Warning

Some readers may find the content in this exhibition disturbing. We will be discussing themes such as religious persecution, devil worship, and physical and sexual violence. The time of witch hunts were terrifying and violent, and the acts that witches were accused of and subjected to are particularly disturbing. Reader discretion is advised.

Witch hunts occurred over centuries and are some of the most infamous historical events in Europe and North America. For hundreds of years, we’ve been captivated by the idea of females capable of magic. Perhaps surprisingly, girls figure prominently. They began as victims but morphed into accused witches.

Why? What happened to turn young girls – sometimes very young girls – into being witches?

Little Witches explores this question, looking specifically at witch hunts in history to find when girls were center stage in the persecution of witches…and why they still are today.

What Makes a Witch?

What is witchcraft? When did witch hunts begin? It is hard to know. While records of witch-hunting go back nearly 4,000 years to the Code of Hammurabi, beliefs before Ancient Babylon are less understood. Part of this is our sources: pre-Mesopotamian cultures did not keep written records (that we know of), so the knowledge and history was passed down through oral tradition. This makes it hard to pinpoint exactly when witch hunting – and therefore a belief in witches – began.

The Code of Hammurabi, written about 1750 BCE, codifies beliefs in witches through its laws. Specifically, it states, “If a man has put a spell upon another man and it is not justified, he upon whom the spell is laid shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of the house of him who laid the spell upon him.”

Notice a few things. First, the Code states that a witch is a man – there is no indication that women were witches. Second, the Code makes a distinction between whether a spell is justified – meaning that witchcraft was likely seen as both good and bad. Kind of like punishment. Did the person deserve a spell being cast on them? Why did one person cast a spell on another? Finally, it codifies a punishment that would be later repeated by Europeans: an accused witch would be put into the river and whether he drowned or not indicated his innocence. This left judgment entirely up to chance, absolving any living person from guilt. If the witch was guilty, he died. If he was innocent, he lived (though his accuser would be executed for making false testimony). In effect, the judicial system had no role other than to witness guilt and innocence.

Another problem is that, historically, witch hunts are a very Western (read: European and European-American) event. Witches have existed in many times and in many forms, but only in Europe and America do we find sustained historical witch hunting. While the practice later spread through colonization, it’s important to remember that not all cultures condemn witches.

For example, in Japan, witches are believed to have familiars (typically a fox) that grant them power through trickery or possession. In Korea, witches primarily rely on spells to influence others, while in Russia, a witch is more commonly called Baba Yaga or babka and seen as an older wise woman. It was only upon the invasion of Christianity in Africa and Asia that local beliefs – also known as folk beliefs – came to be associated with devil worship.

Little Witches focuses on European and European-American witch hunts, as these sources are readily available to our team at the time of writing. We also look at how European witch hunts spread through colonialism and into the modern world, profoundly changing folk beliefs into instruments of subjugation.

Francisco de Goya, “A radiant female figure beset by dark spirits; page 45 from the ‘Images of Spain’ album,” ca. 1812-20. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Intaglio depicting Hekate, Ancient Greek goddess of magic, made circa 50 BCE to 300 CE, provenance unconfirmed. Held by The British Museum.

Finding Girl Witches

Beyond cultural affiliation, witch hunts are a difficult topic to study – especially when it comes to locating girls within the stories. Notably, many witch hunts failed to record even basic biographical information about the accusers or accused. This reflected beliefs in women’s inferiority – believing that only their name and marital status mattered in the courts. Ages, places of residence, occupations, families, and personal religious beliefs often must be inferred from the records or found through extensive genealogical and historical research.

One of the biggest issues faced in studying girlhood is verifying the age of females that we study. Sometimes, a specific age is recorded. Other times, it is referred to by stating that a woman was “young” or “married” or “old” – and we have to try to determine what contemporaries meant by those terms, based on average ages of marriage and death. Finally, more often than not, there simply isn’t enough information available on the females in question. Male writers didn’t see the importance in writing down women’s lives – or even basic information. They were writing for themselves and for their time – not for those of us studying them hundreds of years later.

To find girl-aged witches, which we define as under 21 years of age, we have to take things with a grain of salt. There are records of early witch hunts where girl children were – or probably were – involved.

323 BCE

Theoris of Lemnos, who lived in Athens with her children, worked as a folk healer. In three surviving accounts, we know that someone accused Theoris of practicing magic and using her maidservant to traffic potions and incantations. Eventually, the maidservant informed authorities about Theoris’s practice. Theoris was put on trial, convicted, and executed – along with her children. We don’t know what crime was charged or why her children died with her. Magic was widely practiced in Ancient Greece, but the use of potions or drugs to kill was criminal – and it is possible that Theoris was making such drugs.

91 – 87 BCE

A five-year-long witch hunt in China reshuffled political power and led to Confucianism becoming the dominant way of life. In 91 BCE, Emperor Wu had been ill for a long time. Thinking it the work of witches, Jiang Chong convinced the Emperor to excavate imperial parks and palaces, searching for effigy dolls used to perform black magic and thus cause his disease. Anyone accused of using the dolls was arrested, and tens of thousands were put to death – including the Crown Prince and, ultimately, Chong himself. The hunt murdered entire ruling families, leaving a power vacuum later filled by Confucians. Because entire families were involved, it is highly likely that young girls were accused of being witches and executed.

1429 CE

In Korea, Crown Princess Hwi of the Andong Kim clan was accused of using witchcraft to gain her husband’s love. Princess Hwi cut her rivals’ shoes into pieces and burned them to ash, as well as drained the fluids from a snake and rubbed them on a cloth she wore. When her husband, the King, realied this, Hwi was confined, questioned, and then banished from the royal family and court life. Hwi’s maid – Ho-cho – was executed for teaching Hwi witchcraft. Princess Hwi was believed to be 19 years old at the time of her banishment.

The Rise of Modern Witches

Until the late 1400s, witches seemed to be a regional folk belief and community issue – not a widespread religious and social issue. What changed?

First, the Renaissance renewed interest in magic – especially the kind espoused in the writings of Arabic, Jewish, Romani, and Egyptian sources that were “rediscovered” by Europeans in the 1400s. Texts include descriptions of what we now call demonology or black magic, divination, and palm reading. Seen as exotic, many people were interested in learning about these arts or seeing them practiced, especially as answers to things that could not be explained by science, but the Catholic Church expressly forbade such magical arts.

What distinguished these new arts was twofold. First, it was learned magic, and second, it was exotic magic. During the Medieval period, magic was seen to come from the “fae” – magical or semi-magical beings that inhabited the world around them, naturally occurring and local to the region. Magic was more a gift or gifted ability that someone possessed, refined through practice and learning but ultimately dependent on someone’s innate abilities. During the Renaissance, magic became something that anyone could be taught.

In response to the popularity of magic, the Church fought back. Oddly, the fight included the Church engaging in the magical arts – specifically, demonology – in order to develop academic-based practices in finding and neutralizing witches. Interestingly, the Church remained rather lenient – punishments typically consisted of a day in the stocks, never death. The Church saw witchcraft as a superstition – a pre-Christian belief that needed to be corrected – or a mere illusion. Though witchcraft practitioners could be accused of heresy, it was in the context that they were not fully worshipping God as they should, not because they were casting spells.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, “The young Weisskunig (Maximilian I) instructed in the Black Arts.” Early proof for an illustration to ‘Der Weisskunig’. Woodcut. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

That changed from the 1430s to 1480s, when at least fifteen books about witches were published. One was Nicolas Jacuier’s Flagellum haereticorum fasinariorum (1458), which defined witchcraft as a form of heresy and argued that the “witch sect” was, in essence, a type of organized religious crime. This idea of an organized group of witches committing heresy was furthered in 1486 with Malleus Maleficarum, the most widely distributed manuscript to specifically make witchcraft a criminal, heretical act and offer guidelines for witch hunting. It was written by Heinrich Kramer – and this is important. Two years prior, Kramer had tried to prosecute witches in Tyrol (the alpine region of what is now Italy. It did not work – the locals hated Kramer and he was even expelled from the city as “senile and crazy”. Kramer possibly wrote the book in revenge, hoping his ideas would take root.

Notably, Kramer asserted that children of witches were also witches – because they had likely been initiated by their parents. But the Church actually rebuked the book – with the Inquisition and the Faculty of Cologne saying the book’s recommendations were unethical, illegal, and inconsistent with Church doctrine! Unfortunately for girls and women, the book became popular among secular (non-Church) courts. Following the Malleus Maleficarum, secular judges – and the people they presided over – became obsessed with finding and brutally prosecuting witches.

Another influence was the appearance of “witch families” in print culture during the late 1500s. Beginning with published confessions of accused witches, the “witch family” became stories of grandmothers, mothers, and daughters published in pamphlets and plays after 1590. Strong family ties became a defining feature of a witch family, with a family matriarch passing on their knowledge to the next generation and using magic to avenge wrongdoings against the family. As Deborah Willis explains, “Witch-parents behaved like proper parents, seeing to the protection and education of their young. They taught their children a kind of trade, passing on magical techniques and familiar spirits the way other parents passed on agricultural skills and livestock. Witch-children dutifully obeyed their parents and followed their instructions. Witchcraft therefore could spread through communities and across generations by means of behaviors that were viewed as godly in other contexts.”

The ideological stage for witch hunts was set. But what triggered such mass hysteria and accusations? As sociologist Nachman Ben-Yehuda wrote in 1980, many social changes contributed to the wider public believing what had already been written. As the Medieval world became the Modern one, many changes occurred in Europe: the growth of cities and industrial production led to larger populations, expansion of commerce, and the integration of new lands (like the Americas) into the European world. The environment was also changing. These changes were rapid and included:

- Lingering memory of the Black Death (1347-50) and similar plagues, which is estimated to have killed at least 50% of Europe’s population.

- Rise of Protestantism and contacts with previously unknown, non-Christian peoples.

- A distinct “middle class” particularly in new urban centers.

- Disease epidemics of plague and cholera.

- Little Ice Age (rapid cooling of North Atlantic regional temperatures from 1400 to 1850), resulting in much colder winters, freezing of major waterways, and failures of crops.

- Great Comet of 1528 (taken to be an omen of some kind).

Despite science’s attempts to explain all these changes, many people thought witches were to blame. It was easier to find a reason based in folk beliefs – and entirely absent of personal responsibility – than to wait for science to figure it out. Ben-Yehuda explains, “What could better explain the strain felt by the individual than the idea that he was part of a cataclysmic, cosmic struggle between the ‘sons of light’ and the ‘sons of darkness’? His personal acceptance of this particular explanation was further guaranteed by the fact that he could assist the ‘sons of light’ in helping to trap the ‘sons of darkness’…and thus play a real role in ending the cosmic struggle”.

By the mid-1500s, a witch hunt craze had consumed Europe. Initially focused on adults, particularly women, the latter half of the craze saw the appearance of child witches. So how did children – especially young girls – come to be called witches?

Execution of three witches on 4 November 1585 in Baden (Switzerland), illustration from the Wickiana (collection of Johann Jakob Wick, Zentralbibliothek Zürich).

Case Files

This section presents cases of girl witches from the mid-1500s to late 1600s. Two methods of exploration are presented: (1) A Google map shows the locations and details of each story, or (2) Images and full-text stories are presented in chronological order for those not comfortable with map-based explorations.

