What was life like for a girl in the Ancient World?

We’ve long been fascinated by ancient civilizations – like the Babylonians, Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, Indus Valley, and Maya. These civilizations flourished between 3000 BCE and 500 CE, and left behind monuments and mysteries that fascinate us today.

Yet evidence about young girls in these cultures has been scarce. In this exhibit, we bring to life Ancient Girls – showing how their daily lives were similar and different, both from each other and from our modern lives. Join us to travel back to these distant cultures, and discover the surprisingly complex lives that girls led. What you’ll find isn’t in any history book – and may leave you questioning everything you’ve been taught about ancient life.

Why Study Ancient Girls? Click to find out...

Many people first encounter ancient history in school, and it is typically the rote memorization of great civilizations, the ancient mysteries they left behind, and men’s contributions to science, art, philosophy, and so forth. What the history books neglect to mention is that girls – even young girls – played important roles in society. They led very complex lives.

By bringing these Ancient Girls back to life, we invite modern girls to look back on their ancient counterparts and wonder, “How am I like her? How am I different?” Girls also begin to critically reflect on the ways in which society then – and now – dictates what young girls should be. Finally, girls are able to find real life examples of incredible girls and women who, in ancient times, achieved awesome things.

The result? Girls are more engaged with history, because it relates directly to their own lives, and they are able to critically engage with societal expectations today. Girls also find female role models who will inspire them to fiercely pursue their dreams and challenge them to not accept societal norms at face value.

By proving that incredible girls have always existed, we create the incredible girls of tomorrow.

Download our Ancient Girls Education Guide to this exhibition or check out our Ancient Girls Coloring Pages (suitable for introducing younger students to objects from the ancient world or having fun). Plus, keep an eye out for additional activities located throughout the exhibit!

Mesopotamia

The cradle of civilization. Spanning what is now Iraq, Kuwait, parts of Syria, Turkey, and the Iran border, Sumeria, Assyria and Babylonia were the cultures of a region known as Mesopotamia. Beginning with large city-states that lined the river, these cultures flourished from the fourth millennium BCE until 485 BCE, making them some of the most enduring ancient civilizations. Their history is intertwined, as the strength of each waxed and waned for millennia.

What’s more, the status of girls in these cultures is far different from what you may have been led to believe.

What was life like for a girl in ancient Mesopotamia? Journey with us to discover the lives of girls during the Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian periods in the episode our GirlSpeak podcast featured below.

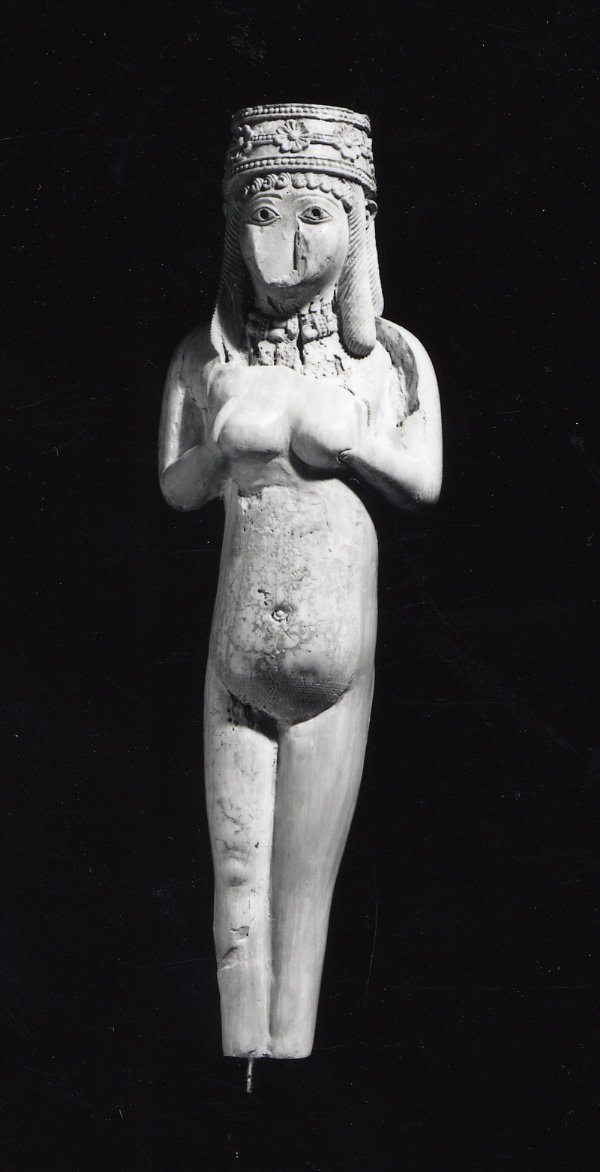

Nude figure of a woman made of ivory wearing an elaborate crown and necklace, with remains of blue inlay in the eyes, c. 8th to 7th century BCE, Toprakkale, Anatolia, Turkey. Held by The British Museum.

Indus Valley

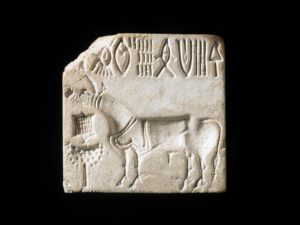

Vessel with two zebu, c. 2600-2350 BCE, Tarut Island. Currently held by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It reflects an “Intercultural Style” – or different styles of carving – that indicates the Indus Valley traded with and borrowed from other regions like Mesopotamia.

A Day in the Life: Aadrika, 13 years old, Harappa

Today is an exciting day because we are heading to Harappa to trade and meet with family. We come here every year, and I always look forward to the celebrations. I am very excited to wear my new clothes; this year, I have a colourful skirt and tunic top. My father has given me a beaded belt to wear. My mother says she will fix my hair for me after we have sold all our goods at the market. My father is a potter and makes wonderful creations.

In Harappa, we buy many things to last the year, and there are often exotic treasures to look at from all over the world. I love the hustle and bustle of the market, the smell of spices and perfumes in the air. You can get all sorts of things in Harappa, from silks and spices to jewels and ornaments. My father’s family lives in Harappa, but when he married my mother, they both moved to her village. All my mother’s sisters live nearby and my grandmother lives with us since my grandfather died. When we travel, I cannot take my dog with me and I will miss her very much. I have had her since she was a puppy and I love her very much!

We are a big family; I have four brothers and two sisters. It is a long journey to Harappa and can be quite boring, but in the evenings when we stop for the night, we have time to play games. My brother always brings his board games. As well as playing games, I also love to dance. Mother is teaching me a new dance and I cannot wait to show it all my aunts, uncles, and cousins when we arrive in Harappa.

Two of these settlements are the large cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. Here, Indus people worked as artisans who crafted luxury items or as farmers who herded cattle and cultivated huge crops of wheat, barley, legumes, and sesame. They used standardized bricks and weights, wells, drains, bathing platforms, and huge reservoirs. They also had thriving markets, extensive trade, and developed technologies to craft luxury goods.

Despite all we do know about the Indus Valley, many questions remain unanswered. But the objects they left behind may reveal the answers to some of our burning questions….

Necklace, 49.254-13, from the Indus Valley, Mohenjodaro, c. 2600-1900 BCE. Image courtesy National Museum – New Delhi. This necklace is made of steatite and gold beads capped with gold on both sides. It has pendants of jade and banded agate.

Indus Valley homes reveal a lot about girls’ lives. Made of mud brick, their houses were cool in summer and retained heat in winter. The houses had lots of rooms, including bathrooms with plumbing, situated around a central courtyard and topped with flat roofs. Girls probably had a lot of privacy and enjoyed sleeping on the roof during hot summer nights.

Girls also liked to dress up. Ceramic human representations from home sites are typically female and show us that girls wore a variety of hairstyles, ornaments, and clothing. They wore mini-dresses, necklaces, pendants, and neck-rings. Their clothes were made from cotton, flax, or silk cloth. Girls wore their hair in a number of ways, too: covered by turbans or elaborate headdresses, or piled high on top of their heads with flowers and ornaments worked in. Burials of young girls show that they loved to wear bangles on their arms or multiple strands of colored and patterned stones – and some archaeologists think these may have been a status symbol of some kind.

