Sitting Still: Painted Girl Portraits

Sitting Still is the first in a three-part exhibition series exploring representations of girls in fine art. Focusing on painted portraits of girls, it showcases an impressive array of portraits that reflect upon the personal stories, experiences, and history of this group of girls and young women. Sitting Still explores not only how the perception of girlhood has changed over the years, but also how depictions and representations of girls has shifted over time.

The exhibition includes more than 45 paintings, miniatures, prints, and watercolors from public and private collections around the world. It presents a clear and nuanced picture of girlhood in art from the 15th century through to the mid 20th century. Topics such as beauty, status, faith, power, authority, love, loss, and family provide a fascinating insight into the pictorial and thematic characteristics of girl portraits.

Artwork is arranged chronologically and divided into five sections reflecting their specific artistic time period. They are accompanied by relevant information on both the sitters and artists. Some of the images are famous and some are quite obscure. We hope you enjoy learning about the girls featured in Sitting Still.

Podcast: Dido Belle

Educational Guide

Our printable PDF guide is suitable for K-12 and college students. Curriculum links for USA and UK educational standards are included.

What is a portrait?

At its most basic level, a portrait is an image that represents a person or people. But there are many layers to this reality. Who had their portraits painted is a key question. Typically, it was important white men, usually the wealthy or powerful. Their portraits were made to demonstrate status as well as to memorialize it for posterity.

We must remember that most portrait paintings were made before photography was invented. So, while people could look in mirrors, they had no way of knowing what people they had not met looked like. Many portraits, especially of women and girls, were made so potential husbands could see them before they agreed to marry them. They were also made to commemorate a recent wedding or even an early death to not forget what the deceased person looked like.

Portraits from different time periods tell us different things, especially about how the sitters were thought of and what art conventions were at the time. All these things, as well as the expression, clothing, and background give us clues about the sitters’ lives. This is especially significant to learn about girls because they were mostly unnamed, and their stories have been lost or neglected. Consider these ideas as you view the exhibition.

The National Gallery of Scotland produced this excellent video explaining portraiture and how it can be hard to define.

Renaissance

Taking place between the 14th and 17th centuries, the Renaissance period saw a cultural movement that revived humanistic interest in classical (Greek and Roman) art, literature, and philosophy across Europe. Renaissance art was generally characterized by a realism that focused on human nature and its beauty. Girls in Europe were portrayed with either an exact likeness or as an ideal, with their beauty and status emphasized by the clothes they wore and poses they held. Their portraits were painted by artist family members or commissioned by wealthy aristocratic families to commemorate betrothals or marriages, or to be kept as mementos. These girls were always the focal subjects of their individual portraits, standing out against darker, plain backgrounds, a feature not normally observed in girl paintings from Asia at this time. In Asia, girls were also portrayed as true-to-life, but they were often painted as part of larger, complex compositions. During the Safavid dynasty in Iran, girls were illustrated in manuscripts and books, appearing in miniature paintings inspired by mystical and lyrical poems of the time. In China, girls were depicted in scenes from their daily life that highlighted their innocent and carefree nature.

Petrus Christus, Portrait of a Young Girl, 1470. Tempera and oil on an oak panel, 29 x 22.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany.

The girl’s identity in this portrait is not confirmed, so her age is unknown. The sitter is strongly believed to be a member of the English aristocratic Talbot family. She wears a blue gown laced with fur trimmings and a black chemise, with a thin and expensive gossamer ‘tissue’ draped around her shoulders. On her head sits a large, black velvet headdress with intricate gold embroidery; a variant of the truncate or beehive hennin which was fashionable in the Burgundian court. Her headdress is secured by a ribbon, and she is wearing a three-strand pearl necklace. She gazes at the viewer with an ambiguous expression. Her facial features are elongated, her eyebrows plucked, her hair drawn back to reveal her forehead and her shoulders are painted narrow: all a reflection of Gothic ideals of the time. The portrait’s background is a stylistic development in portraiture, as shadow and light were used to portray the girl close to the wall but not against it, establishing a three-dimensional setting.

Hans Memling, Tommaso di Folco Portinari (1428-1501); Maria Portinari (Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, born 1456), ca. 1470. Oil on wood, 42.2 x 32.1 cm (painted surface), 44.1 x 34 cm (overall). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913.

