If someone took a picture of you right now, what would it look like? What would you be wearing and doing? You might be holding a smartphone, playing with a pet, doing homework, or listening to music. Your portrait would say a lot about you as an individual, but it would also show what it was like to be a girl in 2019. Your picture could become a document telling future historians how girls lived, dressed, and spent their time when it was taken.

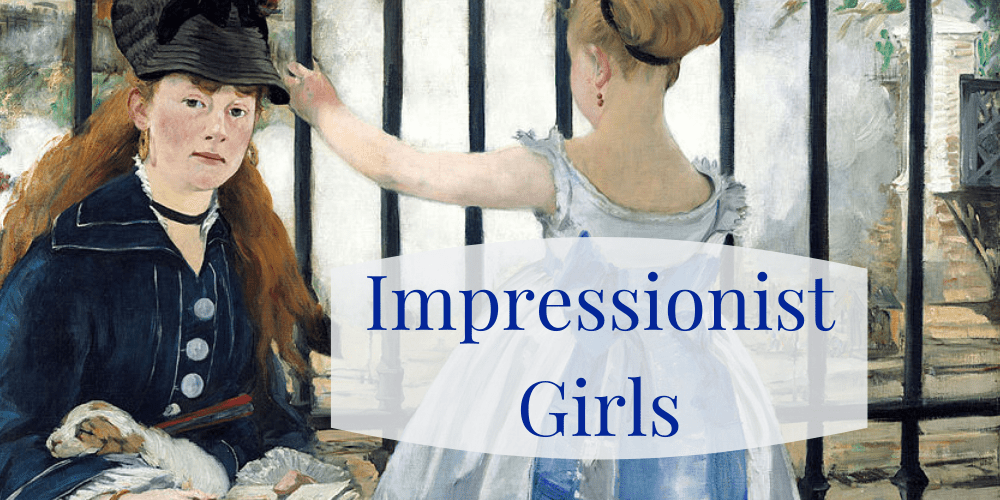

Impressionist Girls is a collection of portraits of girls painted in France between the 1870s and the early 1900s. They are pictured in a huge variety of situations: working, studying, pursuing their hobbies, and getting ready to go out. The artists who painted them wanted to capture the everyday lives of girls, who were often their own family members. Each painting tells us something important about the girl within it and her world. By looking at them and the clues given by the artists (as well as conducting research) we can grasp at what it felt like to be these girls: how they learned and worked, how they spent their spare time, and how they were affected by historical events around them.

Although many studies of these paintings focus on the artist’s choices of color and composition, responding to the works as pieces of art, we have chosen to reframe them, putting the focus back on the female subject. They are not just works of art but also stories about girlhood.

Impressionism

The Impressionists were a group of painters who lived and worked in France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, beginning in the 1860s and ending in the early 1900s. When their modern works were rejected by the Salon de Paris, an important art exhibition, the young painters Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frederic Bazille set up their own exhibition, calling it the Salon de Refusés. Although many viewers found their paintings shocking and tasteless, others loved the new style, which seemed fitting for an age of technological innovation, industrialization, and social change. The Impressionist group grew to include other artists, including Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, and Armand Guillaumin. Édouard Manet was their friend and colleague, and though he never exhibited work with the Impressionists, he is considered an Impressionist painter today.

These painters worked very differently from the painters who came before them. Instead of mythology or history, the Impressionists turned to the world around them for inspiration. They left their studios to paint scenes in railway stations, beaches, parks, cafés and theatres, and even backstage at the opera. In addition to hiring models, they often painted ballet dancers, laundresses, apple pickers, and waitresses at work, and their family members at home.

Their paintings also looked different. Impressionist paintings tend to have long, visible brushstrokes and bright colors that lie next to each other without blending or shading. Impressionists were particularly interested in capturing light and the ways it could change from moment to moment. Most of their paintings capture their subjects in motion or engaged in work or play, rather than posed formally: this shows the influence of photography, a brand-new invention at the time. Popular Japanese art prints also influenced their work.

Today, their revolutionary works are considered classic pieces of the art history canon.

Educating Girls

A girl’s education in the 19th century was quite different from the education that most girls receive today. Girls’ education also varied depending on their social background: if you came from a wealthy family, you might have the chance to pursue an education based in the arts and focused towards acquiring a husband in the future. In 1882, new education laws in France made education mandatory for all children under the age of 13, but before this time a girl from a working-class background might not have had the opportunity to go to school. Girls in this position would most likely help their family by working; as we can see in some of the paintings, they took care of animals or siblings or performed household chores.

In this group of paintings, the children that we see are girls from wealthy or middle-class families, as Impressionists tended to paint their own or their friends’ children. This means we rarely see what poorer girls were doing at similar ages, or even what girls lucky enough to be sent to school did while there. Even though these wealthier girls were fortunate enough to have an education, in general their circumstances still put them at a disadvantage compared to their male counterparts, who would have had access to more subjects and a fuller education. Women in France were not allowed to attend university or medical school until 1879. Relatively few girls achieved a career that could support them, apart from manual labor. Most depended on marriage to secure their future, which demonstrates the importance of education, but also the pervasiveness of patriarchal social restrictions.