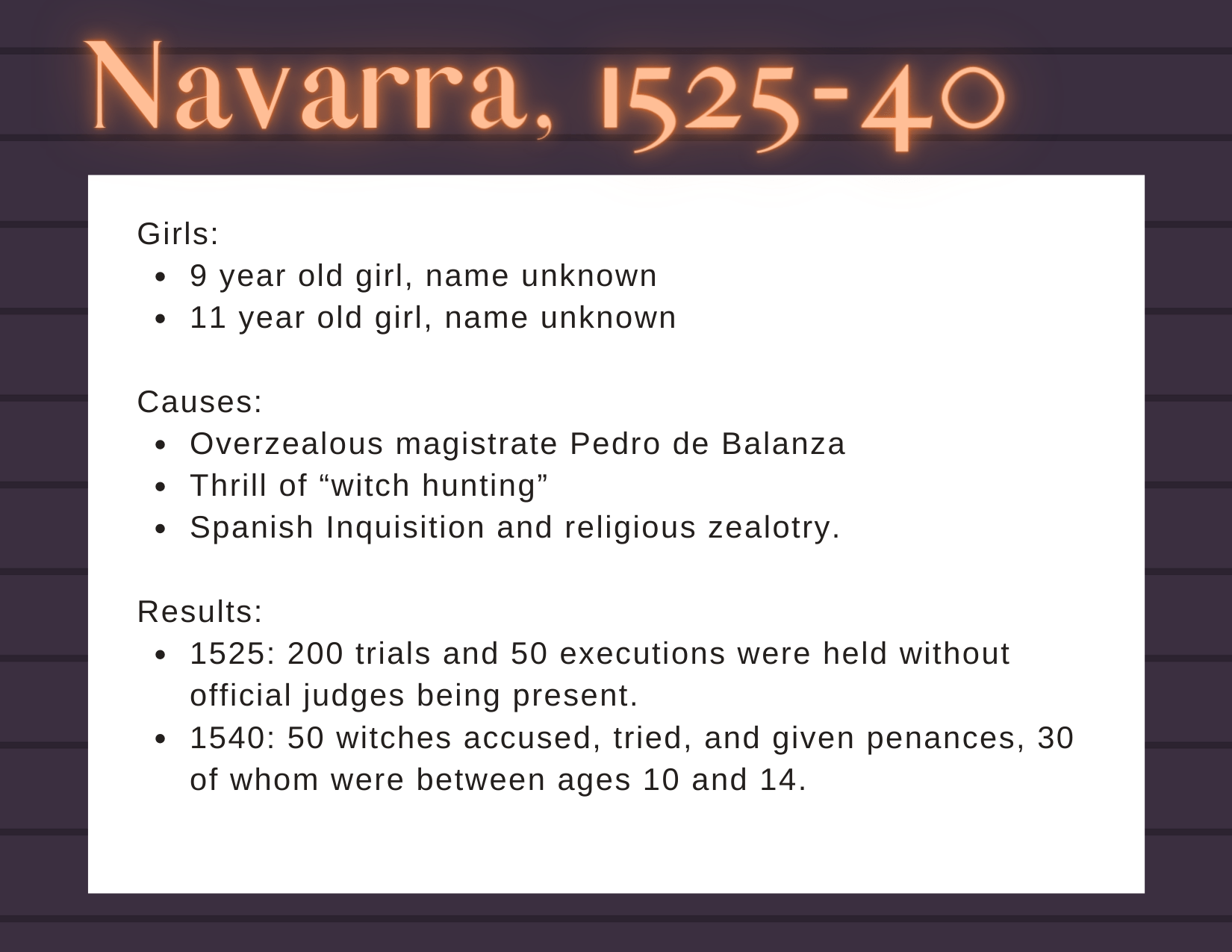

Navarra, 1525 and 1540

In 1525, two young girls – ages 9 and 11 – appeared before the Royal Tribunal of Navarra claiming to know about a witches’ coven. They agreed to testify in exchange for a pardon for having been part of the coven. Now called “witch-finders,” the girls accompanied magistrate Pedro de Balanza to Roncevalles and Salazar to hunt the witches. Touring villages, a spree ensued over 197 days, with up to 200 accusations and around 50 executions.

Officials throughout the region were appalled that executions were being held without trial in the region’s centers with other judges present (a tradition at the time). By August 1525, Balanza was forced to end the campaign.

Two girls started it all. We do not know their names, as most of the court records are now lost.

Only 15 years later, the region again saw witch trials. Brought before the Royal Tribunals, a group of people were accused of witchcraft. They were sent to the Inquisition, which that year recorded almost 50 confirmed witches – 30 of whom were between the ages of 10 and 14, convicted and given penances (not death).

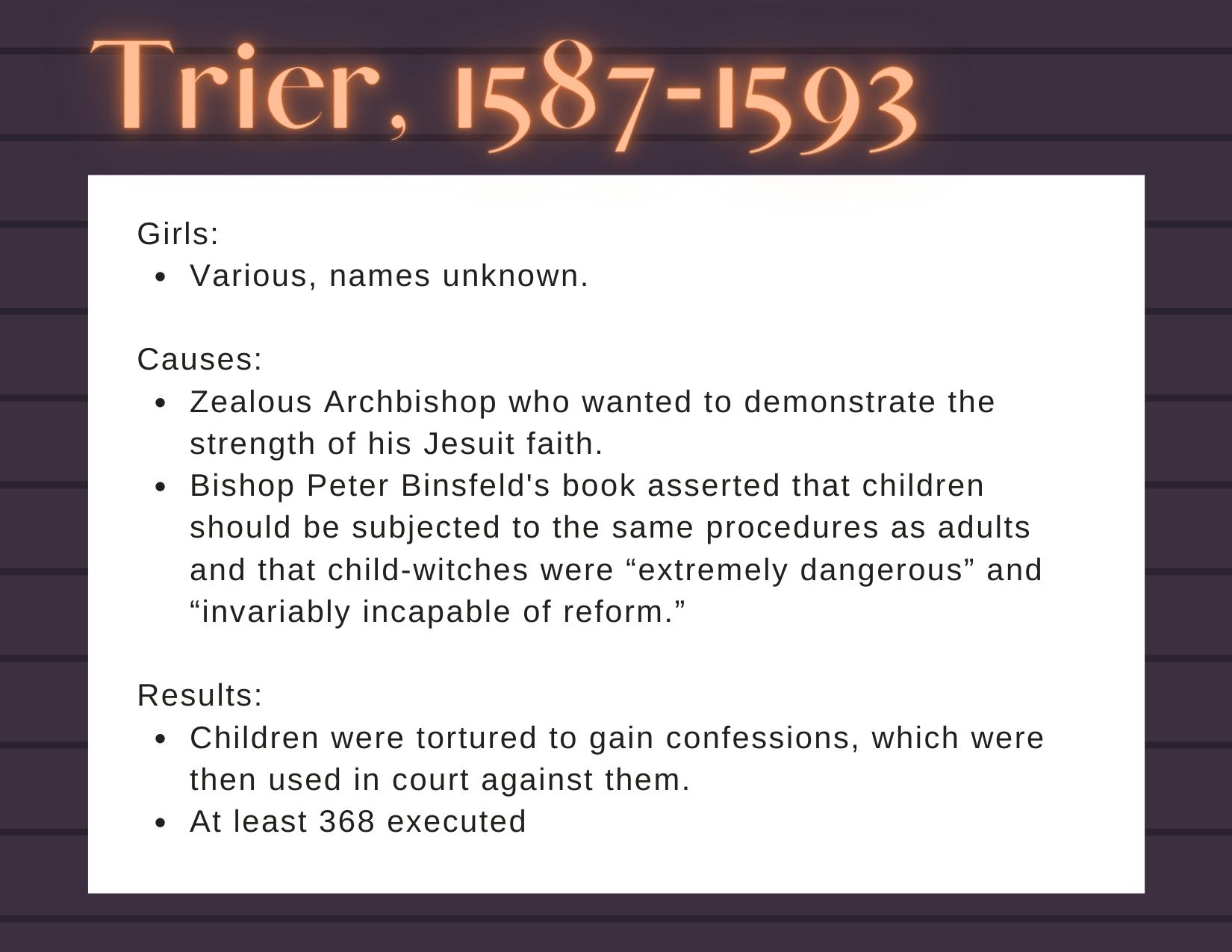

Trier, 1587 to 1593

It began in 1581 in Trier: Archbishop Johann von Schonenberg wanted to demonstrate the strength of his Jesuit convictions, so he decided to root out three great evils: Protestants, Jews, and witches. Blaming witches for the region’s sterility in recent years, Schonenberg was quickly backed by the people looking for someone to blame and others looking to confiscate witches’ property as their own.

Notably, Trier was the first confirmed case of child-witches. As explained by Dr. Robert S. Walinski-Kiehl, Senior Lecturer of History at the University of Portsmouth,

“In the course of the witch-hunt, children were discovered who claimed to be witches, and they denounced others whom they had supposedly seen at the witches’ secret, nocturnal meetings – the sabbats. This marked the start of children’s active involvement in the witch-hunts…”

The trials were guided by the recently published guidebook of Peter Binsfeld, a bishop who encouraged the witchhunt. Deviating from past advice, Binsfeld was the first to assert that children (then considered to be people under age 14) be subjected to the same procedures as adults. As a result, the children at Trier were tortured to gain confessions; their testimonies were used as evidence in court; and they were executed. Binsfeld considered child-witches as “extremely dangerous” and “invariably incapable of reform.”

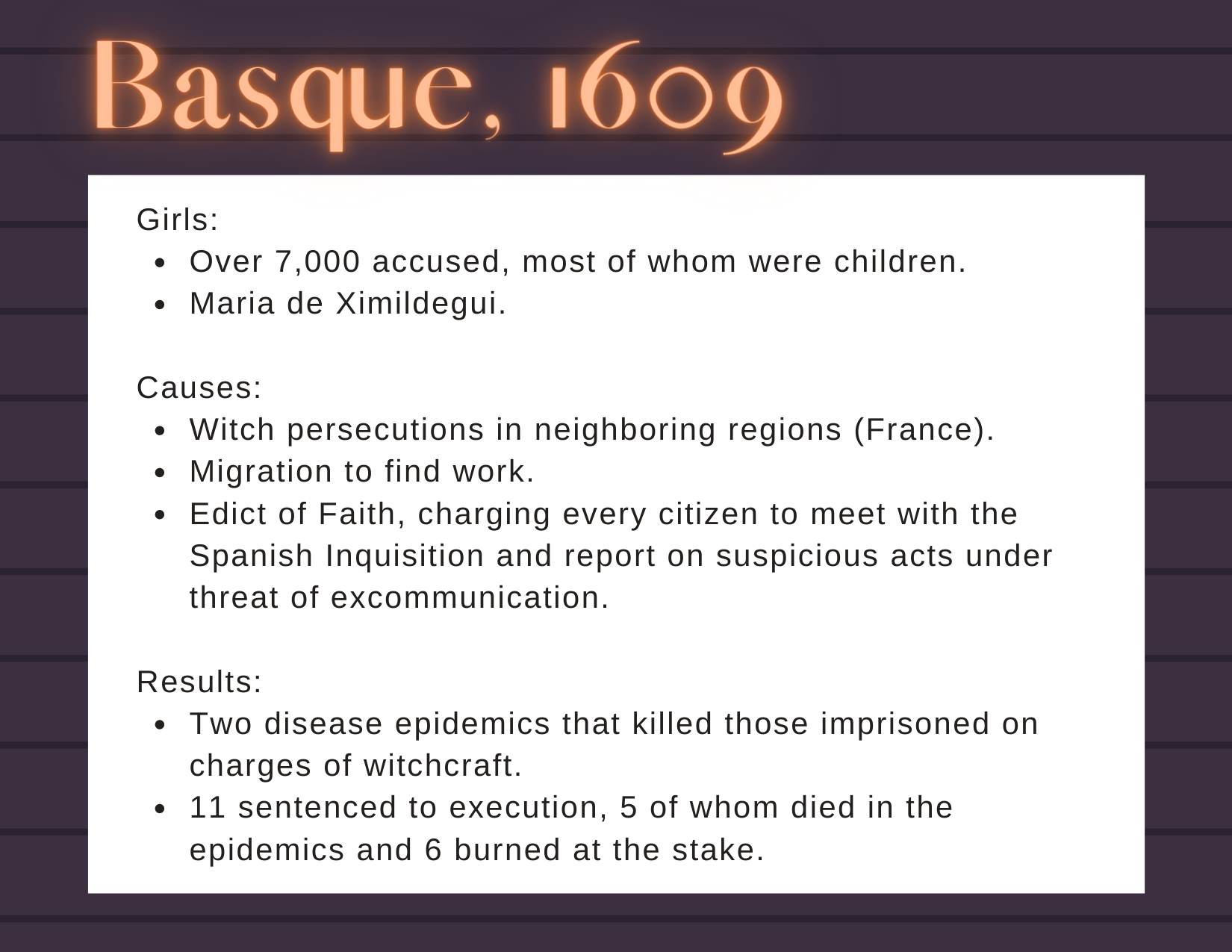

Basque, 1609

One of the largest witch hunts happened in Basque in 1609. Over 7,000 people – mostly children – were accused of witchcraft.

Emblematic of the Basque trials is Maria de Ximildegui, who had lived in France for three years. Fleeing witch persecutions there, Maria returned to Basque and told her family about the panics. Some reports say she confessed to being part of the coven, and then accused others of witchcraft. As a migrant, Maria was like many in the region – migrants or refugees who had experienced witch hunts in France. Those who confessed to being witches were forced to publicly confess and ask forgiveness. The community then pardoned them.