This portrait is striking due to the depth and detail involved in producing a highly realistic piece. Hans Memling was one of the most requested portrait painters of his time. Maria Maddalena Portinari is around 14 years old in this painting, shortly after her wedding to banker Tommaso Portinari. She represents late 15th century fashion with black and dark clothing, yet this was atypical in comparison to fashionable Italian costume at the time, which favored light floral gowns. Her hennin, the headpiece, was a vital indication of high-profile Burgundian women, emphasizing the physical attributes of portraiture that alluded to an individual’s social standing. Her pale skin stands out against the dark background.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474-1478. Oil on panel, 38.1 x 37 cm. The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

This portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci is one of the first known three-quarter-view portraits painted in Italian art. Her identity is confirmed by the emblematic juniper wreath on the painting’s reverse panel and juniper leaves that frame her face: both a wordplay on her name and symbolism of her chastity. The simplicity of her clothing and lack of extravagant adornment within the painting is surprising, especially considering her family’s aristocratic status. Leonardo da Vinci broke with prior conventions in Italian portraiture, painting Ginevra facing forward as she gazes at the viewer with an ambivalent expression. Perspective, as well as contrasting light and shadow, were used to create the impression that she has come to life. A contrast to the traditional profile portraits of Italian Renaissance girls of the time. As girls were normally kept within the walls of their homes, Ginevra also breaks with the typical as she is depicted in an outdoor setting.

Who was Ginevra?

Ginevra de’ Benci was the aristocratic daughter of a wealthy banker: a girl who was well-known at the time to be a poet and educated conversationalist in Florentine society. She is most commonly recognized today as the sitter of Leonardo da Vinci’s only painting located in America, of the same name. At the time of this painting’s creation, she was 16 years old and about to be wed to Luigi Niccolini, a 32-year-old widower.

Her identity is confirmed and supported by the emblematic juniper wreath on the painting’s reverse panels and the background’s juniper bush leaves that frame her face. Both a reference and clever wordplay on Ginevra’s name, as juniper translates to ginepro in Italian. The juniper leaves could also be interpreted as a reference to Ginevra’s chastity, which was considered by men in Renaissance society to be a girl’s greatest virtue: one that was valued and highly guarded, as girls of the time were expected to conduct themselves with modesty and dignity.

Taking a more naturalistic approach in his painting, Leonardo uses perspective and contrasting light and shadow to subtly model Ginevra’s face and appearance, making the girl seemingly come to life. He innovatively portrays her facing forward as she stares back at the viewer with an unreadable expression, breaking with established conventions of earlier Renaissance portraits that typically painted girls in detached profile views. Despite full-faced portraits (where the sitter looks forward) of women and girls already appearing in Northern Europe, profile view portraits of Italian women and girls were still the generally accepted norm in 1470s Italy. Therefore, Ginevra’s portrait, one of the first known three-quarter-view portraits painted in Italian art, was considered to be a technical development in Italian portraiture at the time. In addition, Leonardo also placed Ginevra outdoors, within an open setting as the young girl is surrounded by an array of natural elements like trees and a lake. This is another aspect of Ginevra’s portrait that was stylistically unique: in Italian girl portraiture girls were often depicted at home or indoors.

Furthermore, despite her high birth and family status, there is a notable lack of adornment, jewels, and luxury clothing on Ginevra in this portrait: a feature that would generally be included in portraits to display a family’s wealth and prestige. This is even more surprising considering art historians have interpreted this portrait to be a wedding portrait, commissioned to commemorate Ginevra’s betrothal and marriage to Luigi Niccolini. Female wedding portraits of the time often detailed brides in luxurious brocades, jewels and extravagant dresses received from their husbands during the counter-dowery exchanges between families, yet Ginevra wears none of these.

In Renaissance portraits aspects of the sitter’s personality and beliefs are illustrated within the paintings. As the piece of cloth was the only accessory Ginevra had chosen to wear for her portrait, it is evidently something very important to her and alludes to her long-standing religious affiliation with the Benedictine nunnery Le Murate, where the girl boarded and studied for years before her marriage. She would have been educated by the nuns in subjects such as reading, writing, arithmetic, and music, potentially even Latin. The convent provided a safe and free space for independent, educated young girls to be creative and intellectually stimulated away from the influence of male dominance in Renaissance society.

Ginevra’s relationship with Le Murate did not end entirely after her marriage as convent records have revealed that she was vested there as a nun at death. There was no record of her ever having any children. She left her entire estate to her brother, Giovanni Benci, when she died.

