Becoming Girl

Becoming Girl explores various representations of girlhood by contemporary artist Chaya Avramov.

The concept of ‘Becoming-Girl’ originated from Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, a peer-reviewed Deleuzian journal. In July 2011, an issue dedicated to the concept of ‘Becoming-Girl’ was published. It included a collaborative essay, ‘Becoming-Girl-Museum’ written by the team here at Girl Museum. This essay de/re-constructed what Girl Museum is/intends for our audience/selves.

You can read this essay in the toggles below.

Becoming Girl Museum

by Ashley E. Remer, Kathleen Weidmann, Lara Band, Briar Barry, Miriam Musco, and Julie Anne Young

Girls do not belong to an age group, sex, order, or kingdom: they slip in everywhere, between orders, acts, ages, sexes. [2]

We are girls, belonging nowhere yet existing everywhere; constructed by family, community, and society; deconstructed by academics and theoreticians; reconstructed through our words and deeds. We are many voices writing in a singular space, from the four corners of the round earth, with multiple intentions and one goal. We are Girl Museum, entirely online and the only museum in the world devoted to girlhood:

Girl Museum is a virtual space for research, exhibitions and education centered wholly on the subject of being a girl. Our aim is to explore and document the unique experience of growing up female through historic and contemporary images, stories and material culture. Through the history of art and cultural images, we want to raise global awareness about the realities and issues, both nature and nurture, facing girls yesterday, today and tomorrow. [3]

Collaboration defines our virtual reality. As a museum without walls, indeed a museum without objects, we are functioning outside the customary expectations of what both a museum is and should be. With the current trajectory of democratization and museums as social spaces, [4] it seems only a natural progression to exist as a free space open 24/7/365.

‘Girlhood’, our dedicated subject, is also beyond the sphere of orthodox discourse. Either seen as unimportant or simply not seen at all, many museums would rather take a critical look at collection items containing sunsets or cats than address representations of girlhood in anything beyond a superficial manner. We exist to challenge this situation.

Projected out into a pixel-based world are the powerful stories of us all—past, present, and future—necessary to share and understand, growing rhizomatically, constantly creating newness and variation through inter(net)connectivity. We resist the conventional, striving to (re)define ‘girlhood’, while simultaneously unfixing ‘girl’. We are (Becoming-) Girl Museum.

Becoming

Representations of the human body, then, are particularly powerful pieces of material culture: almost-mirrors in which people can see themselves, see how others see them, and see how existence ‘should’ (or should not) be experienced. They provide a frame of reference and engender Becoming- through presentation, interpretation, and interaction. The Girl Museum exhibition Across Time & Space, [6] explores these ideas through an assemblage of 25 depictions of girlhood across nearly 3000 years and 10,000 miles.

In essence, these depictions show identities: personal, conceptual, or a mixture of both. But ‘identity’ as a fixed idea does not and cannot exist; in the Deleuzian concept of difference, “… there is no identity, and in repetition, nothing is ever the same. Rather, there is only difference: copies are something new, everything is constantly changing, and reality is a becoming, not a being.” [7] What we see in the image is not the subject or the concept ‘girl,’ but the artist’s interpretation of the subject (and the concept ‘girl’), an interpretation influenced by as many Becomings- as those that will come after to interact and create anew.

By bringing existing things together in new assemblages we create new effects, new ideas, new realities, more Becomings-. In removing the depictions of ‘girls’ from their previous contexts and placing them in a new assemblage, Across Time & Space looks at what Becoming-girl meant in the past in the hopes to empower those who are Becoming-girl in the present and future. The images and accompanying text encourage thinking about why and for whom the depictions were created.

The roles, relationships, and qualities of the girls depicted are examined by looking at themes such as religious and familial devotion; place and status in society, work, and play; and expectations placed upon the girls (familial, societal, and personal). Through careful and critical examination of these fixed-identities, the goal of both Girl Museum and Across Time & Space is to encourage visitors to confront their fixed notions of ‘girlhood’, and instead determine their own ideas of what it means to be a ‘girl’.

Like any museum, Girl Museum has created exhibitions, thematic assemblages and groupings of the ‘collection.’ Visitors interact with and explore the ‘collection,’ finding curatorial guides and an encouragement (in the form of curatorial notes, admittedly) to formulate individual opinions and ideas beyond what the curatorial guides suggest. Inherently, however, curatorial guidance can be limiting. Eileen Hooper-Greenhill states:

If new taxonomies mean new ways of ordering and documenting collections, then do the existing ways in which collections are organized mean that taxonomies are in fact socially constructed rather than ‘true’ or ‘rational?’ Do the existing systems of classification enable some ways of knowing, but prevent others? Are the exclusions, inclusions, and priorities that determine whether objects become part of collections, also creating systems of knowledge? Do the rituals and power relationships that allow some objects to be valued and others to be rejected operate to control the parameters of knowledge… ? [8]

