Myth: Girls’ literature is historically limited to the realm of the diary.

Fact: Girls have led many major moments in literary history, including some of the world’s oldest poetry, the first Black poet in America, and the earliest writers of science fiction.

Girl Authors explores the literary depth and creativity of girls throughout history. We also explore the issues surrounding girl authors – from determining their ages to ensuring their works are preserved for future generations.

Why are Girls Overlooked or Hard to Find?

There are many reasons why young girls – or the girlhoods of famous female authors – are overlooked in literary history and scholarly analysis. In this section, we use specific examples to explore different reasons why girls have been overlooked in studies of literature – and what these reasons reveal about the nature of girlhood.

The Problem of Ignorance

For many female authors, girlhood was a formative period for their later success. Well-known women such as Jane Austen were prolific writers in their youth, but often these youthful writings are relegated to manuscript collections, posthumous publications, or simply forgotten. To ignore youthful writing is to ignore the formative period of female authors – many of whom utilized their pens to pursue lives beyond societal norms and expectations.

Jane Austen (1775-1815) is a case study in this ignorance. During her lifetime, Jane’s success was limited. She published anonymously during the last decade of her life, but her authorship soon became an open secret. While her novels were fashionable, they were largely ignored until the 1830s – nearly twenty years after Jane’s death. Her earlier works – now called Juvenilia – were primarily written to amuse her family. Written from ages 11 to 17, these compiled works are what scholar Janet Todd called stories “full of anarchic fantasies of female power, license, illicit behavior, and general high spirits”. From ages 18 to 20, Jane wrote Lady Susan, a novella told through letters. These works were not published until the 1870s – sixty years after Jane’s death.

So why are these youthful works integral to understanding Jane’s later works? As Freya Johnston explains in Jane Austen, Early and Late (2021):

“These frantic mini-novels reveal Austen using the best-selling fiction of her day to train herself in the parts and rules of novel writing. She repeatedly asks herself, and us, whether characters have to be believable in order to be compelling. Do their actions need reasons and explanations? How unhinged, inexplicable, or random is fiction permitted to be? How far can a reader be pushed?”

