The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II celebrated in 2012 serves a reminder of how, just over 60 years ago, a young girl became the ruler of the largest Empire the world has ever known.

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II celebrated in 2012 serves a reminder of how, just over 60 years ago, a young girl became the ruler of the largest Empire the world has ever known.

Over the past six decades, the world has changed enormously. However, just like today, life then was different for everyone and depended on whom your family was, where they came from, as well as where and when you lived. The British Empire attempted to homogenize the psychological experiences of those who were occupied. And regardless whether you lived at Home or Away, the Empire was ever-present and all-consuming.

This exhibition explores representations of girls of the British Empire, both at home and in the colonies, through historical photographs. Our mission is to discover through the similarities and differences, depending on geographic location, race, class, and decade, how girls participated and were viewed within the ‘family of the Empire’.

Using photographs and colonial postcards, we imagine a girls’ eye view of this world that lasted centuries and continues to have resounding impacts on the contemporary social and political landscape today.

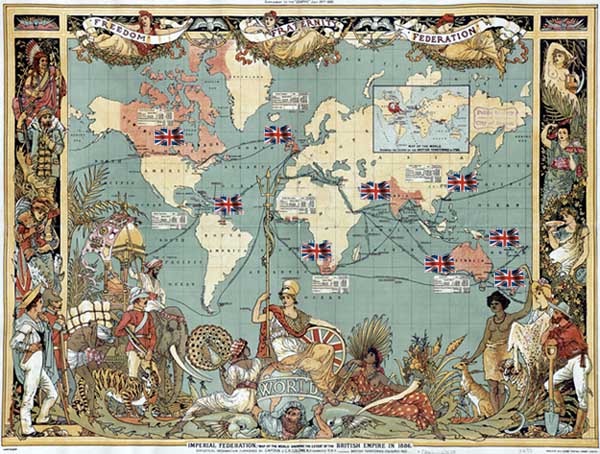

Empire

By 1922, the British Empire was the biggest Empire ever, controlling 25% of the world’s land and 20% of the population. It was made up of self-governing colonies with overarching responsibilities both to and from Britain.

It was this and the concept of the British world community that fostered the family metaphor. References to the imperial mother, daughter colonies and the manhood of nation are found in historical political and cultural discourses. Children were taught about their brothers and sisters around the world through systematic propaganda and institutional learning.

This global society had a shared language, literature and religion, but more importantly shared laws, ideals and institutions. However, this did not extend to all colonised people, who regardless of laws maintained much of their own cultures, which created tensions and led to violence and rebellions.

Colonial Photography

Studio portrait of two girls wearing mourning costumes, 1889-90, Kapakapa, Papua New Guinea. ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Oc, B52.3.

Photography was invented in 1826 and its development paralleled the growth of the British Empire. It has been said that a photograph metaphorically takes possession of the thing being photographed, thus giving power to the photographer over the object/person photographed. The relative ease of reproduction may have devalued the relationship between the viewer and the object and no doubt it created a desire, unsavoury yet legitimate, to dominate.

Colonial photographers were almost exclusively men and they took pictures of the things they wanted—land, treasures and people. Postcards featuring printed images that could be written on and mailed developed as a phenomenon from the mid-19th century. They often showed picturesque scenes and were associated with the spirit of travel and adventure, as adventurers and eventually tourists often sent postcards home whilst visiting these exotic destinations.

However, the colonial postcard holds specific significance. These were often of naked natives—men, women, boys and girls—and exploitive poses, highlighting and appropriating all that was desirable about Empire. Thousands of such postcards crossed the world between far-flung colonies and outposts.

The colonial postcard was a celebration of colonialism, a form of propaganda available to everyone, regardless of where they lived or what position they held.

Queen Victoria

The figure of Queen Victoria is deeply entwined with ideas of Empire and colonialism. Ascending to the throne in 1819 at just 18 years old, Victoria reigned for 63 years, which is longer than any other British monarch to date. At the same time, she raised nine children. Victoria’s commitment to her role as a wife and mother personified the Empire through her portrayal as a benevolent matriarchal icon.

During her reign, the British Empire reached the height of its territorial acquisitions, yet Victoria herself never ventured beyond visiting continental Europe and Ireland. Her only experience of her far away subjects came when people were brought to visit her or even more bizarrely at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in South Kensington, where people, places and material culture of the colonies were literally on display.

Despite her status as a powerful ruler, she opposed the ideas of gender equality and women’s suffrage. It is hard to imagine a more ambiguous and contradictory message than the most powerful woman in the world essentially claiming she was inferior to all her male subjects, purely by virtue of her sex.

Girls' Perspective

Portrait of Hilda Gilandi, early 20th c, Solomon Islands. ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Oc,G.T.2575.