Domestics

Armand Guillaumin, Mademoiselle Guillaumin, the Artist’s Daughter, Sewing. 1903. Private collection.

Armand Guillaumin, Mademoiselle Guillaumin, the Artist’s Daughter, Sewing. 1903. Private collection.

We can almost feel how tenderly the artist treats his subject: Guillaumin’s own daughter was the model for this painting. She is looking at her needlework intensely, which allows us to see her in an intimate moment. The girl is dressed in comfortable clothes on a couch with her hair down, so she could be working on her sewing before going to bed. The large bird embroidered in the blanket covering the couch may show us the achievements that she could aim for one day if she keeps up her embroidery. It also shows the influence of Japanese and Chinese design, which were immensely popular in France during this period.

Lessons

Alfred Sisley, The Lesson. 1874, Private collection.

Alfred Sisley, The Lesson. 1874, Private collection.

Sisley’s painting shows his son Pierre and his daughter Jeanne sitting at a table with their heads bent over something in concentration. It’s not clear what Jeanne is doing, as her back is to us, but Pierre seems to be reading or writing. Would these two siblings have been given the same education? We know of some girls whose parents gave them the same education as their male siblings, but others had to learn what was expected of them, focusing on homemaking and the arts instead of literature and science. Jeanne went on to become a painter like her father and likely received an artistic upbringing.

Reading

Mary Cassatt, Auguste reading to her daughter, 1910. Private collection.

Mary Cassatt, Auguste reading to her daughter, 1910. Private collection.

Cassatt lets us see an intimate moment between mother and daughter. Even though the title says Auguste is reading, we seem to have caught her during a pause, as her lips are closed. The fact that she is reading confidently means she has been educated: mother and daughter’s fashionable clothes and hairstyles suggest this family can afford a good education for their daughter if they choose. As this girl grows, her mother will be responsible for teaching her other things like household management and etiquette, which will help her to make a good marriage.

Even though we do not know the content of the book, it seems to be boring the girl, who stares off into the distance. She will come of age in a very different world than her mother, reaching young womanhood in the tumultuous period of the First World War or the 1920s.

Music

Berthe Morisot, Lucie Léon at the piano, 1892, Private collection.

Berthe Morisot, Lucie Léon at the piano, 1892, Private collection.

Lucie Léon looks straight out towards the viewer; she is wearing a fine clear blue dress, which stands out from the darker blue of the wall. She also has a bracelet and her hair is long and well-groomed, tied with a bow at the top of her head. Lucie does not seem particularly happy to be practicing, but we know she later became a successful professional pianist. Like Berthe Morisot, she was one of only a few women in her field; although it was rare, some girls did turn their more limited education into a career. Julie Manet, the artist’s daughter and a close friend of Lucie, wrote in her diary that “Lucie would have preferred to play croquet than pose for the painting.” The theme of girls at the piano is a common one in this period; well-off families took pride in owning pianos and paying for lessons for their children, and well-brought-up girls were expected to have some musical training.

This recording (date unknown) features Lucie Léon and her husband playing Chabrier’s Valse Romantique No. 1 for two pianos:

Sport

Berthe Morisot, Girl with Shuttlecock (Jeanne Bonnet), 1888, Private collection.

A girl in a long loose pink dress holds a racket and shuttlecock, ready to play badminton (a net sport similar to tennis, only recently introduced to Europe at the time). Her dress would allow her to move freely to play and was also a way to show decency, as young women wore long skirts to conceal their legs and lower bodies (younger girls and very young boys wore short skirts). She is looking straight at the viewer and seems to have paused her game to pose for the painting. This is the type of game or sport that a girl of lower class would probably not play, as access to a badminton set would have been out of reach for them.

During the late 19th century, France experienced rapid industrialisation and transformation. As the City of Paris was rebuilt and modernised, its citizens witnessed the advent of machinery, increasing productivity, and a move towards a more urbanized society. With the rapid development of railroads, artists could travel further, inspiring idyllic scenes of leisure as experienced by the bourgeois (middle) class. Impressionists such as Camille Pissarro and Edgar Degas also looked to the realities of contemporary life and used the unconventional subject matter of women workers as a common theme to inspire them.

Though similar in their subject matter, the two artists’ approaches to representing these women were very different. While Degas was more of a realist and tried to express the real working lives of girls and women in a class-divided and capitalistic society, Pissarro looked to communicate his utopian beliefs by showing an idealised reality of the countryside.

Through exploring these two artists’ presentation of girls at work, we can see the contrasting points of view they took, but also see how these can be viewed together to create a whole picture of the theme. Whereas Degas presents real girls, highlighting the struggles and strains of their everyday lives, Pissarro focuses on the idealistic, giving the girls a relaxed and carefree persona. Degas looks to the future with the age of industrialisation whilst Pissarro is firmly rooted in past ideals, reflecting the huge challenges and changes all these girls would have faced as the world around them changed rapidly.

The similarities, however, lie in their focus on capturing the mood of a moment, and in their respect for the hard work these girls put in, whatever their profession and path in life. Though Degas looked to the city and Pissarro to the countryside, they both aimed to depict everyday scenes, capturing a “snapshot” of life as a French working girl during the late 19th century.