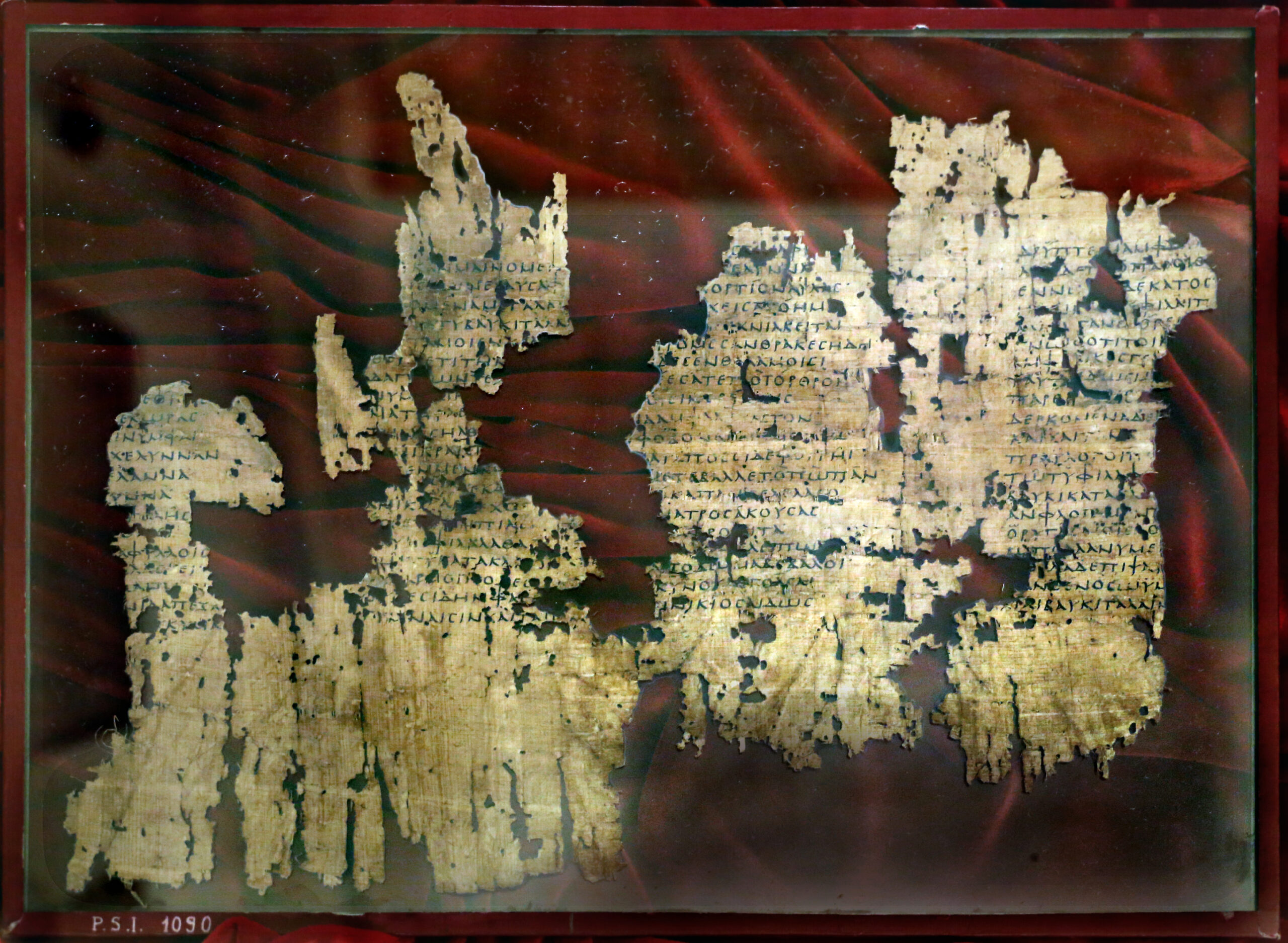

For some female authors, we do not know if their literary accomplishments occurred during or after girlhood. This is especially true in pre-modern time periods, when age was not recorded so much as name and gender. One example is Female Troubadours. In the below episode of GirlSpeak, Tiffany explores the incredible – yet fragmentary – works of female troubadours in the Medieval period:

Female Troubadours Script

Curious to know what that was? It is a poem by the Comtesse de Dia, who was a female troubadour – known as a trobairitz – and lived around 1140 C.E.. The poem translates into English as:

Of things I’d rather keep in silence I must sing:

So bitter do I feel toward him

Whom I love more than anything.

With him my mercy and fine manners are in vain,

My beauty, virtue, and intelligence.

For I’ve been tricked and cheated

As if I were completely loathsome.

There’s one thing, though, that brings me recompense:

I’ve never wronged you under any circumstance,

And I love you more than Seguin loved Valensa.

At least in love I have my victory,

Since I surpass the worthiest of men.

With me you always act so cold,

But with everyone else you’re so charming.

I have good reason to lament

When I feel your heart turn adamant

Toward me, friend; it’s not right another love

Take you away from me, no matter what she says.

Remember how it was with us in the beginning

Of our love! May God not bring to pass

That I should be the one to bring it to an end.

The great renown that in your heart resides

And your great worth disquiet me,

For there’s no woman near or far

Who wouldn’t fall for you if love were on her mind.

But you, my friend, should have the acumen

To tell which one stands out above the rest.

And don’t forget the stanzas we exchanged.

My worth and noble birth should have some weight,

My beauty and especially my noble thoughts;

So I send you, there on your estate,

This song as messenger and delegate.

I want to know, my handsome noble friend,

Why I deserve so savage and so cruel a fate.

I can’t tell whether it’s pride or malice you intend.

But above all, messenger, make him comprehend

That too much pride has undone many men.

I was introduced to this poem, and others like it by female troubadours, in the book, The Women Troubadours by Meg Bogin. Like many others, I thought that troubadours were only men, and was delightfully surprised to find out about the trobairitz through Meg’s work, which was the first full-length book on the subject.

The troubadours and trobairitz were medieval singer-poets who typically hailed from the south of France. They flourished during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, thought only a handful of their works – which include poems and dialogues set to music – have been translated and study. The only study of female troubadours prior to Meg’s work dates to 1888.

The troubadours were among the first to express what we know as “romantic love” – a love and affinity that is distinct from sexual passion. As Meg recounts, to the troubadours, “Love was proclaimed the supreme experience of life, and the quest for love, with the lady as its guiding spirit, became the major theme of Western literature” due to their influence.

Most of the poems written by troubadours were addressed to women of the high nobility – for example, a queen, duchess, or lady. Often, the troubadour was in pursuit of the lady. These poems talked about the troubadour’s quest for his lady’s love and admiration. In exchange, he pledge his eternal loyalty and obedience to her.

Through his obedience, the troubadour hoped to gain favor – including patronage, gifts, and widespread acclaim as a master of his poetic craft. You may be familiar with a concept that was actually derived from this – ever heard of chivalry? You can thank the troubadours for it. The entire concept of a knight seeking the love and patronage of a lady is based on the troubadours’ own journeys for it.

Troubadour poetry was also one of the first times that a vernacular – or common – language was given equal status to literary languages. The movement as a whole spurred the development of poetry in other common languages, and had a profound influence on Western relationships and thought even into the present day.

The troubadours and trobairitz were fascinating for many reasons. The troubadour movement – with its emphasis on women holding the reigns of power in relationships and patronage – was in direct contrast to women’s real-life status. Most medieval women were the property and pawns of men, seen only as wives, keepers of the household, and breeders of sons. Their success in life was wholly measured on the fulfillment of their role as wife and mother. It was a time of misogyny on a widespread, and almost institutionalized, scale.

So why did the troubadours praise women and elevate them into positions of power? No one really knows for sure, but scholars have put forth many theories.

It could stem from the fact that the south of France – where troubadours originated – was less strict in its fulfillment of gender norms in the medieval periods. This region’s laws and customs were more favorable to women as a whole, having held on to old Roman codices and Celtic and Visigoth practices that had been favorable to women. You can think of the south of France during the medieval period as kind of a melting pot – a lot of different groups had come and gone from the region, and each had left its indelible mark on southern French culture. Part of this was codes, laws, and norms that made women slightly more powerful and respected than their counterparts in other regions of Europe. That isn’t to say women were more equal to men – it’s just that they had a bit more agency in their daily lives.

