As humans, we are united by having bodies to travel through our lives and faces to communicate with others. However, we are individuals with different personalities, individual will, and choices about how to express that individuality.

We conform, we rebel. We want to fit in and we want to stand out.

When did we start adorning our bodies? Why do we paint our faces and pierce our ears? Why do we decorate ourselves?

Is it about ourselves or others? Individuals or society?

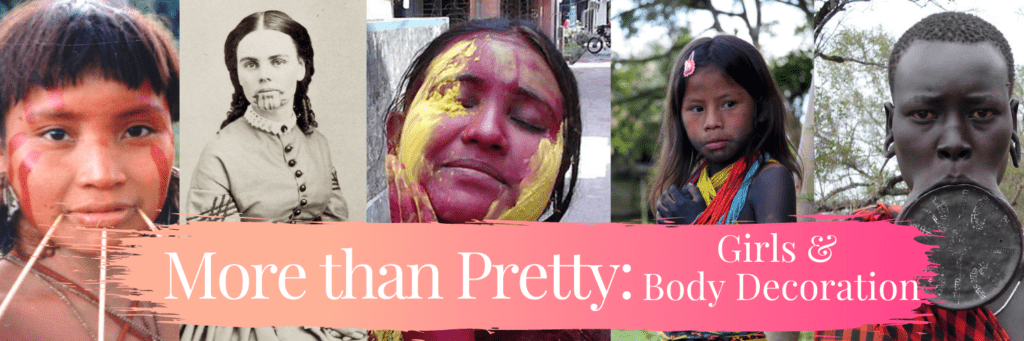

Welcome to More than Pretty: Girls and Body Decoration. We’ll look at how girls present themselves to be looked at across time and space. This exhibition focuses on the head–including the neck, face, and hair. Decorative practices are so varied around the world that we do not intend to be comprehensive. Instead, it is to start conversations, and is open for further contributions.

History

It is likely that from the first time humans added water to a smashed plant or mineral pigment, we put it on our bodies–especially our faces–for a whole host of reasons. To encapsulate the entire history of body decoration from around the world is beyond the scope of an exhibition. Instead, there are a selection of designs, methods, and occasions included in this exhbition, primarily based on the materials available to us. It is difficult to find more contemporary images that are free to use, but there is an abundance of historical information.

Additionally, the blogs below detail hygiene and body decoration practices in a range of time periods. More blogs will be added as research is completed.

More Than Pretty: Victorian Era 1837-1901

The Young Queen Victoria, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1842). This blog is part of series linked to our exhibition, More than Pretty, which looks at body decoration of girls throughout history. Check out the exhibition here. The Victorians are synonymous with makeup....

More Than Pretty: Regency Era

Louisa Montagu, Viscountess Hinchingbrook, later Countess of Sandwich (1781-1862) as Hope. Thomas Lawrence. Oil on canvas, c. 1804. This blog is part of series linked to our exhibition, More than Pretty, which looks at body decoration of girls throughout history....

More Than Pretty: Georgian Britain (1714-1830 CE)

Portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, by Thomas Gainsborough. Oil on canvas c.1785-87. Chatsworth House private collection. This blog is part of series linked to our exhibition, More than Pretty, which looks at body decoration of girls throughout history....

More Than Pretty: Stuart Britain (1603-1714 CE)

Princess Elizabeth (1596–1662), Later Queen of Bohemia, by Robert Peake the Elder (ca. 1606). Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art. This blog is part of series linked to our exhibition, More than Pretty, which looks at body decoration of girls throughout history....

More Than Pretty: Tudor England (1485-1603 CE)

Elizabeth I when a Princess c.1546. Attributed to William Scrots (active 1537-53). Oil on panel.Royal Collection Trust (Queen's Drawing Room, Windsor Castle), RCIN 404444 This blog is part of series linked to our exhibition, More than Pretty,...

More Than Pretty: The Middle Ages (1066-1485 CE)

Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of a Lady, c. 1460, oil on panel, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.44 This blog is part of series linked to our exhibition, More than Pretty, which looks at body decoration of girls throughout history. Check out the...

Daily Rituals

From the time we wake up and greet the day to when we go to sleep, there is a process we follow, whether we realize it or not. When we don’t, it can feel unsettling. Mostly, these processes involve some kind of washing to cleanse from our bodies either the dirt of the day or the veil of sleep.

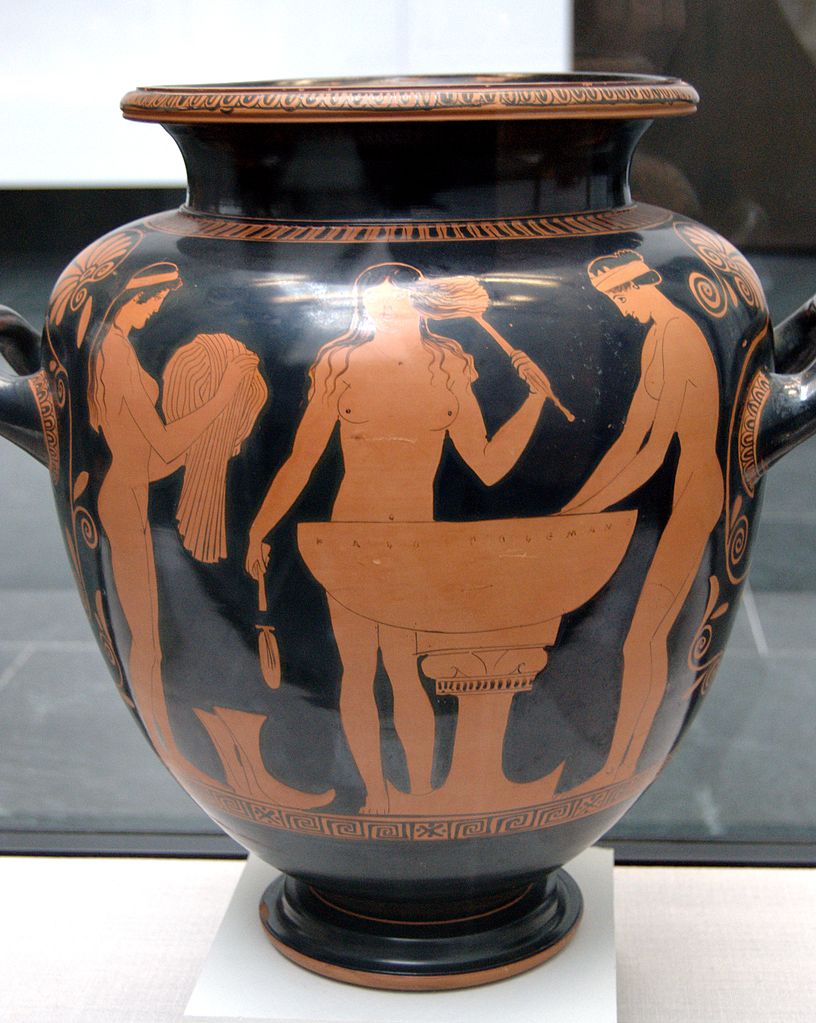

Three young women bathing. Side B from an Attic red-figure stamnos, 440–430 BCE. Staatliche Antikensammlungen