Camille Pissarro, Apple Picking, 1886, Ohara Museum of Art, Kurashiki.

Pissarro believed in achieving utopia through an anarchist society without class distinctions. He communicated his idealistic politics by depicting the agrarian lifestyle as peaceful, relaxed, and idyllic, with workers who coexist to cultivate the land away from the industrialization destroying it. Here, three young women are shown performing the manual labor common among workers in the agricultural lands of the French countryside. His workers appear harmonious and calm, allowed to enjoy and take pride in their work. The woman on the left takes a break to eat an apple, balancing her work with relaxation to complete his vision of an ideal future society. By portraying the work as containing little hardship, Pissarro shows us the pleasures of working in villages away from the modern, industrial city. These rural subjects set him apart from many of his contemporaries such as Degas, who preferred instead to focus on the urban and modern way of life.

Camille Pissarro, The Little Country Maid (La petite bonne de campagne), 1882, The National Gallery, London.

This is a room in Pissarro’s modest house in the French countryside. At first glance, with the depiction of a domestic servant, we may presume this to be a prosperous household. However, the model is likely to be Pissarro’s niece, Nini. This is in keeping with his anarchist views: Pissarro believed all people to be equal and we can see this through his dignified depiction of the girl maid, who were regarded as the lowest order of servants. Pissarro shows her as well kept and seemingly at peace with her work, in contrast to women workers depicted by other Impressionists, such as Degas. The fact that this girl is likely to be a family member further highlights the respect he has for the profession. He is unique in centering the domestic figure in his painting. He shows high regard for these girls, who worked long hours for low pay. The model’s hunched-over position conveys the arduous nature of the tasks. Pissarro communicates service as a dignified line of work and an integral part to any domestic life, no matter your wealth or class.

Edgar Degas, Women Ironing (Repasseuses), ca.1884-86, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Degas’ choice of subject lends us a snapshot of the Parisian working class: full-time ironers. Girls in this line of work were one of Degas’ favorite subjects, and he studied them and their work extensively throughout his career. Laundry girls were positioned at the bottom of the social ladder, and through this subject matter Degas could reflect the realities of working class girls living in Paris. Unlike his contemporaries, who often presented laundresses in a sexualized and one-dimensional way due to the public and manual nature of their jobs, Degas aimed to communicate the real, hard work involved. Here he has captured one woman pressing hard on the heavy irons and the other yawning, caressing her neck and holding a bottle of wine. The painting highlights their exhaustion from the physical labor and long, repetitive hours, and reveals the harsh conditions these women were faced with. By depicting these women as real, everyday girls, Degas gives this work a sense of dignity and attempts to dispel the sexual stereotypes and stigma around working class women and laundresses.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class (La Classe de danse), 1871-74, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class (La Classe de danse), 1871-74, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

In line with Degas’ aim to portray the realities of modern life, his ballet scenes often take place backstage, beyond the artifice of the traditional beauty and discipline seen on stage. In the 19th century, ballet was not a respectable profession, and was reduced to a demoralised spectacle for concert goers to look at the bare legs of young girls in opera intervals. This created a highly sexualised culture, with ballerinas often performing sex work for money and higher standing within the company. The Paris opera house even had an appointed room behind the stage to serve as a men’s club where male visitors to the opera could go to stare at and proposition the dancers. It was here that Degas focused many of his studies, expertly capturing the harsh reality of a dancer’s working life. In this painting, we see the dancers are visibly exhausted as they leave their class. Through the girls’ everyday gestures, he has been able to further emphasize the hard work and conditions of the rehearsal room, keeping with his realist views by portraying the harsh truth rather than an idealized version. Degas shows us that these girls are human.

Edgar Degas, The Mante Family, ca.1884, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Louis-Amédée Mante was a double bass player in the Paris opera. All three of his daughters went on to join the corps de ballet; two, Suzanne and Blanche, are portrayed here. One of the daughters is wearing street clothes, though Degas shows us she is a ballerina by her turned-out feet. We can guess the daughter on the right is ready for an exam, audition, or recital, as her facial expression hints at anxiety, her body seems closed off, and her foot is pointed, as if marking through her steps. Her mother also adjusts her hair behind her to perfect it.

The exams and training these girls would go through were brutal and the working conditions extremely harsh, but they were vital in gaining a position in the corps de ballet and for supporting their future. The importance of this day was probably immense. Mothers were notorious within the sector for essentially prostituting their daughters to lift them out of poverty, which is perhaps why she is so focused on ensuring her daughter is properly presented. Degas has shown the contrast of the hard work needed backstage to produce the beauty on stage. It is this realism that sets him apart from the other Impressionists.

Public Life

Etiquette was a crucial part of social life during the late 19th century. Impressionist and post-Impressionist artists captured this in their work in ways that can be hard to spot for a contemporary audience. These small yet meaningful clues act as a looking glass back into time, informing us about the world girls lived in and the way others saw them.

From ways to dress and behave, to public activities or places they were allowed to enter, a girl’s life was guided and shaped by what was considered proper etiquette. In France at this time, young women and men alike experienced fewer limitations in their personal lives as class distinctions were fading, but their gender still placed strict limits on acceptable behavior for girls.