Another reason might be that, during the early twelfth century, there was a boom in new agricultural techniques, leading to a population increase. And this increase in population led to many things, including the flourishing of culture, scholarship, building, and trade. Combined with the Crusades to the Middle East and parts of northern Africa, this was a time when a lot of cultures were meeting, mixing, and blending together. There was a lot of trade in ideas, and the south of France – being where many Crusaders left to sail to the Middle East – was one of the primary centers for this type of cross-cultural trade. Troubadour poetry itself might be a product of this trade, as it is remarkably similar to the poetry of Andalusia and Arabia, where Arab poets had been worshipping their ladies for at least two hundred years prior.

However, the Crusades also led to a drastic decrease in the male population of Europe. As men went off to and died in war, women were left in charge of their lands and holdings, and this was especially pronounced in the south of France where old customs meant that women were traditionally given control of property upon their fathers’ or husbands’ death.

In truth, it’s probably a mix of all these factors that led to the rise of troubadours and trobairitz. The south of France happened to be the right place, at the right time, for such poetry and the exaltation of women to emerge. Some scholars have even called it an “expression of a deep psychological need left unmet by the unrelenting masculinity of feudal culture” and the Crusades. Fair enough.

Yet the most pronounced factor – and the one that likely led to the rise of female troubadours – might have something to do with the troubadour movement itself. The first troubadour was Guilhem de Poitou (GEE-YEM de Pwa-two), whose songs were written to amuse his court in northern Occitania. His songs exalted obedience to women as a pathway to mystic joy – an almost religious experience that would come to be called “fine love” or “courtly love”. His writings quickly evolved from mere poems and songs into a complex code of love that we know as chivalry.

In all of it, Guilhem’s model was the lady – typically, the wife of his employer and the most powerful woman of the court. Thus, troubadour idolatry gave ladies of the high nobility even more power than they already held by law and custom. This could have spurred the trobairitz to start their own practice, taking the power troubadours had given them in order to finally express themselves as women publicly and in a manner that is almost a response to the men who claim to adore them. It was a way for women to express their desires and needs in a socially acceptable performance.

It is one of the first times we have female witnesses from the medieval period who tell us their stories in their own voices. There are very few sources directly from women otherwise, and the subject matter of the trobairitz is very distinct from their male counterparts. They are exceptional in musical history as the first known female composers of Western secular music – all earlier known female composers wrote sacred music – and exceptional in history itself as being female voices completely unedited by male hands.

Of all the troubadours, we know that about twenty were women, and all of them hailed from the south of France in a region known as Occitania. They were all from the high nobility, wives or daughters of the lords of Occitania, and likely knew male troubadours as family members, friends, or members of their courts. Even more so, at least a third of the trobaritz were patrons of troubadours themselves.

Almost all information which exists about the trobaritz come from their vidas (biographies) and razós (contextual explanations of the songs), the brief descriptions that were assembled in song collections called chansonniers.

The first female troubadour was Tibors, the sister of the troubadour Raimbaut d’Orange and the wife of Bertrand de Baux. She lived around 1130 CE. Only a fragment of one of her poems survives, and it reads:

Sweet handsome friend, I can tell you truly

That I’ve never been without desire

Since it pleased you that I have you as my courtly lover;

Nor did a time ever arrive, sweet handsome friend,

When I didn’t want to see you often;

Nor did I ever feel regret,

Nor did it ever come to pass, if you went off angry,

That I felt joy until you had come back

Even more curiouser than the fact there were trobairitz is the subject matter they addressed. The trobaritz wrote about love, but in very different terms from their male counterparts. They often preferred the more straight-forward speech of conversation (as opposed to rhyming) and wrote about relationships that we recognize almost immediately.

One example is this excerpt from a poem by the trobaritz Castelloza, born around 1200 C.E., in Auvergne. She was likely a noblewoman whose husband fought in the Fourth Crusade. It reads:

You stayed a long time, friend,

And then you left me,

And it’s a hard, cruel thing you’ve done;

For you promised and you swore

That as long as you lived

I’d be your only lady:

If now another has your love

You’ve slain me and betrayed me,

For in you lay all my hopes

Of being loved without deceit.

Handsome friend, as a lover true

I loved you, for you pleased me,

But now I see I was a fool,

For I’ve barely seen you since.

I never tried to trick you,

Yet you returned me bad for good;

I love you so, without regret,

But love has stung me with such force

I think no good can possibly

Be mine unless you say you love me.

As we can see from Castelloza’s poem, the trobaritz wrote as women – in a direct, unambiguous, highly personal language like that of a journal or conversation. This shows us that they wrote for personal, not professional, reasons.

It also demonstrates that love occupied a central place in women’s emotional lives. There might have even been lesbian love, as demonstrated in this poem by Bieiries de Romans from around the first half of the 13th century. It reads:

Lady Maria, in you merit and distinction,

Joy, intelligence and perfect beauty,

Hospitality and honor and distinction,

Your noble speech and pleasing company,

Your sweet face and merry disposition,

The sweet look and loving expression

That exist in you without pretension

Cause me to turn toward you with a pure heart.