Washing and Bathing

The Ancient world has well documented washing practices.

Ancient Egyptians washed multiple times a day, usually in water basins using a soap made from ash and clay. They believed that the cleaner and more well-oiled a person was, the closer they were to the gods. This extended to the afterlife, with hygiene and makeup items buried with the dead.

Ancient Greeks developed the first known bathing complexes and showers. The Romans adopted the Greeks’ ideas, with numerous public bathing houses featuring running hot water, steam rooms, and cold plunge pools. Baths were for cleanliness, wellness, socializing and business.

In Asia, bathing culture began in Buddhist India, where priests would bathe to remove bodily and spiritual impurities. This practice spread throughout Buddhist societies in China and Japan. Bathing became central to healing rituals.

In Europe, the first mechanical shower was invented in 1767, around the time people began to realise good hygiene contributes to good health.

During the 19th century, the idea of public baths became popular again as a way to stop the spread of disease. As modern advertising took off, items like soap and deodorant became more a part of people’s daily routines. Cleanliness became a symbol of human progress, breaking from old fashioned ideas of the past. By 1900, most families would have at least had a weekly bath and washed their faces and hands daily.

In Europe, North America and Australasia, daily showers are a normal routine for girls of all ages. A wide variety of face cleansing and moisturising products are available, with a recent focus on handmade, natural, and locally sourced beauty products.

Climate also plays a role. In colder climates like Sweden and Russia, girls visit bathhouses and saunas with friends or family, typically once a week. In warm and humid climates like Central and South America, girls shower once or twice a day. There is less choice in products to use, with a preference for bars of soap.

In Africa and the Middle East, baths are more common than showers. Bathing is usually once daily, except in Muslim communities where girls bathe twice a day. There is a big emphasis on natural products, especially those of local or traditional origin. Exfoliation is also important. In the Middle East, girls also attend the hammam, or communal sauna, with their families at least once a month.

Many Asian cultures are very hygiene conscious. Girls bathe or shower daily, with emphasis on full body exfoliation. In Korea, girls visit the sauna once a month with their families, while girls in India tend to prefer showers.

Hair Care

Hair care today is based on many 20th century inventions. In the 1930s, Dr. John H. Breck invented the first shampoo, made popular by a successful advertising campaign. Before that, Castile soap bars were the popular option for hair washing, and have recently made a resurgence (with new formulas).

Like other bathing rituals, practices vary based on a girl’s location.

In Europe and North America, the average girl washes her hair every second or third day. There are a variety of products to choose from, with recent trends towards plastic-free, natural, and locally sourced products. Girls in northern climates also use moisturizers, especially during the winter months.

In South America, girls wash their hair every day or every other day. In Brazil, girls use as much as three times more hair products than their American counterparts. In particular, keratin treatments are common to combat the climate’s effect of producing dry and brittle hair. A large disparity of wealth exists in most South American countries, meaning that while a large selection of hair products are available, most girls and their families cannot afford more complex treatments.

In Asian countries, girls wash their hair daily. However, in India, girls wash their hair every 2 or 3 days. They commonly condition their hair with coconut oil and flowers, washing it the next day. In India, Hindu girls keep their hair in two braids, which is a sign of beauty and purity.

Girls in African countries wash their hair less frequently than in other areas. They also rely more on traditional and natural methods. In Ethiopia, raw unsalted butter has been used for centuries to nourish dry hair once a week, massaging it into the scalp and leaving it overnight. They also use butter with ochre to dye their hair a deep terracotta colour before putting it into twists. The intricate hairstyles girls receive do not make washing easy, so many sleep on wooden headrests to preserve their hairstyle.

Girl Arranging Her Hair, 1886, Mary Cassatt, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

A miswak teeth cleaning stick. محمد الفلسطيني, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Free dental care for children at the Guggenheim Dental Clinic, New York City: 4 children being taught the correct use of a toothbrush by a dental hygienist. [Between 1940 and 1945?] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Teeth Brushing

The first record of an item used to brush teeth was a twig, with the ends frayed to soften the wood. These were used by the Ancient Egyptians and Babylonians around 3500 to 3000 BCE. The Ancient Chinese also used wood to clean their teeth–by chewing it. These chewing sticks were made from aromatic twigs, which were thought to freshen the breath as well as clean the teeth.

The oldest toothpaste found comes from the Egyptians and dates from around 5000 BCE. The Ancient Chinese, Greeks, Indians, and Romans all used variations of toothpaste with different ingredients. These included burnt eggshells; crushed oyster shells; powdered ox hooves and pumice; powdered charcoal and bark; ginseng; herbal mints; and salt. You can buy herbal and mint toothpastes as well as baking soda and coconut oil today, all promising fresh breath or whiter teeth–not unlike the ingredients used throughout history.

Toothbrushes and toothpaste in these forms continued to be used right up to the 17th century, when toothbrushes with bristles and handles were first used. Our modern toothbrushes were deisgned from these.

The modern toothbrush in the Western world is now plastic, and sometimes electric. Bamboo toothbrushes are growing in popularity as a more sustainable option. But many cultures around the world use the older techniques above to clean their teeth. These options are also sustainable, using natural ingredients. Muslim communities throughout Africa, Asia, and Malaysia use twigs from the Salvadora persica tree, which is high in naturally occurring fluoride. These twigs are known as siwak or miswak, meaning “chewing stick.” In India, toothbrushes are similarly made from trees, mainly from cherry, mango, cashew, or coconut wood. Imagine the smell from the wood, delicious!