From the nursery, our functions in society and the world are set, regardless of culture. Girls become wives and mothers, not governors and administrators, so from a girls’ perspective, the British Empire was generally not an empowering force. Their experience was of little to no importance to the Empire itself thus was not officially recorded.

Typically a girl’s experience was mediated by her family, her society and had largely to do with where she lived and the rank of her father. Yet some girls had amazing adventures, vast educations and deep love for the places where they grew up, often attempting to mitigate the effects of the Empire as they participated in it.

The lives of all the people who became British subjects were changed forever, for the better in some respects, many for the worse. Looking back at some cultural practices, such as suttee/sati (widow burning) in parts of India, which was outlawed by the British, or the providing of girls’ training and education that was provided by the British, it can be tricky to make sweeping statements about good or bad effects for girls.

There is no questioning that the Empire had an irrevocable impact on individuals, families, communities, nations and the world. And typically girls bear the brunt of such wide reaching social and political change.

GREAT BRITAIN

Great Britain was the epicentre of the Empire. British settlers travelled to far-flung parts of the world in connection with colonial rule, often taking their families with them. Several generations grew up far away from their mother country. Yet they always called it ‘home’ no matter where on earth they were stationed. The Industrial Revolution changed society at home as well.

With the growth of factories and mechanization, people migrated in large numbers from the country into the cities and markets were flooded with materials imported from colonies. There was more money available, yet the gap between those who labored for a wage and those who earned their money through other people’s labor grew hugely. Girls often helped contribute to the family’s income from a young age.

However, the 20th century saw a decline in Britain’s imperial prowess, accelerated by the economic and human cost of two World Wars. The nation struggled to adjust to its losses, and the difficult legacy of Empire is still felt in Britain today.

Gloucestershire

CARIBBEAN

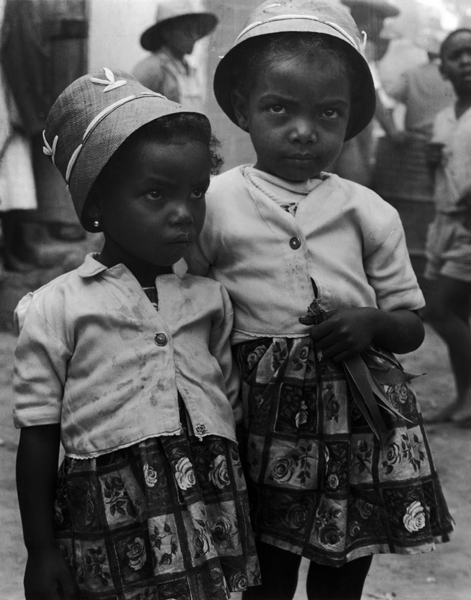

Most of the islands in the Caribbean were colonized at different times by the Dutch, French and British, but by the 19th century most were in the hands of the British. The Atlantic slave trade brought African slaves to many of the islands, where they worked on sugar plantations.

The British Caribbean islands achieved independence separately throughout the 20th century. While many non-European girls on these islands experienced great hardship, most of them gradually had better prospects and better access to education.

AFRICA

Africa is the largest expanse of diverse people that came under colonial rule from a number of foreign powers over centuries. Kenya officially became a British Crown Colony in 1920, and its previous incarnation was as British East Africa, a protectorate which developed out of British commercial interests in the area. The country was very popular with British settlers, and thousands of girls were born or started new lives in the colony. It gained independence in 1963.

Aden (in what is now Yemen) came under the jurisdiction of British India before 1937, and was a British Crown Colony from 1937-1963, when it became part of the new Federation of South Arabia as the Protectorate State of Aden. It did not achieve independence till 1967, though it was plagued by dissent against colonial rule for years beforehand, making it a dangerous place for British daughters to settle.

Northern Rhodesia was a British-governed territory in Southern Africa, formed in 1911. It eventually gained independence as Zambia in 1965, after first joining Nyasaland as the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland from 1951-63. Settlers and natives lived in relative harmony, largely due to the government’s unusual ‘indirect rule’ policy for the colony making it a more stable place for many British girls to grow up.