Considering the trends of the time, it is possible that the Benci family commissioned Leonardo to paint this portrait for themselves, as it was becoming more common for families to commission portraits of young Florentine girls as mementos. This was done to either preserve their memory when they get married and leave the household, or if they died young. Like other interpretations about the origins of Ginevra’s portrait, this interpretation has not been confirmed either.

At some point between the portrait’s completion and 1780, an estimated 6–8 inches of the painting’s lower panel believed to have been Ginevra’s arms and hands was damaged and removed. Based on a surviving drawing from Leonardo and comparisons to his other female portraits, it is suggested that her hands could have been painted similarly to another famous painting of his, the Mona Lisa (1503). Except, unlike the Mona Lisa, Ginevra was believed to have been holding a small sprig, a flower frequently used in Renaissance portraits to represent virtue and devotion, perhaps a reference to the girl’s religious devotion to her beliefs. Despite the numerous theories and questions that surround her painting, Ginevra’s portrait is a significant piece of art in Italian portraiture. Breaking with traditional stylistic conventions it paved the way for girls to be painted in the same manner as Renaissance men.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Portrait of Princess Sybille of Cleves, Wife of Johann Friedrich the Magnanimous of Saxony, 1526. Oil on panel, 53. 3 x 38.1 cm. Private collection.

This portrait depicts 14-year-old Princess Sybille of Cleves, who was newly engaged to Johann Friedrich, the future Elector of Saxony. It is highly symbolic of her high social status and her recent betrothal. Sybille wears a jeweled and feathered wreath that was typically associated with virginity and was presented to the groom as an offering of a virtue. This is highly relevant to the context of this period where virtue was a key element regarding a girl’s social position. Furthermore, she has a youthful and beautiful appearance, with her hair hanging loose. Portraits such as these were often a symbol of an engagement and within this painting, Sybille wears a pendant that represents the union of the two families as well as the gold fabric woven into her dress which alludes to the House of Saxony.

Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci), Portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici and Giulia de’ Medici, ca. 1539. Oil on panel, 88 x 71.3 cm (painted surface), 113.03 x 92.08 cm (framed). The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902.

This image depicts the widowed wife of military leader Giovanni delle Bande Nere de’ Medici, Maria Salviati. She is shown with a young Medici relative, Giulia who was raised in Maria’s household. Giulia was the daughter of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici. A sense of a relationship is formed between the two where Giulia grasps onto Maria’s long fingers, which is symbolic of her aristocratic position. However, unlike portraiture at the time, both figures appear to blend into the background, imposing a sense of depth and sadness into the image. Alessandro was the son of a Medici cardinal, and it was believed his mother was an African servant. This portrait is possibly one of the first formal portraits of a girl of African descent in European art. Giulia has some characteristic features of this parentage, however Giulia and Maria both have pale skin. While this was fashionable at the time, some use it to call into question Giulia’s ancestry.

Sofonisba Anguissola, The Artist’s Sister in the Garb of a Nun, 1551. Oil on canvas, 68.5 x 53.3 cm. Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton, UK. Purchased in 1936 through the Chipperfield Bequest Fund.

This portrait is by Sofonisba Anguissola, and was most likely painted to commemorate her sister, Elena Anguissola, taking her vow to become a Dominican nun. In this three-quarter-length portrait, Elena is portrayed in her white habit against a dark green background. She holds a red leather-bound prayer book with gold decorations as matching red ribbons fall from the pages. From the way Elena’s eyes gaze back at the viewer, to the fine details of her facial expression and garments, Anguissola has delicately captured her sister’s persona within her painting. As a female artist, she was prohibited from joining artist guilds and painting the complex multi-figure compositions necessary for historical or religious paintings because she had been forbidden from studying anatomy and life drawings. Instead, she was encouraged to sketch and draw herself and family members since portraiture was considered to be the most appropriate form of art for ladies.

Alonso Sánchez Coello, Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, 1579. Oil on canvas, 116 x 102 cm. Royal Collection, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

This painting depicts Isabel Clara Eugenia, the eldest daughter of Felipe II. Isabel was one of the most important women in this family, with this piece as evidence of her high social standing. Her right hand on an armchair shows her established position in court and a handkerchief in her left hand is traditional to female portraits. Her fashion is symbolic of Spanish fashion in the 1580s: she wears a feathered headdress and an array of jewelry with stones that further display her social status. In keeping with portraiture of the time, Isabel stands with a distant gesture in the frame of the portrait, her illuminated presence reinstates a sense of authority over the viewer.