Thus I pray you, if it please you that true love

And celebration and sweet humility

Should bring me such relief with you,

If it please you, lovely woman, then give me

that which most hope and joy promises

For in you lie my desire and my heart

And from you stems all my happiness,

And because of you I’m often sighing.

And because merit and beauty raise you high

Above all others (for none surpasses you),

I pray you, please, by this which does you honor,

Don’t grant your love to a deceitful suitor.

Lovely woman, whom joy and noble speech uplift,

And merit, to you my stanzas go,

For in you are gaiety and happiness,

And all good things one could ask of a woman.

Whatever their intentions, it is clear that the poetry and songs of the trobaritz were as varied and complex as the women who wrote them. Despite their variety, all the trobaritz wrote about two things: first, to be acknowledged for who they are as women and as individuals, and second, to have a determining voice in their lives and relationships. As Meg Bogin stated, “The voices of the women troubadours are as complicated as the voices of real people, and as earth-bound. They sound like women any of us could know. Unlike the men, who often wrote in the persona of the knight, the women wrote in no one’s character but their own.”

Unfortunately, the troubadours and trobaritz did not last long. In 1209, Pope Innocent III proclaimed a crusade against the “heretics” of Occitania, known as the Albigensian Crusade, which targeted the troubadours and their courts of love. Within fifty years, the great cities and centers of the troubadour movement lied in ruins. Women had lost their rights – both in poems and songs as well as law and custom – and fell into a status more in line with the rest of European women of the time. Troubadour poetry, the ultimate symbol of the southern French way of life, had been the first casualty – the troubadours were forced into silence or exile, and the women they so adored had been silenced forever.

It is only through the work of scholars like Meg Bogin, and other medievalists, that we know the trobaritz lived, loved, and – ultimately – sought a better world for women much the same as we do today.

Other examples come from across the globe. Hrotsvitha (c. 935-973) was a member of a German religious community who set many firsts: the first female poet and writer from German-speaking lands and the first female historian. However, we do not know her exact birthdate or where she came from. We know that she lived and studied at Gandersheim Abbey, where she learned to read and write – likely experimenting with her own literary talents. Discovered and encouraged by the abbess, Hrotsvitha wrote legends, comedies, poetry, and plays beginning in the 950s (when she was about 20 years old). Her works were “lost” until the early 1600s, when a man “rediscovered” and edited them for publication. This male gaze lasted until the 1970s, when women’s history scholars reinterpreted them from a female perspective. Hrotsvitha illustrates several problems: the lack of clear birth dates and lineage to determine age, the isolation imposed living in an abbey (which also granted independence to write), and the reinterpretation by men that lasted for centuries.

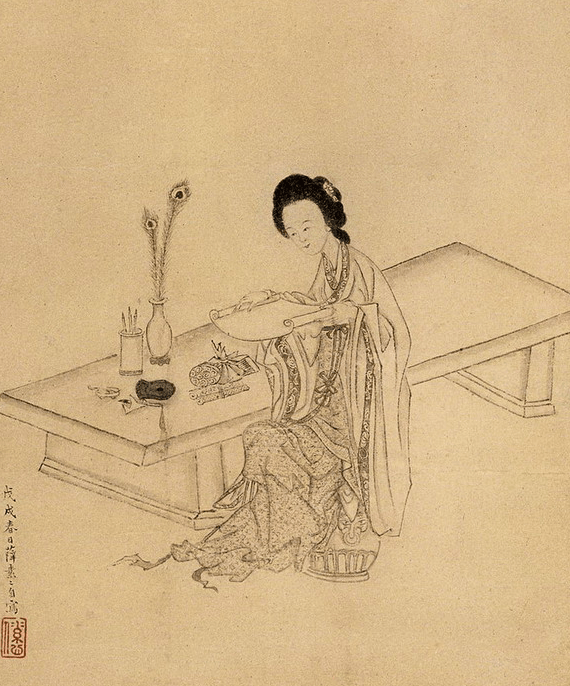

Another problem – that of not knowing when during her lifetime works were published – is illustrated by Xue Susu (c. 1564-1650?). A courtesan during the Ming dynasty in China, Xue Susu was an accomplished poet, painter, and archer. While her paintings are now held by many museums, her poetry is largely confined to accompanying her paintings or lost to time; only one extant volume survives. These poems were read at literary gatherings and traded throughout Ming dynasty literary circles, hence ensuring their partial survival. Unfortunately, none of her works are dated – so we do not know when she wrote or painted them, though her celebrity status by the 1580s indicates that she must have been painting and writing as a girl.

The Problem of Preservation

Being a girl author is also more than the words published on pages. It encompasses a wide range of issues in girl studies, including how archives collect and preserve their works. Like many other facets of girlhood, museums and archives have simply not prioritized these for preservation and digitization.

Additionally, some girl authors did not write their works. Rather, their literary creations were passed down through oral tradition. Many non-Western cultures are based in oral traditions, which academic patriarchy has traditionally ignored. The works of Habba Khatoon (1554-1609) demonstrate this problem. Born in what is now Jammu and Kashmir, Habba was a Kashmiri Muslim poet who learned to write from her village’s moulvi (religious scholar). At age 16, she was married to the emperor of Kashmir (who liked her singing voice). Nine years later, her husband was imprisoned and Habba became an wandering ascetic, singing songs of her own invention. Today, she is hailed as the last independent poet queen of Kashmir and her songs are still popular throughout the region. Yet, these songs have – until recently – largely remained in the oral tradition, hence their lack of preservation.