Female artists themselves were deemed only capable of capturing appropriate and proper scenes in their work, ranging from still lifes to domestic scenes of women and children. As women were discouraged from travelling without chaperones, encouraged to spend time in the house, and rarely taken seriously as working artists, their artistic subjects look very different from their colleagues’.

All of these paintings portray how a young woman’s life was shaped in the latter half of the 19th century; whether by the expansion of the railway, the lessening of strictures on everyday life, or their inclusion in public places and matters usually handled or experienced by men. From education to exercise, the etiquette of public life reigned over these young women.

The Café

Édouard Manet, The Café-Concert, 1879. Oil on canvas, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland.

As women’s roles became more public in the 19th century, they were able to explore more of their cities. Impressionist painters captured many scenes of cafés filled with both men and women. This particular painting shows a crowded scene at one of the popular cabarets in Paris. Manet depicts the different ways in which a woman would have spent time at the café; from working as the entertainment, to enjoying a drink or two among male companions. The young woman at the bar unwinds with a drink, but seems to lack the easy confidence of the man beside her.

Although women were experiencing new freedoms in the public sphere, these were not universal to all women. Middle-class young women would not be seen outside of their homes without their father or husband or another appropriate chaperone. Unmarried women were expected to guard their reputations closely to avoid situations or even rumors that could damage their futures. Working women, although their days were far more difficult, enjoyed some more freedom of movement in the lively Paris nightlife.

Transportation: Rail

Édouard Manet, The Railway, 1873. Oil on canvas, The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

As railways continued to take over Europe, travel time between cities and regions decreased, allowing for people of all classes to experience the world around them in a new way. Young women were able to take advantage of the railway in order to visit family or friends, and many took the opportunity to move to the city, away from the more rural areas. The quality of life of many Europeans changed as well, with the ability to transport goods made quicker and easier.

While the child is entranced by the huge, noisy railway engines that dominate her environment, the young woman seems less sure about this innovation, which meant huge changes for city life in Paris as neighborhoods were razed to build stations and train tracks. The painting also shows the fashions popular for girls at the time: the young girl’s dress, with its tight bodice and oversized bow, is beautiful, but would probably not allow for much play or movement, unlike modern children’s clothing. The older girl’s dress is much more conservative, covering her from neck to wrist; it’s suitable for walking outside in the city.

Transportation: Carriage

Mary Cassatt, A Woman and a Girl Driving, 1881. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

In Cassatt’s painting, a young girl sits in a carriage driven by an older woman in a lush, forest-like park. The Bois de Boulogne is a large public park in Paris, France. In the mid-late 19th century, there were paths for walking and riding in carriages; and pavilions for entertainment for all classes, such as cafés and theatres, making the park a popular destination for Parisians.

There would have been plenty for young women to enjoy in the park: they could exercise, take in a show or a cup of coffee, or enjoy chaperoned walks with prospective husbands. The bicycle became hugely popular with young women, who wore special short skirts so they could ride without ruining their dresses. Cassatt shows us the new and more liberated woman of the period: not only is there a woman driving the carriage, but they are out in public for others to see, showing us how women enjoyed their new freedoms. Cassatt also excelled in showing us girls with rich inner lives and feelings of their own: the girl in the carriage seems to be lost in thought rather than smiling for the viewers.

Gloves

Mary Cassatt, The Long Gloves, 1889. Private collection.

The wearing of gloves was a matter of etiquette in 19th-century Europe. Women of different classes wore gloves for a number of reasons. For upper-class young women like the one in this portrait, there would have been different gloves for every occasion, ranging from funerary gloves to gloves for weddings or church. Gloves were to be put on before leaving the house and rarely came off until women returned home. Beside playing a social and fashionable role, they also protected young women’s hands from the elements.

As the 19th century progressed, so too did views on gloves. While wearing gloves was still seen as a matter of etiquette and elegance, there were more opportunities to not wear them and it was no longer necessary to always have them on as a matter of propriety. The long gloves in this picture are probably opera or evening gloves; this girl might be going to a party or concert, both popular ways to socialize and meet people while showing off your education and cultural values. This type of glove was so tight and difficult to get on and off that women kept them on even to eat in public; Cassatt has captured this girl in a private moment, before she goes out into the world.

Parks

Berthe Morisot, Chasing Butterflies, 1874. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Berthe Morisot, Chasing Butterflies, 1874. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Chasing butterflies is a favorite pastime of many children throughout history. Some things do not change! In the 19th century, butterfly collecting was deemed an educationally acceptable pastime for people, young and old, as there was much to be learned by collecting insects of all sorts. Scientific advances and expeditions to collect specimens from outside Europe, and the opening of natural history museums, zoos, and botanical gardens throughout the century led to widespread public interest in science.

One of the leading lepidopterists (scientists who study moths and butterflies) during the late 19th century through her death in 1940 was a British woman named Margaret Fountaine. While scientific lessons were deemed appropriate for young women, too much focus on STEM areas would be a cause for concern, as it took women away from their domestic roles and priorities. Chasing after butterflies was considered good exercise for young women like the ones in Morisot’s painting, as it encouraged them to spend some time outdoors on their own families’ properties or public parks.

