined as iconic representatives of the music that they love. This is especially true for ‘alternative’ music genres such as punk and rap.

Girls and women are often photographed as audience members, or listening to their music in their bedroom. Whilst these experiences are important to girls, they are often one aspect of how girls and women engage with music. Girls also form bands, they learn to play a range of instruments, they DJ with records, CDs and electronic music files, they show their musical passion through their clothes and their hair, through where they go and who they spend their time with.

Music is important to girls and they like to express this in a range of ways. Photographers Maggie Shannon from New York (USA) and Bethany Kane from Birmingham (England) share their work, documenting girls and women in music. Maggie’s ‘Noise Girls’ moves beyond the expectation of women to be fans, documenting a range of different women who make experimental music in New York. Bethany’s ‘Women in Subcultures’ make their mark in music scenes that are typically expected to be masculine, from punk to northern soul. Both Maggie and Bethany address the stereotypes of female music fandom.

This section was supported by the Youth Club archive. Youth Club is based in London and works to preserve, share, educate and celebrate youth culture history through a passionate network of photographers and creatives.

‘Noise Girls’

Maggie Shannon is a photographer based in New York. Through her 2015 ‘Noise Girls’ project, she captured the lives and passions of women in the city’s experimental music scene. The project was inspired by the frustrations of Maggie’s friend in the lack of media and photographic interest in female musicians within the scene (for more on this read David Rosenburg’s interview). Considered a masculine genre of music, Maggie was keen to show the role that female musicians played and to move beyond the expectations of women to be fans rather than the creators of the music. Each musician photographed was happy to provide Maggie with several more contacts, and the project grew and developed through these networks.

Here, Maggie talks about the ‘Noise Girls’ project and her experiences as a photographer. All images are the copyright and property of Maggie Shannon.

Your project, ‘Noise Girls’, focuses on women of the experimental music scene. How did this project develop?

My project Noise Girls started as a conversation between my good friend Megan Moncrief (who’s also featured in this project!) and I. We were sitting outside of a show she was hosting at her apartment, chatting and catching up. I was feeling a little lost at the time and trying to brainstorm a new project. A friend of ours, a fellow artist and musician, had recently dealt with some nasty sexist comments from a group of male musicians. We were both so angry at the situation and shocked at the lack of respect shown towards women in the music scene. A lightbulb went off then and I decided to do a portrait project documenting women in the noise scene in New York City, a way to celebrate how strong and talented they are.

Why do you think women in experimental music have been overlooked?

I think it’s a number of different things. One factor might be that they don’t feel welcome. The experimental music scene is dominated by white male musicians and those are the people that play and book the majority of shows. I’ve talked to a number of different musicians about this and when they’re putting together a show they usually go with people they know or have heard before, which is fair. Yet this practice doesn’t really leave it open to new people and isn’t inclusive to minorities. No one is taking risks or doing research.

I’ve heard all the arguments on this topic. That noise music just doesn’t draw women or that women should be more aggressive if they want to book more shows and get attention for their work. I really feel like these are all excuses and just an attempt to avoid a bigger problem. It’s a lot easier to just go with the flow and not push for change.

What do you hope to achieve through your photographs?

I hope to draw attention to the incredibly talented and diverse musicians that are living and working in the New York noise scene.

Why do you think that it is important to document women and their passions for music?

It seemed like an area that was lacking in documentation and I was eager to fill the void. I also think it’s important to keep track of the women pioneering in this scene.

What does music mean to you in both your role as a photographer and you personally?

Music was a way for me to find my place in New York City as an artist. The town where I went to college has an incredibly vibrant experimental music scene and I was drawn to this type of music in New York as well. It made this big scary city a little more familiar.

For me personally, music is so many things. It can really pick me up when I’m not feeling great and be a source of meditation and relaxation. On the other side of that, I run a lot faster when I’m listening to Taylor Swift at the gym! A lot of my friends are musicians and it’s so inspiring to hear the different ways they express themselves creatively, either through composing a jingle for a grocery store on the piano or coding something on a laptop. I guess listening to music makes me feel more creative!