Kenya

Tanzania

Rhodesia/Zimbabwe

CANADA

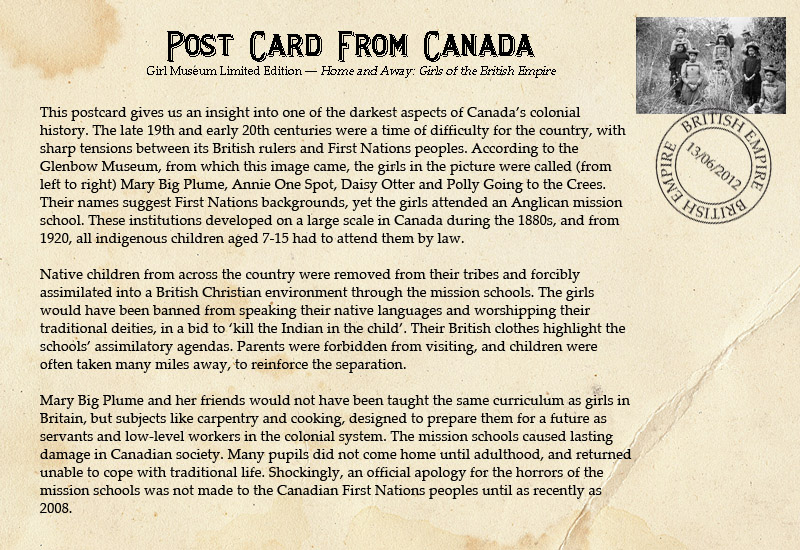

Canada has a long and fraught colonial history. After France ceded its Canadian territories to Britain after the Seven Years’ War, Canada was eventually united in 1840, but not confederated until 1867.

Large-scale immigration meant a huge influx of British girls in this vast nation, and First Nations peoples were forced out of their traditional homes to compensate. Such acts, combined with harsh policies of assimilation, created a legacy of hurt and anger that still resounds today.

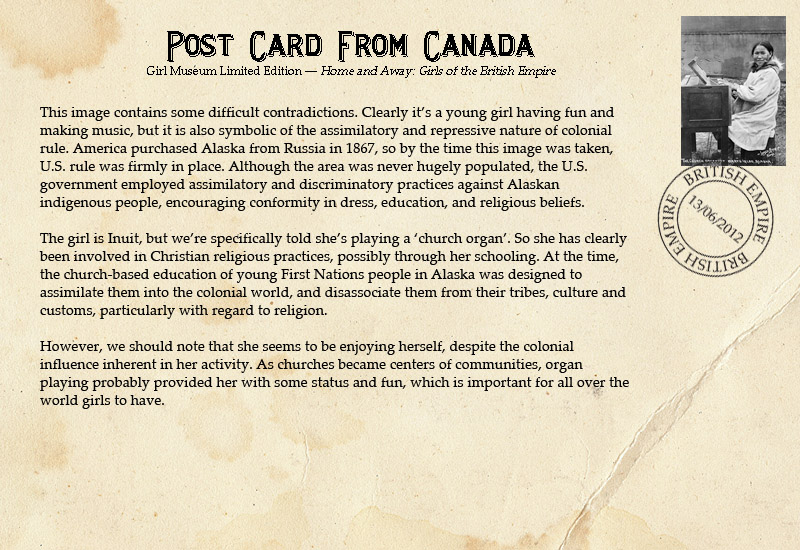

Unlike other territories discussed in this exhibition, Alaska was never a British colony. European exploration of Alaska began in the late 18th century, with Russia pursuing a colonising agenda, although full colonisation was never achieved. This image was included because it is representative of many colonial contradictions and similarities of the time.

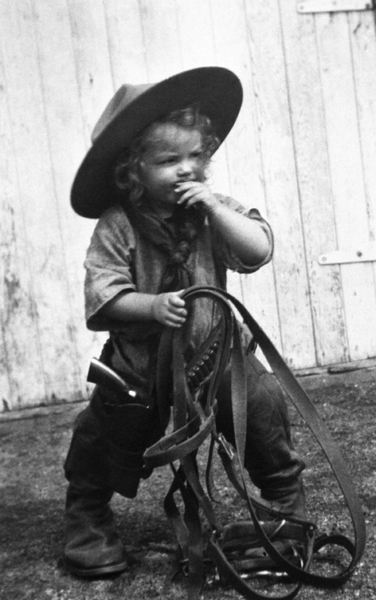

Alberta

AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND

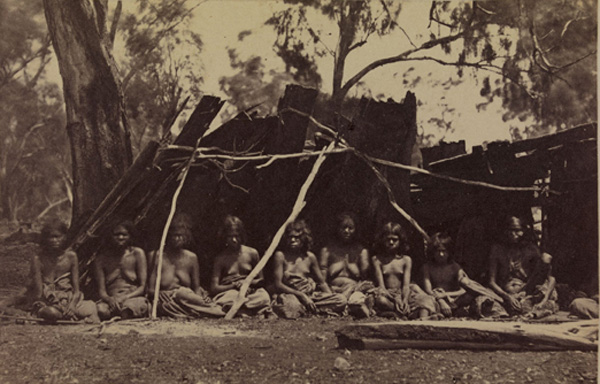

Australia was first colonised by Great Britain in 1788, and from then until 1792 most of the population consisted of convicts and those responsible for them. Indigenous Australians, who had been living on the land for tens of thousands of years, experienced great violence at the hands of the white settlers, and this persisted into the 20th century.