Makeup

Do you remember the first time you used makeup? In many parts of the world girls to start experiment with makeup at a young age, either with friends or family members. So what exactly is makeup? It is a range of cosmetics, such as mascara, eye shadow, and lipstick, worn to add color and drawn attention either to or from the area it is applied to. With so many girls in the modern world wearing makeup, what are their reasons for doing so?

Makeup has a long tradition throughout history of being worn by both women and men. It was very trend-based and transformed the wearer into the ideal look of the day, which is similar to what we do now. As the Industrial Revolution changed the roles men and women occupied in society, most men stopped wearing makeup and it became something primarily women and girls wore. Some of the reasons makeup is worn today are the same reasons that have existed throughout history. Let’s explore these: hierarchy, religion, cultural traditions, and religious or spiritual reasons.

Hierarchy, meaning a social structure based on different levels, has existed in societies for millennia. In the Ancient world, makeup was one of the ways to display social status. It was also during this time that some forms of makeup and colors developed negative reputations and saw the first formal regulations about makeup coming into force. Lipstick was mainly worn by sex workers in Ancient Greece, who were a readily accepted group in society. Today this connotation has been transformed in the names of lipstick colors. The red colors have more sexualized names, like ‘siren,’ ‘sultry,’ and ‘bombshell;’ moreso than those of pink or orange shades. Lipstick in general uses a lot of words linked to attraction and desire in their names.

Religious, spiritual, and cultural traditions have always played an important role in why girls wear makeup. Cultures throughout history found practical and medical benefits from wearing it. Ancient Egyptians wore kohl around the eyes to protect from sun glare, to keep dust out, and for other antibacterial reasons. Today many makeups include moisturizing agents or sunscreen for the same reasons. Religious and spiritual beliefs have also influenced what types of makeup can and cannot be worn. This impacts individuality and personal expression. For example, for some Muslim girls and women who wear hijabs (hair covering) or niqābs (hair and face covering) use makeup as a way to express themselves, whether or not anyone can see it. In this way, makeup is for girls and women themselves, mainly in women-only environments.

When asked, confidence is one of the main reasons many girls give when asked why they wear makeup. In many places, the ideal of feminine beauty was popularized in the 19th century and has continued into the modern day through marketing. Advertisements frequently mention covering up undesirable features, like uneven skin tone or blemishes. Makeup is sold with the promise to achieve perfection in looks, and thus to feel as confident as they appear in the ads. Many girls and women do not feel comfortable leaving the house without makeup. Expression of self and experimentation with how we present ourselves are also often given as reasons why girls wear makeup.

Whether they have access to a wide variety of makeup or even a few shades, girls experiment with different looks and ways of showing who they are, now more than ever. Individuality, however, isn’t the only reason girls wear makeup. Advertising encourages girls to believe one of their primary functions is to be pretty and appealing. Beauty ideals vary from culture to culture, but according to several studies, there are some universal markers of attractiveness. Facial symmetry and an even skin tone imply good health, while youthfulness denotes fertility. Girls and women listed eye makeup in particular as enhancing youthful looks and facial beauty.

So what are the most popular make-up trends today?

It depends on where you live. In most Western countries, having a tan and an even skin tone is desirable, with an emphasis on eye makeup. Skincare is more important than makeup, which is becoming more minimal, and hair care is growing in popularity, with masks and oils becoming a part of girls’ routines.

In Asian and South American countries, there is an emphasis on wellness so being healthy is most important. Skin bleaching products are common in Asian and some African countries, where girls are taught from childhood that lighter skin is more beautiful. Long silky hair is the ideal, with hair masks and oils having been used by generations of girls. The hair products are often natural and locally sourced, something traditionally used. Girls often care more about skincare routines than makeup, which is minimally applied, with an emphasis on using ethical and natural products.

By far the most popular trend around the world right now is the Korean multi-step routine. The daily routine includes a water-based cleanser, toner, exfoliator, essence, serum, sheet mask, eye cream, moisturizer, and sunscreen. For South Korean girls, a skin care routine is a vital part of daily life from childhood, with a focus on curing issues, not covering them up with makeup. All this means that primers, sprayable toners, BB cream, and lip products with natural moisturisers are the must have products, with makeup being minimal–usually eye liner, mascara, and lip gloss.

Makeup in Decora Fashion, Harajuku, Tokyo

By Dr. Megan Catherine Rose (UNSW Sydney, Australia) and Haruka Kurebayashi (Decora Fashion practitioner, Harajuku); Japanese version by Rei Saionji (Writer, Japanese regional culture researcher, Cabinet Office Regional culture and economy revitalisation evangelist)

“But regardless of the cocoon spun in secret, the fluttering motion of ribbons and grills asserts her “girlhood”. The girl may try to avoid contact with the outside world when in her self-contained, inwardly converging state; nevertheless, her constant swaying and fluttering provokes and attracts the gaze of others.”

Figure 1. Pika Suzuki Paisen &Takenoko Horuzo

Japanese Version 日本語

デコラファッションにおけるメイク (東京 原宿)

ミーガン・キャサリン・ローズ博士(オーストラリア UNSWシドニー大学)、

紅林大空(デコラファッション実践者 原宿)

日本語版:西園寺怜(著述家・日本地域文化研究家・内閣府地域活性化伝道師)

繭の中でひっそり紡がれる「少女の時」の他方では、リボンやフリルのひらひらとゆれる動きが、「少女の時」を主張している。「ひたすらに内に向って取敏し、外界とかかわりなく自足するありようと、絶えずゆれ動き、「ひらひら」と他者の目を誘う挑戦発的なありよう」。

本田和子

(1992)異文化としての子ども, 東京、 筑摩書房、 p. 151

デコラファッションとは、東京の原宿周辺で生まれた、顔や身体を「物」で飾ることを特徴としているファッションであり、年齢や性別に関わりなく愛されているが、特に自らを「女の子」と称する10~20代の若い女性にその実践者が多い。デコラファッションは、世界的に「原宿に生息する女の子」の延長線上にあるポップカルチャーとして捉えられているが、デコラ系のファッショニスタたちが自らのことを話す機会はあまり多くない。我々は、彼女たちの話やどのようにデコラファッションが創造性やノスタルジーな気持ちを表現しているかについて皆さんにお伝えしたいと考えている。