Because we’ve found so many ceramic figurines of girls, archaeologists think that the Indus Valley civilization may have practiced matrilocality, where married couples reside near the wife’s parents and together form large clan-like families centered around the female line. This is backed by genetic studies conducted on their remains, which show that women in Indus Valley cities had much stronger genetic links than men.

Seals with writing found at Mohenjo-Daro. Courtesy BBC.

Did Indus Valley people have schools? We’re not sure.

Some archaeologists believe that children did go to school to learn reading, writing, and religion. We know that there had to be some system of education, because the Indus Valley system of writing is complex. Indus people also used standardized systems of weights and measures, which tells us that they had to have some way of learning how to use those systems.

The Indus also made a lot of seals. Starting around 2800 BCE in Harappa, merchants used a variety of seals to indicate ownership of storerooms or goods. Like the one shown here, these seals were made from clay and attached to an object by a chord or secured onto a door. Some of these seals show females participating in rituals, such as the consecration of Priestesses in front of a mythological figure known as the Lady of the Beasts. We’re not sure whether these seals were used by girls, but the presence of females on them suggests that some women – including priestesses – might have been merchants or participated in business transactions.

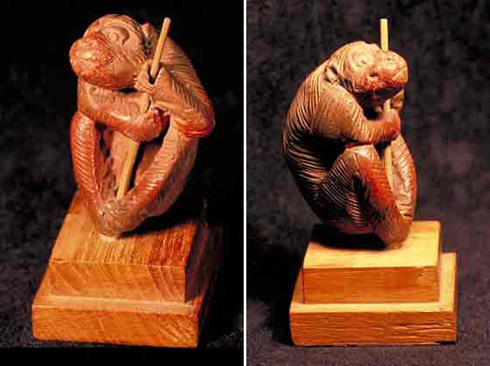

“Indus Valley Climbing Monkey Toy [Object],” c. 2500 BCE, Mohenjo-Daro, in Children and Youth in History, Item #312, Annotated by Susan Douglass.

Dog figurine with collar from Harappa. Image courtesy Harappa.com. This likely indicates that girls kept dogs as pets.

Girls also had pets. We’ve found many preserved animal paw prints that indicate families would have kept monkeys, birds, lizards, snakes, deer, pigs, lambs, and dogs as pets. There are also figurines made of these animals, suggesting that pets were a central part of family life.

Dancing Girl, c. 2500 BCE from Mohenjodaro. Image courtesy National Museum – New Delhi.

Another thing that girls enjoyed was dance. We’re not sure if this was just play or was tied to a ritual, but there are many Indus Valley figurines of girls dancing. It’s also possible that these dancing figures might be slaves – like other civilizations that had dancing slave girls, the girl shown here is naked except for her necklaces and bangles.

Photo of the Great Bath under excavation at Mohenjo-Daro. Courtesy Saqib Qayyum, 2014.

We’re not sure what religion the Indus Valley practiced. Archaeologists have found a variety of figurines and images that suggest they had a religion, but to date there is little evidence of temples. The only religious site we know of is a shrine at Mohenjo-Daro that is part of the Great Bath complex, where people took part in ritual bathing. This shrine features a sculptured female head, several pieces of stone sculptures, miniature pots and figures, and a large number of seals with a unicorn motif.

“Intaglio seal (H97-3433/7617-01) with script and unicorn motif found in Trench 41NE in 1997. This seal dates to approximately 2200 BCE, at the transition between Harappa Periods 3B and 3C.” British Museum

It’s this unicorn motif that is the most suggestive of religion. The earliest representation of a unicorn dates back to 2600 BCE, and unicorns were used for over 700 years. The unicorn images can vary regionally, but are most often found on stamp seals and on tablets, suggesting it was very important throughout the Indus Valley.

Woman with tigers on an Indus seal. “The Woman Who Dances with Tigers: Indus Valley Seals” from SuppressedHistories.net.

Other representations suggest that horned beings were part of religion. Many horned human figures and ritual designs are widespread, especially one of a seated male in a yoga-like position. Women are also depicted wearing this horned headdress, sometimes fighting a tiger. One is known as the Lady of the Beasts, though images of her are rare. She is often seen seated on a throne, wearing a buffalo horned headdress and surrounded by numerous animals.

Looking at all of this evidence, it’s possible that girls were part of religion – as priestesses or worshipping the Lady of the Beasts. They likely took part in ritual bathing – which is still practiced today in India. Girls may also have constructed or worshipped shrines. Today, villages in India have humble shrines that look like domestic huts and temples are rare. It’s likely that Indus Valley girls worshipped within their own homes rather than at temples, using these modest shrines to revere the gods with offerings of fruit and flowers after partaking in a ritual bath.

Curator's Note

Draupadi

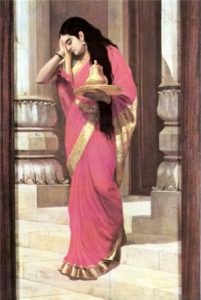

Draupadi by Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), date unknown.

Draupadi is a main character in the Mahabharata, a Hindu epic. The wife of the five Pandavas, she is a powerful and fiery queen.

One of the passages of the Mahabharata that shows Draupadi’s strength is the game of dice. Duryodhana, a rival king, has conspired to win the kingdom of the Pandavas. He challenges the brothers to a game of dice, ensuring his own victory by using a pair of enchanted dice. Yudhishthira bets everything the brothers have – including Draupadi – and loses.

When Draupadi discovers she is Duryodhana’s slave, she is furious. She refuses to appear in court, arguing that Yudhishthira had no right to use her as a bet. Duryhodhana orders Draupadi to be dragged to court, where he commands that she be disrobed. Seeing that her husbands will do nothing to protect her, Draupadi calls upon Krishna to protect her. The god obeys: no matter how much of her sari is unfurled, more layers appear. Eventually, her attackers give up due to exhaustion.

Draupadi proceeds to verbally attack the whole court, cursing everyone present. Fearing retribution, Duryodhana’s mother Gandhari intervenes, granting Draupadi three wishes. Draupadi uses these to recover her husbands’ freedom, wealth, and powers.

Gargi

Gargi embroidery by Rebel Women Embroidery, 2015.

Gargi Vachaknavi was an ancient Indian philosopher credited with writing many hymns of the Rig Veda. She never married, choosing instead to study the Brahmavidya all her life. She was known for her intellect and extensive knowledge of the Vedas and Upanishads, and frequently bested her male peers in debates.

In one debate, Gargi went up against the sage Yajnavalkya. King Janaka of Videha had organised a Rajasuya Yagna, inviting the greatest men and women of the age: sages, kings, princes and princesses. Janaka, impressed with the number of scholars present, decided to hold a brahmayajna – a philosophical debate, to honour the sage with the greatest knowledge of the Brahmas.

Yajnavalkya, thinking himself to be the most spiritual of all the sages there, ordered his disciple to remove the prize to his house before the debate had even begun. This infuriated many of the scholars present. Yet few were willing to debate with him, unsure of their own knowledge. Gargi was one of the eight scholars who challenged him – and the only woman.

One by one, each of the scholars was defeated by Yajnavalkya, until only Gargi remained. She held repeated arguments against him, questioning his superiority among the scholars. The debate focused on the very nature of reality, from the metaphysical to the natural world. Although Gargi eventually conceded to Yajnavalkya, her debate lasted the longest of all the scholars, proving her capabilities.

Indus Girls

Though much of the Indus Valley civilization remains a mystery, it’s clear that girls were important to society. They used clothing and jewelry extensively, perhaps to indicate their social status, and lived in family groups that were matrilineal. Girls may have learned reading and writing, even becoming merchants who used seals. They also participated in religion – partaking in ritual baths and using small shrines to worship a variety of deities, including the unicorn and the Lady of the Beasts. Though we’ve found very few burials, the ones we have of girls indicate that they were buried with some of their wealth, including jewelry and pottery.

Overall, this tells us that girls were respected by Indus Valley society. It’s even possible that the Indus Valley women had equal rights to men. We won’t know for sure until we find more evidence.

Minoan and Mycenaean

Finger-ring, Mycenaean, c. 1400-1100 BCE. Excavated in Rhodes, and now held by The British Museum.