In the 19th century, women’s clothing of extravagant and restrictive garments were a sign of social status and respectability. Fashionable undergarments, such as the corset, exemplified women’s limited role in society by constraining their physical mobility and rendering them unfit to work or perform household chores. It was considered immodest and immoral to wear loose clothing outside the home. Coinciding with this fashion was an alternative style of dress associated with items of men’s clothing, such as ties, hats, and waistcoats. This style of dress sought to challenge traditional gender stereotypes and women’s status in society.

During this era, informal yet highly stylish tea-gowns were worn in the intimacy of the home. In opposition to conventional Victorian dress these garments had a loose, comfortable fit and could be worn without a tightly-laced corset. In the 1900s, Japanese kimonos were worn as fashionable exotic at-home gowns and dressing gowns. The kimono was seen as a symbol of exoticism, practicality, and freedom within the domestic space of the home.

In the late 19th century, it gradually became more acceptable for upper- and middle-class women to participate in activities outside the home. Women simply wore their modest, everyday outdoor outfits for tennis and other leisure activities. Girls and women often wore a pinafore or apron over their day dress to protect their body and keep their clothes clean during work or play. In the 1800s the pinafore became a fashionable garment, decorated with gauzy lace, frills, and a dome-shaped skirt that curved around the sides so the dress underneath was visible. The style of the pinafore indicated the wearer’s social rank in society and their standard of living.

French rules of etiquette cited that a woman had to wear a hat or bonnet in public to protect their eyes and complexion from the sun. It was considered improper to go outside without a hat. In the 1880s, the straw hat or boater hat became a fashionable summer accessory for men and was also widely worn by women and children. The boater hat was made with split braid straw and finished with a plain silk band. It was light, breathable, and offered sun protection.

Girls’ private lives were profoundly shaped by their gender, just as their public lives were; the activities they pursued and the clothes they wore reflected society’s expectations of them as future wives and mothers or as decorative objects in a man’s world. However, the girls in these paintings are also living in a world that is changing rapidly around them. If we look at the clues in their portraits, we can see the tensions between tradition and a new world, where mass production and global trade created new fashions and patterns of consumption, and gender norms were being challenged by courageous and talented young women.

Paul Cézanne, Little Girl with a Doll, 1904. Private collection.

Paul Cézanne, Little Girl with a Doll, 1904. Private collection.

A young girl cradles her doll, looking seriously at the painter. She’s plainly dressed in a neat blue dress and pinafore and a straw hat; she might even be in school uniform. The hat tells us she’s outside, perhaps in a garden or a public park.

Dolls have been popular toys for girls throughout history. They are trusted friends and confidantes, and they allow children to role-play all kinds of social situations, preparing them to take on roles in their real life. Until the mid-19th century, most dolls were made to look like adults, but childlike dolls and baby dolls were hugely popular by the early 20th century, when this portrait was painted. Industrialization had also made manufactured dolls cheaper and more readily available. The shiny white head of this girl’s doll suggests it is a mass-produced porcelain doll.

She seems to be taking her play very seriously; with a pinafore protecting her clothing, she may be imagining herself as a mother, head of household, and hostess, practicing for the role she will play one day.

Armand Guillaumin, Portrait of Madeleine, 1901. Private collection.

In 1858, the Japanese government signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with America, which was followed by similar international trade agreements with England, France, Russia, and the Netherlands. This international exchange opened Japan to foreign trade, residents, and shipping. Japanese goods were imported and exhibited in the West, and became sought-after collectibles. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European and American fashion designers made garments from pieces of kimono fabric imported from Japan. Their work often incorporated motifs and techniques associated with Japanese design. Affordable, fully finished or unsewn components of a kimono could easily be bought from department stores, ready-to-wear boutiques, or through the postal system.

This painting depicts Madeleine Guillaumin, the 13-year-old daughter of artist Armand Guillaumin. Madeleine is robed in a beautifully patterned Japanese kimono reclining in a chair against an indistinct, patterned background. The robe she is wearing is simple in structure and silhouette. The garment drapes loosely across her body and masks her figure beneath it. This item of clothing is depicted in graceful lines and decorated with exotic, Eastern elegance. It is embroidered or hand printed in bright colours with a quintessential Japanese floral design with maple leaves. The image mirrors her good taste and knowledge of the latest fashion trends.

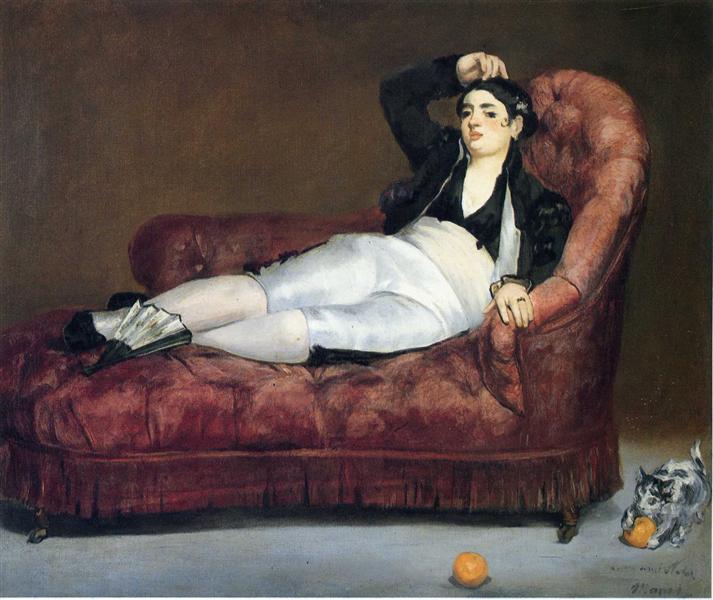

Édouard Manet, Young Woman Reclining in a Spanish Costume, 1862-63, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