Luckily, the problem of preservation is beginning to change. As the interviews with archivists below illustrate, institutions and academia are beginning to recognize the need to preserve authors’ youthful writings and especially the writings of young females.

Phillis Wheatley with Carrie Hintz

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Phillis...

Mary Shelley with Elizabeth C. Denlinger

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Mary Shelley...

Louisa May Alcott with Christine Jacobson

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Louise May...

Emma Lazarus with Melanie Myers

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Emma Lazarus...

Edith Nesbit with McFarlin Library

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Edith Nesbit...

Frances Hodgson Burnett with Laura Romans

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Frances...

Maureen Daly Papers with Linda J. Long

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Maureen Daly...

Margaret Mitchell with Serena McCracken

How do archives collect girl authors? In this interview series, we welcome curators and archivists to share how their institutions collect and utilize materials by girls who were or became published authors in their youth. Today, we look at the papers of Margaret...

Girl Authors in Herstory

So who are the girl authors we know and love? Who has been overlooked? The timeline below explores girl authors in the historical and recent past, including links to their works so that you can read their writings!

Erinna

6th century BCE

Erinna was 19 years old when she wrote Distaff, a lament for her friend, Baucis. In it, Erinna recalls memories of her and Baucis’ childhood, including the games they played together. Influenced by both Homer and Sappho, Erinna uses the juxtaposed themes of remembrance and forgetfulness, along with a feminist lens, to deliver a beautiful homage to not just her friend, but also her youth.

Read her work here.

Li Qingzhao

Song dynasty, China

A poet and essayist, Li Qingzhao grew up well-educated among China’s elite. She and her husband were both art collectors and interested in epigraphy, which would often inspire many of the love poems they would write to each other. Qingzhao’s other works are largely derived from her own life experience. Her earlier poems depict her life among the elite and have a lighter tone compared to her later works, which reflect the struggles she endured upon fleeing her home and the death of her husband. She is considered to be one of China’s greatest poets.

Read her work here.

Habba Khatoon

circa 1580

Habba Khatoon, also known as The Nightingale of Kashmir, was a Muslim poet and singer. Born a peasant, she later drew the attention of Kashmir’s last emperor, Yousuf Shah Chak, and became his queen consort. There are no written records of Khatoon’s work as it is steeped in oral tradition, but others have recorded pieces of her songs and continue to sing them today. Many of her songs convey a sense of longing and separation, spurred by the imprisonment of her husband and later, his death. She spent the rest of her life after the loss of her husband as an ascetic.

Read her work here.

Heo Nanseolheon

1571

Heo Nanseolheon was a Korean artist and poet. She grew up during the mid-Joseon dynasty in a traditional Confucian and conservative household. Her talents were largely overlooked until her brother introduced her to literature and began actively tutoring her. In 1571, at the age of 8, Nanseolheon wrote a series of poems entitled Inscriptions on the Ridge Pole of the White Jade Pavilion in the Kwanghan Palace. These poems were heavily influenced by Tang poetry and contained many naturalistic elements. Upon her loveless marriage, Nanseolheon’s poetry adopted a more lamentful style that spoke to the sufferings of married women and included more emotive language than her previous works.

Read her work here.

Xue Susu

Ming Dynasty

Xue Susu was a Chinese artist and poet who lived during the Ming Dynasty. Well-known amongst the elite of Eastern China and Beijing, Xue Susu also worked as a courtesan and was also recognized for her skills in mounted archery. Her paintings and their corresponding poems are housed in museums world-wide and were influenced by the Buddhist religion. Susu’s figure paintings are amongst her most popular. Even after her conversion to Buddhism in her later years, Susu continued to immerse herself in the world of literature and art, as well as entertain influential individuals within those respective fields.

Read her work here.

Katherine Philips

mid-1600s

Katherine Philips was a London-born poet and translator. She was educated at a boarding school in Hackney where she first founded The Society of Friendship, an organization intent on highlighting female friendship, literature and women writers. Fluent in several languages, she is renowned for her translation of Pierre Corneille’s Pompee and Horace, as well as her collection of poetry entitled Poems by the Most Deservedly Admired Mrs. Katherine Philips, the Matchless Orinda, that was published posthumously upon her death from smallpox in 1664.

Read her work here.

Catharina Questiers

mid-1600s

An Amsterdam native, Catharina Questiers was a Dutch poet and playwright well known during the mid to late 17th century. She grew up in a creative household and took after her father who was active and renown in the realm of theater and the arts. At just eight years old, Catharina wrote her first poem and continued to hone her craft upon her publication in Corpse’s Complaint. She went on to pen several plays modeled after Spanish prose as well as additional poems both solo and in collaboration with others, including her friend Cornelia van der Veer. She died in 1669 of natural causes.

Read her work here.

Juana Ines de la Cruz

mid-1600s

Revered as a significant hispanic literary figure, Juana Ines de la Cruz was a nun, scholar, and Latin American poet during the mid 17th century. She was also a groundbreaking femenist writer who paved the way for other women, especially latinas, to pursue creative outlets and education. Her plays and poetry were often considered controversial for the way they pushed back against traditional gender roles and advocated for women’s rights. Inspired by Spanish Golden Age themes, she wrote many poems, plays, and essays in a variety of different styles.