‘Women in Subcultures’

by Bethany Kane

Bethany Kane is an independent photographer based in Birmingham, UK. Bethany aims to reveal aspects of identity, focusing on music scenes such as punk, skinhead, Oi! and northern soul. Her work has taken her all over the UK, but as she prefers to take photographs of people that she knows and who trust her to not misrepresent them, much of her work was created in the Midlands. For Bethany, the stereotypes and assumptions placed upon young people in subcultures, particularly punk and Oi!, has inspired her to represent the full diversity of experiences and the passion of these music fans, in particular as women in music scenes traditionally considered to be masculine. Bethany also contributes to the Youth Club archive, based in London.

Here, Bethany talks about photographing women in music scenes and her experiences as a photographer. All images are the copyright and property of Bethany Kane, unless otherwise stated.

Rebellion Festival 2016, Blackpool (UK)

How did you start photographing music subcultures?

I have always had a great interest in music since as long as I can remember. Aged 13, I started listening to Punk music and took a real interest in its sound, lyrics, attitude and style. I began to watch every documentary relating to the 70s Punk scene I could get my hands on and started to go to gigs on a regular basis. I started taking photos at gigs of bands and friends. Since then my interest in music scenes has grown and expanded and therefore my photographic subjects have too.

Birmingham Skinhead Meet Up, The Crown Pub, March 2013. Image used with the permission of Youth Club.

Why do you think that it is important to photograph girls in subcultures?

I was tired of people suggesting that women were introduced to music scenes through their male partners, when I knew from my own experience that this was too simplistic. From my teenage years, I have been fascinated in the Skinhead scene (both Ska/Reggae and Punk/Oi! influenced), but in England there didn’t seem to be many female scene members in comparison to male. More recently, I decided to photograph and interview women and to explore how they became a part of the scene and what attracts them to it. The most common reason for taking part is the sense of camaraderie and loyalty within the scene, with many people describing it as ‘one big family’.

Missy Baker for Brutus. Birmingham. 2015. Image used with the permission of Youth Club.

Punk and its DIY ethos encouraged me to express myself and to go out there and do it. By going to many skinhead events, I felt that I had developed a lot of knowledge and understanding that other photographers documenting the Punk and Skinhead scene hadn’t. For this reason I decided to cover it on behalf of a scene that I feel so passionate about.

Birmingham, December 2015.

Which female musicians have inspired you and why?

Poly Styrene and Kathleen Hanna. I feel they truly uniquely express themselves within the punk scene whilst making important comments on society that are still relevant in modern times. Kathleen Hanna encouraged women to believe in themselves and to speak out about topics they feel are so important through their individual creativity, through music, poetry, zine-making, art and photograph etc.

Stoke-on-Trent, October 2015.

I hope that women get the respect they deserve within the writing and documentation of subcultures. I hope to bring down the generalisation of women being only ‘scene participant girlfriends’ and instead emphasise their roles as important individuals who actively dedicate time to their scene, with opinions and views integral to its documentation.

Being Part of a Music Scene

The term ‘music scene’ is used to describe a community that brings together people who enjoy a particular type of music. Lots of people across the world are so passionate about music that they spend their weekends and evenings listening to it, dancing, talking to other people about it, and making their own music. Some people are dedicated to just one type of music, but others enjoy being part of several musical communities.