Though the community opted for confession and pardon, the Spanish Inquisition soon became involved. The number of confessions convinced the Inquisition that the town was controlled by a coven. The Inquisitors sent out the Edict of Faith, charging every citizen to meet with the inquisitors and report on suspicious actions under threat of excommunication. Suspected witches – including children – were imprisoned. The overcrowded conditions and poor nutrition caused two epidemics, killing thirteen.

Ultimately, in 1610, eleven witches were sentenced to execution. Five had died in the epidemics, and the remaining six were burned at the stake.

Despite over 7,000 accusations, the murder of only eleven seems odd. So why so few deaths, especially when more well-known cases like Salem, Massachusetts, had execution rates of 10% or more?

As historian Alexandra C. Steed explains, “The Spanish Inquisition had sole jurisdiction over cases of superstition, including witchcraft, and this meant that the Basque trials had a system of checks and balances in place that could prevent any one figure, secular or otherwise, from gaining too much power. The Inquisition maintained control and ensured that no one could create hysterical witch-hunts in the Basque region.”

In Basque, the Inquisition’s involvement saved girls’ lives.

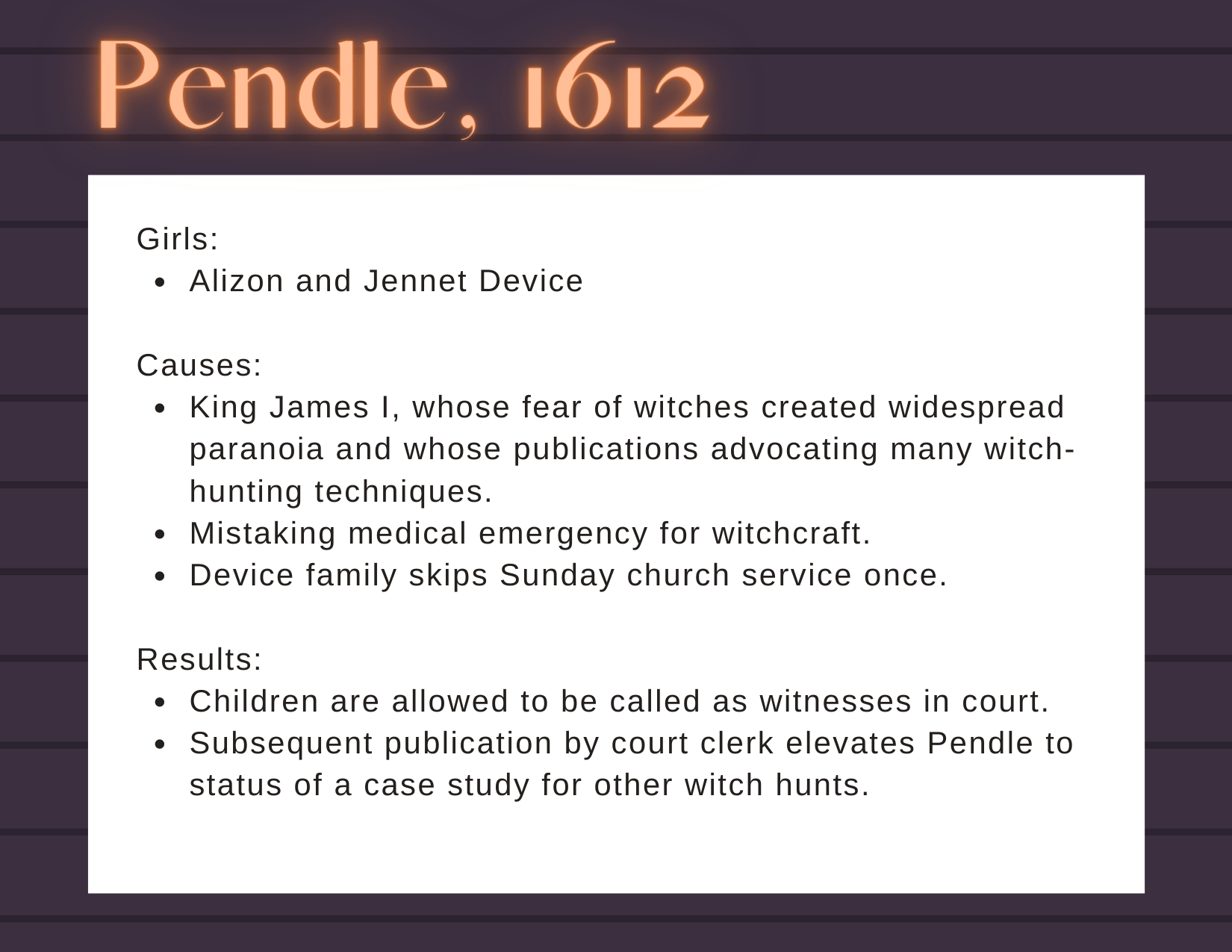

Pendle, 1612

Alizon and Jennet Device lived in Lancashire with their mother, brother, and grandmother. The family was poor – probably near destitute – but lived in a small home in the area. The grandmother, Elizabeth Southerns (nicknamed and often referred to as Old Demdike), was known as a “cunning woman” – a term used in southern England, the Midlands, and Wales to refer to what we would call folk healers. A cunning woman practiced folk medicine and magic, notably divination, typically within a Christian context. She acted as a healer when a doctor was unaffordable, a midwife, and a charm-maker and spell-caster whose works helped locate criminals or missing persons, identify stolen property, tell fortunes, or influence others. Her focus was typically on the practicalities of life – creating remedies to soothe the ailing or emotionally unwell. Old Demdike was likely appreciated by the poorer folk of Lancashire, who could not afford doctors to heal their sick or had any other means of improving their own livelihoods, so she was called upon to give them a sense of control, to help in times of crisis, and generally act as a cross between doctor, therapist, and fortune teller – as we would know them.

Old Demdike must have been decently liked – because her cunning skills were not what set off the 1612 witch hunt. Rather, the witch hunt was started in March 1612, when young Alizon (who, as we stated, was Old Demdike’s granddaughter) met a peddler on the road. Being poor, she begged the peddler for pins – and was refused. Perhaps like so many times before, Alizon cursed the peddler for not giving her anything, and began to walk away. Yet very quickly after, the peddler fell down on the road, convulsing into what we would now call a seizure. Passers-by went to the rescue, carrying the peddler into town. Alizon, distraught at her curse having worked and likely knowing the potential consequences, is said to have run to the peddler’s bedside and begged forgiveness.

Now, in most towns, Alizon’s curse would have been shrugged away as a girl’s fancies or even tantrum. But Lancashire was under the rule of a local magistrate who was ambitious and sought to gain favor in James’s land. When the peddler’s son demanded explanation and pointed out Alizon’s cursing, the magistrate was quick to investigate. During questioning, Alizon broke down completely. She confessed to having a familiar, which was her grandmother’s, and that her entire family were witches. Later on, Alizon realized she had implicated her family and tried to take some focus off of them by accusing the Whittle family, which included an elderly woman nicknamed Old Chattox.

However, this was only enough to start questions. The hard evidence was given on Good Friday, when Alizon and Jennet’s mother hosted a party instead of going to church. In the seventeenth century, this wasn’t just a sin – it was dangerous. Later hearing of the party, the local magistrate saw his opportunity. He arrested all who attended and claimed that the party was a witches’ coven meeting. Because who else would skip church? As word spread throughout the community, fingers were pointed in all directions. It was neighbor against neighbor as old feuds, small fights, and general suspicions blew into a full-blown witch hunt and expanded the circle of accused witches.

Through all this, Alizon’s little sister – 9-year-old Jennet – had been distinctly quiet. Yet, for reasons unknown, the magistrate called Jennet as the key witness at her own mother’s trial. This was a big moment in witch trial history – not just in Britain, but all over Europe and even reaching to America. Until this act, children could not be called as witnesses in English court. But with Jennet’s summons, children were now allowed to be called as witnesses in court – a precedent that has lasted to modern times.

The moment was documented by the Clerk of the Court, Thomas Potts, who later compiled his notes into a published book. In it, Potts states that when Jennet’s mother was brought to the stand, she screamed out at seeing Jennet enter the court. The mother was removed from court, and Jennet then climbed on a table and calmly denounced her mother as a witch. In the two-day trial, Jennet became the star – and her testimony sealed the fate of her family and neighbors, nearly all of whom were found guilty of causing death or harm by witchcraft. This was because in King James’s book on demonology, he had stated that the testimony of a child – even very young children – should be considered hard evidence of witchcraft. The next day, Jennet’s family – her mother, brother, sister Alizon, and grandmother Demdike – as well as the Chattox family and several neighbors were hanged at Gallows Hill. Jennet was now an orphan.

The Pendle case became famous, and Potts’ book elevated Jennet to a case study for witchcraft prosecutions across Britain and even the Americas. Ultimately, Jennet fell victim to her own schemes. At the age of twenty-nine, Jennet was accused of witchcraft along with 16 others by a 10-year-old boy. She was found guilty, but the case was referred to the Privy Council at the judges’ discretion. In those twenty years Jennet had become a woman and things in Britain had begun changing. Britain was now ruled by Charles I, who was more thorough about investigations. His reforms led to searches for more thorough evidence, especially when cases were appealed. For Jennet, this was crucial. Her case’s referral to the Privy Council led to a more thorough search. Looking for crucial evidence such as witch’s marks, the Council found none. So they turned to questioning the 10-year-old boy, who admitted his accusations were false and based on stories he had been told about the Pendle Witch Trial that had made Jennet a star. Despite evidence of her innocence, Jennet was kept in prison, since she was unable to pay her prison fees. Jennet disappeared from the historical record in 1636, just three years after her trial, most likely having died in prison.

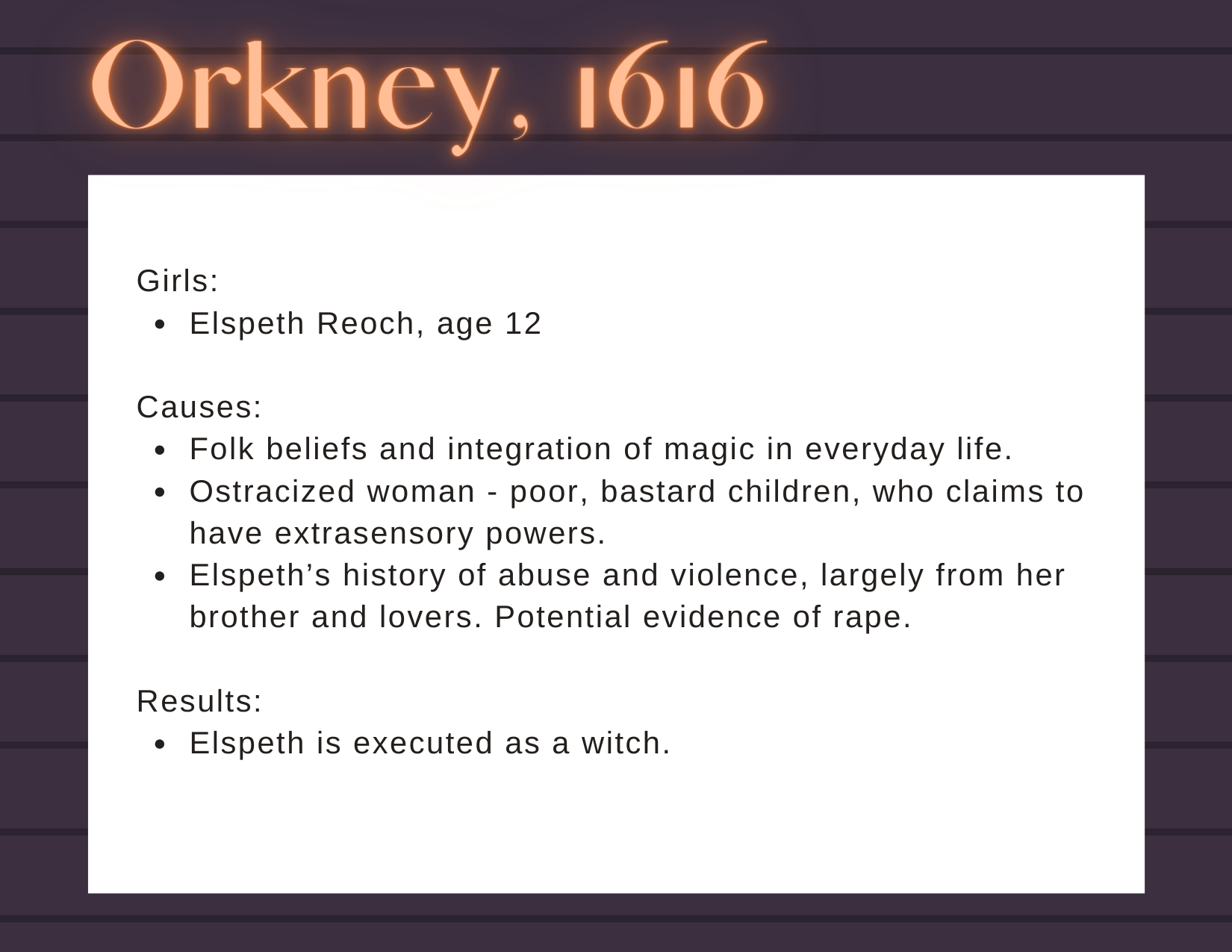

Orkney, 1616

On the island of Orkney in Scotland, 12-year-old Elspeth Reoch was surrounded by the supernatural. Folk beliefs held that witches and sorcerers were real, and magic was accepted as a part of life. Born to Donald Reoch, a piper in the Earl’s service, Elspeth began her witchcraft young but was not discovered until later in her life.