Édouard Manet, Young Woman Reclining in a Spanish Costume, 1862-63, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

An unidentified model poses in an intimate scene reminiscent of a traditional reclining nude. This, along with Manet’s use of a formal studio setting backdrop, aligns him with the Old Masters he wished to be compared to. In fact, this painting was inspired by Clothed Maja by Francisco de Goya. Manet has replicated the women’s sexualized pose, yet has given the model a contemporary twist through the choice of clothing and use of late 19th century interest in fashionable Spain. The theatricality of the clothing also adds to the anonymity of the woman, showing us that she is playing a role and dressing up. The use of cross dressing, a popular but banned fashion in 19th century France, also positions her as a modern and rebellious woman. Manet additionally uses the male clothing to emphasise the female form, the pantaloons hugging her hips and legs, which female fashions of the time could not have achieved. The use of the clothing in this way hints at the conventional artist’s nude, the male gaze on the subject and the idealized body shapes and beauty standards of the period.

Édouard Manet, Eva Gonzalès, 1870, The National Gallery, London.

Édouard Manet, Eva Gonzalès, 1870, The National Gallery, London.

Eva Gonzalès was Manet’s only formal art student and the only woman artist he portrayed “at work.” In this portrait, he seems to struggle with portraying her as an artist and a model at the same time. Eva is dressed in an expensive and impractical evening dress, and she looks off to the side rather than towards the finished piece of art. This gives the feeling of a more conventional portrait, with the artist’s gear acting as props in setting the scene – not a depiction of an artist at work. The choice of outfit by Manet is key in his depiction of her as a modern woman and model to admire rather than as the artist that she was. The setting of the painting is also very telling: Eva is sitting on carpeted floor and not in an artist’s studio, further showing her role as a model portraying an amateur artist. Manet’s uneasiness with crediting Eva as a fellow artist reveals the portrait’s struggle in depicting her as the real artist and emphasises the difficulty women painters had in being respected for their art, unlike their male counterparts at the end of the 19th century.

Portraits of Julie Manet

Julie Manet, a French painter, model, diarist, and art collector, was the only child of Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot and Eugène Manet (brother of Impressionist painter Édouard Manet). She was born in Paris in 1878, four years after her parents were married. After her birth on the 14th of November, Julie became Morisot’s favourite subject to draw and paint. Her transition from babyhood to adolescence is depicted in numerous preparatory sketches, drawings, and paintings.

This collection of biographical images intimately explores the close mother-and-daughter relationship between Julie and Berthe. The first portrait of Julie shows her as a newborn in the arms of a wet nurse and later works such as Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laerte depict her as a willowy adolescent girl. As a child, she was also the subject of paintings by other Impressionist painters. Her uncle, Édouard Manet, illustrated four-year-old Julie perched on a watering can in a garden. Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted a portrait of a nine-year-old Julie in 1887, and in 1894 he produced a double portrait of Julie and her mother which may be the only painting Berthe appears in with her child.

Julie was educated at home with her parents. She received an artistic upbringing and later became Morisot’s art student and painting companion. She took lessons in drawing and painting with her cousins, Paule and Jeannie Gobillard. In 1892 her father died, and in 1895, when she was only sixteen years old, her mother contracted pneumonia and died. Following the death of her parents, Julie lived with her cousins who were orphaned by the death of their mother, Berthe’s sister Yves Morisot, in 1893. They lived in Julie’s family home at 40 rue de Villejust, Paris (renamed rue Paul Valéry) under the guardianship of poet Stéphane Mallarmé, and received financial support from Renoir.

In 1896, Julie helped organize a posthumous retrospective of her mother’s work along with Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and Renoir at the Durand-Ruel gallery in Paris. Julie kept a diary from the age of fourteen until she was twenty, when she became engaged. In 1900, Julie married Ernest Rouart; he was an artist and the nephew of the painter Henri Rouart. She gave birth to three sons, and died in July 1966, at the age of eighty seven.

This selection of paintings by Berthe Morisot, Édouard Manet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir capture an essence of Julie Manet’s childhood and adolescence. These images show the fleeting nature of childhood and the fragility and innocence of Julie’s life from the perspective of an observer.

By her uncle

Édouard Manet, Julie Manet sitting on a Watering Can, 1882. Private collection.

Like her mother, Julie Manet was a model in several works for her uncle Édouard Manet. Julie Manet sitting on a Watering Can, painted in 1882, demonstrates how Manet set aside his realistic formal compositions and embraced his contemporaries’ passion for painting figures and landscapes in the open air. The figure of his four-year-old niece is dressed in a blue summer dress and a rusty-red bonnet. She is perched on a watering can in an indeterminate garden setting, with her broad face set in a frown.