Lavinia Fontana, Portrait of Antonietta González, 1595. Oil on canvas, 57 x 46 cm. Musée du Château, Blois, France.

This portrait is of Antonietta, one of the daughters of Petrus Gonsalvus (Pedro González). She and her family suffered from hypertrichosis disease, which caused abnormal hair growth over the body. She is less than ten years old in this portrait and the artist displays a sense of youth and innocence in the painting. Set against a dark background, Antonietta is brought closer to the viewer and is shown as doll-like and dainty, characteristic of her young age. Lavinia Fontana, a female artist, conveyed a child-like sense in this painting. Despite the curiosity of many contemporaries, this young girl was a symbol of rarity. Her attire seems to signify her acceptance by society.

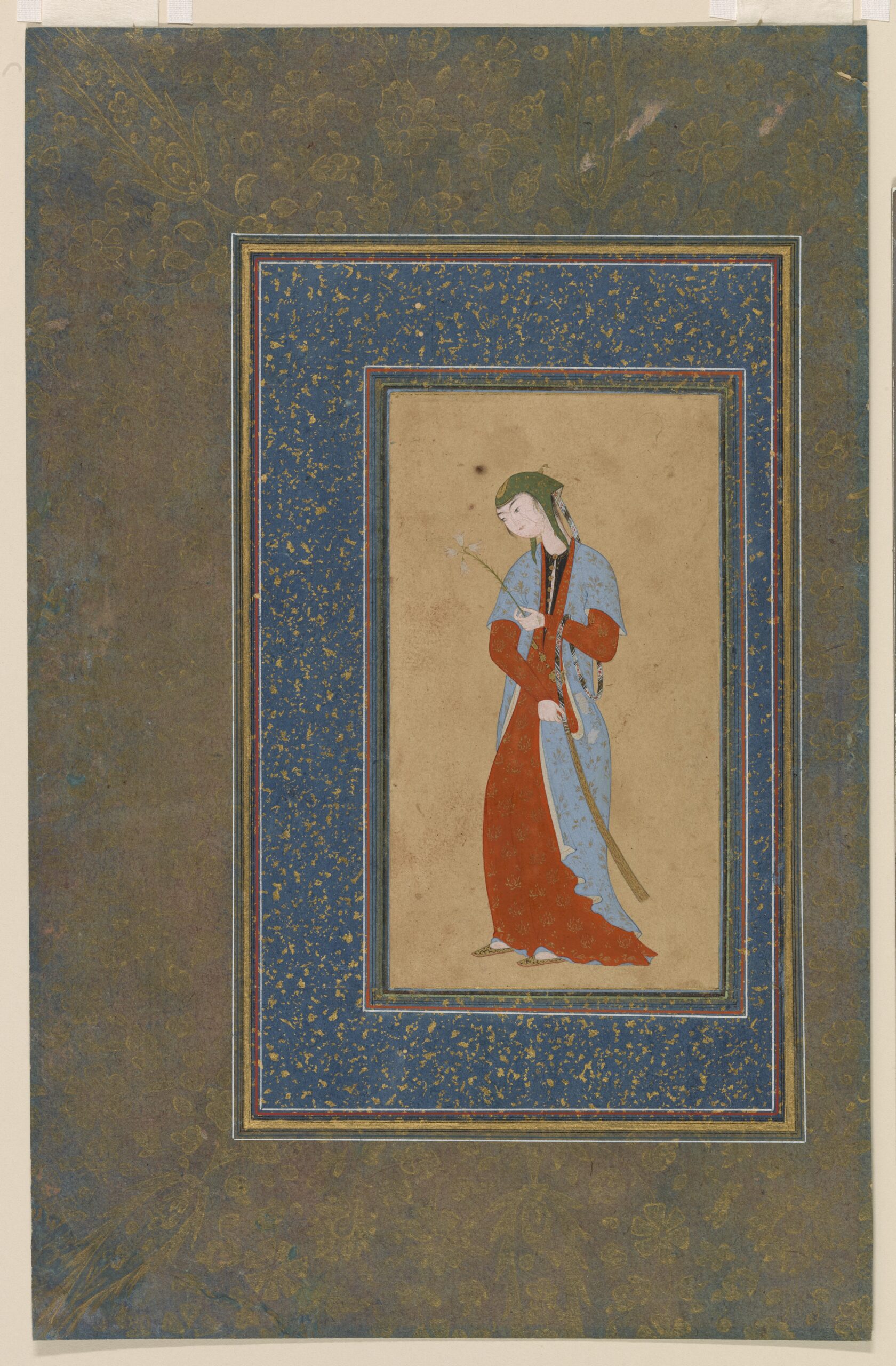

Unknown, Young woman with a spray of lilies, Safavid period, 16th century. Opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 14.3 x 7.9 cm. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA. Purchase – Charles Lang Freer Endowment.

This Persian miniature painting depicts a young woman of indeterminate age dressed in courtly garments, holding a spray of lilies as she daydreams, which was a popular painting subject at the time. She appears reserved and distant; a reflection of how unapproachable women were portrayed in mythical and lyrical poems of the period. Her identity is unknown, and it is possible that she did not exist at all. As most manuscript paintings were created by a workshop (a group of male artists); it is impossible to attribute this painting to an individual. She is depicted with a round, white moon face and rose bud lips. Her hair is pulled back by a green and yellow veil and fastened by a decorative ribbon of silk that she holds. Dressed in loose layered clothing, brocaded by golden floral motifs, she is framed by a series of dark blue and gold borders. Gold floral motifs and arabesques (two common decorative motifs in Islamic art) appear to sprout out from behind those frames.

Baroque

The Baroque art period was roughly between 1600 and 1750. It incorporated some Renaissance stylistic characteristics but was typically more extravagant and characterized by a sense of grandeur and drama. The thematic use of chiaroscuro (an oil painting technique that uses strong contrasts between light and dark) and tenebrism (a painting style that uses pronounced light contrasts for dramatic impact) to create an intense contrast between partially lit figures and dark atmospheric backgrounds were especially prevalent in portraits of European Baroque girls.