Australia became a nation in 1901, although it was still part of the greater British Commonwealth. The first white Australian girls were descended from convicts and free settlers, and were given a Western-style upbringing.

From 1788, New Zealand was considered part of the British colony of New South Wales in Australia. In 1840 it became a separate British colony, and representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty of Waitangi with the tribes of New Zealand, recognising Maori ownership of some of its land.

However, conflicts with Maori tribes occurred after the Treaty was signed British missionaries educated many Maori girls by at this time, and girls of the first white settlers also experienced a Western- style upbringing.

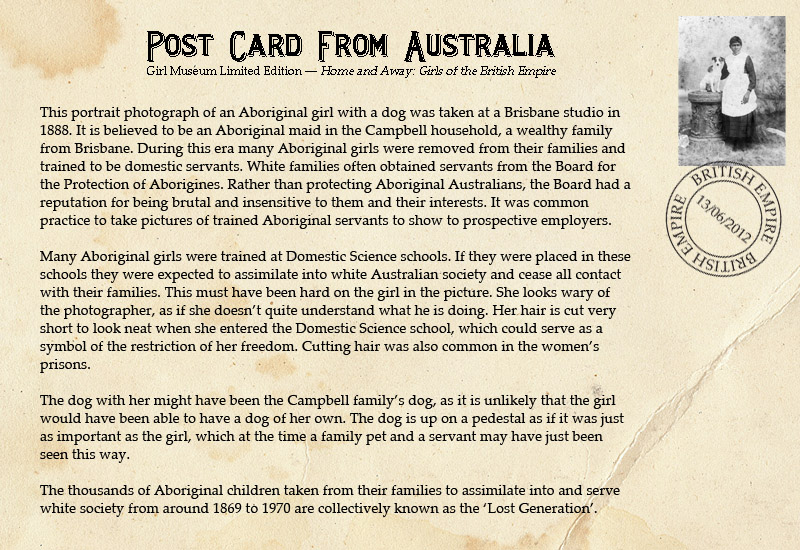

Brisbane, Australia

Auckland, New Zealand

Victoria, Australia

Christchurch, New Zealand

Victoria, Australia

EAST ASIA

Colonies in East Asia were the furthest away from Great Britain in the Empire. Traditionally a Chinese possession, Hong Kong came under British rule after the First Opium War, through the Treaty of Nanking in 1842.

British settlers brought their own education and social systems to the island, and although the territory was socially divided between the British and the Chinese, relations were fairly stable. Therefore, Hong Kong became a popular and exotic outpost of the Empire, attracting the migration of many British families.

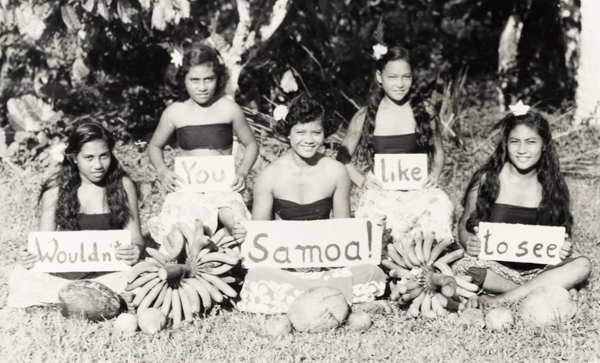

SOUTH PACIFIC

Islands in the South Pacific were left relatively untouched by Western nations until the 19th century. Yet by the beginning of the 20th century, Fiji and Papua New Guinea were under British control, Vanuatu was split between the French and the British, and Samoa was shared by Germany and the USA.

During this time, missionaries from Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand educated indigenous girls. The South Pacific islands achieved independence from their colonisers separately throughout the 20th century. Most currently provide at least primary education for girls.

British New Guinea/Papua New Guinea

Education Guide

For our accompanying discussion and activity guide, visit our click Educational Guide.

Images used in this exhibition were obtained with permission from the following museums, libraries and archives: Auckland Libraries/Special Collections, Archives New Zealand, British Library , British Museum , Glenbow Museum, Images of Empire (unfortunately recently closed), Pictures Australia, State Library of Victoria, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Note that the British Empire map on the home page dates from 1886 and was sourced from WikiCommons.

Credits

At Girl Museum, we bring together girls with great skills and intelligence to help produce our work. Each exhibition is a unique and exciting experience.

The wonderful team that worked on Home and Away: Girls of the British Empire was spread across the former dominion: Ashley E Remer from the USA, Briar Barry from New Zealand, Bronwnyn Lowe from Australia, and Chloe Grant and Sinny Cheung from the UK.

Special thanks to Dr. Michelle J. Smith for her encouragement and support—check out her website on Girls’ Literature—and to the School of Culture and Communications at the University of Melbourne for their financial assistance without which this exhibition would not have been possible.

Extra special gratitude to all the girls who did their best because of and in spite of the British Empire.