Read her work here.

Lucy Terry Prince

1740s

Lucy Terry Prince was an enslaved African who was likely born in the 1730s. In 1746, Lucy heard of two white families ambushed by Native Americans in Deerfield – an area known as “the Bars.” Lucy composed the ballad “Bars Fight” to commemorate the slain men and women. She won local acclaim, and is believed to have continued writing poetry. Only “Bars Fight” has survived to the present day, making her the first known African American writer.

Read her work here.

Hannah More

1760s

In 1762, at the age of sixteen, Hannah More wrote The Search for Happiness – a play which sold over 10,000 copies within the next twenty years. The daughter of a schoolmaster who moved frequently, Hannah’s experiences with a variety of people from different economic and religious backgrounds inspired her work. Hannah became a well-known writer in London, and used her voice to advocate against slavery and sexism. She and her sister, Martha, founded 12 schools for poor children and numerous social clubs for women.

Read her work here.

Phillis Wheatley

1770s

Phillis Wheatley was born in Senegal or Sierra Leone, where she was captured and enslaved by white traders. Purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, Phillis was tutored alongside the Wheatley’s children in English, Latin, history, geography, and the Bible. Phillis wrote her first poem at the age of 11, and a year later began publishing in local newspapers. Her poems became popular, and were eventually published as Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in 1773. Despite her fame, all of Phillis’s earnings were kept by the Wheatley family – even after Phillis was emancipated. Even though Phillis continued writing poetry, her writing was rarely published and eventually lost.

Read her work here.

Mary Shelley

1818

Mary Shelley was born in 1797, the daughter of writer Mary Wollstonecraft. At the age of 18, while staying in Switzerland with her new husband (Percy Shelley) and Lord Byron, Mary conceived the first science fiction novel: Frankenstein. Sitting around a fire on a rainy night, Lord Byron challenged each member of their party to write a ghost story. For Mary, the result was Frankenstein. She explained that the story was inspired by a nightmare, and the weeks following that night saw her frantically put pen to paper. Frankenstein was published in 1818, when Mary was 20 years old.

Read her work here.

Elizabeth Browning

1826

Elizabeth Browning was an English poet who was active in the Victorian era. When she was young, she preferred immersing herself in books, rather than attending social events. In 1817, 11-year-old Elizabeth wrote her first Homeric epic, The Battle of Marathon: A Poem. Nine years later, Elizabeth anonymously published her first collection of poems, An Essay on Mind with Other Poems. In her collection, Elizabeth reflected and explored her fascination with Byron and Greek politics. She later called this book “a girl’s exercise, nothing more nor less”.

Read her work here.

Louisa May Alcott

1849

Long before becoming an accomplished author with Little Women, Louisa May Alcott knocked at the door of the literature world with The Inheritance in 1849. Although times were desperate for 17-year-old Lousia and her family when the book was written, the novel is a sentimental, romantic story about love and virtue. The manuscript was not discovered and published until 1997. The Inheritance offered readers an interesting look at the forces that foreshadowed Louisa’s later work.

Read her work here.

Emma Lazarus

1866

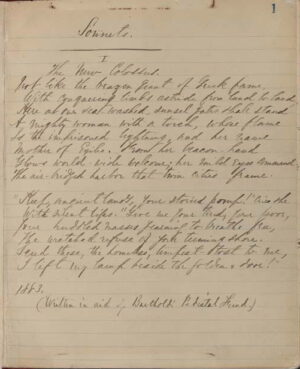

Emma Lazarus grew up in New York City in a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. Privately tutored, Emma studied mythology, literature, poetry, music, Classics, and several languages. She likely began composing poetry at age 11, with highly romantic poems of gods and heroines. She published her first book, Poems and Translations Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Seventeen in 1866, containing thirty poems and forty-five translations of French and German authors. Five years later, Emma’s anthology Admetus and Other Poems (1871) launched her to literary stardom. In particular, her poem, “The New Colossus,” was utilized at the base of the Statue of Liberty, where it still stands inscribed today.

Read her work here.

Daisy Ashford

1885

Born in 1881, Daisy Ashford loved creating stories. At age four, she dictated The Life of Father McSwiney and, as she grew, wrote several short stories, plays, and novellas. At age 9, Daisy wrote The Young Visiters, a novella about upper-class society in 19th century England. Rediscovered by Daisy’s daughter in 1919, The Young Visiters was soon published almost exactly as it was written, with an introduction by J.M. Barrie. It was an immediate success, going through eight printings in its first year and later becoming a stage play, musical, 1984 feature film, and 2003 television series.

Read her work here.

Marjorie Bowen

1901

Born in 1885, Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long wrote under many pen names in her lifelong writing career. She used the pseudonym Marjorie Bowen when she wrote her first fiction, The Viper of Milan, at age 16. The novel is set in medieval Italy and tells a story about the relentless rivalry in the aristocratic class. Before its eventual publication in 1906, The Viper of Milan was rejected by 11 publishers. They considered it inappropriate for a young woman to have written such a violent story. However, once published, the novel turned out to become a bestseller.