Elspeth’s life – even her age – is somewhat unknown. By the time she was tried for witchcraft, Elspeth was a young woman with two children (from different fathers). Described by historians as a wanderer or beggar, Elspeth utilized her claims of extrasensory perception to earn a living. This perception was likely derived from Elspeth’s violent life; symptoms that today we would recognize as trauma responses were largely seen as magical gifts.

In 1616, Elspeth was interrogated as a witch. In her confession, Elspeth stated that her magical abilities began when she was 12 years old. One day while visiting an aunt, she was approached by two men who told her how to obtain “second sight.” Two years later, while Elspeth was delivering a baby, one of the men appeared to Elspeth again, telling her that he was a fairy and her kinsman. He visited her for three nights, pressuring her to have sex while telling her that he was “neither dead nor alive but forever trapped between heaven and earth.” The man raped her, after which she lost her ability to speak. Elspeth’s brother violently beat her to cure the muteness, but nothing worked. (How Elspeth regained speech is not stated.) Her confession also stated that she used second sight to see the fates of people she knew and create magic spells, chanted while plucking the petals from a melefour herb, to cure illnesses.

Elspeth was charged with deceving the King’s subjects with the charade of muteness and committing the “abominable and diliesch cryme of witchcraft.” Her trial occurred on March 12, 1616, during which she admitted to rendezvous with the devil. She was found guilty and executed that afternoon by strangulation and burning.

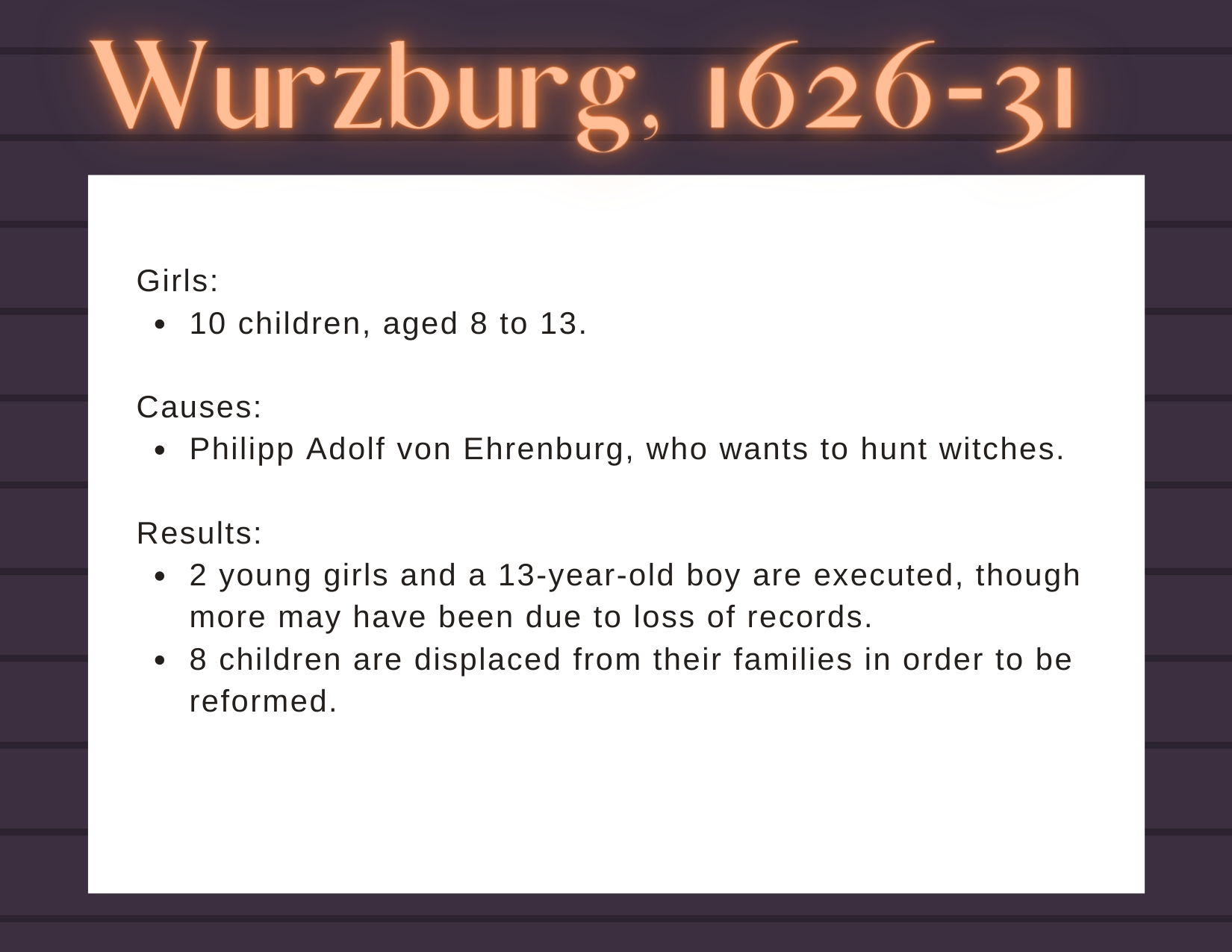

Wurzburg, 1626 to 1631

In the midst of many witch hunts, Wurzburg came to the forefront – in two years, at least 160 people were executed, 41 of whom were children.

It began with prince-bishop Philipp Adolf von Ehrenburg, whose search for sabbat accomplices extended to men and children (since he eventually ran out of old women to blame). In January 1628, ten children aged 8 to 13 were accused and examined for witchcraft. The children claimed their parents had made the witches. Two girls were executed, while the rest were sent elsewhere to be reformed.

More accusations and trials occurred in May, notably with extensive torture of children who would not confess. Thirteen-year-old Hans Philipp Schuh received 123 lashes before he confessed to learning witchcraft and having sex with a young girl. He was executed.

Unfortunately, the sources from Wurzburg are mostly lost, so we do not know their names or the details of girls accused during the hunt. The only reference comes from a letter in August 1629 that stated nearly 300 children had been proven witches, some as young as 7 years old when they were executed. The author stated plainly, “I can write no more about this misery.”

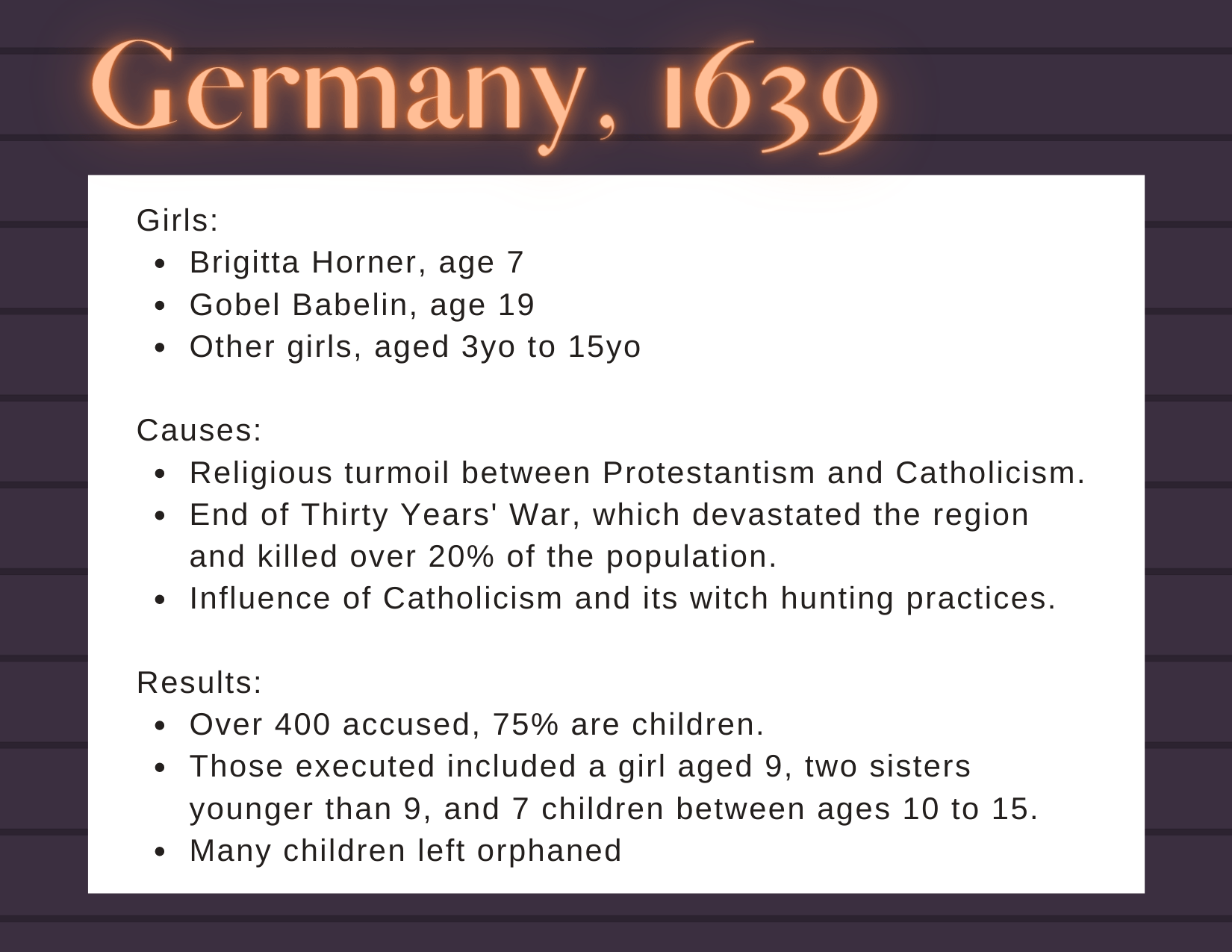

Germany, 1639

Germany’s witch trials were caused by similar factors to those in Lancashire. First, Prostestanism – a centuries-long mainstay of German culture – was challenged during the Thirty Years’ War. As the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II sought to enforce religious uniformity – meaning Catholicism – throughout his domains, Protestants in northern Germany formed the Protestant Union to defend their faith. Fairly quickly, northern Germany was challenged by southern – and Catholic – Germany. They lost in 1621, but the fight was continued by other Protestant countries who entered the war to defend their German brethren. Soon, the war became more about politics than religion – with Protestant Sweden (backed by Catholic France) more focused on keeping Germany from the political control of the Habsburg rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. (Basically, what started as a religious war quickly became about who controlled Germany and held the power there.)

The war was devastating to Germany. Nearly 20% of the population was killed during the war – that’s over 8 million people – and entire regions were devastated to the point of starvation and disease. In fact, the war ranks among the worst famines and plagues in history, perhaps the worst in modern European history. Though exact evidence is lacking, historians think population losses could have been as much as 50 to 60 percent in some regions, with nearly 2,000 castles, 18,000 villages, and 1,500 towns in Germany destroyed.

Adding to this, invading Catholics had more fervent beliefs in witchcraft, including adhering to texts such as the Malleus Maleficarum (published nearly 150 years prior). Inquisitions became common, producing mass hysteria that spread quickly throughout Germany. The war, crop failures, famines, and disease all caused the Germans to blame witches for their many problems (or perhaps to distract invading Catholic authorities from looking at anyone else). Those suspected of being witches were accused of humming songs with the Devil, murder, Satanism, or even simply being unable to state why they were crossing town. While some trials had been held in the decades prior, the late 1620s was the zenith of witch hunting in Germany, beginning in the Bishopric of Wurzberg.