It is a difficult line to walk as a curator—not everything can be presented (not even on the internet), so choices are made as to what to include and/or exclude. But whenever something is included or something is excluded, a determination has been made, one that can potentially limit the free flow of movement, of growth of thought, changing Becoming- to Being-. Deleuze and Guattari argue that assemblages are loose, disparate, and can promote a variety of interpretations (Becomings-) because of their disparate nature. [9]

Museum ‘collections’ and exhibitions may contain a variety of assemblages, large and small, interrelated and changeable, but they are still potentially restricting by the very nature of their limits—the components of the ‘collection.’ As such, the best a curator can hope for is that for the assemblage presented, the very nature of the ‘collection’ or exhibition will be transparent enough to allow visitors to find their own meanings, reach a new understanding, be better informed, or be newly inspired, be it because of—or perhaps in spite of—the ‘collection’ assembled.

Girl

What makes up Girlhood?

Everything Really. [10]

As a girl navigates the world, she shapes and reshapes her identity and her sense of self with the information she finds and encounters there. And this is one of the goals of Girl Museum— to provide information on girls and girlhood, past and present, through space and time, to show that being a girl is only limited by the girl questioning who she is and wants to be. Girl Museum emphasizes what it is to be a girl, [11] not a child, not a woman, and not male.

With different historical, cultural, and social interpretations—all of which are being added to or modified all the time—we have found that the definition of ‘girl’ is ever-changing, and dependent upon the circumstances of definition – who defines? When? Where? Girl Museum is interested in progressions and modes of expansions, yet also acknowledges that every girl born on the planet is a new Becoming-; the culmination of a unique set of circumstances, abilities, and genetic programming. These are only shackles to those who perceive them as such.

Deleuze and Guattari describe the concept of smooth space as “… filled by events or haecceities, far more than by formed and perceived things. It is a space of affects, more than one of properties.” [12] In other words, a space is smooth, ripe for inspiration, when its materials and concepts are not strictly defined but instead can inhabit a number of different characteristics as determined by the inhabiter(s) of the space. Girl Museum strives to be a smooth space for girls to move through, particularly with exhibitions such as the Heroines Quilt. [13]

Girls (and Becoming-girls) can create and contribute content based on their views and experiences, and interact with the content created by the views and experiences of other girls. With each new submission, the Heroines Quilt grows and changes to reflect the inspirations of its contributors. Held together by a theme, the disparate parts make up a new whole, one which illustrates the differences between the submissions—real vs. fictitious, modern vs. historical, famous vs. family—while still highlighting the inherent ‘sameness’ of the submissions: the ability to inspire and positively influence girls. In this way the goal of collecting multiple, diverse viewpoints from girls on what constitutes a heroine, is fulfilled on a global, easily accessible platform.

Heroines Quilt, April 2010

Specifically, the ongoing exhibition Heroines Quilt features short biographies of girls and women that visitors consider to be positive role models (or, as the name suggests, heroines). The exhibition asks visitors—specifically girls and women—to “… send in a short paragraph about who your girlhood heroine was, why they were important to you and what impact they may still have on your life.” [14] Although Girl Museum did create some limitations on the exhibition space by asking for a heroine and preferring that the submissions come from girls/women, the question was left open so that visitors (girls) could choose someone “real/fictional, contemporary/historical, [or] famous/local.” [15]

We did and do not want to define what a woman or a heroine should be, but instead allow girls from any culture to freely express what they each find to be important and inspiring, the qualities they admire and would perhaps like to emulate. Within this exhibition space, girls can encounter multiple and varied properties of heroism rather than being presented with only one model of being, thus allowing for contemplation, self-determination, and education.

In a two-part structure, the Heroines Quilt first provides a forum for girls to freely express themselves and their ideals, and then constitutes a global venue for sharing and exchanging these qualities and ideas. The exhibition has the added benefit that the girls (contributors) themselves determine who is included in the exhibition/assemblage, instead of being told who they should look to for role models.

The squares of the Heroines Quilt showcase a diverse, multiethnic array of women spanning many centuries, ages and social structures. Some of the heroines are real (Amelia Earhart, Julia Child), while others exist only in the imagination, between the covers of a book or on television (Anne of Green Gables, Lisa Simpson). Some were inspired by personal goals, by the convictions of their religious beliefs, or by a sense of justice. Some are seen as heroines because of the words they wrote or the journeys they made or the acts they committed. Each was and is unique in her qualities, but each represents positive characteristics that speak to the needs and ideals of girls worldwide. And the list is ever growing.