Read her work here.

Margaret Mitchell

1915

Many thought Margaret Mitchell only wrote only one novel during her lifetime, the famous Gone with the Wind published in 1936. But in 1915, 15-year-old Margaret had written a manuscript of a romance novella. The story is set in the South Pacific and the protagonists are (presumably) based on real people around Margaret. She gave the manuscript as a gift to a suitor named Henry Love Angel, who kept it along with Margaret’s letters to him until he passed away. Long after Margaret’s death, the manuscript was discovered and published along with a number of her girlhood writings, titled Lost Laysen.

Read her work here.

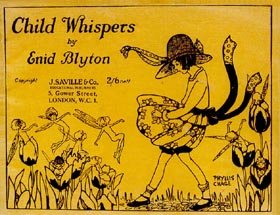

Enid Blyton

1916

Best known for her The Famous Five children’s book series, Enid Blyton was an English writer with an international reputation. Enid recalled that from an early age, she “liked making up stories better than [she] liked doing anything else”. She told stories to her brothers, kept a diary, and wrote letters to real and imaginary friends. In 1911, Enid entered a children’s poetry competition at age of 14. Although her mother disapproved of her efforts at writing and her manuscripts were rejected by publishers many times, Enid persevered. Her determination finally paid off in 1916, when her first poems were published in Nash’s Magazine.

Read her work here.

Hilda Conkling

1920

Born in 1910, American poet Hilda Conkling composed her entire body of poetic work between the ages of four and 14. She never wrote her poetry down herself. Rather, she spontaneously created the poems in conversation with her mother, and her mother transcribed them into written work. Hilda showed an almost unusual connection with nature in her poetry, although love for her mother and daydreams are also common themes in her work. Her first volume of poetry entitled Poems by a Little Girl was published in 1920. It was followed two years later by Shoes of the Wind and Silberhorn in 1924.

Read her work here.

Barbara Newhall Follett

1927

Born in 1914, Barbara Newhall Follett was an American novelist. Barbara began to write her own poetry by the age of four. Her stories and poems often concerned the natural world and the wilderness. Her first novel, The Adventures of Eepersip (later titled The House Without Windows) tells the story of a young girl who runs away from home and lives happily ever after in nature. Though her manuscript burned in a house fire in 1923, Barbara rewrote the entire story and published it in 1927. She published her next novel, The Voyage of the Norman D. in 1928. Barbara disappeared after leaving her apartment in 1939.

Read her work here.

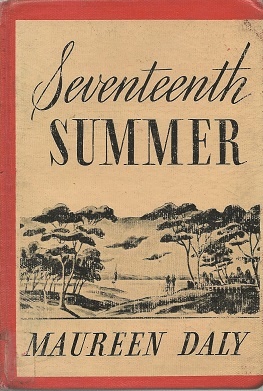

Maureen Daly

1942

Maureen Daly was born in Ireland in 1921. Her family moved to the US when Maureen was aged 2. Since age 15, Maureen had entered writing competitions and won multiple awards, including an O. Henry Award in 1938. She began writing her first novel, Seventeenth Summer, when she was 17. It took her several years to finish the manuscript. The book, about a 17-year-old girl’s romance story during one summer, was published in 1942. It instantly became a bestseller, attracting a large teenage audience.

Read her work here.

Pamela Brown

1941

Pamela Brown was a British writer. From an early age, she loved putting on plays with her friends. At age 13, Pamela started writing her first book when she was in high school, The Swish of the Curtain. The novel tells the story of seven children who form a theatre in a chapel, where they write, direct, and act their own plays. However, World War II broke out and she had to move back to Wales with her family. She managed to continue with her writing, and finally finished the book when she was 16. She later wrote four sequels to The Swish of the Curtain.

Read her work here.

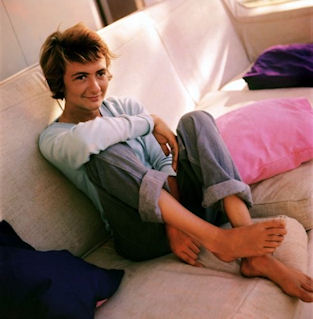

Francoise Sagan

1954

French writer Françoise Delphine Quoirez wrote under the name Francoise Sagan. Françoise was expelled from her Catholic schools several times, known as a rule-breaker since young. She published her first novel, Bonjour Tristesse (Hello Sadness) in 1954 at age 19, a story of a jealous, sophisticated schoolgirl’s summer romance. The story became an immediate international success. Françoise went on to produce numerous novels and playwrights in her long writing career, but Bonjour Tristesse has always remained her best-known work.

Read her work here.

Jane Gaskell

1957

Jane Gaskell was born in Lancaster, England in 1941. She wrote her first novel, Strange Evil, at age 14. The book was published in 1957, featuring a foreign, Gothic world full of claustrophobic conflicts and extraordinary fantasy. Strange Evil was acclaimed by many critics for its wild imagination. In 1958, Jane published her second novel, King’s Daughter. She went on to write numerous novels and series in the 1960s and 70s. Jane later became a professional astrologer.

Read her work here.