ビビットな色を多色使いし、しかもそれぞれが調和していない色を意図的に組み合わせる。そして、アクセサリーを重ね付けし、ハンドメイドやチープな小物を使ってスタイリングする。これがデコラファッションである。さらに特徴的なのは、多種多様の小物を顔や身体に直接付けることである。(写真3:ピカ鈴木とたけのこほるぞーのファッション)デコラファッションの実践者は、学校や勤務先などのドレスコードがある場所には服装を変えている。なぜならば、彼らは、デコラをそれ以外の場所で楽しむ娯楽と捉えているからである。彼女たちにとって、デコラは他人からの注目を浴びるための行動ではなく、クリエイティブ且つ楽しい趣味であるのだ。

興味深いことに、デコラ系のメイクが、一般的な少女が持つ「おしゃれ」やアートに対する感覚と路線が交わることもある。多くのメイク術と同じように、デコラ系のメイクも時代の流れに応じて変化してきたのである。2000年代後半から、日本ではカラーコンタクトレンズやつけまつげがブームとなった。これは、当時の日本におけるメイクの流行が多様化した一例である。ノマミは目の虹彩の色と大きさを変えるために青色のコンタクトレンズを装着し(写真1)、紅林も同様にカラーコンタクトを装着し、さらに星を付けてデコラティブにしている(写真5)。この点については、デコラファッションが、日本人が少女に対して抱いている美しさの基準を多様化させたと言えるだろう。しかしながら、とてもニッチな美の表現方法も作り出したのであった。顔にシールやバンドエイド、小さなおもちゃを貼り付けるという、一般的な感覚では模倣しにくいメイク術を生み出した。例えば、(写真2)のチャラは、顔にシールを貼るだけでなく目玉をつけ、ぴんきゅあは、化粧用の糊でカボッションカットの宝石を付けている。デコラファッションでも一般的なメイク術に使われるメソッドが使われるが、メイク術に取り入れられる「物」がユニークであり、一般的なメイク方法とはかけ離れたものであったりする。

デコラ系の人々は、自分たちを一つの「グループ」もしくは「ジャンル」として認識しているが、その一方では、自らのオリジナリティーを追求することをファッションの真髄としている。チャラや紅林が身につけているビーズのアクセサリー(写真2、5)のように、デコラ系の人々は、アクセサリーを自作することもある。6%DOKIDOKIのような店舗がデコラファッションの需要に応えているが、デコラ系の人々が、特定のブランドや店舗に依存することはない。彼女たちが自らの顔に施す装飾はアートであり、ユニークなアイテムを組み合わせることによって身体をカスタマイズしているように思われる。彼女たちがデコラファッションに取り入れている物は、「ダイソー」や「クレアーズ」などのディスカウントストアや、子供のおもちゃ店などで自分が見つけた物である。デコラ系の人々は、何らかの形で自分に共鳴するような物を選ぶ。身に付けるアイテムの選定プロセスは、「メゾピアノ」や「たまごっち」などの商品を集めるというような、幼い頃に自分がした遊びに対する郷愁感に大きく影響されている。幼少期に慣れ親しんだ物を身につけるということは、子供の頃に感じた心からの喜びや幸福感を表現するための方法である。これは、幼児退行や、大人としての責任から逃れるためのものではなく、幼い頃の幸福感を自分たちの現在の生活に取り込むためのものである。故に、デコラファッションは自分自身や自己の記憶、創造性を具現化するものであると言えよう。

筆者について

ミーガン・キャサリン・ローズ博士:オーストラリアのUNSWシドニー大学の非常勤講師。東京のカワイイコミュニティーとゴシックコミュニティーに精通している。

紅林大空(くればやしはるか):アーティスト・ミュージシャン・モデル・原宿のデコラファッション実践者。原宿カルチャーを世界に広めることに意欲を持っている。

Decora Fashion (デコラファッション) refers to a mode of dress associated with the Harajuku area in Tokyo, Japan, where the practitioners adorn their face and bodies with found objects. While anyone of any age and gender can wear Decora Fashion, it is typically practiced by young women in their teenage years or twenties who refer to themselves as “girls”. While the Decora Fashion has captured the imagination of popular culture internationally as part of the “Harajuku girl” fantasy, little opportunity is provided for these individuals to talk about themselves. We hope to tell the story of these girls and explain how Decora Fashion is an expression of creativity and nostalgia.

Decora Fashion is a bright and colourful style, characterized by mismatching bright colours, layers of accessories, as well as hand-made and thrifted items. This is then elaborated upon through the extensive layering of objects on the face and body (see for instance, Pika and Takenoko’s outfits in figure 1). Decora practitioners dress differently for work or school where there are dress codes, and view Decora as a fun activity outside of these spaces. From their perspective it is seen as a creative and enjoyable past-time, rather than an attention-seeking exercise.

Decora makeup provides an interesting instance where girls’ beauty practices and artistic agency intersect. Like many beauty practices, the makeup associated with Decora Fashion has been subject to transformation through trends. For instance, since the late 2000s, colored contact lenses and eyelashes came into vogue, mirroring broader cosmetic trends in Japan at that time. In figure 2, we can see that Nomami has used blue contact lenses to change the colour and size of her iris, as has Kurebayashi [in figure 3], with the addition of star shapes. In this regard, Decora Fashion reproduces aspects of broader beauty expectations of girls in the Japanese context. It does, however create a very niche interpretation of beauty, pushing boundaries and disrupting the reproduction of cosmetic processes by adorning the face with stickers, adhesive bandages or small toys as an expression of artistic agency. Chara, [figure 4], for example has not only attached stickers to her face but also googly eyes, and Pinkyua has glued on cabochons with cosmetic adhesive. While elements of mainstream makeup practices are evident in Decora Fashion, the uniqueness of the found objects disrupts and co-opts this process.

While Decora Fashion practitioners identify as a group and genre, the performance of originality is also a core tenant of this mode of dress. Practitioners sometimes hand make their own accessories such as Chara and Kurebayashi’s fusion bead accessories in figures 3 and 4. Stores such as 6%DOKIDOKI might cater to Decora Fashion, but the practitioners themselves do not identify with any one brand or store. The adornment of their faces is seen as an artistic practice, a customisation of the body with a combination of unique items. The found objects used in Decora Fashion are sourced by the practitioner from inexpensive retailers such as Daiso or Claires, or children’s toy stores. Practitioners select objects to wear that resonate with them in some way.