Writing in August 1629, the Chancellor of the Prince-Bishop of Wurzburg stated, “Ah, the woe and the misery of it — there are still four hundred in the city, high and low, of every rank and sex, nay, even clerics, so strongly accused that they may be arrested at any hour. […] In a word, a third part of the city is surely involved. […] A week ago a maiden of nineteen was executed, of whom it is everywhere said that she was the fairest in the whole city, and was held by everybody a girl of singular modesty and purity. […] To conclude this wretched matter, there are children of three and four years, to the number of three hundred, who are said to have had intercourse with the devil. I have seen put to death children of seven, promising students of ten, twelve, fourteen, and fifteen.”

According to historical records, among the executed in Wurzburg were many girls, including the apothecary’s daughter; 19-year-old Gobel Babelin who was said to be the prettiest girl in town; the daughter of councilor Stolzenberg; a “little maiden nine years of age”; “a maiden still less than nine” and her sister; and a 15-year-old girl.

We can glean some information about these girls from cases of named girls, such as 7-year-old Brigitta Horner of nearby Rothenburg, whose circumstances might match some of the other girls. In 1639, claims were made that Brigitta was a witch – she attended sabbats by flying on a fire-iron and had promised herself to the Devil. Little Brigitta responded that she had no choice in becoming a witch – she had been baptized by the pastor of her birthplace, Spielbach, in the name of Satan – not God. Brigitta went on to identify members of her coven – most of whom were adults – which led to many arrests and Brigitta becoming nicknamed the “Little Witch Girl.”

Historian Alison Rowlands has worked on analyzing the case, suggesting the Brigitta’s actions were likely because she wanted attention – Brigitta was an orphan whose remaining relatives did not take responsibility for her and left her to wander the city’s streets; her stories gave her power, a name, and an identity in a world that had forgotten her.

Treated kindly, Brigitta’s stories were eventually deemed not plausible. She was released into the care of the local hospital for orphans and the elderly. Unlike so many others, Brigitta was ignored – and lived. She remained in the hospital for three months, and was then released to the care of her uncle. She was passed between relatives for some time, beaten, and eventually forced out of the city. She was discovered dead in a barn near the city in October 1640, at the age of 8.

From Brigitta’s story, we can glean that perhaps the witch-girls of Wurzburg were in similar circumstances. Some might have been destitute orphans, hoping that accusing witches would change their circumstances. Others might have been orphans singled out as witches because their extended kin did not want them – or because they slighted others, as little Alizon Device had.

Yet the accusers and murdered girls were not the only victims of witch trials during this time. Girls who lived through the trials were also victims, losing family members and security. One such girl was the daughter of Johannes Junius, the mayor of Bamberg who died during Bamberg’s witch trials in 1628. Johanne’s wife had been previously executed for witchcraft, and Johanne himself was accused and tried in 1628. He denied the accusations even after a full week of torture, but confessed on July 5, 1628, and was burned to death one month later. Before his death, Johanne wrote a letter to his daughter, Veronica, which was smuggled out of jail and delivered. In the letter, Johanne defended his innocence, stating, “Innocent I have come into prison, innocent have I been tortured, innocent must I die. For whoever comes into the witch prison must become a witch or be tortured until he invents something out of his head and – God pity him – bethinks him of something. […] I must say that I am a witch, though I am not. Must now renounce God, though I have never done it before. […] Now dear child, here you have all my confession, for which I must die. And they are sheer lies and made-up things, so help me God. For all this I was forced to say through fear of the torture which was threatened beyond what I had already endured. For they never leave off with the torture till one confesses something. […] Dear child, keep this letter secret so that people do not find it, else I shall be tortured…” He ended the letter stating, “Good night, for your father Johannes Julius will see you no more.” The letter is all we know of Veronica, the girl left orphaned by the Bamberg witch trials.

Ultimately, the German witch trials ended – at least in some parts – in 1631, when King Gustavas Adolphus of Sweden invaded. Winning the war trumped witchcraft.

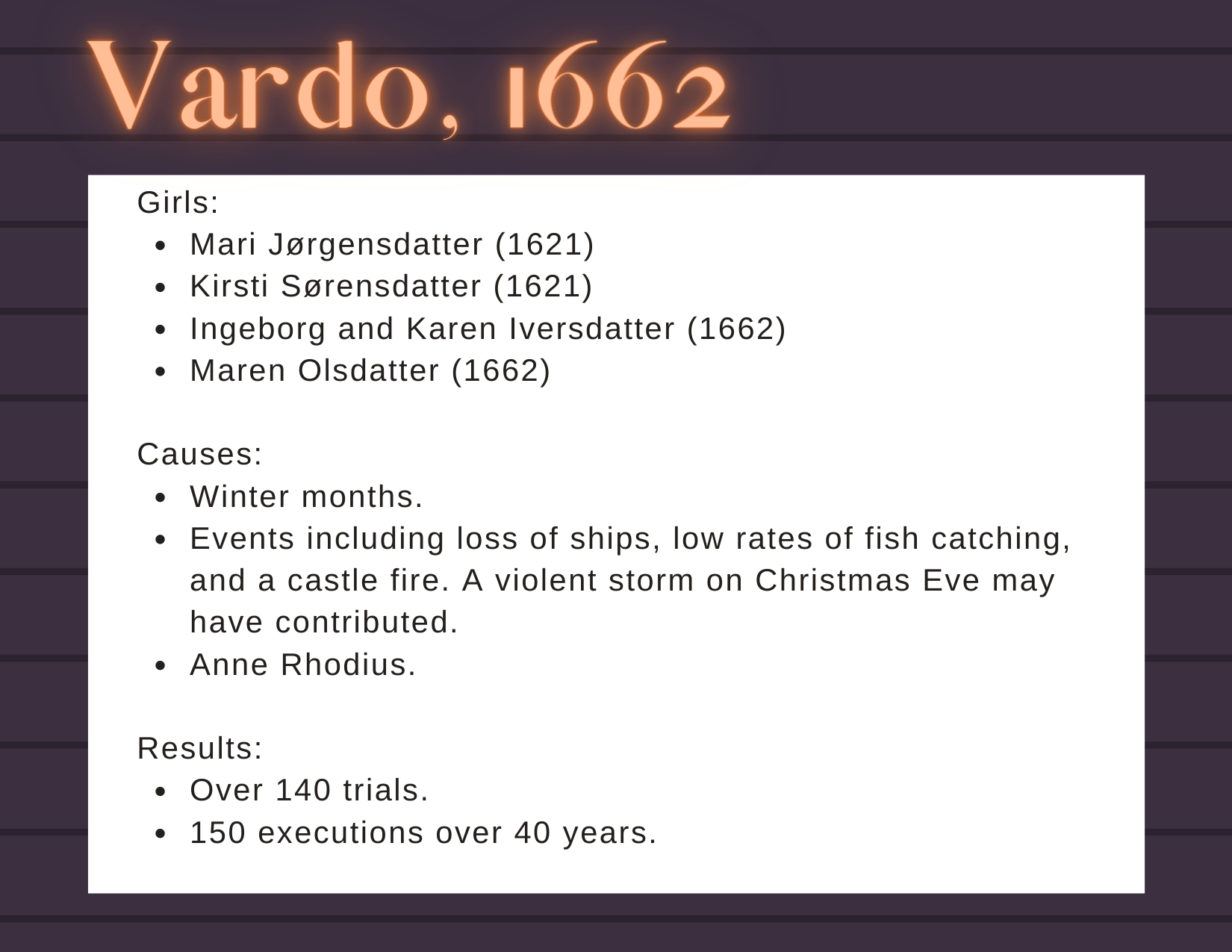

Vardo, 1662

“One Christmas Eve, while Mari Jørgensdatter was lying in bed, the Devil came visiting. Having awakened Mari, he insisted that she go to Kirsti. Mari did as the Devil requested. The Evil One asked Mari if she would serve him, while the two of them headed off on the road to Kirsti’s abode, saying that she would be richly rewarded. Mari consented to this. As a sign of their agreement, the Devil left his mark by biting between the two longest fingers of her left hand. The Evil One called himself Saclumb. Together he and Mari proceeded until they finally arrived at the one called Kirsti. Kirsti told Mari that she was to leave for Lyderhorn, in the vicinity of Bergen, but in order that Mari might arrive there as quickly as possible, Kirsti cast a spell on Mari, turning Mari into a raven.” – Rune Blix Hagen, Christmas Witchcraft in 17th-century Finnmark

This event was one of hundreds in Vardo, now known as “the Witch Capital of Norway.” In just 99 years, between 1593 and 1692, there were more than 140 witch trials in the village. Some were isolated, focused on a single individual, while others were panics–consisting of successive trials over a short period of time. These panics were where children were most likely to be accused, with the doctrine of demonology stating that anyone could be a witch. The three greatest panics were during 1620 to 21, 1652 to 53, and 1662 to 63. Notice how each panic spans two years? That’s because they were most common during the winter months.

During the panics, the accused were held at Vardohus Castle and executed at Steilneset. Nearly all of the witches were accused of “casting spells on ships, chasing the fish from land, casting a spell on the District Governor’s hand and foot, and trying to set fire to the castle.” These are interesting crimes, as each would have had dire effects on Vardo’s people. By bewitching ships or fish, witches influenced the town’s economy and caused suffering; by targeting the District Governor or castle, they attempted to remove town authority and safety. These were major concerns for the people of Vardo–and, unfortunately, were believed to be more influenced by the supernatural than any other factor.

Beyond these beliefs, there were historical events at work to spur the panic on. In 1617, Norway suffered a particularly violent storm on Christmas Eve. What should have been a happy time was marred by tragedy — of the 23 boats out to sea when the storm hit, a total of 10 boats and 40 men never returned. At the time, Vardo and neighboring Kiberg only had 150 residents each — so to lose 40 of the 300, all of whom were men or young boys, was a significant blow to the region. The villagers wanted a reason for the storm and the deaths. Two women, Mari Jøgensdatter and Kirsti Sørensdatter, were tried as witches responsible for the weather. Mari confessed, and other witches were tried. Mari was convicted and burned at the stake in January of 1621, marking the first death in the Vardo Witch Hunt of 1621. Within six months, 11 more women were convicted and burned.

Over the next 40 years, the trials continued and over 150 people were murdered for sorcery. Yet the first accusations of witchcraft aimed at young girls did not occur until 1662. That Christmas, two daughters of an executed witch – named Ingeborg and Karen Iversdatter – were brought in for questioning. Also brought in was Maren Olsdatter, their cousin. During the investigation, the children told so many stories that the local priest had a hard time making them say the catechism. According to a January 6, 1663 inquiry, Ingeborg celebrated Christmas Eve of 1662 in Kiberg. She had broken out of Vardohus Castle with Solvi Nilsdatter, an accused witch, by turning herself into a cat and carwling under the main gate. The Devil picked them up and brought them to Kiberg, where they partied with Maren Olsdatter and Sigri, the wife of Kiberg’s sexton. At dawn, the Devil returned her to the castle.

In another inquiry, both Ingeborg and Karen admitted to having learned witchcraft from their mother, who had been executed. Just twenty days later, on January 26, Maren took the stand and made her confession, claiming to have visited hell, where she had been given a tour by Satan. During the tour, she saw a “great water” down in a black valley, which began to boil when Satan blew fire through a horn of iron. In the water, people cried like cats. Maren would later give the names of five other women who had been witches, and confess that she, too, had learned witchcraft from her mother and her aunt, both of whom had been executed.

The girls were sent to Vardohus Castle to await a verdict, where they came into contact with Anne Rhodius — an outspoken women who’d disagreed with the governor.

What is interesting about these stories is how fantastical, and yet familiar, they are. Girls learning from their mothers – especially in an age where herbal medicine was common – is nothing new. Traditions had to be passed among the female line, and this could have included folk beliefs and medical remedies that others mistook for witchcraft. Additionally, the tall tales told by the girls were likely fueled by folk beliefs and common knowledge of demology. Maren later, at a court of appeal, stated that Anne Rhodius had misled her to lie against other people by denouncing them for witchcraft. The girls were highly susceptible to influence, and Anne Rhodius’s opinions and learned mind likely ingrained demonological beliefs in them. Additionally, all three girls had seen their mothers executed for witchcraft. Is it a stretch to think that the households they had left would constantly remind them of how witchcraft was believed to run in bloodlines? It is not a huge leap to think that these girls, traumatized by losing their mothers and ingrained with dark folk beliefs, were able to believe in witchcraft, Satan, and their own abilities.