The smooth space created by the Heroines Quilt allows girls worldwide to experiment with different ideas of both heroism and Becoming-girl in an open, organic, and encouraging environment. The exhibit offers not a single path for growth and development, but a myriad of ways for girls to explore what inspires them and what they believe makes a woman into a role model, into who they are and who they wish to be. Instead of a fixed-notion, one-size-fits-all template for girlhood, girls are presented with many different properties and qualities that they and the women around them can inhabit.

The Heroines Quilt gives girls a space to express their inspirations and continues to provide a way to exchange ideas about what is individually meaningful, and each girl who visits can take away new ideas about their becoming. In this way the exhibit not only encourages girls to speak in their own voices, but also to listen to the voices of other girls around them and to the stories in which each finds significance. From this process, girls not only learn to express themselves but to take meaning from diverse sources, in order to form a larger picture of themselves and the ideals to which they strive.

Museum

Deleuze’s rhizome is an open system that emphasizes the nomadic character of life and language. [16]

Girl Collage, Girl Museum, 2010

Girl Museum seeks to represent the ideas of ‘girl:’ the personal and shared experiences of being a girl and the assorted aspects of girlhood throughout recorded history. Paintings, etchings, photographs, and sculptures are found to represent an idea of ‘girl’ that arises from a specific moment or an established society view. Girl Museum’s inaugural exhibition, Defining our Terms, [17] sets out the Girl Museum ethos – “For us, ‘girl’ is not defined as property, victim or the opposite of ‘boy’.” [18] This last phrase, ‘the opposite of boy,’ and ‘girl’ being defined as existing against something else is important in the ideology of Becoming- and not Being-. [19] Defining our Termsrecognizes there is not beginning or end to the definition of girl. In fact, the term ‘girl’ has changed in meaning; prior to the sixteenth century, it referred to a child of either sex. The notion of ‘being a girl’ or having a ‘girlhood’ is only a relatively recent phenomenon. [20] As such, definitions of ‘girl’ and ‘girlhood’ will continue to change as ideas and expectations change.

The conjoining of different ideas of ‘girl’ and ‘girlhood’ is at the heart of Girl Museum. Girl Museum seeks to “explore the importance of girlhood of the past, present and future through collaborative and interactive exhibitions and projects.” [21] The democratic sharing of experience, knowledge and the acknowledgment of different streams of understanding (and Becoming-) are indicative of the changing nature of ‘girl.’ ‘Girl’ cannot just be defined by one word or idea, because “girls do not belong to an age group, sex, order, or kingdom: they slip in everywhere.” [22] In this time of increasing intolerance and comfortable ignorance, Girl Museum seeks to address any definition of girl and to promote global connections and facilitate learning about different cultures.

One way Girl Museum does this is by disrupting the traditional pathways of art history and anthropology, examining traditional images and stories with a keen eye on the subject matter. The dominant discourses of art history are so pervasive that it is hard to know what not to take for granted. There is a massive pantheon of artistic demigods who, over time, have been pardoned from responsibility for their creations. This is not to say that Girl Museum is interested in slashing and burning any image that seems sexist or exploitative, just that it is important to take an informed second look, from the perspective of taking girlhood seriously.

Girl Museum has four exhibition series: ‘Girlhood in Art’, ‘Art of Girlhood’, ‘Girls in the World’, and ‘GirlSpeak’. The first looks at the fine arts, the second takes an anthropological perspective, the third deals with contemporary social issues, and the last is our interactive space. Along with the blog, where the Junior Girls (interns) present information about what is going on in the lives of girls around the world, ‘GirlSpeak’ provides an opportunity for any girl or group of girls to participate in the Becoming-Girl-Museum. Any girl (not just the Junior Girls) can submit ideas for exhibitions, projects, or events they would like to see Girl Museum produce. Additionally, girls can create original artwork and contribute it for inclusion in an online show. It is in the ‘GirlSpeak’ exhibition series that Girl Museum truly hopes to make an impact on both global and local levels, to give girls confidence in their process of Becoming-, and satisfaction in producing original work and knowing that it (and therefore she) is worthy of being in a museum’s collection.

Traditionally, museums are collections of objects, concepts, definitions, people, and thoughts. Virtual museums, by their very nature, are composed of all these elements, but can be pulled from universal experience and not linked to any single or specific collection. Though they can be hindered by a lack of physical resources, this can also be advantageous because virtual museums do not have to be static. The virtual assemblages of objects, concepts, and definitions can feed off each other, generating new concepts, more definitions, new ideas, and, as many museums move toward a more interactive experience, new objects. [23] Girl Museum envisions a merging of ideas and images that can be used in various ways to create exhibitions, to propose new ideas without placing these ideas and assemblages in a fixed environment. The idea of celebrating ‘girlhood’ is used to bring disparate elements together, which in turn are used to cultivate different definitions. By the “… jumbling together of discrete parts or pieces that is capable of producing any number effects,” [24] Girl Museum—and any virtual museum—can use any number of image-objects to create a coherent whole, but a coherent whole without a single “dominant reading.” [25] This coherent idea is not merely one; it can also be another, an ‘other.’ It is an assemblage trying to resist restrictions and limits. Girl Museum strives to show that there is no beginning or end to the representation of ideas; rather, the availability of collections, images, and ideas from all over the world can help the continuous evolution of definitions and accepted norms.