A Day in the Life: Kalliope, age 10

Today has been such a busy day. Now that I am ten years old, mother expects me to learn even more about running the household. My favourite thing is cooking. I love being in the kitchen with all its sights and smells and creating tasty dishes for my family to enjoy. I don’t like helping with the weaving. I am not old enough to use the loom yet, and its colours and intricacies fascinate me. But I am only trusted with carding the wool and spinning the thread with my younger sisters. My older sister, Leda, is allowed to weave with mother. Together they make the most wonderful cloth. It was my mother’s skill with weaving that ensured her marriage to my father, even though she did not have a large dowry. I hope that I have as much talent as mother when I am allowed to weave. Leda is good at weaving but mother is still better.

Leda will soon be old enough to be married and is excited at the prospect of having a household of her own. Papa will arrange it and I know she hopes her future husband will be handsome. When she has her children I will be allowed to stay with her to help out. I pray that she has many children, like mother, and brings honour to her family.

When I have time to myself, I like to play with my doll. Mother gave it to me for my last birthday and I love her very much! I call her Aminta. I also like to play with my brothers and sisters, although my brothers soon get tired of playing with me. I don’t go to school because I learn everything I need to at home with mother and my aunts. My future husband will need me to run the household and bear the children, not read or write. Mother will arrange for me to learn to play an instrument, I am not sure which yet, but I know I have a nice singing voice. I am excited to start my lessons.

After the fall of these civilizations, Greece entered a Dark Age (1100-800 BCE), reemerging with the rise of patriarchal city-states such as Athens and Thebes. These new city-states made women’s role restrictively more domestic through the 5th Century BCE. Girls in ancient Greece, or κορίτσια (koritsia), although largely overlooked, served very specific and vital roles in these societies. This section of the exhibit will examine the role that Greek women and girls played in their homes and communities, specifically in these Prehistoric and Pre-Classical eras.

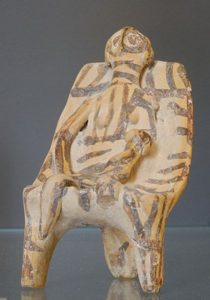

Phi-figure of a woman holding a child. These types of statues are known as Kourotrophe as they depict child-rearing (Mycenae, 1360 BCE). Museé du Louvre, via Wikimedia Commons.

For young girls in ancient Greece, family and the household, or οἶκος (oikos), would have been the focus of everyday life. The most important role for a girl was to be groomed to become a wife and a mother. From a very young age, she learned how to cook, clean, and weave. Girls were expected to pitch in with household work or any family businesses, and above all else, obey their father. The father was the head of the household and technical owner of any of his children.

When a daughter reached puberty, her father would arrange a marriage for her without her or the mother’s consent. The father would then exchange a dowry (property or money given by a bride to her husband) for bridewealth (property or money brought by a husband to his wife’s family). Most dowries included acreage of land or portions of wealth to be paid to the husband’s family. Bridewealth was negotiated on the perceived worth of the bride, whether she be beautiful, fertile, or industrious, and given as a proof to the bride’s family that their daughter will be well taken care of in this new family. Since girls cannot inherit any property, this ensured the daughter’s economic value to the family would be maintained.

Wealthy girls were often forbidden from leaving their houses, except for religious ceremonies or to visit other women. Any time girls left the house, they had to have their slaves come as chaperones. Poorer families who could not afford slaves required girls to leave the house more often to work in fields or to fetch water. Usually, this confinement was to ensure the paternity of a woman’s children. Every child was the property of the husband and, therefore, his financial responsibility.

New wives were expected to have children right away to try for as many children as possible. Childbearing and rearing was much more revered in the Prehistoric Greek civilizations than in the later Greek city-states. Fertility is the most common motif of statuary for the civilizations of the Cycladic islands, while raising children among groups of women is iconic of figurines from Mycenae. This tells us that a girl’s value was primarily as a wife and mother.

An epinetron is a sheath for one’s leg that would protect it during the weaving process. This Epinetron depicts four women weaving and spinning (500-480 BCE). British Museum

Unlike boys, girls in ancient Greece did not go to school for a formal education. At the age of 6, when most boys would go to get an education, or παιδεία (paideia), girls would stay home with their mothers and learn domestic trades. Along with cooking and cleaning, girls were taught how to weave, spin thread, and contribute to textile production.

Textile production was one of the most profitable skills a woman or girl could have in the ancient world. Even as a slave, if a girl had incredible skills she could be sold to work for wealthier families or even to the ruling families of the region. In cities like Pylos and Knossos, slave girls traded as weavers to the cities’ palaces were recorded on Linear B tablets and stored in the palace archives. Having any written record shows the importance of the transaction and places value on the skills and products the girls were providing. Textiles were one of Mycenae’s largest exports, putting skilled weavers in high demand. It was only in Sparta where girls were not expected to be highly skilled at weaving and spinning thread, because physical fitness in women was thought to provide the society with stronger sons and therefore soldiers.

Depending on her family’s social and economic standing, a girl would be taught practical skills like how to plough fields and tend to animals, or even how to play an instrument or read and write. Women of wealth and high social standing such as Sappho and Telesilla of Argos are some of the girls who received an education and went on to create poetry in an all-male dominated society.

Sculptural depiction of a young Minoan girl on a swing (Aghia Triada, 1450-1300 BCE). Archaeological Museum of Heraklion, via Wikimedia Commons.

While there have been many artifacts recovered of toys and games, there is no way to prove that young girls would have played with them. Pre-Classical artistic representations of young girls more often show them as a part of a religious ritual or representing the industriousness of women weaving. They are rarely shown at play. It would be nice to think that girls got the same amount of time to play as the young boys, but girls were confined to the home to tend to domestic duties, usually from a very young age. However, during their infancy, since they would be watched by groups of women, boys and girls would have been allowed to play together.

Toys like ceramic rattles, spinning tops, and throwing discs would have been the most common. Wealthier families could afford more elaborate dolls and figures as well as time to play, while poorer families had to employ their children to work out in the fields or to help with caring for the household.

Bronze statue of a female Spartan athlete competing in the Heraean Games (Prizren Serbia , 520-500 BCE). British Museum, via Wikimedia Commons.

In most of Greece, girls were excluded from being able to train and exercise outdoors where men were, and were forbidden from participating in athletic competitions such as the Olympic Games. But in places like Sparta, it was thought that all Spartans should be well trained and physically fit, including the women. This was to help create stronger soldiers by starting with stronger mothers. Sparta’s beliefs were frowned upon by the other Greek city-states, who thought men were stronger when separated from women.

Why was Sparta so different from other Greek city-states? Watch this TED-Ed video for the answer.

A young shaved head girl lays crocus stamens at the feet of a large seated goddess flanked by a griffin, known as the Mistress of Animals (Akrotiri, 1650 BCE). Museum of Prehistoric Thira, via Wikimedia Commons.

Greek religion and mythology begins to take shape during this Pre-Classical era, starting first as a humble theology focused around nature and a mother goddess. Girls held a very high status during this time, especially in the Minoan civilization, as they were seen as mothers and life bringers. Their religion spread around the Aegean by trade and commerce, throughout the Cycladic islands and to the more patriarchal Mycenaeans in the Peloponnese. In all these regions, girls remained the dominant figures in the religion, whether as deities or priestesses.

In a fresco known as the saffron gatherers, a young girl with a shaven head is seen picking crocuses with another woman priestess. Seen as a ritual of initiation, the crocus stamens were used to dye women’s ceremonial robes a golden color (Akrotiri, 1600 BCE). Museum of Prehistoric Thira, via Wikimedia Commons.

While not much is known about the specifics of the Minoan religion, many of the artistic and figural representations left behind show an intricate initiation process for young girls into priestess-hood and the many rites, or τέλος (telos), performed as a priestess. Young girls would shave but a few tendrils of hair from their heads and gather crocuses to dye their ceremonial robes a yellow color. This same flower is also associated with relieving menstrual cramping. They would also use the crocuses as incense and offerings to the goddess. Priestesses would oversee ceremonial processions, leave offerings at the peak sanctuaries, and conduct animal sacrifices.

After the fall of the Mycenaean civilization in 1100 BCE, the Dark Ages ushered in a refining of the Greek theology influenced more by the patriarchal societies of the East. The division between priestesses and average girls that once was on equal planes was now very far apart. While girls still played a vital role in rituals, they did not hold the same positions in religion that they once had, losing the privileges that came with power and influence.