Interestingly, on 25 June 1663, the last accused witches, Magdalene from Andersby, Ragnhild Endresdatter and Gertrude Siversdatter, along with her daughter Kirsten Sørensdatter, were brought from the witches-hole. They claimed that Maren and the other children had come up with their confessions under the influence of the exiled Anne Rhodius, who had also visited them in jail and threatened them with torture to make them confess. Magdalene, Gertrude, and Ragnhild were freed. All the children were acquitted in June 1663.

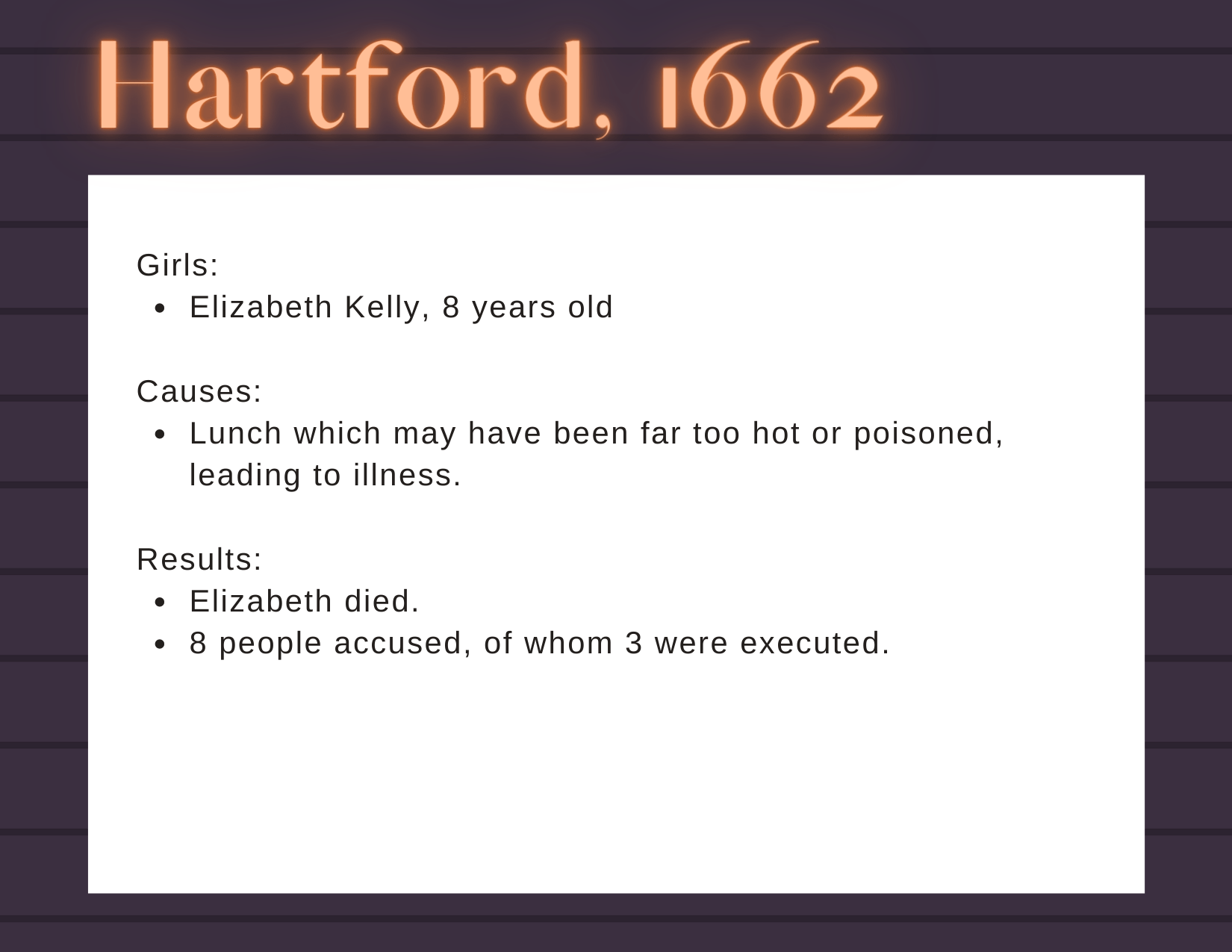

Hartford, 1662

In 1662, Ann Cole of Hartford began to experience what was deemed “diabolical possession.” She named other residents – Elizabeth Seager and Rebecca Greensmith – as witches responsible for tormenting her. Soon after, 8-year-old Elizabeth Kelly joined the accusers, claiming that Goodwife Ayres had made her sick. Elizabeth’s sickness was described by her parents: In late March 1661, Elizabeth ate lunch with her grandmother and Goodwife Ayres. The broth served was too hot, but Elizabeth did not listen and ate it; soon after, she complained of stomach pain. The next night, Elizabeth suddenly awoke and cried out that Goodwife Ayres was attacking her by choking, kneeling on her belly, breaking her bowels, and pinching her. Elizabeth’s parents calmed her, but again she cried out. Elizabeth’s suffering continued for two days, at which point Ayres visited her. Though the visit initially seemed to calm her, Elizabeth’s suffering returned that night and she died the next day. An autopsy on Elizabeth revealed that her body was still pliable (not stiff), her skin from the ribs to her belly was deep blue, she had a broken gallbladder, and there was blood in her throat.

By the end of the trials, eight people had been accused – three were executed, a fourth died of unknown causes, and four were freed.

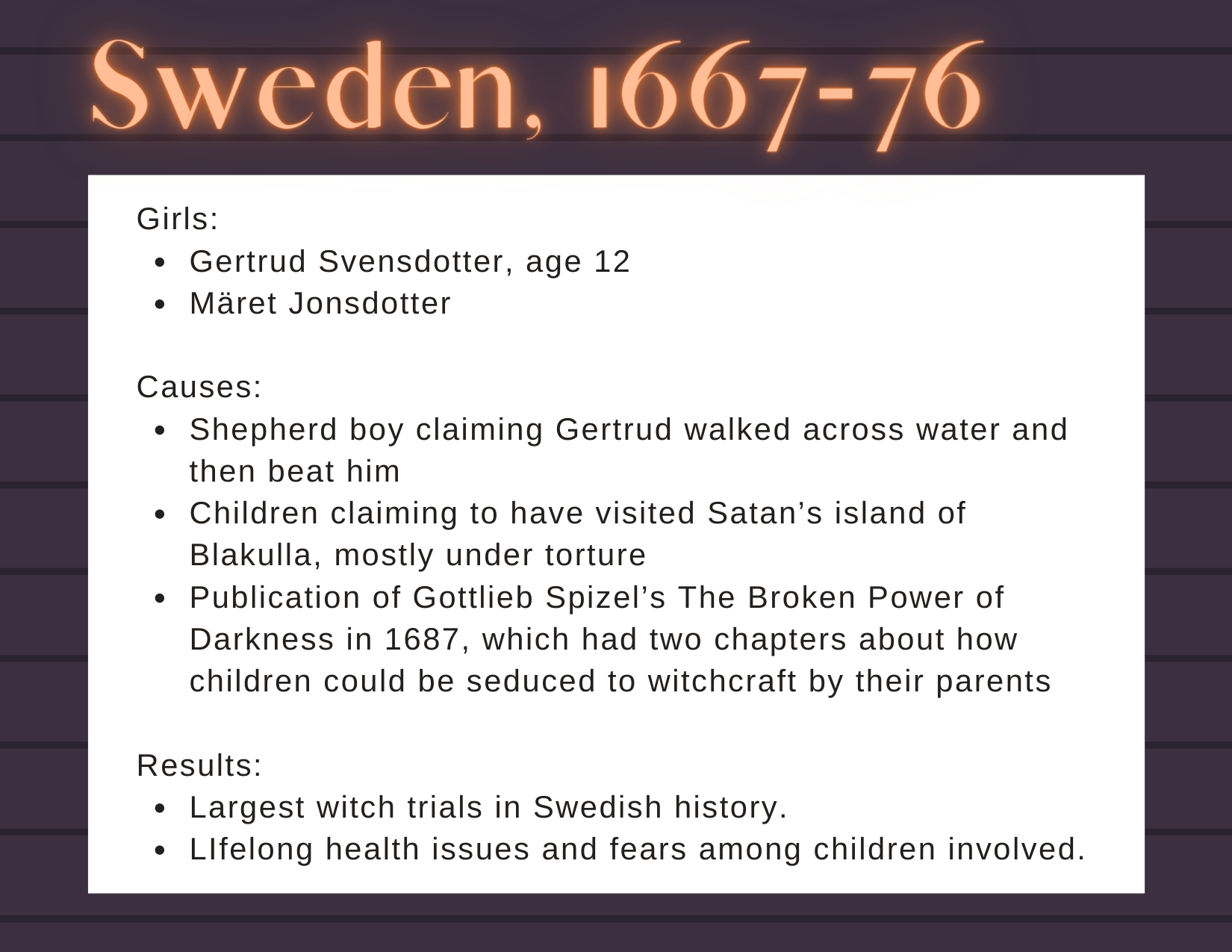

Sweden, 1667 to 1676

One autumn day in 1667, a shepherd boy in Sweden claimed to have seen 12-year-old Gertrud Svensdotter lead her goats across the river by walking on water. The two fought, and Gertrud had beaten the boy up. The boy told the village priest, who interrogated Gertrud. In her confession, Gertrud claimed to have become a witch four years prior when her maid – Märet Jonsdotter – introduced her to Satan. Since that night, Gertrud often visited Satan’s island, Blakulla (also spelled Blockula), where she encountered both demons and angels, milked cattle with familiars, and took children to meet Satan.

Gertrud’s confession was the start of the Mora witch trials – called “Det Stora Oväsendet” (“The Great Noise”) and lasting almost a decade – and led directly to the death of Märet. Many of the initial accusers were also children claiming to have visited Blakulla, partying with and seeing both demons and angels. As stories and accusations spread through parishes, one trial became a hysteria.

Among the hysteria was the witch trial in Mora, where sixty people were put on trial in August 1669. In front of a crowd of 3,000 spectators, the accused – including children – were interrogated. Within their confessions, children admitted to engaging in transvection (magical levitation) to get to Blakulla, belonging to the Devil and participating in his rituals, and committing maleficia (malignant acts). By the end of the trials, fifteen children were executed and fifty-six were sentenced to corporal punishments or lashings.

The trials spread further, reaching a peak in 1675 at Torsåker – the largest witch trials in Swedish history, where 71 people were executed in a single day. As before, many of the witnesses to the trials were children who accused the witches of abducting them to travel to Blakulla. However, notably, most of the children testified under torture – being whipped, bathed in ice cold water, placed in ovens, or threatened with being boiled in order to give the testimony wanted by priests. Many had lifelong health issues and fears as a result.