Nostalgia for girlhood culture plays a particularly big role in this process, where the practitioner collects merchandise from franchises from when they were children, such as Mezzo Piano and Tamagotchi. The wearing of these childhood objects is intended to be an expression of the pure joy and happiness they felt as children. It is a commitment to bringing this happiness into their current lives, rather than an attempt to regress into an infantile state or to deny their responsibilities as adults. As such, Decora is an expression of self, memory and creativity.

Figure 5. Pinkyua Momota

Authors:

Dr. Megan Catherine Rose is an Adjunct Associate Lecturer at UNSW Sydney, Australia. She specializes in kawaii and gothic communities in Tokyo.

Haruka Kurebayashi is an artist, musician, model and Decora Fashion practitioner from Harajuku, Tokyo. She is passionate about promoting Harajuku culture worldwide.

GirlSpeak: Decora and Gothic Lolita

Dr. Megan C. Rose talks with guests Kurebayashi and Rei about decora and gothic lolita fashion in Harajuku. From discussing the rise of these fashions as distinct Japanese social phenomena to building a cafe that appeals to decora and gothic lolita audiences, our guests provide unique insights into these subcultures and how girls participate within them.

Eyes

The most common eye makeup teens girls use are eyeliner, mascara, and eyeshadow. Variation on these products have been used for thousands of years, but since the start of the 20th century, there has been exponential growth in the cosmetic industry. Styles have changed markedly each decade, showing how whimsical and trendymake up can be. Watch the videos below for an overview of the last 100 years of styles. Notably, since around 2010, rather than following an overarching trend, the preference has been for individualism–choosing the colors, designs, and methods that girls choose for themselves.

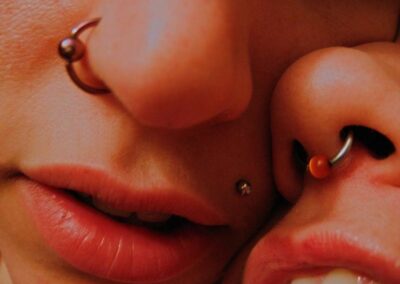

Piercing

At the start of the 20th century, piercing any part of your body was unpopular and an uncommon sight to see. It wasn’t until the 1960s that piercing started to become popular, beginning with the ears. Piercing became more mainstream in the 1970s as the punk movement embraced it and popularized the use of non-conventional studs, using things like safety pins. By the 1990s, body modification in the form of piercing had become widespread, with the nose, belly button, eyebrows, lips, and tongue being added to the traditional ear piercing. Today the most common piercings on the face in order of popularity are: earlobe, nose, ears (other than lobe), tongue, eyebrow, and lip.

So why do girls get piercings?

Prior to the surge in popularity in the 1960s, girls could have gotten piercings for traditional or cultural reasons. Piercings have been used throughout history as a way to show social status, a rite of passage from girlhood to womanhood, to affirm culture or heritage, or for religious and spiritual reasons. Today, there are many girls who receive piercings for these reasons, especially in non-Western cultures.

In the West, piercing has no historical significance. It is a fashion statement, something that has become a normal way to express yourself and your individuality. Popular culture brought certain types of piercings into the mainstream, when girls would get the same piercings as their favourite music star. Once music videos became the norm, piercing became commercialized by the media and more specialist shops started to pop up in every town and city to keep up with demand.

Other motivations for getting a piercing include group affiliation, impulsiveness, and teenage rebellion. Teenage rebellion against parental control in particular has been a major influence in teenage girls getting piercings. The mainstream media has promoted the view that parents do not like piercings in places other than the earlobe, encouraging piercing in other places.

Nose and beauty mark piercings

Nose and beauty mark piercings, ButterflySha (on flickr.com), CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Lip piercings

Lip piercings, Daisy Romwall from Morro Bay, United States, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Surface piercing

Surfacing piercing, next to ear. Maria Casacalenda, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ear piercing is the most popular piercing seen on girls. Throughout the tribes of the world, ears pierced ears certain metals would ward off bad spirits as the girl became a woman. For most of history up to the 1970s, girls got their ears pierced at home. Ear piercing parties became popular from the 1950s onwards. Prior to this time, clip-on earrings were the most common type of earring. By the 1970s, the most popular body part girls and women had pierced was the ears.

Today there are 13 different places you can pierce your ears. Earrings too have changed and become more varied, from simple metal studs to elaborate hoop or dangling earrings with many decorative elements. In India, lavish designs have been common throughout history and remain so today for girls and women.

In many countries today, ear piercing in babies and young girls is an accepted practice. In some places this has become a cultural practice, particularly in Asian countries like India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Laos. Hindu culture is the main religion that has embraced this with girls aged 1, 3 or 5 years old getting their ears pierced in public ceremonies done during sunlight hours. The ritual is never performed in even months or years of age.

Nose piercing has been common in the Middle East, Asia, and Oceania for centuries. Bedouin, Berber, Beja, and Aboringinal peoples have practiced nose piercing for the longest time as a cultural tradition. As these peoples came into contact with other cultures, nose piercing spread throughout the regions in the Middle East and into modern day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. It is still very popular in these areas today. Nose piercings were considered to be beautiful and show social standing through the decorative studs used. In Mughal India, a girl’s nose was pierced on her left side as it was supposed to lessen period pain, and later, childbirth pain. Septum piercings are most popular in the countryside in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, where it shows social, tribal, and religious status in society.

In European cultures, nose piercings were taboo until the 1960s when the hippy movement became popular. The punk movement in the 1970s added to the popularity as it became a symbol of rebellion against conservative values for women. It has slowly become more socially acceptable, but is still widely regarded negatively in a work setting. Nose piercings are very popular for girls and women today across South America, North America, the Caribbean, Australasia, Europe, Africa, and Japan.

Lip and tongue piercing was a later trend. During the 1980s, all things “tribal” (now called Indigenous, in reference to Native peoples in a variety of South American, African, and Asian contexts) became popular. One reason was because of Indigenous people reasserting their right to practice their cultural traditions and native languages. This sparked interest in traditions like lip and tongue piercing, which were both intensely studied and culturally appropriated by non-Indigenous people.