Eritha of Pylos

In the Mycenaean era, priestesses were incredibly powerful, controlling land, textiles, servants, and even bronze – an incredibly important resource at that time. Once priestess was Eritha of Pylos, known to us from the Linear B tablets that document daily life in the Mycenaean world.

Eritha was priestess of the sanctuary of the goddess Potnia, on Pylos. She was a very powerful figure, challenging the local council over the status of land held by the sanctuary. Eritha probably appeared to the council on behalf of Potnia; nevertheless, the fact that she is named in the court documentation demonstrates her elevated status, compared to her lay peers.

Fresco depicting a goddess or priestess in Mycenae, 1250-1180 BC. Image courtesy Wikimedia public domain.

On Pylos, there were five official cult titles for women: Priestess, Keybearer, Servant of the God, Servant of the Priestess, or Servant of the Keybearer. Like Eritha, these women are the only women named and titled throughout the Linear B texts. As priestesses, girls were able to navigate the limitations of society. Eritha’s ability to challenge the local council indicates that she is at the top of the pile. However, the privileges enjoyed by the other female religious officials – such as control over certain resources – raised them above many women of their time.

Helen of Troy

Helen of Troy, as depicted by the Menelaus Painter. In this scene, Menelaus intends to strike Helen; struck by her beauty, he drops his sword. A flying Eros and Aphrodite (on the left) watch the scene. This object was found in Gnathia (now Egnazia, Italy), and dates to around 450-440 BCE. Currently held by the Louvre, and under public domain via Wikimedia.

The legend of Helen of Troy has fascinated poets, writers, and artists for centuries. Famed for her beauty, popular portrayals show her as either a victim of kidnapping or a fickle wife who caused the Trojan war by running away and eloping with Prince Paris of Troy. This narrative has been handed down to us from the Iliad, the earliest literary representation of Helen.

Yet evidence from the Mycenaean and Minoan eras suggests that Helen was worshipped as a goddess. Although some shrines to Helen may be considered hero-worship, Isocrates notes that at Therapne, Helen was venerated as a goddess. Likewise, on the island of Rhodes, Helen was called Helen Dendritis. Translating as ‘Helen of the Trees,’ this suggests that she was known to the Minoans as a fertility goddess. The shrine at Therapne is today known as the ‘Menelaion’ – yet the evidence suggests that Helen was the principal focus of worship. Menelaus was only added later, once Helen of Therapne became associated with the myth of Helen of Troy. Even then, Menelaus is honored as ‘her husband’ rather than Helen being venerated as ‘his wife.’

Later traditions have focus on the passive role of Helen as a wife, victim, or culprit. While today we know her as a mythological heroine, for the Minoans and Mycenaeans, she was a goddess and a powerful figure who was worshipped in her own right.

Greek Girls

Starting as life bringers, equal to that of the mother goddess and goddess of nature, to being confined to positions of motherhood and household production, the role of women and girls went through tumultuous changes in Pre-Classical Greek societies. Though the visible mark of women and girls in this era of Greek history diminished, they remained the constant backbones to religion, family, and economic life. As textile manufacturers, child-rearers, and midwives, the contributions of Ancient Greek girls helped to make Greece one of the greatest civilizations in human history. Life was not necessarily an easy one for these girls, but from the art and poetry they left behind, we know that play, love, and family were as important to life then as they are today.

While archaeologists and anthropologists have been studying these Pre-Classical Greek societies for a couple hundred years now, not much attention has been paid to the evidence left behind (or lack thereof) of women and girls. As feminist historians reinterpret sites and evidence left behind, new facts may be brought to light about their true impact on the building of these cultures.

Presentations of Girlhood and Womanhood in Ancient Minoan Frescoes

by Izzie Heis (May 2021)

Generally, the theme of girlhood in ancient Greek art is… well…. somewhat non-existent. Save from the odd vase painting of Iphigenia (a young girl sacrificed to the gods by her father… Great!), the general view of femininity we are granted in Greek art is mythic queens, powerful goddesses, and rich women, immortalised by their husbands in the form of grave steles. In short, we are not granted anything that resembles ourselves, or our own experience of girlhood or womanhood.

However, thousands of years before the classical Greeks that we traditionally think of, there were the Minoans: the Minoans existed over a thousand years before the Classical Greeks, roughly between 3650-1400BCE. Relatively little is known about Minoan society in comparison to their classical counterparts, especially in regards to myth and religion: whereas with Classical Greeks there are hundreds of named figures, such as Zeus, Athena, etc. we simply do not have this same level of knowledge in regards to Minoan mythical figures. One of our greatest clues as to Minoan culture is indicated in the surviving examples of art that we have, such as vases, sculptures, and the focus of this blog: frescoes.

Frescoes are paintings done on walls or ceilings of buildings, in a manner that allows the paint to dry into the plaster of the wall itself. There are several surviving frescoes from the Minoan period recovered from buildings and houses. They are extremely striking due to their use of bright primary colours, ethereal vegetation, and occasionally vibrant mythical creatures. Al the frescoes I am discussing in this post were found in Akrotiri, a small village in Santorini.

What strikes me about Minoan frescoes, however, is the presentation of girls and women. Not only are they present, but they are often depicted as constructive members of society, free from the male gaze, rather than forlornly clinging to the sides of their mothers. What’s more, they are seen as having active roles as opposed to passively existing under masculine desire and ownership.

For example, this fresco, The Saffron Gatherers (otherwise known as The Crocus Gatherers), depicts a young girl (right), alongside a slightly older girl/young woman (left). As you might have gathered from this fresco’s rather explanatory title, these two figures are depicted as collecting the spice saffron from crocus flowers. Not only does this fresco depict girls as being active and productive, but, what’s more, they are performing a task that requires skill, and a large degree of trust and importance. The process of collecting saffron from crocus flowers is infamously an extremely delicate and difficult process, which still to this day is performed by hand. The intricacy of this laborious process means even to this day, saffron is worth more than its weight in gold!

Whereas women in art throughout history are often presented in stagnant and unmoving positions (as if to be taken in by the viewer) both of the girls in this fresco are presented in active and ‘unfeminine’ positions, where their bodies are not painted to be at their most flattering angle, with the girl on the right actively leaning her body away from the viewer. Additionally, both of these girls are fully clothed with realistic body types, engaging in joyful conversation as they work. Seeing young girls being depicted with such vibrancy is beyond refreshing.

The fresco on the adjoining wall to where The Saffron Gatherers was found also gives the task of gathering saffron the implication of religious importance. This fresco has been referred to by archaeologists as The Mistress of Animals, or else The Saffron Goddess. On the left hand side, a young girl, just like the one depicted in The Saffron Gatherers appears to be depositing a basket of saffron into a pile. She looks eagerly towards the figure at the far right of the fresco, a tall and beautiful woman sitting on a pile of cushions, with a mythical bird-like creature to her right. A monkey-like figure is offering something to the seated woman.

Upon viewing this fresco, it is immediately noticeable that all the figures are turned towards the seated woman, thus making her immediately noticeable to the viewer, too. Upon further inspection, we can see that, although the figure is seated, she would be inhumanly tall in comparison to the girl and monkey figure if she were to stand up. It is because of this height and this implied importance that ancient historians believe this figure to be a goddess, hence the alternate title of this fresco of The Saffron Goddess.

Not only is this tall, beautiful, and powerful being a wonderful example of female representation, but it is equally empowering to see the young girl depicted as part of this scene. It is so rare in modern art that we see young girls playing important and meaningful roles, yet here we see this girl not only acting in a religious ritual, but being important enough to be entrusted in the presence of a goddess. Her bright other-worldly clothing and eager smile truly make her a captivating and inspiring presentation of girlhood.

These are just two of many Minoan frescoes depicting girls and young women in a beautiful, inspiring, or meaningful light. I believe these frescoes in particular are the kind of art that every young girl should see, and use to admire their brightly-coloured historical counterparts. Attached below is a list of links to other Minoan frescoes depicting young girls or women in an interesting, productive, or empowering light. I definitely encourage any reader to delve further into the frescoes uncovered throughout Greece, and, thus, the world of this culture’s beautiful artwork.