Celebrate Girl, Sara Morsey, Acrylic on board, 2009.

As a construct without declared limits and unfound boundaries, Girl Museum is a new sentience seeking to grow and expand in a virtual world, beyond the need to separate ‘girl’ into a multitude of sub-categories. In an age where information and misinformation can be found around every corner of the Internet, Girl Museum strives to provide a space where everyone can explore all the natures of girlhood. We are as interested in what has been and what currently is as to what might be in potential futures, to liberate possibility to see what a life may do and where a life might go.[26] Girl Museum’s website is intended to take on new directions, to travel and grow in response to “unnatural participations”[27] with individuals, groups, NGOs, educators, other museums, and so on. How successful this endeavor is will be determined in time.[28]

Girl Museum has embraced the Internet as a valuable and appropriate forum for showcasing and exploring issues relating to social history, current events, literature, art, and popular culture relevant to girls today. This does not mean we are unaware of the many negative ways in which the Internet can impact girls around the world. The Internet’s shrouded and deceptive nature provides users with the ability to either remain anonymous or adopt a new persona altogether. As a result, predators are able to target young people, especially girls.

Crimes are committed without fear of witnesses, making it extremely difficult for authorities to combat cyber crime effectively.[29] Conversely, the extremely public nature of the Internet allows the spread of private information as users—particularly younger users—are naive about the levels of security which private forums seemingly provide. Alternately, they may fail to grasp the permanence which a piece of information may obtain once posted on the web.

The media is awash with cautionary tales of girls who have been embroiled in cyber bullying, child pornography and identity deception. In 2006, Missouri teen Megan Meier killed herself after the mother of a former friend befriended Megan and then harassed her through a fictitious MySpace profile.[30] In 2009, three female Pennsylvania high school students were charged with manufacturing, disseminating, or possessing child pornography after ‘sexting’ nude images of themselves to male classmates (who were also charged), unaware of the potential spread of the images should they have been uploaded to the internet.[31] Parents of today’s youth face previously unknown challenges as they strive to protect and teach their children to be safety conscious in an ever-evolving technological world.

Girl Museum strives to provide a safe space for all Internet users, but for girls in particular. We attempt to confront these problems, which can disrupt the educational, recreational, and social benefits that can be obtained when girls embrace the online community. By directly facing these issues and corresponding images through exhibitions and analysis, Girl Museum recognizes its concurrent backward and forward looking social roles and responsibilities. We hope that, in some small way, exhibitions like the Heroines Quilt can combat the negative, limiting views of girls (and women) that can be found on the Internet and in the media.

One concern facing Girl Museum is the ability of digital spaces to influence and determine identity, rather than suggest different ways of Becoming-girl: “The [digital space] can become a performative space for both the artist and the audience.”[32] This may be true for fixed digital spaces, where only one or a few modes of Becoming-girl are accessible. But at Girl Museum, many ways of Becoming-girl are presented, which defy the boundaries of temporality, geography, and culturally imposed gender; furthermore, it is left up to the viewer to accept or reject the implicit message of girlhood in each representation. For example, in Across Time & Space, Becoming-girl is presented through the lens of girlhood across many societies, over different millennia, with the ideas of each girlhood cemented in the restrictions of each culture.

In the Heroines Quilt, girls around the globe were invited to propose their ideal heroine, and the submissions reflected a myriad of ideas concerning the definitions and meanings of girlhood. In this way, digital visitors are not merely receptive audiences being conditioned into a narrow definition of Becoming-girl. Rather, the audience is given options and context for Becoming-girl from which to choose, and in some cases the audience is the digital arbiter of content.

None of Girl Museum’s exhibitions or curricula shy away from ‘difficult’ themes; Schiele and Gauguin’s relationship to girls are explored, as is the possible depiction of rape and prostitution in Degas’ Intérieur.[33] Addressing these helps girls question the representations of themselves and other girls created by others, something that is made quite explicit in the closing words of the exhibition: Look around at the images of girls found in contemporary art and advertising. What does that say about us?[34]

Edgar Degas, Intérieur (nickname The Rape), 1868-9. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons.