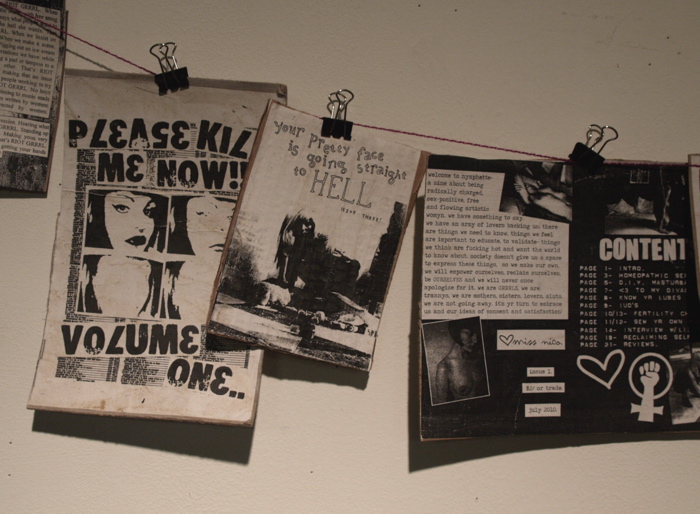

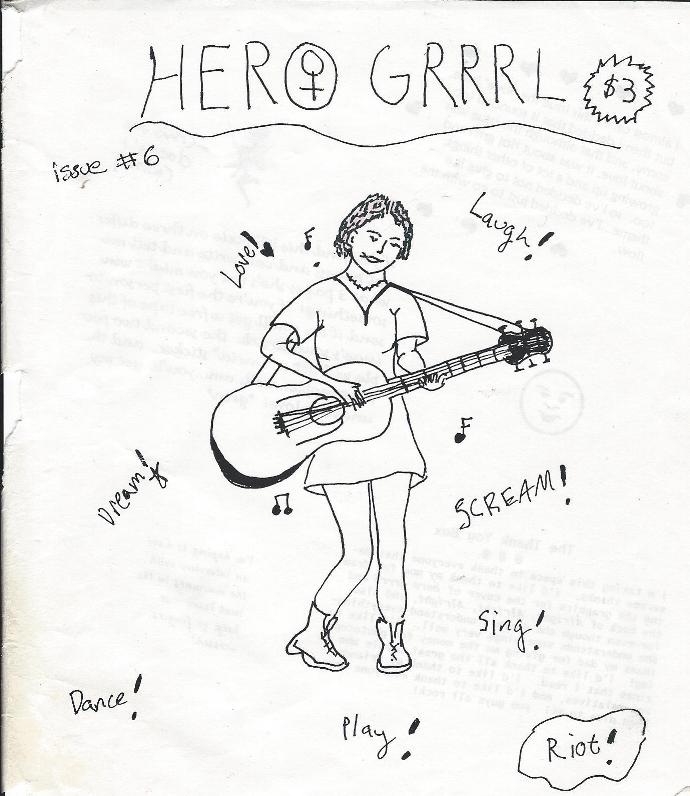

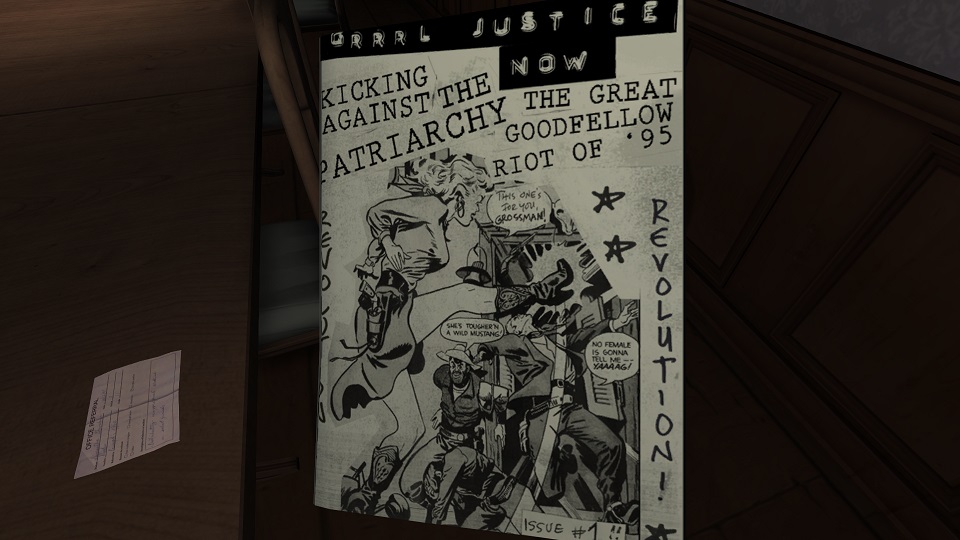

Of course, women and girls engage with different aspects of being in a music scene. For some music scenes, an ethos of ‘Do-It-Yourself’ (or DIY) is very important, and this is central to the production of home-made posters and ‘zines’. For others, collecting and playing records is a key part of being a member of a music scene, especially those that enjoy music from a time before CDs and the internet.