One practice popularized in the 1980s was labret piercing, a cultural practice by Indigenous tribes of North America’s Northwest Coast. Practiced for over 5,000 years, labret piercings involve a variety of piercings between the lips and chin. The piercings were noticed by early European explorers and ethnographers, who thought labret piercing was indicative of social status or gender. In interviews with First Nations members and anthropological research for her Master’s thesis, which constituted the first comprehensive study of the practice, Marina J. La Salle of the University of British Columbia found that labret piercings are “a symbol and expression of social identity that continues to hold significant meaning for the descendants” and current practitioners. She also found that common assumptions about social status and gender do not hold when the tradition is investigated deeply and with living First Nations members.

Through recent analysis like La Salle’s thesis, it is becoming clearer that ‘tribal’ traditions once thought to be simple status- or gender-affirming traditions are much more complex. Cultural appropriation of such traditions has glamorized what is, in fact, a complex, varied, and long-standing cultural tradition.

Body Modifications

In addition to piercing, a variety of body modifications exist across the world. Girls often partake in these as part of cultural traditions.

Ear Stretching

Stretching has long been an important traditional modification for women in many tribes in places all over the world, from North and South America, Asia, Africa, and across Polynesia. For many people, it is the long earlobes and not the jewelry that is considered attractive, as well showing social status. Whilst some are now abandoning the practice, it is still a popular ritual. In some parts of Africa, women start to stretch their lip using a lip plate about six months to a year before marriage. The size of the lip plate can indicate the number of cattle the husband will have to pay for her dowry, or that she gains a higher degree of respect than those who have not stretched. The Mursi women of Ethiopia still practice stretching their ears and bottom lips, the Fulani of West Africa their ears, and the Maasai of Kenya their ears. In South America, the Huaorani tribes of the Amazon start to begin stretching their ears as children using wood or stone. In most countries around the world, there is a minimum legal age for body modifications, like piercing and stretching, so the Huaorani are unique in starting so young.

In the West, ear stretching first came to mainstream fashion trends in the 1990s. It slowly increased in popularity until it peaked in the 2000s when emo music and culture was on trend. Teenage girls most commonly stretched their ears, but would also stretch their tongue or lip. Stretching is permanent, so has not been as popular as piercing, which is easier to cover if you change your mind. Many different materials have been used throughout history to stretch the hole in the skin, but most common today is metal or wooden stretchers.

Mursi girl with stretched ears. Gusjer, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tooth filing/chiselling, Mentawai woman. Unknown photographer via IndoIndian

Tooth Filing

Tooth filing is a beauty and coming of age practice that has been practiced by many Indigenous cultures around the world. Today, there are several cultures still practicing this ritual. Indonesia is one of the few countries where this ritual is widespread across communities on various islands. In Bali, tooth filing is an important event in the life of a girl. It takes place when she reaches puberty, which is signaled by the arrival of her first period. The ceremony usually takes place on an auspicious day and is a lavish celebration. After the ceremony, a father’s duty to his daughter is considered complete. Tooth filing is also practiced in the Mentawai Islands. Although it is a spiritual ritual, it is also a very painful process, as there is no anesthetic involved.

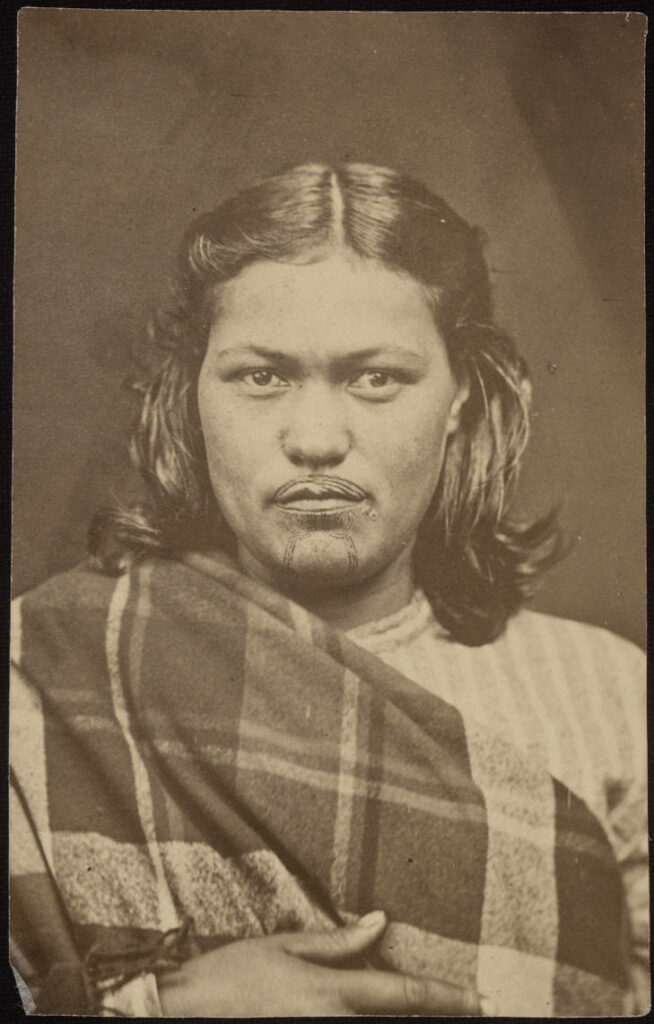

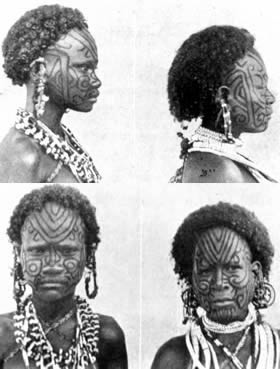

Facial Tattoos

One of the most famous facial tattoos today is tā moko, practiced by Māori people in New Zealand. The technique and the designs used by Māori are unique to the Pacific, with combs and chisels that punctured the skin deeper than their Pacific Island neighbors. The chisels were traditionally made from seabird bones. The process of applying tā moko is a highly skilled one, and all aspects were considered to be tapu (sacred). This included the tattooist, all the tools used in the process, and the space in which it took place. Tā moko is important in the display of status in Māori society and shows a person’s status (mana). While men can have full face tattoos, traditionally women most commonly receive moko kauae on their chins and lips.