By her mother

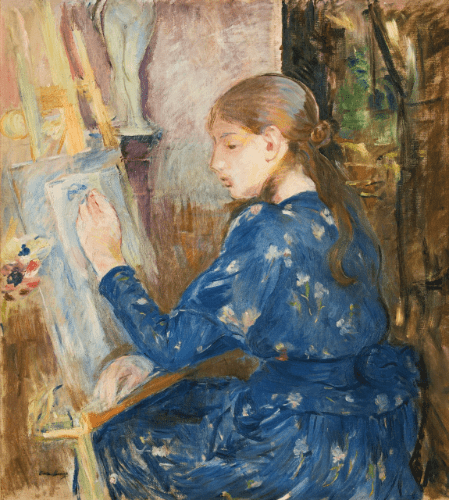

Berthe Morisot, Young Girl Writing, 1891. Private collection.

This painting depicts Julie Manet, at thirteen years old. Julie is seated in front of an ornate wooden easel placed in a tastefully decorated interior at her family’s home in rue de Villejust. She is dressed in a vibrant blue, floral patterned dress with a high collar and narrow sleeves. She is portrayed in the early stages of painting, with a single paintbrush poised over a mostly blank canvas. Her gaze is observant and calmly analytical of her chosen subject matter. She appears to be studying a classical statue from antiquity and its representation of the human form.

Another, by her mother

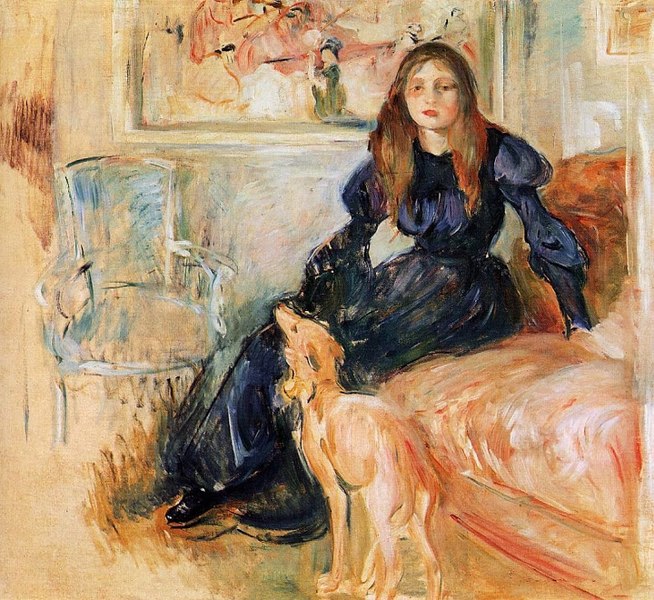

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laertes, 1893, Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris.

In 1893, Berthe Morisot painted a portrait of Julie at 15, with her pet greyhound. Julie is depicted in mourning attire: her father, Eugène Manet, had died in 1892. She is shown seated, wearing a black dress with a conservative neckline, a long narrow skirt, and puffed out sleeves at the upper arm that taper to a tight fit from the elbow to the wrist. Her sombre expression articulates her inner grief, yet she appears to draw comfort and reassurance from the presence of her beloved animal companion sitting nearby. The greyhound, named Laertes after a character in William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, was given to Julie as a gift by the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who was a close friend of the family.

By a friend of the family

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot and her daughter, Julie Manet, 1894. Private collection.

Morisot wasn’t the only Impressionist to capture Julie growing up; she frequently sat as a model for Pierre-Auguste Renoir. In April 1894, Renoir painted a family portrait of Julie, aged fifteen, and her mother. Julie is depicted sitting with her right hand in her lap and her left arm extended to the side across the back of an upholstered sofa. Berthe is regally presented in three-quarter length profile. They are both wearing simple A-line shaped dresses with leg of mutton sleeves which gather at the shoulders and fit tightly from the elbow to the wrist. Berthe’s hair is worn on top of her head, in tight curls. Julie is wearing an aureole hat worn towards the back of her head to frame her face in a “halo” effect.

Some of these girls, and others the Impressionists painted and sculpted, are now famous around the world, reproduced on calendars, postcards, and fridge magnets. Others have faded from memory. Some of them are known to us by their full names; we can write their biographies and read their diaries. In other cases, they are unknown to us except from their portraits: anonymous, mostly working-class girls who allowed a painter to sit in on their busy day. They were all real girls, whose full, complicated humanity was captured in a momentary pose, and then continued beyond the edges of the painting.

These girls lived through a period of great change, not only in art but in their way of life. Politics and technology moved quickly, bringing new opportunities like education, travel, and careers, but sexist attitudes continued to restrict most girls’ opportunities. Some young women challenged gender roles through dress or career, while others lived within them. All their lives are filtered through the eyes of artists, mostly male, with vastly different attitudes toward women. The Impressionist Girls dare us to look more closely at girls in art and read them in their complicated glory.