When we talk about music, it is also important to think about dancing, an action which requires us to listen to and engage with the music in a variety of physical ways. Members of different music scenes dance in different ways, in styles that have developed over many years and that seem to fit with the type of music. Certain dance styles that have become associated with male dancers, and sometimes this means that women are excluded from the activity. In this section, we celebrate girls in music scenes who made it their own and didn’t take no for an answer.

From Dada to Riot Grrrl: Women in Photomontage

by Bethany Kane, independent photographer and zine creator, Birmingham (UK)

Riot Grrrl zines used text and imagery to make a wider social comment on the expectations of women within society. Like Sterling’s work, the zines challenged beauty standards and how women are perceived in media whilst also commenting on female stereotypical societal roles. Like these artists, you too can make a comment on something that is important to you, whether it is something you love or something you hate. Try to express this by cutting and pasting images and text. Many artists have adopted photomontage as a technique to free their feelings. Through the use of images and/or text, they aim to comment on the current state of society. Hannah Hoch was the first pioneer of photomontage and part of the Berlin Dada movement who used art to demonstrate their anti-government feelings. She cut and pasted images together from popular magazines, illustrated journals and fashion publications, making links between them. Another influential female artist, Linder Sterling, used photomontage to challenge ideas surrounding the objectification of women and their role within society, placing images of flowers or household items next to the female body.

Alternative Girl contributor, Megan Sormus has put together a zine activity. Take a look at the Alternative Girl education guide for instructions on how to make your own grrrl zine!

Linder Sterling, ‘SheShe’ (1981) Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Creating Alternative Identities through the Grrrl Zine

By Megan Sormus, PhD student at the University of Northumbria

Riot Grrrl…. Is because we must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings…

Can you imagine a time without social media? Instagram is unheard of. The words ‘face’ and ‘book’ have not yet not been joined together to make the billion dollar corporation that Facebook is today, and “tweeting” is just something birds do. Welcome to the early 1990s. WhatsApp? What’s that? There’s not even such a thing as Snapchat. Want to complain, compliment, or create? Got a message to share to a mass audience? Back then, the quickest way to communicate was to telephone (via a clunky landline), by picking up a pen and writing, or through designing and photocopying hand-made posters, notices or fanzines (which will be the focus of this piece), and getting them out into the world by mail or spreading them by hand.

This may all sound rather unbelievable and in a few senses quite unattractive when looking back from the comfort of our present day, with its many modes of communication and its popular ways of sharing ideas, images, and music. But what I’m describing is not some alien world. While it may all seem pretty old school and opportunities may appear stifled, it was a time when individuals and, importantly for you readers of Alternative Girl, young women, used their creative input without the aid of mobile phones, the internet, computers and all of the other advanced technology existing at present that we all hold to our hearts and rely upon so heavily.

Despite this apparent ‘lack’, groups of young women used all opportunities of this era to their advantage. They became active cultural producers, as opposed to passive girl consumers. These young women felt a drive to create, a passion to protest, and to ultimately draw attention and form alliances based on the inadequacies and inequalities that they faced. With this, they built a self-sufficient community called Riot Grrrl, which then grew into allied networks all over America, as well as England (all done without the aid of Facebook!).