Minou Drouet

1957

Marie-Noëlle Drouet, known as Minou Drouet, was born in France in 1947. She published her first collection of poems, Arber, Mon Ami (Tree, My Friend) at age 10. The book sold more than 45,000 copies in the first few months after it was published, which also drew the suspicion of the public that Minou may not be the real author of her work. Minou agreed to take a test and write poems before witnesses. With a few lines that she wrote on the topic “Paris Sky”, she overcame the skepticism and earned membership in the French Society of Authors, Composers, and Music Publishers. Minou decided to become a nurse in 1966 and eventually left public life.

Read her work here.

S. E. Hinton

1967

Susan Eloise Hinton was born in Oklahoma in 1948. Since young, she enjoyed reading. She found the typical “girls meet boys” stories don’t meet her satisfaction, and at age 16 she started writing her own novel, The Outsiders. The book was inspired by young people in her high school, telling the story of two gangs and their rivalry set in Oklahoma. The Outsiders was published in 1967. Since then it has sold more than 14 million copies in the US. S.E.Hinton also writes children’s books and adult fiction.

Read her work here.

Sonya Hartnett

1984

Sonya Hartnett is an Australian author. Born in 1968, she has been called “the finest Australian writer of her generation”. At age 13, she wrote her first novel, Trouble All the Way. It was published in 1984. Two years later, Sonya published her second novel, Sparkle and Nightflower. Sonya is a very prolific writer – for years, she writes almost one novel every year. Although her writings were mainly for the adult market when she was a girl author, Sonya later also published numerous picture books and young adult fiction.

Read her work here.

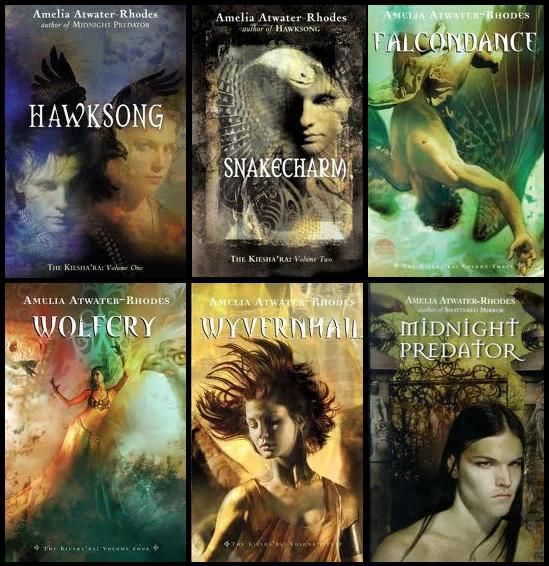

Amelia Atwater-Rhodes

1999

Born in 1984, American fantasy author Amelia Atwater-Rhodes began writing her first novel, In the Forests of the Night, at age 13. She published the novel at age 15 in 1999. The novel tells the story of a 300-year-old vampire named Risika and her life. In the Forests of the Night received much acclaim by both critics and teenage readers. Amelia went on to write three sequels of In the Forests of the Night: Demon in My View at age 16, Shattered Mirror at age 17, and Midnight Predator at age 18, which formed the “Den of Shadows Quartet”.

Read her work here.

Flavia Bujor

1990s

Flavia Bujor lived in Romania until she and her family moved to Paris, France when she was 2 years old in 1990. She showed a passion for stories from an early age. Flavia began writing her first novel, La Prophétie des Pierres (The Prophecy of The Gems, or The Prophecy of The Stones) at age 12. She would write when she got home from school, and email the chapters to her friends to read. The Prophecy of The Stones is a children’s story, featuring three girls named after precious stones who set out to unravel their birth mystery on their 14th birthday. The book was a huge success and was translated into 23 different languages.

Read her work here.

Helen Oyeyemi

2002

Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984. She and her family immigrated to the UK when she was four. Helen grew up under a lot of personal and family pressures, which led her to attempting to kill herself at age 15. She was rescued by her 11-year-old sister. At age 18, Helen began working on her debut novel, The Icarus Girl. The horror novel, about an eight-year-old girl born to an English father and a Nigerian mother, was published in 2005 and has since sold 20,799 copies in paperback in the UK. Helen dedicated the book to the sister who saved her life.

Read her work here.

Nancy Yi Fan

2007

Nancy Yi Fan was born in China 1993. At age 7, she and her family moved to New York. Since young, Nancy has loved birds. When she was 11, Nancy dreamed about two groups of birds at war, seeking freedom. She woke up and decided to write a novel about it. The novel, Swordbird, was published in 2007 and became a New York Times Bestseller. She then wrote two follow up books to Swordbird, Sword Quest (released in 2008) and Sword Mountain (released in 2012).

Read her work here.

Want to read Girl Authors?

Our Bookshop “Girl Authors” list gathers books from the girls featured in this show, as well as additional girl authors we identify every year. These books make great gifts for readers of all ages! Click the button below to view the list on Bookshop.org – and every time you purchase through this link, a percentage of your purchase is donated from Bookshop.org back to us, helping support continued research and programs like this exhibit.

Credits

Thanks to the archives and archivists who were interviewed for this exhibition. Special thanks to our exhibition team: Tiffany Isselhardt, Yuwen Zhang, Emily VanderBent, Jessica McCall, Emily Rawle, Asha Hall-Jones, Seav Love, Josie Evans, and McKenzi C.