Tā moko has helped raise cultural awareness of Māori people worldwide. Women who were tattooed with moko kauae in the early part of the 20th century and lived into the 1980s helped to recover the tradition during the Māori revival of culture. These women provided invaluable knowledge and accounts of the process. Māori women are actively encouraged to have moko kauae if they wish as a means of affirming their Māori identity and the mana of their people.

Unidentified woman with moko kauae, wrapped in a tartan blanket. Unknown photographer. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1618-4

Fulani woman from Mali via Flickr

The chins and mouths of girls of the Fulani tribe in Mali are tattooed, called tchoodi. At puberty, girls receive a black circle tattoo from their mouth to the bottom of the chin. Once a girl is married the top of the mouth is tattooed. It is a long painful process, and the natural ink causes immense swelling to the lips and chin. The tchoodi draws attention to her white teeth and beautiful smile, however, after she is married it indicates that she is unavailable. The ritual is performed only by women and is a rite of passage for girls going into womanhood.

Maisin women of Collingwood Bay, Oro Province. Photograph circa 1900. Via Vanishing Tattoo

The Maisin of Northeastern Papua New Guinea are among the last coastal Papuans to continue facial tattooing. Unlike many other cultures in the area, the tattooing traditions of the Maisin survived the pressures of colonialism and remained a popular custom. The history of the tattoo is mainly told by women, who are also the tattoo artists. The designs are usually simple and placed on the cheeks or edge of the eyes. Tattooing marks puberty for girls, and it is often performed in small groups. It is part of a long ritualized and painful process. But once it is completed, the girl has now been made boresi–beautiful–and has marked her ancestry and ascent into adulthood.

Kila with facial tattoos at Bernard Harbour, Northwest Territories (Nunavut), 1916. Diamond Jenness, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Inuit communities of the Arctic tattooed girls on their foreheads, cheeks and chins. The tattoo designs are usually patterns of straight lines, representing knowledge gathered and accomplishments by the young girls in their life and domestic skills, like how to melt ice for water and make sealskin boots. Christian missionaries during the 19th century convinced girls and women that tattoos were a sin and the practice all but died out. In more recent years, the tradition has been revived with women becoming tattoo artists and tattooing other women in their community.

A Shawia girl stands in front of carpets during a carpet festival in Berber village in the eastern city of Khenchela May 30, 2010. REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra (ALGERIA)

Algerian women have a rich history of tattooing their heritage onto their faces through symbolism. The reasons behind the tradition are varied, but most women living today who received the tattoos as girls say it was considered beautiful and lucky. These tattoos were thought to be a kind of makeup, but also to bring health benefits, particularly increased fertility. The most common age to receive your first tattoo was around age twelve, although some were as young as five. Performed by a travelling female gypsy called an adasiya, the symbols were selected for the girl, often depicting things from nature and the surrounding mountainous landscape. The tradition waned in the 1940s, due to the Islamic prohibition on tattoos, changing ideas about beauty, and the disappearance of the adasiya. Most tattoos seen on Muslims girls and women today are temporary, made of henna.

Efforts of Christian missionaries and colonialism destroyed many cultural traditions of face tattooing during the late 19th and the early 20th century. The Atayal, one of thirteen indigenous groups in Taiwan, practiced facial tattooing until 1895, when Japan began their occupation of Taiwan. As facial tattooing was one of the customs of gender and identity for Atayals, it was banned by the Japanese. Traditionally, Atayal girls were given facial tattoos aged around 15 to 16 years, when they were ready to marry, consisting of a line on the forehead and cheeks, and another line from ear to ear across the lips. Women who had these tattoos were thought to have strong marriages and be the ultimate female Atayal.

Facial tattoos and their historic symbolism continue to influence the Atayal in the modern era. From the 1960s to the 1990s, when tourism started to boom in Taiwan, traditions like face tattooing were revived. Face tattooing in particular became more popular because it was less time consuming than other traditions like weaving and caught the tourist gaze easier. And even more conveniently, they have found a way to temporarily resurrect the past with facial tattoo stickers. These are often worn during festivals and have once again become celebrated as a part of post-colonial Atayal ethnic identity.

Facial tattoos of Atayal women, 2017. Photo via Taiwan News

Scarification

Scarification is a practice that has been around for centuries, although it is not as common as it once was. Many peoples across Africa practice various forms of scarification for both males and females. The scars mark different stages of life and performed during rituals of celebration. The patterns or placement of the scars emphasize social, political, and religious roles of the individual in society as well as beautification. Receiving the scars is a test of courage and personal strength, so girls are encouraged not to cry out in pain. The cheeks and forehead are the main areas scars are applied to girls.

There are many reasons scarification happens. This includes spiritual protection, tribe identification, social markers, medical use, and as decoration. In Ghana, a baby is given face markings as a means of protection from the spiritual world. The Betamarribe tribe who live in the Atakora mountains, which run through Ghana and Togo, give scars for protection, good health, and to mark acceptance by the community. In Sudan, the Dinka use facial scarification to show clan identification, while in the Nuer tribe, girls receive marks on their forehead when puberty starts to show that they are ready for the realities and responsibilities of adulthood.

The traditions of scarification have come up for debate over the past decade. Some young people don’t see it as a modern thing to do and do not see the relevance, nor do they want to go through the harsh and painful process. Others still firmly identify with their cultural histories and say these practices shouldn’t die out or be banned.

Surmi girl of Ethiopia with scarification on face. Photo by Rod Waddington, via Wikimedia Commons

Politics of Decoration

Body decoration is a political act. Whether a girl intends or not, adults often assign her choices social or political value–and, especially for Black and Indigenous girls of color (BIPOC), these values lead to discrimination. Though discrimination based on race or religion is illegal in many places, girls of color or girls who adhere to specific religions often face social, economic, and/or political consequences based on how they decorate their bodies.

Ruby Williams experienced discrimination because she chose to wear her hair naturally. As a Black 14-year-old Londoner, Ruby’s decision to style her hair in an afro–a style traditional to Black culture–led school officials to repeatedly send her home on the grounds that an afro was “too big” and therefore violated school policy. Backed by the Equality and Human Rights Commission, Ruby’s family took legal action. The school opted to settle the case out of court, paying Ruby’s family $8,500 and removing their policy on afro hairstyles. However, the school refused to accept the charge that they discriminated against Ruby.