Along with music, a popular method riot grrrl used to spread their message was fanzines (or ‘zines’). Zines are small, self-published booklets that contain drawings, writings, photos (either original or appropriated from magazines) and covered either a single topic or a variety of topics. They can take the form of fan fiction made about a favourite band or celebrity, they can be personal like diaries, or contain examples of poetry and literary writing. Zines were originally part of the punk movement, and they reflected punks’ do-it-yourself spirit that was, in turn, copied by riot grrrls. Through the DIY creation of zines, paper cuts undoubtedly ensued, ink was spilled, and there was a guaranteed mess of cutting and pasting to create work that was (to say the least) rough around the edges. Forget posing with the very best filters available on Instagram. The aesthetics produced by riot grrrls were poor quality photocopied images that, in part, made up the crude and imprecise cut-and-paste collages of their zines.

To return to our present day, the question is: why would young women want to come back to these messy methods of creation? The answer lies in the fact that it is about maintaining that original grrrl spirit of seizing the tools available to become active girl agents. In our modern day, this can be strengthened by the technology that now lies at our fingertips. As noted by Mary Celeste Kearney, author of Girls Make Media, the creation of zines is vital as they ‘allow young females to develop other interests through their creative abilities, while also providing a space to explore their identity’.

With the growing interest and obsession with body image in the twenty- first century, zines, much like a visually noisy diary, give young women the opportunity to play with and try out alternative girl identities. To explore ‘alternative’ girl identities in this way means the zine acts as an empowering tool in the way that it reconstructs and reclaims mainstream images. To most girl consumers, these mainstream images of ‘perfect’ girls and the harmful goal to ‘be perfect’ is unrealistic and unattainable. Therefore, riot grrrl networks originally created zines that were specifically girl centred, called ‘grrrl zines’ by academic Mary Celeste Kearney:

The emphasis on femaleness is evident in the multiple female-specific discourses that appear in the pages of zines, including female bodies and health, female beauty standards and body image, female sexuality, female reproductive issues, violence against females […] and female representations in commercial popular culture.

Grrrl zines are a creative practice involving fantasy, facilitating girls’ explorations of different forms of identity, particularly those that subvert the established stories of girlhood.

– Mary Celeste Kearney, Girls Make Media

The riot grrrl community ran on a specific technology that cost nothing, and better still, was already inbuilt. This was their creative agency, and with this, the ability to make certain modes of production work for you and to, importantly, create your own meanings through following the ethos of DIY (do-it-yourself).

Does this sound impossible in our present day? No, it just needs a little more fine tuning. The most integral point of creating the space to ‘try’ out creative processes and practices, and for young women to explore identities is that they do not have to look, or be, perfect. Rather, creating alternative girl identities through the grrrl zine is about making a mess and presenting a clear clash of ideas. This makes the experiences and images of young women more realistic, and stands outside the restrictions of social media rules. So, next time you filter an image on Instagram, type a status on Facebook, or tweet your thoughts in 140 characters, remember to tune in to your inbuilt technology first, get old school, and be creative grrrl style.

Viewing Girl- / Woman-hood Through Music

Music is a powerful thing. It makes us feel a range of emotions, recall memories of people, places and events, it has the power to take us back in time and shoot us forward to the future. Music can also influence the ways in which we think about what it means to be a girl and the roles that women are expected to play in the world.

Music videos in particular have not always provided their audiences with positive role models, showing women to be sex objects or accessories for men, rather than intelligent and important individuals within their own right. Particularly for younger children, these limited and sexist ways of thinking about women can be highly influential and potentially damaging.

However, there are a range of inspirational musicians and singers who demonstrate that women are much more than a body. They are intelligent, passionate, creative, strong, and play their part in changing society for the better. The power that music holds means that we need these women at the helm to make sure that the messages it spreads are those of equality, solidarity and a celebration of diversity.

Here scholars who specialise in popular music consider the ways in which girls from across the world engage with music, and how music offers new and liberating ways to be a girl or a woman. Have a think about the sort of music that you listen to. How are women represented? Does this empower women or force them into certain roles?

Our February 2017 podcast, Girls and Bollywood, explored how women and girls are represented in Bollywood musicals. We also talked with girls who are part of the Indian diaspora, shedding light on how Bollywood influences real life girls and women. Click the player below to listen.