Ultimately, through exhibitions such as Across Time & Space and the Heroines Quilt, Girl Museum aims to facilitate Becomings-self chosen through resistance to Beings-imposed. Girl Museum is an illustration of the positive power of rhizomatic collaboration among, and for, girls. Just as material culture holds power to create and recreate, to Become- and affect Becomings-, so do we:

Each thing can become otherwise, even if its present being can be calculated and measured quite precisely. By virtue of its inherence in the whole of matter, each object is more than itself and contains within itself the material potential to be otherwise and to link and create continuity with the durational whole that marks each living being.[35]

Or as Catherine Twomey Fosnot puts it, “we as human beings have no access to an objective reality, since we are constructing our version of it, while at the same time transforming it and ourselves.”[36]

Ideally, Girl Museum functions rhizomatically: with each connection made, with each new girl that contacts us, our outreach grows exponentially in new and exciting directions. And though Girl Museum is a virtual place, we support and encourage opportunities to connect in real life—at events, exhibitions, and community projects. We are always open to ideas, comments, and suggestions for projects, collaborations, and exhibitions, produced both online and locally. “We are about acknowledging and advocating for girls as forces for collective responsibility and change in the global context, not as victims and consumers.”[37] Our duty is to ensure the synaptic cohesion of our mission, to welcome girls as they are, honor the changes that they explore and endure, in the never-ending process of perpetually Becoming-Girl.

Bibliography & Notes

Bibliography

Brunker, Mike. “‘Sexting’ Surprise: Teens Face Child Porn Charges.” MSNBC.com, January 15, 2009. Web. «http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28679588/ns/technology_and_science-tech_and_gadgets/t/sexting-surprise-teens-face-child-porn-charges/». Accessed 10 May, 2011.

Deleuze, Gilles. The Logic of Sense. London: Continuum, 2004. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1987. Print.

Doyle, Denise. “Art and the Avatar: The Kritical Works in SL Project.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 4.2-3 (2008): 137-153. Print.

Driscoll, Catherine. “The Woman in Process: Deleuze, Kristeva and Feminism.” Deleuze and Feminist Theory. Eds I. Buchanan and C. Colebrook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University, 2000. 64-85. Print.

Duclos, Rebecca. “Postmodern…Postmuseum: New Directions in Contemporary Museological Critique.” Museological Review 1.1 (1994): 1-13. Print.

ERI (The English Research Institute). “Becoming for Beginners.” Deleuze Studies. Manchester Metropolitan University, 2005. Web. «http://www.eri.mmu.ac.uk/deleuze/on-deleuze-why_study_Deleuze.php». Accessed 14 July, 2010.

Falk, John H. and Lynn D. Dierking. The Museum Experience. Washington D.C.: Whalesback, 1992. Print.

Fosnot, Catherine T., ed. Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives, and Practice. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1996. Print.

Girl Museum. Web. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/». Accessed 18 July, 2010.

—. “Across Time &Space” Exhibition. Web. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/AcrossTimeSpace/index.htm». Accessed 12 July 2010.

—. “Defining Our “Exhibition. Web. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/DefiningOurTerms/». Accessed 13 July, 2010.

—. “Heroines Quilt” «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/HeroineQuilt/index.htm». Accessed 13 July, 2010.

Grosz, Elizabeth, ed. Space, Time and Perversion. New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

—. “Bergson, Deleuze and Becoming (44).” 2005. Web. «http://www.uq.edu.au/~uqmlacaz/ElizabethGrosz%27stalk16.3.05.htm». Accessed 18 July 2010.

Heckman, Davin. “‘Gotta Catch ’em All’: Capitalism, the War Machine, and the Pokémon “Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge5 (2002). Web. «http://www.rhizomes.net/issue5/poke/pokemon.html». Accessed 10 July, 2010.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eileen. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London: Routledge, 1991. Print.

Institute of Humanities & Social Science Research. “Deleuze Studies.” Manchester Metropolitan University, 2011. Web. «http://www.hssr.mmu.ac.uk/deleuze-studies/». Accessed 25 April, 2011.

Kennicott, Philip. “Ralph Appelbaum’s Transformation of The Museum World Is Clearly Evident.” Washington Post, March 29, 2009. Web. «http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/26/AR2009032604470.html». Accessed 11 July, 2010.

Mayer, Carol E. “‘We Have These Ways of Seeing…’- A Study of Objects in Differing Realities.” Museological Review 1.1 (1994): 31-41. Print.

Merriam-Webster Online. “Girl.” Web. «http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/girl». Accessed 25 April, 2011.

“Parents: Cyber Bullying Led to Teen’s Suicide.” ABC News, November 19, 2007. Web. «http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3882520&page=1». Accessed 10 May, 2011.

Roffe, Jon. “Gilles Deleuze (1925 – 1995)”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2005. Web. «http://www.iep.utm.edu/deleuze». Accessed 18 July 2010.