In 2017, a study by the Perception Institute found that 1 in 5 Black women feel social pressure to straighten their hair for work or school. In these cases, Black women often face “glass ceilings” that block their ability to secure employment or be promoted. Such discrimination may also lead to missing out on education, greater potential for being bullied, and a decrease in feelings of self-worth. For Ruby, she told BBC that she developed depression and anxiety. In late 2019, California and New York became the first US States to ban hair-based discrimination.

For many girls, veils–such as the hijab, niqāb, or burq–are a double-edged sword. For some Islamic girls, wearing these is a symbol of modesty and dignity. Others see it as a sign of women’s oppression, and its eradication a key to their fight for equality. The two sides have often clashed, seeking to find one solution rather than accept an individual’s choice.

In 2018, Anggi Wulan stated in an interview with VICE that she chose to move from wearing the hijab (which covers the hair) to the more extensive niqāb (covering the face and neck) because she wanted to cover her aurat (an Islamic term for parts of the body that must be kept private). She stated, “The most important thing is for me to do the best for myself and for God.” Yet even hijab-wearing women mocked her, laughed in her face, and called her names for her choice, saying it was an “exaggeration” of faith or made her an extremist. Nothing in the Hadith or Quran (two religious texts of Islamic faith) states that a niqāb is required.

Alternatively, some girls are forced to wear veils in regions where religious law is codified into civil law. In Iran, the state heavily controls women’s bodies and forces them to wear the hijab starting at age seven. Women who reject this are considered criminals. Even women who do comply are subject to the “morality” police–state agents who have the power to stop women and examine their compliance to hijab, trouser/overcoat length, and makeup rules. If a girl is found to be in violation of the law, she can be fined or arrested, spend time in prison, and in some cases be publicly flogged or beaten. On a daily basis, girls face random encounters that can lead to bodily or psychological harm. Though some women in Iran may embrace the hijab, there are likely others–especially those who are not of the Islamic faith–that would prefer to have a choice.

Cosmetics are a personal choice with big consequences. Makeup enhances facial contrast–the color difference between different facial features. Higher contrasts are closely associated with femininity (hence, female beauty) in Western cultures. And years of research has shown that attractive people earn more and are more likely to be seen as competent, trustworthy, and healthier.

This stereotype profoundly affects young girls. A 2012 survey by The Renfew Center Foundation, found that girls aged 8 to 18 who wore makeup expressed feeling unattractive or “as though something is missing” if they went bare-faced. Another study in 2008 found that girls who wear makeup often report greater feelings of anxiety, self-consciousness, and a desire to conform than those who do not wear makeup.

Recent years have seen a change in societal norms. The ‘no-makeup’ look has gained popularity, with many saying it is a movement to embrace their more authentic selves. In 2016, a study found that after two weeks of not wearing makeup, women reported a decrease in stress and an increase in self-compassion. In 2019, another study found that natural no-makeup images reduced the impact of idealized images and led to greater self-confidence.

The movement is also beneficial to girls’ faces. Many cosmetics have harmful ingredients because makeup is not well regulated. For example, in 2016, EOS was sued when consumers found that wearing EOS lip balms caused rashes, bleeding, and blistering. It was likely that the “fragrance” ingredient was the culprit.

As the stories about hair, veils, and cosmetics show, girls’ choices in decorating their bodies come with profound consequences. For Black girls wearing the traditional afro hairstyle, like Ruby, it can lead to being forced out of school or the workplace–and experiencing body-shaming that impacts their self-esteem. For girls who choose to wear a veil of any kind, they may face discrimination from those who believe a veil is forced upon them, regardless of the girl’s religious beliefs. And when girls are forced to wear veils due to the crossover of religious and civil law, the decision to not wear the veil can lead to harmful and even life-threatening consequences. Finally, for girls of all races and religions, wearing cosmetics is a personal choice that has been made political through centuries of stereotypes that say a “beautiful” girl is more desirable for all aspects of life. Decoration is political.

Each choice made–to style our hair, clothe our bodies, and show our faces–is a distinct act of conforming or not conforming to society. And in so doing, girls often find themselves in the news.

Makeup Tutorials

I want to start by saying that I love makeup. I used to love getting glammed up when it was safe to leave the house. It’s part of my daily routine and I found that I needed to put some makeup on even while working from home. I learned tips and tricks from YouTube, where I learn about the latest trends and the hottest brands. It’s a form of escapism for me, especially in 2020. I could turn on a 20-minute makeup tutorial and forget about everything else that was happening. I say all this because I want to establish that I do see the value of this branch of the internet. What I think is a big problem is young children creating content for adults.

There are videos online of 12 year olds doing ‘back to school’ makeup tutorials. School is hard enough for kids these days without the addition of the pressure to have the most on fleek eyebrows. The dangers of social media to young people has been well documented, as have the pressures they face in school. This is another unnecessary thing that young children must worry about. Some commentators have pointed out that kids should be kids and shouldn’t be working, which is essentially what YouTube has become for many of them. Others have pointed out that it is similar to beauty pageants for children, with young girls tying their self-worth to their appearance.

Yet it can also be argued that for some children it can become a positive thing. Many content creators and influencers started their channels in their teens and have managed to transition it to a lucrative business for themselves, which has to be admired. They also learn skills that will help them when they choose to leave YouTube, skills like video editing, social media management, and branding, which will open many doors for them.

– Michelle O’Brien

Exploring Body Decoration

Our Pinterest board, More than Pretty, is dedicated to saving images that explore a variety of body decorations and traditions. Explore below or visit the board on our Pinterest.

No shortcode ID foundCredits

This exhibtion was co-curated by Monique Brough and Ashley E. Remer. Special thanks to Tiffany Isselhardt and Katie Weidmann for their assistance, Michelle O’Brien for her contributions, and all those who have participated in researching this exhibition over the years: Phoebe Cawley, Charlotte Jordan, Jessica Yarnell, Charleigh Powers, Niamh Hanrahan, Louisa Yorke, Maria Smith, and Molly Gibb.

We would also like to especially thank Dr. Megan Rose and Haruka Kurebayashi for contributing to this project.