Curatorial Essay

Eva Gonzalès and gender in late 19th century France

by Jessica Eykel

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Eva Gonzalès, 1869–70, National Gallery, London.

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Eva Gonzalès, 1869–70, National Gallery, London.

The late nineteenth century saw a period of transition in France, where women were expected to negotiate their place in a new modern and capitalist society. A divide between the lives of men and women still existed, with women domesticated in the private sphere whilst men were free to roam and observe society in public life. Through the many Impressionist works depicting young girls and women, we are presented with women’s increasing freedom whilst simultaneously subtly exposed to the gender imbalances of nineteenth century France. Manet’s portrait of 21-year-old Eva Gonzalès (1870) is particularly significant in its portrayal of female identities.

Eva Gonzalès was unusual. In late nineteenth century France, female models for paintings were abundant, but women artists were rare beyond an amateur level. Women were restricted in the formal art education they could receive, and so many turned to established artists such as Manet for their training. Eva herself went to Manet for the dual purpose of posing and receiving criticism of her own work. His portrait of her reveals the tensions in their relationship, as she occupies a place between model and colleague.

Portraiture of women in the 19th century was traditionally used to reinforce social class and gender norms, presenting the vision of an ‘ideal woman’ rather than a true likeness. Manet’s style generally focused on beauty rather than realism. Manet’s portrait reveals his struggle in establishing which identity of Eva’s he wanted to represent. Was it to be a true likeness, or a portrait conforming to the male gaze of his audience?

As Manet’s only painting of a female artist at work, the portrait encapsulates the gender struggle and expectations that he faced, as it is clear he did not wish to present her as he would a male artist. This may have been because he anticipated an unpopular response from male spectators who expected a portrait to be flattering, and therefore idealised or prettified. The choice of an elegant and impractical dress portrays Eva as a beautiful woman that men could gaze at, rather than one who herself created beautiful and messy artwork. The skin on show is not appropriate for a portrait of a bourgeois lady and would have been more associated with the sexualisation of a model. This temptation to sexualise her conforms neatly to the traditional depictions of women throughout Western art history, an object to be admired rather than someone with her own identity and work. This is interesting to note against Edgar Degas’ work displayed in this exhibition, where his honest, almost ugly depictions of real women highlights the vast contrast between idealism and reality in art.

Depicting Eva painting a floral watercolour, rather than working in oils, further highlights this divide between male and female artists. Life drawing (sketching from live nude models) was a vital component of academic art studies, but was deemed inappropriate for women. They were therefore restricted from having access to this education. As a result, women had to turn their creativity towards less ‘important’ works of art such as the still life being painted here. This is particularly noteworthy in Manet’s case as Eva was not even well known for her floral still lifes – like Morisot and Cassatt, she mainly produced portraits. This hints at how Manet himself ‘saw’ her – an upper class amateur unable to contribute serious works. In addition, her eyes are not focused on her work and she is positioned on a carpeted floor, giving Eva the appearance of a hobbyist in her own home rather than a professional artist in a studio. These visual cues strip her of her identity as an actual woman artist and instead show her as just another generic sitter for a more highly-regarded male artist.

However, elements of the painting may suggest that Manet was aware of, and perhaps wanted to challenge, the gender divide in art. For example, by having Eva gaze beyond the frame instead of straight at the viewer, Manet may be hinting at his knowledge of the male gaze, giving her the ability to look rather than be looked at. Additionally, by positioning her within the private sphere (the Impressionists were known for painting outside and in public spaces), is he suggesting the limitations of women and their inability to walk freely as male artists would and could?

Overall, however, Manet has conformed heavily to the expected portrait requirements and gender roles of the Impressionist movement. The painting is unsuccessful in portraying Eva’s true identity as a working artist, and instead represents her as a beautiful model or amateur for the male spectator to gaze at. A male artist showcases his talent at the expense of a female one, reinforcing the inequality that separated them. In reality, Eva was not just a wide-eyed student dabbling in painting, but showed her work at the Paris Salon and at many other exhibitions, where it was positively received by art critics.

Manet’s treatment of Eva Gonzalès and her work has relevance for the way we see young women and their work today. In popular culture, women are still too often used as a decoration for a presumed male audience, as Laura Mulvey’s theory of the ‘male gaze’ in film suggests, instead of portrayed as developed characters with full personhood. In public life, young women find it hard for their ideas and expertise to be taken seriously and are shut out of discussions on the basis of their gender and age. 150 years after Eva’s portrait, we are still struggling to be seen for ourselves.

Suggested Reading

“History of Fashion 1840 – 1900”.Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Manet, Julie, Jane Roberts (Translator). Growing up with the Impressionists: The Diary of Julie Manet.

Meyers, Jeffrey. Impressionist Quartet: The Intimate genius of Manet and Morisot, Degas and Cassatt.

Roe, Sue. The Private lives of the Impressionists.

“The Corset: Fashioning the Body”. Google Arts & Culture.

Degas and the Dancers, Vanity Fair.

Credits

This exhibition was produced by Amber Barnes, Noelle Belanger, Jessica Eykel, Jennifer Lee, Alicia Garcia Pajares, Ashley E. Remer, Rachel Witte, and Jessical Yarnall. Many thanks to the team.