Egypt

Mummy of a girl (7 years, +/- 3 years), named Tjayasetimu.The mummy is enclosed in a cartonnage case in the shape of an adult woman. 26th Dynasty, circa 900 BCE, Thebes. Held by The British Museum.

The hieroglyphic text in the centre of the case reads:

‘An offering which the king gives to Osiris-Sokar who resides in his shetayet-shrine, the great god, the lord of heaven, the ruler of eternity in Heliopolis, in order that he might give water to the ba, offerings to the corpse and clothing to the mummy of the One who is Praised in the Interior of Amun Tjayasetimu, daughter of Pakharu, justified.’

A Day in the Life: Isetnofret, age 12, Thebes

It is currently summertime and the sun scorches down upon the desert landscape and makes us all very hot. We sleep on the roof at night because it is cooler outside than in our home. My father is a weaver and my mother takes care of the household and sells the goods in the market. I have four brothers and three sisters.

As the oldest girl, it is my responsibility to help my mother around the house. She taught me how to cook, and now I help in the kitchen baking the bread and making meals. I also help with the weaving. I am almost as good as my mother and father and my cloth makes the family money. I am very proud of the work my family does and my place in helping. Father lets me keep part of the money my cloth makes. I am saving it up for when I am married.

I look after the younger children during the day and we have a lot of fun playing with our toys and dolls. Today we are going swimming and I cannot wait to cool off in the water. It is so hot that it makes me sweat and I am glad of my cool linen dress and short hair.

We are busy at the moment with preparations for my cousin’s wedding. Soon, I will become a woman and get married too, and have a family of my own. I will wear a wig and makeup like my mother at the wedding. I have been watching her closely, hoping to copy her graceful movements. I will go the temple of Hathor to pray for this tomorrow and then pray for my cousin for a happy marriage and a baby. I am very excited for what is to come!

In contrast, Tjayasetimu was a 7-year-old singer in the temple choir for the god Amun, titled “singer of the interior,” who died at the age of seven or so, probably of a disease like cholera. She was elaborately mummified and buried in a coffin too big for her, though no one knows why. Robbed from the grave, scientists believe she may have been from Karnak near Thebes, and probably played a sistrum, harp, or bone clappers in addition to singing.

Egyptian civilization is known for its wondrous pyramids, irrigation systems, highly organized society, and mythology. There is also a lot of evidence that suggests Egyptian girls held important roles in society and their families.

A History of Egyptology by Alex Leigh

Ancient Egyptians reinterpreted their own culture over the course of its long history. But Egypt first entered Western popular imagination through Greek and Roman interpretations. In the 5th century BC, the historian Herodotus wrote a famous account of Egypt that described unusual customs and fantastical creatures. Written by a Greek author and designed for a Greek audience, it reflects the Greek perception of Ancient Egypt, rather than Ancient Egypt itself.

The Romans, too, reinterpreted Ancient Egypt, which became part of the Roman Empire in 40 BC with the capture of Cleopatra. Scenes depicting the Nile were popular in Roman houses and certain architectural styles were modelled on Egyptian buildings. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Canopeum at Hadrian’s villa in Tivoli, so called because it is said to copy the water-channel that connected the city of Canopus to Alexandria.

The canopus at Hadrian’s villa. Image courtesy Archaeology Travel.

Hadrian had a long-standing fascination with Egypt. Between 128 and 130 CE, he toured Egypt with the imperial court, and he had the court poet, Julia Balbilla, compose several epigrams to celebrate the visit. Julia was a Roman noble woman and served as lady in waiting to Hadrian’s wife, Vibia Sabina. Four of her epigrams survive, as they were inscribed on one of the Colossi of Memnon, two huge statues in the city of Thebes in Egypt. The first epigram, below, tells the story of the pharaoh Memnon, whose colossi partially collapsed in 27 BC. Following its collapse, the remaining lower half was reputed to “sing” a sound similar to the striking of brass or whistling, as Julia describes:

Memnon the Egyptian I learnt, when warned by the rays of the sun,

speaks from Theban stone.

When he saw Hadrian, the king of all, before rays of the sun,

he greeted him – as far as he was able.

But when the Titan driving through the heavens with his steeds of white,

brought into shadow the second measure of hours,

like ringing bronze Memnon again sent out his voice.

Sharp-toned, he sent out his greeting and for a third time a mighty roar.

The emperor Hadrian then himself bid welcome to

Memnon and left on stone for generations to come.

This inscription recounting all that he saw and all that he heard.

It was clear to all that the gods love him.

During the trip, Hadrian’s young lover Antinous drowned in the Nile. Some of the many statues that Hadrian had made to remember Antinous combine Egyptian and Roman styles of art.

Antinous as the Egyptian god Osiris, originally discovered in 1738-9 in Hadrian’s Villa. From the Vatican Museum collection, Museo Gregoriano Egizio 22795. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

These Greek and Roman interpretations of Egypt, as outside views, do not present an accurate reflection of Ancient Egypt. Nonetheless, they entered the Western view of Egypt, influencing ideas in further centuries. The earliest scholars of Egyptology, in the 18th century, would have received a ‘Classical’ education, based on studying Greek and Roman texts. Therefore, their ideas were influenced by these views, and rooted Egyptology in a Eurocentric model.

The study of Ancient Egypt became popular following Napolean’s attempted invasion of Egypt in 1798-1801, as it resulted in the publication of the Description de l’Egypte, giving easy access to depictions of Ancient Egyptian art to Europeans for the first time. Following this, in the 19th century artistic movements such as Romanticism renewed interest in Ancient Egypt. Percy Bysshe Shelley captured the Colossi of Memnon (the same statutes that Hadrian visited) in the poem Ozymandius. Paintings – such as this one by John William Waterhouse, which depicts Cleopatra – created a popular view of Ancient Egypt. At the same time, cheaper travel meant that increased numbers of amateur archaeologists could visit Egypt and participate in excavations.

Cleopatra by John William Waterhouse, 1888. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Egyptology as a discipline has been criticised for focusing on a European view of Ancient Egypt. This viewpoint has led to a number of controversies, such as the debate over whether Ancient Egyptians were black. Understanding the history of Egyptology helps to uncover why these biases have emerged, and to promote different ways of representing Ancient Egyptian history. Recently, some scholars have begun to support Afro-Centric study of Ancient Egypt, which places Ancient Egypt within an African context. The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has a ‘Virtual Kemet’ exhibition, which takes its name from the Ancient Egyptian word for Egypt, ‘kmt’, meaning ‘the black land’ or ‘land of the black people’.

The study of Ancient Egypt has historically been focused on a European viewpoint. This has led to a number of biases, and has affected both Egyptology and the popular view of Ancient Egypt. However, by widening its view to include other opinions, Egyptology is moving towards a more complete understanding of Ancient Egypt.

Girl copying her mother (19th dynasty). Image from OsirisNet.

Family was very important in ancient Egypt. Girls would trace their lineage through both the mother and father’s ancestors, and there is a lot of evidence to suggest that children were doted upon and childbirth was celebrated. Generally, all children were looked after (infanticide was not practiced) and inscriptions in tombs tell of the family’s love for their child. Children in turn, were expected to respect their parents, be proud of their families, and care for their parents in their old age.

The most important figure for a girl in ancient Egypt would have been her mother. Girls then, just as now, liked to copy their mother and mothers were expected to teach their daughters. We can see from the relief in the tomb of Sennedjem that little girls enjoyed copying their mothers.

It’s likely that girls were as equally valued as boys in Egyptian society, as seen on the statue base of Djedhor held at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Djedhor is shown on one side with his daughters and on another side with his sons, which suggests the equal importance of children in the family.

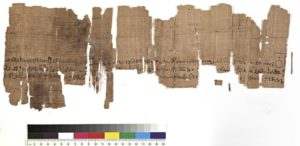

Marriage contract between Patous and Nebwotis (199 BC.). Image courtesy Papyri.info and used under Creative Commons license.

Once girls were a little bit older and started menstruating, they were expected to get married. As wives, they would start a household and raise a family while still young. From the archaeological record, it seems that Egyptian girls didn’t necessarily need permission from their parents in order to marry. Marriages were probably social arrangements that helped regulate the ownership of property. There is evidence that as adults, girls had financial independence and some earned the same pay as men. Women were able to own money and property, and make legal contracts such as a will or marriage contract. The marriage contract between Patous and Nebwotis shows that women such as Patous were included in marriage negotiations, which would guarantee her control over her inheritance and allowance.