Snow, Gordon M. “Statement before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security.” The FBI’s Efforts to Combat Cyber . FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), 2010. Web. «http://www.fbi.gov/news/testimony/the-fbi2019s-efforts-to-combat-cyber-crime-on-social-networking-sites». Accessed 11 May, 2011.

Stivale, Charles J., ed. Gilles Deleuze: Key Concepts. Montreal: McGill-Queens University, 2005. Print.

Tacoma Art Museum. “Open Art Studio.” 2011. Web. «www.tacomaartmuseum.org/Page.aspx?nid=204». Accessed 27 April, 2011.

Wilkerson, Richard C. Deleuzian Difference and Non-Representational Dreamwork. San Francisco: DreamGate, 2004. Print.

Notes

[1] Nineteen-year-old Chaya Abramov’s Portrait-Self was created in the style of notan, the Japanese design concept of two-dimensional interplay between light and dark. The distinction between the simple and complicated forms created by the pencil and scissor using the contrasting white, grey, and black paper construct a portrait that becomes a metaphor for the polarities of identity. Abramov further explores this dialectic in an upcoming Girl Museum exhibition of multimedia girl portraits.

[2] Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1987, p. 277.

[3] Girl Museum. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/». Accessed 18 July, 2010.

[4] Falk and Dierking examined this concept in The Museum Experience. Washington D.C.: Whalesback, 1992.

[5] ERI (The English Research Institute). “Becoming for Beginners.” Deleuze Studies. Manchester Metropolitan University, 2005. «http://www.eri.mmu.ac.uk/deleuze/on-deleuze-why_study_Deleuze.php». Accessed 14 July, 2010. Now the Institute of Humanities & Social Science Research “Deleuze Studies.” «http://www.hssr.mmu.ac.uk/deleuze-studies/». Accessed 25

[6] Girl Museum. “Across &Space” Exhibition. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/AcrossTimeSpace/index.htm». Accessed 12 July, 2010.

[7] Roffe, Jon. “Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995).” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2005. «http://www.iep.utm.edu/deleuze».

[8] Hooper-Greenhill, Eileen. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London: Routledge, 1991, p. 5.

[9] Heckman, Davin. “‘Gotta Catch ’em All’: Capitalism, the War Machine, and the Pokémon Trainer.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge 5 (2002). «http://www.rhizomes.net/issue5/poke/glossary.html».

[10] Girl Museum. “Defining Our Terms” Exhibition. http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/DefiningOurTerms/DefiningOurTermsArtofGirlhood.html. Accessed 13 July, 2010.

[11] With apologies to Deleuze and Guattari, in this particular instance the more traditional definition of girl as “a female child from birth to “is being used. Merriam-Webster Online. «http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/girl». Accessed 25 April, 2011.

[12] Deleuze and Guattari, p. 479.

[13] Girl Museum. “Heroines “Exhibition. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/HeroineQuilt/index.htm». Accessed 13 July, 2010.

[14] Ibid. Accessed 25 April, 2011.

[15] Ibid. Accessed 25 April, 2011.

[16] Stivale, Charles J., ed. Gilles Deleuze: Key Concepts. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2005, p. 126.

[17] Girl Museum. “Defining “Exhibition. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/DefiningOurTerms/index.html». Accessed 26 April, 2011.

[18] Ibid.«http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/DefiningOurTerms/DefiningOurTermsGirlDefined.html». Accessed 13 July, 2010.

[19] Deleuze and Guattari cite Remy Chauvin: “the aparallel evolution of two beings that have absolutely nothing to do with each other.” Deleuze and Guattari, p. 10.

[20] Girl Museum. “Defining “Exhibition. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/DefiningOurTerms/DefiningOurTermsGirlDefined.html». Accessed 13 July, 2010.

[21] Ibid.«http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/DefiningOurTerms/DefiningOurTermsMuseumDefined.html». Accessed 13 July, 2010.

[22] Deleuze and Guattari, p. 277.

[23] The “GirlSpeak” exhibition series exists specifically for this reason, though some traditional museums have similar spaces. Tacoma Art Museum’s Open Art Studio allows visitors to create their own artistic works, either projects based on current museum exhibitions or using the art supplies in whatever way inspires. These objects are then, if the visitor/artist so desires, left on display for other visitors. Tacoma Art Museum. “Open “«www.tacomaartmuseum.org/Page.aspx?nid=204». Accessed 27 April, 2011.

[24] Heckman, Davin. “‘Gotta Catch ’em All’: Capitalism, the War Machine, and the Pokémon Trainer.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge 5 «http://www.rhizomes.net/issue5/poke/glossary.html». Accessed 15 July, 2010.

[25] Ibid. Accessed 26 April, 2011.

[26] Stivale, p. 101.

[27] Deleuze & Guattari, p. 242.

[28] Girl Museum was founded in Spring 2009, making it just over two years old at the time of publication.