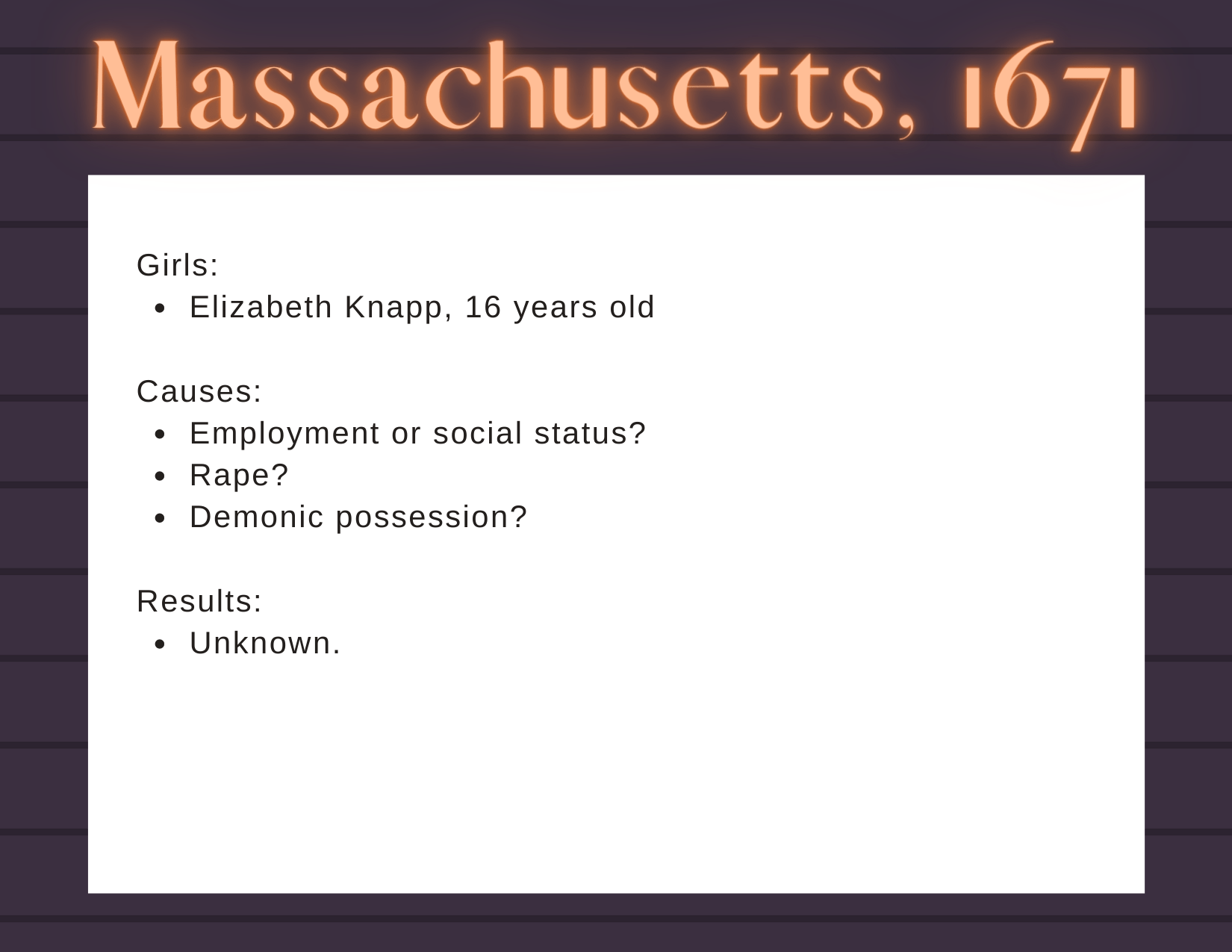

Massachusetts, 1671

In October 1671, 16-year-old servant Elizabeth Knapp began to experience violent physical fits. Elizabeth’s experiences were detailed by her employer, Reverend Samuel Willard, who recorded the weeks of physical fits, weeping, and contradicting stories that occurred. At times, Elizabeth would go completely mute and stupefied or becoming violently physical while enraged or depressed. On one night, Willard records that Elizabeth spoke in a voice not her own, in an episode similar to demonic possession seen in modern-day movies.

Willard also recorded conflicting evidence of why Elizabeth was possessed. Elizabeth often stated she thought she was possessed by the Devil, and that she had entered into a covenant with him even though she never remembered doing so. She also stated that she had sinned greatly, including “disobedience to parents, neglect of attendance upon ordinances, attempts to murder herself and others.” Still more reasons appeared when Elizabeth summoned the Reverend and told him “that the Devil had sometimes appeared to her, that the occasion of it was her discontent, that her condition displeased her, her labor was burdensome to her, she was neither content to be at home nor abroad and had oftentimes strong persuasions to practice in witchcraft…”

Making the case more complicated, Elizabeth hinted at an episode distinctly not demonic. “Once [the Devil] met her on the stairs and often elsewhere, pressing her with vehemence, but she still put it off, till the first night she was taken when the Devil came to her and told her he would not tarry any longer. She told him she would not do it. He answered she had done it already and what further damage would it be to do it again, for she was his sure enough. […] These things she uttered with great affection, overflowing of tears, and seeming bitterness.”

Throughout, Elizabeth never accused any individual in her community – only ever referring to her tormentor as “the Devil.” Was the Devil really visiting her? Was it a trauma response to her employment or possible rape? The answers are mysterious, as Willard’s account ends on January 12, 1672, without stating what became of Elizabeth.

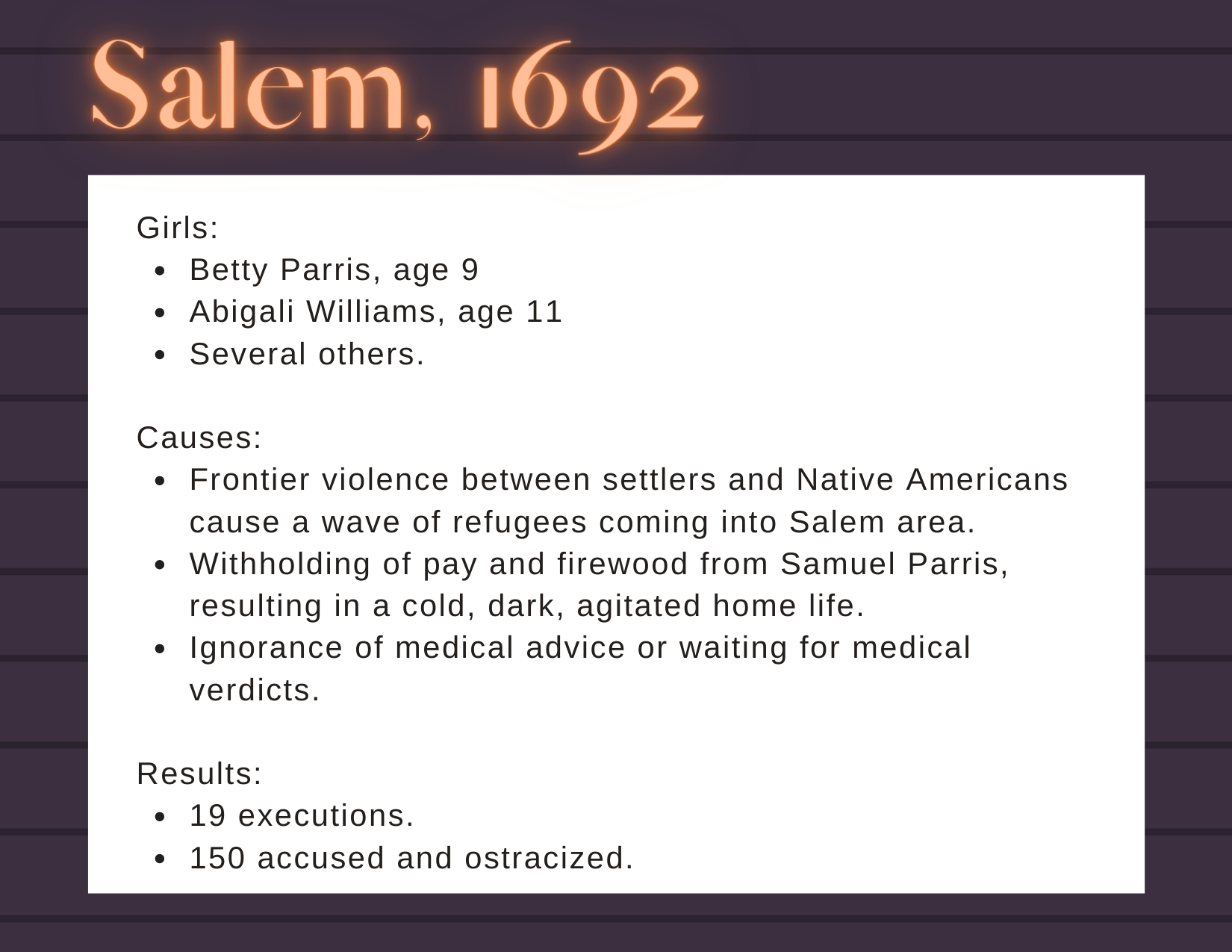

Salem, 1692

Founded in 1636, Salem Village in Massachusetts was a prosperous Puritan village near a thriving port. Yet it had its share of political factions, frequent civil disputes, and ongoing warfare with Native Americans. By 1692, the atmosphere was ripe for a power grab by one of the factions. During what became known as the Salem Witchcraft Trials, two girls took power and demonstrated how “witch persecutions had more to do with the accusers than with the accused.” – Exploring American Girlhood

The Salem Witch Trials began in 1692 at the home of Reverend Samuel Parris, whose 9-year-old daughter (Betty) and 11-year-old niece (Abigail Williams) were living in cramped, dark, cold conditions. Samuel was at odds with the village, who elected to withhold his salary and firewood – creating a cold, agitated household. On January 15, in the depths of winter, Betty and Abigail experienced the first signs of bewitchment – prickling sensations that quickly turned to bites, pinches, fits of barking and yelping, spasms, and paralysis. A neighbor suspected witchcraft, and folkloric superstitions and the agitated atmosphere combined to begin witch hysteria. Betty and Abigail’s neighbors – 12-year-old Ann Putnam and 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard – also began experiencing symptoms. The experiences spread throughout Salem’s young girls.

Despite wanting medical advice, adults in Salem were quickly led by local ministers to believe the fits were caused by Satan. The girls took hold of the belief, accusing adult women – typically older, poor, and single women – of being witches. Accusations, arrests, and examinations ensued as Ann Putnam became the star witness, with other girls taking her lead in telling tales of bewitchment.

Signs that something was amiss were prevalent during the panic. One accuser, servant Marry Warren, recovered and recanted when threatened with beating by her master. Others could only remember their experiences when prompted by Ann Putnam. This was compounded by Salem’s elite, who led trials despite having little to no legal training and relying on what was quickly becoming largely outdated advice on witch hunting. Despite concerns voiced by Salem’s own citizens, the Salem Witch Trials lasted over a year and resulted in 19 executions, 150 accused and ostracized, and an economy in ruins.

Derived from Chapter 7, “Samuel Parris Archaeological Site, Danvers, Massachusetts, 1691” in Exploring American Girlhood in 50 Historic Treasures by Ashley E. Remer and Tiffany R. Isselhardt.

Curatorial Essay

What roles did girls play in witch trials and how did those roles change over time?

The height of European witch hunting began around 1450 and lasted to around 1700. Though scholars have commonly believed child witches were only present in the latter half of this period, our case studies show that girls were accused as witches as early as 1525 – just as the witch hunts gained momentum. So girls were always present as victims, accusers, and accused.

Part of the reason for this misconception is that historical records are often written by the victors – in this case, male authorities reporting on the trials – and we have very little, if any, direct accounts from accused girls. When trial accounts were written, they could be biased – making the trials seem more sensational than they actually were – while also neglecting to record the names and ages of all the accused.

Looking at girl witches offers us a rare viewpoint on Early Modern childhood. Setting aside whether magic was real, the accounts of girls victimized and accused show that girlhood was a period of tension – not quite adults, yet expected to be as moral and religiously fervent as adults. In Navarra, two young girls wanted to be witch hunters and got their wish. In Basque, stories of French witch hunts spurred fear and an influx of immigrants, heightening economic tensions and bringing the overzealous Spanish Inquisition to the region.

Some accounts provide windows on specific girls’ experiences. At Pendle, Alizon and Jennet showcase both the power little girls thought they might have as descendants of folk healers and the tension between wanting to be “good little Christians” – and wanting to protect family members from being accused. Elspeth Reoch of the Orkney Islands showcases the girlhood trauma – possibly sexual abuse and rape – that lead to her ostacization and subsequent labeling as a witch, even though none of the men who perpetuated violence on her were ever accused. Other accounts showcase the effects of religious and civil war (Germany), environmental disaster (Vardo), illness (Hartford), and intercommunity conflict (Salem) – all of which were blamed on witches.

What does this leave us with? Witch hunts were as localized in their reasons as they were widespread in practice, turning overarching social anxieties into local outburst of paranoia, fear-mongering, and blame games. Some historians claim these to be what “separates us from the past” (Roper), but we take a different opinion. Are these fears and responses truly so different from what we do today? How have European witch hunts been brought into our world? And why do we continue to blame girls?

Tompkins Harrison Matteson, Examination of a Witch, 1853 Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum.