Although girl had many rights, most became wives and mothers. Some girls grew up to be high-ranking officials, but this was only an option for the highly educated and very wealthy.

A wooden model showing women weaving (11th dynasty). Image courtesy The Global Egyptian Museum. Object held by the Egyptian Museum.

Egyptian girls would have been educated at home. Their mothers taught them practical skills, such as how to take care of babies, spin wool, weed the fields, look after animals and grind grain to make beer and bread. Girls were expected to help work in the house and fields, as well as to raise other children in the house.

Rich families employed slaves to teach children at home. Among the wealthy, a girl’s education may have involved reading, writing, and playing musical instruments. It is likely that girls and boys were educated together until they were older, when only the boys would continue their education. However, only 2% of all Ancient Egyptians were fully literate, so very few girls would have been educated.

There are examples of female doctors, officials, and even pharaohs, but this is rare. Girls could also become priestesses in Egypt’s temples, an important and powerful role. Wealthier girls would have had more freedom to become priestesses and officials, as their families did not need them to earn money through outside labor.

However, for most girls in Ancient Egypt of all social classes, their primary role was as a mother and wife.

In tomb paintings, both boys and girls are depicted very similarly, so it is likely that girls and boys played together with similar toys. Girls would have probably played with other children who lived near them, but the poorer the family, the more likely they would have been expected to work from a young age – this would have limited their play!

Dolls and toys were very common in ancient Egypt. Archaeologists have found many toys in tombs, which tells us that play was important. Wooden animals attached in a line by string and pulled along were popular, as were dolls made of wood and clay. Balls were also easy to make and would have given hours of amusement.

As girls got older, they were expected to follow their mothers more and help in the house. They would have spent their free time swimming or playing board games such as Senet or Mehen. If you feel like playing Senet, download this PDF from the Museum of Science in Boston on how to make your own board and learn all the rules!

Paintings also show girls dancing, playing musical instruments and playing piggy-back. Besides toys, banquets were popular events as the ancient Egyptians were quite sociable. Families and friends would gather to eat food and drink together while watching dancers or listening to music.

Sistrum with engraving of the goddess Hathor (late period). Image courtesy The British Museum.

Religion was very important in ancient Egypt and there were many gods and goddesses to worship. Some gods and goddesses were worshiped according to where a girl lived, while others were worshiped for a specific reason. There was no official set of beliefs and no congregations like in places of worship today. Worship was generally carried out by the priests and priestesses, and worship was not meant to make a relationship between a god or goddess and an individual. Despite this, there may have been some worship at home, with evidence of niches and altars in homes and personal offerings, especially for such instances as childbirth and fertility.

Some girls might have worked in temples, while others might have played instruments in the temples. The sistrums showen at right were possibly played by a female temple dancer, and we can see the engraving of Hathor. Hathor was a popular goddess of love, pleasure and sexuality.

Linen fabric with painting of an offering to the goddess Hathor (New Kingdom). “Linen textile with a painted inscription on one side. 1906,1013.151,AN236333001” Image courtesy The British Museum.

Girls had some choice over which gods and goddesses they worshiped. There were some very popular goddesses that tended to be worshiped more than others. Isis was the most well-known and popular. She is often presented as a women and was revered as a loving wife and mother.

Another popular goddess was Hathor – the goddess of love, pleasure and sexuality. Hathor liked music and was associated with the sistrum, as well as mirrors, which came to symbolize femininity and female sexuality. Hathor was also thought to help unmarried girls find husbands and to help them become pregnant. In “Offering to Hathor,” we can see women making an offering to Hathor.

Decorative item from the headdress of King Senusert II (12th dynasty). Image courtesy The Global Egyptian Museum. Object held by the Egyptian Museum.

Some goddesses were associated with animals that were thought to be good mothers, such as cobras. In fact, there are several goddesses that could take the form of a cobra, including Wadjet, the protector of women in childbirth. Wadjet was the local goddess of the city of Dep (Buto) who protected Lower Egypt. Her protection was shown with the sun disk, also called a uraeus, which was the emblem on the crown of Lower Egypt.

Another goddess who appeared as a snake was Meretseger. Believed to be dangerous and merciful, Meretseger was closely connected with the pyramid-shaped peak in the Valley of the Kings (called al-Qurn), and was the patron goddess of the workers who built the tombs in Deir el-Medina. She was said to punish workers who committed crimes, and was known to bring “sweet breezes” to those in pain. Meretseger was also said to appear as a cobra and spit venom at anyone who tried to vandalise or rob the royal tombs.

Merit-Ptah

Merit-Ptah, as depicted on a tomb near the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis.

Around 5,000 years before Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to earn a medical degree, Merit-Ptah was a practising physician in ancient Egypt. Known to us from an inscription dated to c. 2700 BCE, she is the first known example of a named, female physician.

The ancient Egyptians were skilled practitioners of medicine – the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 5th century BCE) noted that “the Egyptians are more skilled at medicine than any other art.” Ancient Egyptian medicine was a combination of magical ritual and medical expertise. Although their belief in amulets and spells would today be frowned upon by Western medical practice, they also understood the need for cleanliness and had an extensive knowledge of anatomy.

Merit-Ptah is identified as ‘Chief Physician’ – an important role at the royal court. This shows that Merit-Ptah belonged to the wealthiest class in Ancient Egypt, which explains her high level of education. Merit-Ptah’s role as a doctor shows that such professions were open to women, although they faced barriers such as a lack of education and social pressures. Merit-Ptah is a rare example of a named female doctor in Ancient Egypt. Others include Peseshet, who was an ‘overseer of doctors,’ and Cleopatra, a gynacologist and obstetrician.

Queen Tiye

Fragmentary statue of Queen Tiye, currently held by the Louvre. Image courtesy Rama on Wikimedia, licensed creative commons.

Queen Tiye, or Tiy, ruled Egypt in the 18th Dynasty (c. 1550-1292 BCE) alongside her husband, Amenhotep III. She was notable for the exceptional power she wielded, made even more remarkable because she was a commoner by birth.

It was common convention in Ancient Egypt for the ruler to marry their brother or sister. As a prince, Amenhotep defied convention to marry Tiye. Although a commoner, Tiye had a very privileged upbringing: both her parents held high positions in the royal household, and Tiye grew up at court.

As queen, Tiye held power in equal measure to her husband. She is featured prominently on the king’s monuments and depicted in statuary at the same height as her husband (a sign of equal status). The pair presided together at important festivals, met with foreign dignitaries, and directed domestic and foreign policy. Tiye’s name even appears within a cartouche, just as Amenhotep’s did. While common for pharoahs, it was more rare for women to be included in cartouches. Only wives and daughters who held special positions were given the honor, such as Tiye.

After her husband’s death, Tiye’s influence continued through her role as queen mother to the new king, Amenhotep IV (later known as Akhenaten). She continued to play an important role in the political life of Egypt, maintaining a direct correspondence with several rulers, including the king of Mitanni, Tushratta.

Tiye’s mummy was found by archaeologists in the tomb of Amenhotep II in 1898. First identified as ‘The Elder Lady’, it was only when we discovered more about the reign of Akhenaten that Tiye became known by name. Tiye deserves to be remembered as a great queen, who exercised immense power over Ancient Egypt at the height of its wealth and influence.

Egyptian Girls

In Ancient Egypt, girls seemed to have been valued. Those families who could afford to probably educated their daughters, but this was limited to the wealthiest of families. While some girls went on to hold powerful positions, most would have been expected to do their duty as a daughter and mother. Despite this, there were some freedoms. Girls played and often worshipped freely. Lack of detailed evidence though, makes it hard for us to give an in-depth description of their lives, but from small pieces of evidence we can begin to build up a picture of what we think it might have been like.

Fun Fact: Girls could hold the highest position in the land: Pharaoh. Yet this was incredibly rare. One of the most accomplished pharaohs in history was a woman: Hatshepsut, a royal princess whose military, building, and social accomplishments are still debated today. In this video by TED-Ed, discover Hatshepsut – and how she was nearly wiped out of history.

Craft Time!

Check out these tutorials from the Petrie Museum!