[29] Snow, Gordon M. “Statement before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security.” The FBI’s Efforts to Combat Cyber Crime on Social Networking Sites. FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), 2010. «http://www.fbi.gov/news/testimony/the-fbi2019s-efforts-to-combat-cyber-crime-on-social-networking-sites». Accessed 11

[30] “Parents: Cyber Bullying Led to Teen’s Suicide.” ABC News, 2007. «http://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3882520&page=1». Accessed 10

[31] Brunker, Mike. “‘Sexting’ Surprise: Teens Face Child Porn Charges.” MSNBC.com, 2009. «http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28679588/ns/technology_and_science-tech_and_gadgets/t/sexting-surprise-teens-face-child-porn-charges/». Accessed 10 May, 2011.

[32] Doyle, Denise. “Art and the Avatar: The Kritical Works in SL Project.” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 4.2-3 (2008), pp. 137-153.

[33] Girl Museum. “Across Time & Space” Exhibition. «http://www.girlmuseum.org/exhibitions/AcrossTimeSpace/index.htm». Accessed 12 July, 2010.

[34] Ibid. Accessed 12 July, 2010.

[35] Grosz, Elizabeth. “Bergson, Deleuze and Becoming “2005. «http://www.uq.edu.au/~uqmlacaz/ElizabethGrosz%27stalk16.3.05.htm». Accessed 16 July, 2010.

[36] Fosnot, Catherine T., ed. Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives, and Practice. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1996, p. 23.

[37] Girl Museum. “About Us.” «http://www.girlmuseum.org/about». Accessed 27 April, 2011.