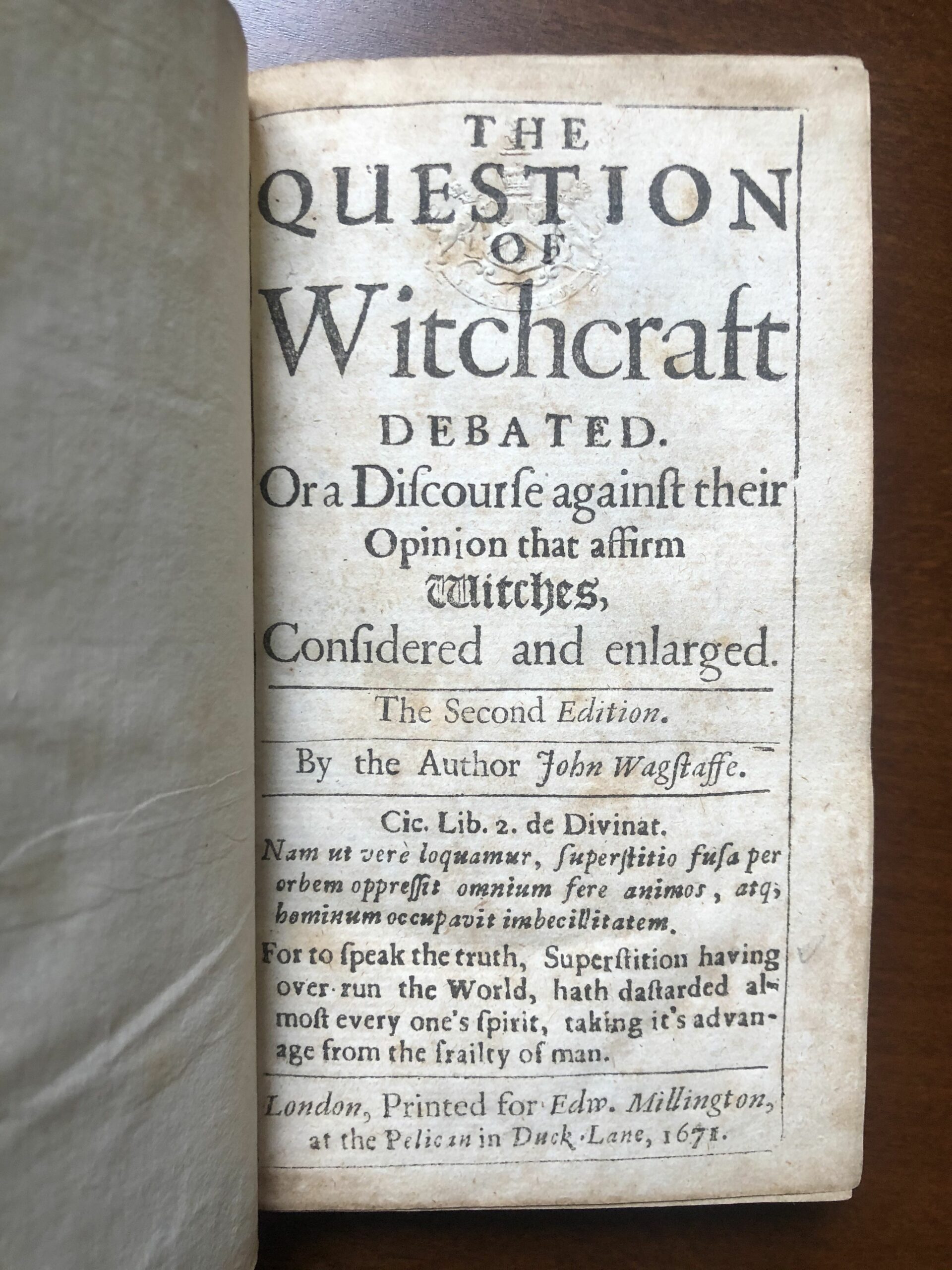

Title page for The Question Of Witchcraft Debated : Or A Discourse Against Their Opinion That Affirm Witches, Considered And Enlarged. (Includes Philopseudeis [Lovers Of Lies] : A Dialogue Made By The Famous Lucian), by John Wagstaffe, Lucian Of Samosata, Sir Thomas More. Image courtesy Biblio.com

Abrupt Endings

By the 1740s, witch hunts were no longer a main figure of life. Over the previous 50 years, societal changes through Europe and its colonies dismantled the beliefs in witches – relegating it back to the realm of folk belief.

Why? The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft (2013) states that the decline happened due to an increasing reluctance to prosecute witches, many acquittals of accused witches, and the repeal of laws that authorized the prosecutions. But looking at the stories of girl witches – particularly ones from the 1690s onwards, there are other forces at work.

Islandmagee, Ireland, 1710

In 1710, 21-year-old Laurien Magee was one of eight women accused of practicing witchcraft. It began with Mrs. James Haltridge claiming that 18-year-old Mary Dunbar was possessed, and Dunbar then accused the eight women of attacking her and causing possession. The women were tried by two High Court judges, who differed on their opinions of the accused – one wanted them acquitted because they were good Christian women, while the other urged conviction. The women spent a year in jail. We do not know what happened to them after that year – some sources say they were executed while others say they were released.

Huntingdon, England, 1716

Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth Hicks lived in Huntingdon. Sometime before 1716, Mary supposedly became a witch, making a pact with the Devil and using her powers to torment her neighbors with illness, fits, and vomiting. She targeted neighbors with whom she had quarreled, including a Mr. Adams whom she used a wax image to inflict burns and pain.

Mary also convinced her daughter, Elizabeth, to become a witch. While watching a ship at sea with her father, Elizabeth caused a storm that wrecked the ship. She later destroyed an entire field of corn. Her father asked Elizabeth about these new abilities, and Elizabeth claimed that her mother had taught her. The father reported them. Mary and Elizabeth were arrested, tried, and hanged. They were the last witches executed in England.

Augsburg, Germany, 1723 - 1729

Over six years, at least twenty children claimed to have been seduced by the Devil. They committed acts of “malefice” in the city, and claimed they had been led by an old woman. The children put glass splinters, teeth, and “diabolic” powder in their parents’ beds; they fought with one another; and they committed “indecencies” with each other. Most of the children were from middling craft families, such as cattle-butchers, brandy-sellers, brewers, and innkeepers.

The parents begged authorities to imprison their children. Twenty children, aged 6 to 16, were imprisoned – most kept in solitary confinement until some begged to die. A year later, the children were transferred to a hospital that “had more warmth, cleanliness and light.” The children were kept there for five years before being released.

Düsseldorf-Gerresheim, Germany, 1738

Though individual witch trials continued, trials which involved larger groups of witches declined drastically. Several factors influenced this decline, including differing opinions by prosecutors and community members, recognition that childhood fantasy and reality are not always distinct in the minds of children, and recognition by authorities that sometimes “witch behavior” was more reflective of a community’s inability to deal with change. Larger factors at work included:

- Clergy and intellectuals speaking out against the trials, starting in the late 1500s. A notable publication is John Wigstaffe’s The Question of Witchcraft Debated (1669), which used theological arguments to hinder beliefs in witches.

- Changes in leadership as old kings died and new ones ascended, often not with the same priorities and beliefs as their predecessors.

- Fairer treatment in court as trained magistrates insisted on overseeing cases.

- Repeal of laws against witchcraft in the early 1700s (though some were not fully repealed until the 20th century).

- Accusers who later claimed they “faked” the evidence, such as Ann Putnam in the Salem trials.

- Economic effects on areas where many were accused and executed, leading to population declines, loss of family and community stability, and loss of labor to ensure economic prosperity.

Another factor relating to the decline of witch hunts – particularly beliefs in child-witches – was the “innocent child” stereotype. In the 1700s, children came to be seen as “pure and innocent and in need of adult protection.” As seen in very late cases of child-witches, the beliefs that children could be independent actors persisted – but the cases against them provided proof that children could misconstrue adult beliefs – religious or otherwise – into fantasies that looked like witchcraft but really expressed children’s confusion about adult behaviors. Over time, this recognition contributed to the “innocent child” stereotype – no longer was a child influenced by the Devil; rather, children’s misbehavior was attributed to misunderstanding of adulthood. This proved the need to protect children – notably from concepts deemed too “adult” or “evil” – and persists to this day. No longer held responsible, children’s behaviors previously attributed to witchcraft became symptoms of disease, parental neglect, and lack of education.

“What never died out completely, however, was the demonization of those considered “other.” It resurfaced, along with witch hunting, in postcolonial Africa, most likely, [historian Ronald] Hutton suggests, as a response to the process of modernization after independence. Even today, we see witch hunts breaking out in different parts of the world among cultures most fearful of change.”

Legacies

Though witch hunts ended in Europe in the 1700s, beliefs about witches spread through colonization to Africa, Asia, and South America. European Christianity merged with local folk beliefs, creating regional variations in witch-hunting that often target women and children. Notably, child witches became a tool of colonization – applied to non-European cultures to subjugate populations. Used by pastors and churches to force conversion or split children being converted from their parents (who held onto indigenous beliefs), witchcraft was used to enforce Christian religion and ingrain the idea that anything indigenous is bad and that if someone is struggling, it’s because they’re not a good Christian or are possessed by the Devil. These beliefs have persisted to modern times.

Child witches tend to occur in areas where folk beliefs in magic are still prevalent, but are also rooted in political and social dilemmas. Notable areas include India, where nearly 150 suspected witches are murdered each year; Tanzania, with 1,000 female witches accused and murdered each year; and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where as many as 50,000 children currently live as street orphans because they have been accused of witchcraft.

Credits

This exhibition was curated by Tiffany R. Isselhardt, Program Developer. Title images created using Canva.

References & Further Reading

Finding Girl Witches

Titus Livius, Book Eight – https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0155%3Abook%3D8%3Achapter%3D18

https://news.uark.edu/articles/23732/historian-argues-confucianism-emerged-after-reign-of-emperor-wu

Hutton, Ronald. The Witch: A History of Fear from Ancient Times to the Present. Yale University Press, 2017.

Howe, Katherine (ed.) The Penguin Book of Witches. Penguin Group, 2014.

Hall, David D. (ed.) Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England: A Documentary History, 1638-1692. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1991.

Renaissance Changes

Kramer, Heinrich. Malleus Maleficarum. Translated by Montague Summers. London: J. Rodker, 1928.

Willis, Deborah. “The Witch-Family in Elizabethan and Jacobean Print Culture.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 13, no. 1 (2013): 4–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43857911.

Case Files

“Samuel Parris Archaeological Site, Danvers, Massachusetts, 1691” in Exploring American Girlhood in 50 Historic Treasures by Ashley E. Remer and Tiffany R. Isselhardt.

Mather, Cotton (1862). The Wonders of the Invisible World. Kindle File: A Public Domain Book. p. Loc 2176–2224.

MacDonald, Alexander; Robertson, Joseph (1840), Miscellany of the Maitland Club: Consisting of Original Papers and Other Documents Illustrative of the History and Literature of Scotland

Miller, Joyce (2008), “Men in Black: Appearances of the Devil in Early Modern Scottish Witchcraft Discourse”, in Goodare, Julian; Martin, Lauren; Miller, Joyce (eds.), Witchcraft and belief in Early Modern Scotland, Palgrave Macmillan UK, ISBN 978-0-230-59140-0

Robbins, Rossell Hope, ed. (1959). “Mora Witches”. The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. Crown Publishers. pp. 348–350.

Rojas, Rochelle E (2016). Bad Christians and Hanging Toads: Witch Trials in Early Modern Spain, 1525-1675. Dissertation, Duke University. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10161/13429.

Steed, Alexandra C. “No One Expects the Spanish Inquisition: Witchcraft Trials in Basque Spain and Southwestern Germany.” Honors Theses, Union College, Schenectady, NY, 2017.

Walinski-Kiehl, Robert S. “The devil’s children: child witch-trials in early modern Germany,” Continuity and Change 11(2), 1996: 171-189.

Curatorial Essay

Roper, L. (1991). Witchcraft and Fantasy in Early Modern Germany. History Workshop, 32, 19–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4289099

Ben-Yehuda, N. (1980). The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist’s Perspective. American Journal of Sociology, 86(1), 1–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2778849

Abrupt Endings

Lyndal Roper. “‘Evil Imaginings and Fantasies’: Child-Witches and the End of the Witch Craze.” Past and Present 167 (May 2000): 107-139.

Brian P. Levack (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Oxford Handbooks, 2013.

De Angelis, Lauren. “Witch Hunting in 16th and 17th Century England,” The Histories 8(1).

Legacies

“Child witch hunts in contemporary Ghana” by Mensah Adinkrah, https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.chiabu.2011.05.011

“Child witchcraft accusations in Southern Malwai” by Erwin Van Der Meer, https://search.informit.org/documentSummary;dn=388872666173510;res=IELIND

https://www.encyclopedia.com/children/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/child-witch

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=44f8a8cc132b4b76b8aedb8672580edf

https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NEWSEVENTS/Pages/Witches21stCentury.aspx

https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/why-is-papua-new-guinea-still-hunting-witches/

https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/probe-thrashing-witchcraft-accused-starts/

https://globalnews.ca/news/8377983/toronto-teens-witchcraft-congo/

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-47053166

https://www.dw.com/en/indias-witches-victims-of-superstition-and-poverty/a-49757742