Alternative Girls: Body Positivity and Burlesque

Guest blogger Gemma Commane talks about the burlesque scene of the past and present, empowerment, and alternative femininity.

Alternative Girl: Finding alternative femininities in mainstream media

Researcher Hazel Collie talks about her own research, diving into females in mainstream media and how women and girls are portrayed.

Alternative Girls: Favorite pop artists in South Africa

Professor Sherine Van Wyk details her experiences asking a group of South African tween girls about their music likes and dislikes.

Alternative Girls: Negotiating girlhood, music and Islam in Indonesia

Cultural anthropologist Suzanne Naafs writes about navigating girlhood, Islam and music in Indonesia, and how music has influenced girlhood.

Alternative Girls

From the political activism of Billie Holiday during the Civil Rights Movement to Paradise Sorouri’s inspiration for aspiring Muslim artists, these ‘alternative girls’ have inspired us to rethink our capabilities and options as women, to reimagine what might be possible. They have pushed against the boundaries of what girls are expected to do in order to provide a way forward for the rest of us.

The work of these ‘alternative girls’, of musicians, music industry professionals, managers, producers, journalists, researchers, photographers, artists, and many others, continues to make a significant mark on the music that we love. They empower us and offer us the tools to be understand the power that music wields and the responsibilities we all hold in providing positive representations of women and girls.

As many different contributors have noted, the history of women in music has not always been part of the books that we read, the movies and TV shows that we watch, and the music that we hear on the radio. Through the work of people like Sarah Baker and many different groups, we are able to record and share the amazing work of women in music with future generations. As one of the main aims for Girl Museum, we are so proud to be able to do our part in recording and sharing all these ‘alternative girls’ with you.

Submit Your Story

Credits

- Claire Amundson (curator),

- Emily Chandler (podcast),

- Michelle O’Brien (curator),

- Hillary Hanel (education),

- Johannah Lord (education),

- Lauren Payton (curator)

- Sarah Raine (lead curator), and

- Tiffany Rhoades (supervising curator/podcast).

We would like to thank Sarah Baker, Ruth Barnes, Hazel Collie, Gemma Commane, Rana Emerson, Stephanie Fremaux, Tanyel Gumushan, Bethany Kane, Ana Matosfernandes, Suzanne Naafs, Katie Rochow, Maggie Shannon, Mazzy Snape, Megan Sormus, and Sherine van Wyk for their contributions to this exhibition.

Special thanks to all the academics, researchers, artists, girls and women in music who continue to forge ahead, making history and supporting each other. We hope that by introducing our viewers to new musical heroes and by sharing your experiences, we will inspire another generation of Alternative Girls.

Additional Resources

Television and Movies

- The Sapphires

- What Happened, Miss Simone?

- The Fits

- Janice Joplin

- Dreamgirls

- Flashdance

- Dirty Dancing

- Chicago

- The Get Down (Netflix series)

Photography Books

Academic research

- ‘It’s Not Only Rock and Roll: Popular Music in the Lives of Adolescents’ by Peter G. Christenson and Donald F. Roberts.

- ‘Just a Girl? Rock Music, Feminism, and the Cultural Construction of Female Youth’ by Gayle Wald.

- ‘Girl Groups, Girl Culture: Popular Music and Identity in the 1960s’ by Jacqueline Warwick

- ‘Growing up girls: Popular culture and the construction of identity’ by S R Mazzarella & N O Pecora (1999)

- ‘Pop in(to) the Bedroom: Popular Music in Pre-Teen Girls’ Bedroom Culture’ by Sarah Baker (2004)

- ‘Girls: Feminine Adolescence in Popular Culture and Cultural Theory’ by Catherine Driscoll (1999)

- ‘ “Where My Girls At?” Negotiating Black Womanhood in Music Videos’ by Rana Emerson (2002)

- ‘Representations of femininity in popular music’ by Nicola Dibben (1999)