China

Figure (woman) with hands clasped. High head-dress, perished. Made of blue glass. Circa 1050 – 221 BCE, Zhou dynasty, Shanghai, China. Currently held by The British Museum.

In this episode of our GirlSpeak podcast, we explore what a girl’s life would have been like during two of the oldest periods in Chinese history: the Shang and Zhou dynasties. Together, these dynasties lasted from 1675 to 256 BCE, and saw a lot of changes in how girls lived and were given status.

Maya

Tetrapod Bowl, c. 1st to 4th century, Guatemala. Wide-mouthed bowls like this were used for presenting or serving food, and might have been highly valued since it took a high level of skill to make.

A Day in the Life: Citlali, 8 years old, Ceren

Today is a special day and I am very excited. My mother and I leave on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Ix Chel, the goddess of fertility, midwifery and medicine. We go to pray and leave offering so that one day I may have a baby brother. I already have 3 younger sisters but my father wants a boy to succeed him.

My father is a very important man, who rules the town we live in. He loves us dearly but he needs a boy to rule after him and continue the line of our house. I am excited to go to the shrine with mother, but I will miss my lessons at school. Mother says those may end soon, as I need to learn how to run a household. When we return, I will continue helping grind the corn – but will also learn how to make corn into tamales. It takes mother so long to make them; I don’t really mind, as the tamales are always my favorite. The only thing I love more is cacao, but I can only drink it on special days.

Luckily, my new duties will still allow me time to play my flute. I also enjoy playing ōllamaliztli, this is a ball game where we hit a ball between two players using a bat. I am really good at it and I wish I could play in the rituals but girls are not allowed.

One day I will marry an important man like father and run his household and bear him many sons. I don’t really mind who it is, though I hope he might be one of the strong ball players that I see on festival days. But today is a good day, and I will pray very hard that my mother makes a baby brother for me.

We’re going to focus on girls’ lives during the Preclassical Period (from 2000 BCE to 250 CE). At this time, the Maya were made of smaller groups like the Olmeca. By 250 CE, however, these smaller groups had formed a larger civilization – the Classical Maya – based around large cities like Teotihuacan and El Tajin. Most of our evidence for Mayan life comes from the Classical period, in the form of burials and texts on monuments. We assume that Mayan girls held similar status throughout Mayan civilization.

The Classic Maya period lasted until the final end of Maya civilization in 900 CE, when it collapsed for unknown reasons. Interestingly, the Maya people are still alive today – and they still speak their native language (Nahuatl) and continue many ancient Maya traditions. By combining archaeological evidence with ethnographic studies of modern Maya peoples, we’ve uncovered a surprisingly complex way of life where girls are integral to society.

Jaina-style female effigy figure, c. 600-750 CE, Campeche, Mexico, Jaina Island area. A woman sits cross-legged and grinds maize with a mano (cylindrical grinding stone) and single-footed metate (flat grinding platform). Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Bequest of Betty Bartlett McAndrew.

Maya girls lived in a highly stratified society – you were either an elite or a commoner. Land was held communally, and many people lived in small communities that eventually became cities. Many of these cities were named for women – as revealed by Dr. Shankari Patel of the University of California Riverside. Dr. Patel’s research reveals that many objects hidden in storage are of spindle whorls, female icons, and figurines used in funerary rituals that reveal women were primary actors in Maya society.

Maya girls also had extensive home lives. They lived in a network of city-states, with some cities having as many as 120,000 residents. At sites like Teotihuacan, Tikal, Calakmul, and Copan, commoners lived in thatched buildings and worked as farmers, laborers, servants, and craftspeople. They used a variety of technologies to cultivate domesticated and non-domesticated plants, or to specialize in lithic and cloth production.

Incense burner base, c. 400-550 CE, Guatemala. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Cacao was both currency and a prestigious gift. The goddess of cacao and fertility, Ixcacao, bears a ripe pod, with cacao flowers in her hair and a feathered divining mirror on her chest.

Girls would help to process a variety of foods, including maize, beans, squash, chili peppers, shellfish, deer, and small mammals. They also participated in many feasts, which were linked to rituals. One of the favored drinks for these feasts was cacao, which was consumed as early as 1900 BCE. Girls would serve cacao as a drink in chocolate pots.

Want to try a Maya cacao drink? Here’s a recipe!

Girls also produced a variety of textiles and ceramics. They used different objects in spinning and weaving depending on their social status. Evidence from Ceren, which was buried by volcanic ash in 600 CE, indicates that textiles were considered artworks. Textiles were produced using spindle whorls, and the high number of weaving tools found throughout residences indicates that this was a major craft for women of all classes.

Maya stucco glyphs displayed in the Archaeological Museum of Palenque. Photo by Kwamikagami of Wikimedia Commmons, 2004.

In the beginning, the Maya probably spoke one or a few languages; but over time, this evolved into over 30 different languages. The most common was Ch’olan, used in writing. The Maya system of writing was highly complex, featuring more than a dozen subsystems of hieroglyphic scripts. They used this writing to produce monumental texts and books, though the majority of their books were destroyed by the Spanish conquistadors. Only 4 confirmed books have survived, indicating that all of the Maya were highly literate and recorded their learning and rituals.

The Maya also had a system for mathematics and calendaring. The first concept of zero was created by the Maya. The Maya also used their math skills to develop a complex calendar that recorded the lunar and solar cycles, eclipses, and movement of the planets. This calendar was more accurate than any contemporary system in the world and was tied to their rituals. You can learn more about the calendar system here.

This high degree of literacy suggests a centralized system of schooling. Girls went to these schools. Representations of female scribes in Mayan art have survived, and these women called themselves “aj tz-ib” or “one who writes or paints.” However, we are not sure how many female scribes actually existed, or whether it was common for girls to attend school.

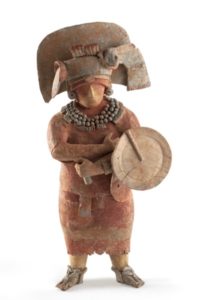

“Seated female effigy whistle,” c. 600-750 CE, Campeche, Jaina Island area (Mexico). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Maya girls loved to play. Archaeological excavations have revealed a variety of toys, including wheeled toys, musical instruments, and rattles.

Girls loved to play music. Some of the most common instruments found in elite residences are small whistles, which have one resonator chamber and two stops of the same size to produce three notes. These whistles often have human or animal heads attached to the resonator. It is unclear if these heads are mythological or effigies.

Other musical instruments include flutes, clay bells with clappers, turtle carapaces, ceramic drums, and bone rasps. Girls are often depicted in Maya art playing these instruments, wearing either simple or elaborate attire. Since musical instruments have been found in and around all types of buildings, and most often in side rooms or burial chambers that housed women and children, it’s highly likely that music was an integral part of girls’ lives.

Cylinder vase (ballgame scene),” c. 750-850 CE, Belize or Mexico. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This scene is possibly related to the ritual Mesoamerican ballgame, including three women wearing long dresses and five male figures wearing black shorts and black short-sleeved tunics

Maya girls may also have participated in the famous Maya ballgame called ōllamaliztli or pitz. Played as early as 1400 BCE, this ballgame was ritualistic and had many different variations. It was probably similar to racquetball, where the aim was to keep a rubber ball in play by striking it with the hips, arms, or bats. The game may have been played during rituals, and is linked to the myth of the Hero Twins. Accounts from Spanish explorers record the ballgame as being used to determine who would rule over the city, perhaps providing a way to resolve conflicts without warfare. We also have evidence that it was played by women and children as a simple game, but we’re unsure if girls participated in the ritual aspects.

Front Face of a Stela (Free-standing Stone with Relief), 692. “Waka Stela 34.” The Cleveland Museum of Art. In this image, a royal woman marks the passage of a twenty-year period known as the k’atun. She originally stood in a plaza next to a portrait of her spouse, with whom she ruled El Peru-Waka, a provincial Mayan town. She may have even held higher authority than her husband, serving as a military governor.

Girls were a major part of Maya religion. The Maya were ruled by a divine king or queen, who was the center of political and religious power. Scholars have long assumed that Maya society was patrilineal, with queens only ruling when there were no male heirs. Yet this has recently been challenged by the work of Dr. Kathryn Reese-Taylor.