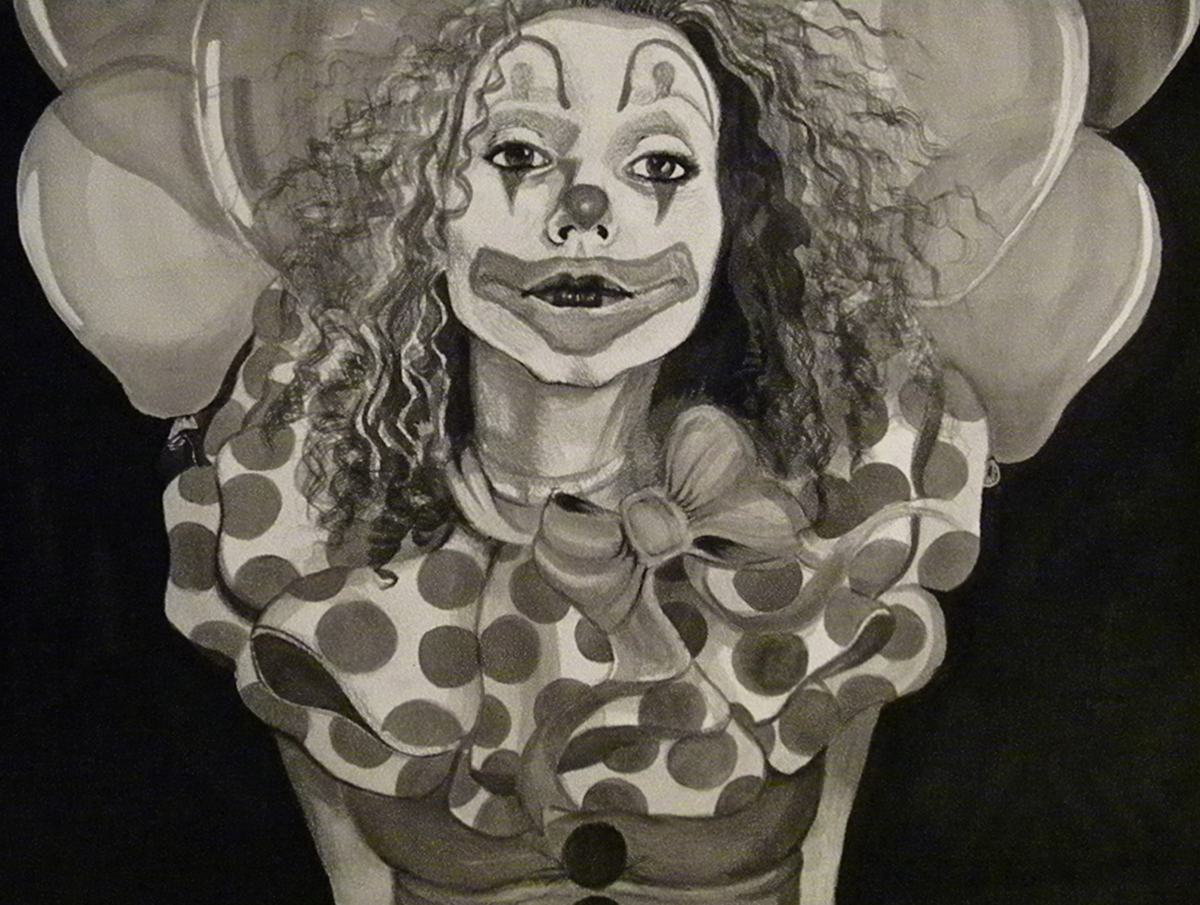

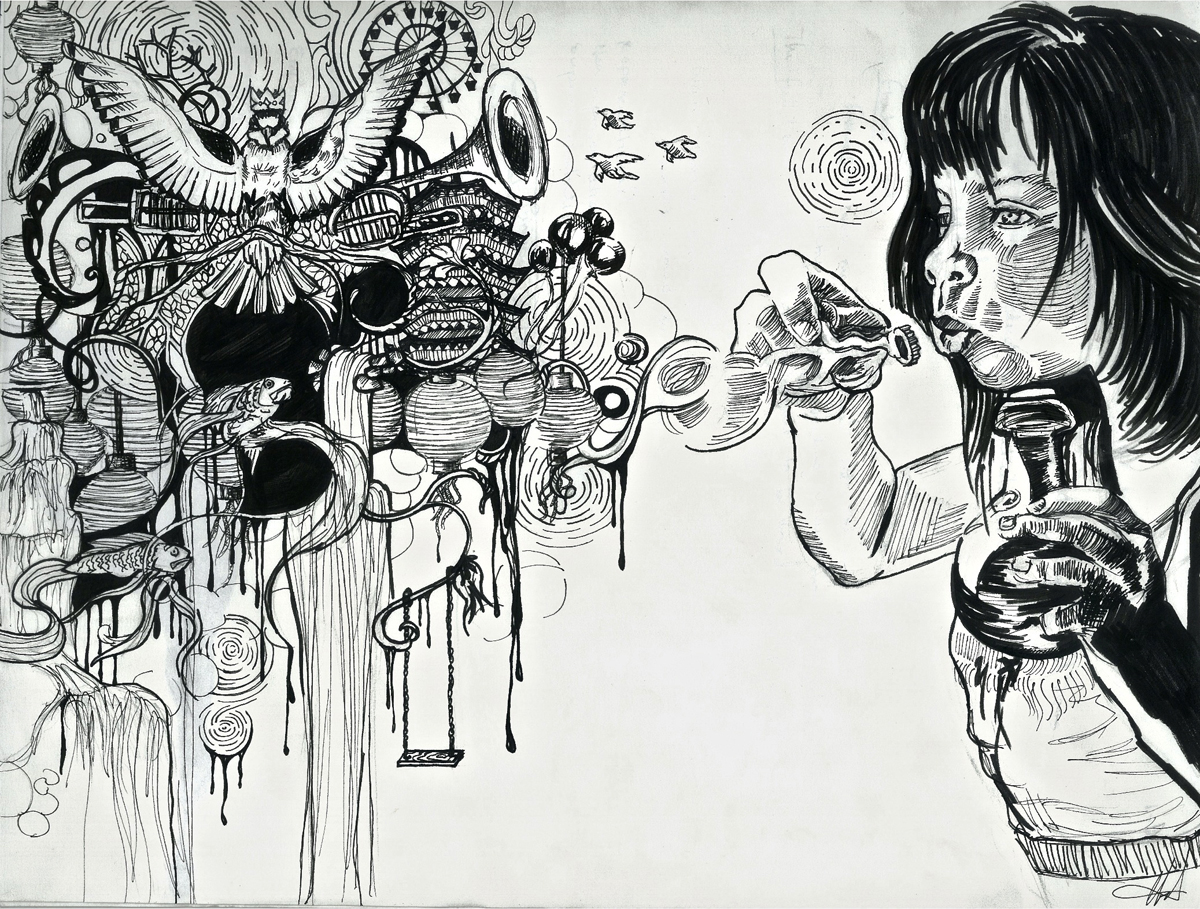

Chaya Avramov

Within this essay was a selection of images illustrative of our work, including Chaya’s Self-Portrait. This young artist explores the construction of girlhood and girl culture through a range of media.

Beauty, joy, and complexity shine through Chaya’s eloquence and skillfully crafted faces. Her girls are adventurous, humorous and unique.

View Chaya’s works exploring girls and girlhood below and visit her shop if you want to find more.

Child’s Town by Chaya Av

Imagination of Childhood/Child’s Town, micron pen on drawing paper, 11″ x 14″, 2011.

Subliminal Arrangements by Chaya Av

Subliminal Arrangements, mixed media on watercolor paper, 22″ x 30″, 2011.

![Lady with an Ermine, charcoal [vine and compressed] on Strathmore, 22" x 30", 2011.](https://www.girlmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/8-LadywithErmine.jpg)