At Naachtun in northern Guatemala, Dr. Reese-Taylor found depictions of a queen on Stela 18, showing her with a battle shield strapped to her arm and standing on the back of an enemy captive. Intrigued, Dr. Reese-Taylor looked at many other sites. She identified many sculptures at Naachtun that depicted both kings and queens as conquering heroes, including this representation of Lady K’abel currently held by the Cleveland Museum of Art. She also confirmed the presence of warrior-queens at Coba, Naranjo, and Calakmul – with over 10 different queens sporting headdresses and symbols of war. Taken together, her research has revealed that northern Maya cities prized their female ancestors and placed great value on royal women – many of whom played central roles in politics.

Dr. Reese-Taylor’s findings are also supported by recent discoveries. At Tombs 1 and 2 of Yaxuna, the burials of women had more grave goods and showed more care than those of men, suggesting the women ruled the city. At Waka, archaeologists found a tomb under the main courtyard of the palace that held the remains of a woman surrounded by 23 offering vessels and hundreds of pieces of jade, beads, and shells. The women was wearing a huunal, a jewel worn only by royalty of the highest status and which indicated she was a warlord. And in Copan, the 5th-century queen buried in the Margarita Tomb is dressed in garments of precious greenstone, shells, and feathered bird heads as she rests on a massive carved funerary slab.

Yaxchilan Lintel 25, c. 600-900 CE. The British Museum. Lady Xook, wife of Shield Jaguar II, is having a vision with regard to a Teotihuacan serpent in the hallucinatory stage of the bloodletting ritual.

Girls also held a high place in Maya mythology. The Moon Goddess, frequently depicted in codices and murals, was associated with sexuality, procreation, fertility, vegetation, and disease. She existed in many forms: as a wife, grandmother, or even independent of male escort.

The Q’eqchi myth of the Sun and Moon tells us that the Moon Goddess was wooed and captured by the Sun. Her father, angered by this, had his daughter destroyed and used her menstrual blood to create creatures that spread poison and disease – hinting that women were powerful, but that menstruation may have been taboo. Yet the evidence for this is conflicting. In Maya society, blood was a powerful ritual element to contact or manifest spiritual beings – and girls participated in bloodletting rituals. Men also emulated menstruation by performing blood-letting on their genitals, suggesting that women’s ability to menstruate may have made them more connected to the spiritual realm.

Fun Facts: Mayan Beauty

Ixchel

Ixchel in the Dresden Codex, circa 14th century CE. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Ixchel, the goddess of midwifery and medicine, was probably known to the PreClassic Maya. She was usually depicted as an old, plump woman, with jaguar ears, sometimes with claws instead of hands. Images of Ixchel often show her wearing a snake headdress – with a live serpent – and carrying an inverted water jug. These attributes suggest Ixchel’s role as a midwife, sharing parallels with Aztec earth goddesses, who were also invoked as midwives. However, she may also have had a role as a female warrior, as suggested by her depiction as a jaguar goddess.

A number of shrines were dedicated to Ixchel, and many are still visible throughout the Yucatan. Her shrine on the island of Cozumel was especially popular and one of the most important pilgrimage sites for the Maya. Her relevance to childbearing meant that she was particularly venerated by women. In the Classic period, she also had a sanctuary on Isla Mujeres. According to Diego de Landa, the island’s sole inhabitants were the priestesses of Ixchel, who ruled over a court of women. Ixchel is still honored to this day, especially on Cozumel, where many women dedicate prayers to both Ixchel and the Virgin Mary.

Lady K’awil

Figurine of a Mayan queen, probably Lady Kabel, found as part of a cache of 23 ceramic figures excavated from a burial site at El Peru-Waka’ in 2006

Not much is known about the rulers of the PreClassic Maya states. It is easy to presume that rulers were men, with power inherited through the patrilineal line. Yet, the existence of powerful female rulers in the Classic period suggests that women did rule, perhaps more often than we think.

Evidence from sites such as Naachtun, Yaxuna, Waka and Copan supports the existence of powerful female rulers among the Maya. Some archaeological evidence, such as the murals at Naachtun, depict both men and women as conquering heroes. This demonstrates that elite women could also partake in warfare, and were not restricted to the more domestic roles which we see in the majority of Maya society.

Lady K’awil ruled the Mayan area of Toniná in the 8th century AD. Evidence suggests that she came to power after the failure of the previous two rulers, Ak Motz and Zotz Choi, both male. Lady K’awil may have been selected as ruler through her military victories. Murals document her reign: they depict Lady K’awil seated on a throne, with captives at her feet. After Lady K’awil’s death, Toniná became matrilineal, reflecting the success and prosperity that it enjoyed under her rule.

Maya Girls

There are many problems with studying Maya girls. First, Maya society went through periods of growth and collapse – often building over previous sites or letting those sites succumb to the harsh jungles. Second, the arrival of the Spanish in 1512 meant that many Maya artifacts and sites were destroyed, though a few were shipped to Europe, where they remain hidden in the storage rooms of major museums.

Despite these setbacks, we do know some things. Maya girls lived in a highly stratified society. Some were commoners, who worked as farmers, laborers, or artisans. Others were royalty, acting as wives and mothers or ruling as warrior-queens. Both classes produced a variety of textiles and ceramics, spoke many languages, and learned complex systems of reading, writing, and mathematics. Maya girls also loved to play, especially with musical instruments or in the ballgame. And new evidence is revealing that girls’ lives were far more complex than we assumed – perhaps even redefining what we believe about Maya society.

Though Maya civilization collapsed by 900 CE, the Maya have prevailed. Their culture still flourishes in Central America, as shown in this video from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Reflections on Ancient Girls

Girls’ lives in the ancient world were far more complex than we ever thought. Whether heading their clans in the Indus Valley, weaving textiles of great renown in Greece, playing Senet and participating in Egyptian religious ceremonies, or ruling the mysterious cities of the Maya, girls were far more than the “wives and mothers” archetypes ascribed to them.

Growing up, many of us had no idea that girls’ lives were so varied or that they held prominent positions. Standard history textbooks didn’t even include girls, unless they had defied society in a monumental way. As the stories of these ancient girls came to life, our team was constantly challenged to fact-check, research more, and keep exploring until we found the truth.

But, as with most of history, the full picture is still out there. It’s up to the next generation of anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, and explorers to uncover the mysteries about girls’ lives that remain – and to prove that girls are, and have always been, far more important and incredible than previously thought.

Credits

Special thanks to Nicky Lacourse for designing the exhibit’s button, and banner, and for providing her expertise on Maya civilization.

Educational materials developed by Hillary Hanel, Rebecca King, Lucy Rivers, and Alex Burrows. Coloring pages by Alex Burrows.

Want More?

Ancient Mesopotamia by Allison Lassieur

Hands-On History Mesopotamia by Loma Oakes

Ancient Mesopotamia exhibition by The University of Chicago

Khan Academy’s lessons on Ancient Mesopotamia

China

DK Eyewitness Books: Ancient China by Arthur Cotterell

The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC by Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy

“Crash Course World History: Mesopotamia”

Ancient Egypt

Awesome Egyptians by Terry Deary and Peter HeppleWhite

The Story of Egypt by Joann Fletcher

Egyptian Things to Make and Do by Emily Bone

How to read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A step-by-step guide to teach yourself by Mark Collier and Bill Manley

Portrait Head of Queen Tiye (video), Dr Beth Harris and Dr Steven Zucker

Egyptian Art on Khan Academy

“Crash Course World History: Ancient Egypt”

“The Pharaoh that wouldn’t be forgotten” (TED-ED)

Ancient Greece

“The Science Behind the Myth: Homer’s Odyssey”

Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization by Robert Garland

Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece by Joan Breton Connelly

Women in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook by Bonnie MacLachlan

Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: An Anthology by I. M. Plant

Goddess Girls by Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams

20 Fun Facts about Women in Ancient Greece and Rome by Kristen Rajczak

Indus Valley

Mystery of their Mastery of Water

The Story of India (PBS)

The Indus: Lost Civilizations by Andrew Robinson

Indus Investigators: Mohenjo-Daro Mystery

Maya

Women in Ancient America by Karen Olsen Bruhns & Karen E. Stothert

Ancient Maya Women by Traci Arden

The Ancient Maya by Jackie Maloy

Rain Player by David Wisniewski

Discover the sites of the Maya (Smithsonian)