Like Renaissance girls, some girls posed with objects in backgrounds that alluded to their high status and birth, while others were depicted within scenes of their daily home lives. Baroque girls were painted in a less idealized manner than Renaissance girls and were more expressive in their movements and facial expressions. Despite the spread of Baroque art to European colonies such as India, the style did not influence portraits of girls outside of Europe. Portraits of Indian and Iranian girls were still painted in poses and styles that adhered to society’s standard of beauty. In Japan, girls were similarly painted within scenes of their everyday lives but in the ukiyo-e style, unique to Japanese art. Overall, portraits of Baroque girls continued to be either painted by family member artists or commissioned, but as we see a new group of middle-class art patrons emerge, there is a noticeable shift towards using girl studio models in paintings.

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Clara Serena Rubens, c. 1616. Oil on canvas, mounted on panel, 37 x 27 cm. The Liechtenstein Museum: The Princely Collections, Vienna, Austria.

This portrait of Clara Serena Rubens was left unfinished by Rubens and trimmed down on all sides before 1656. It depicts Ruben’s lively five-year-old daughter from his first marriage to Isabella Brant. This painting reveals the methods that the artist used in developing his portraits. Clara’s costume is hastily painted, and the white collar is deliberately used to frame her rosy face.

This painting is a live study, with the facial features captured with rapid strokes. Clara’s individuality is rendered realistically with her irregularly set eyes and the slight twist of her mouth. Her hair is swept back with a few strokes and her eyes gaze straight out at the viewer. This direct and immediate contact with the viewer is not typical of contemporary portrait painting and is a technique Rubens used specifically for his intimate portraits of his family, showing the close relationship between the artist and his daughter.

Attributed to Lalchand, Agra or Burhanpur, India, Princess Jahanara aged 18, 1632. The British Library, Add Or 3129, f. 13v. London, UK.

This portrait of Princess Jahanara is part of an album compiled by her brother, Prince Dara Shikoh. Many of the paintings in the album depict figures from the imperial court and offer an intriguing glimpse of court life during Mughal rule. Jahanara Begum was an imperial princess who took over the responsibilities of the Empress at the age of 17, when her mother died. She was also a follower of Sufism, a writer, and a patron of the arts. She regained her position even after one of her brothers overthrew her father and his heir apparent, and had her own tomb constructed of white marble.

In this portrait, she is pictured eating fruit, perhaps a mango. Fruit often appears in Mughal portraiture and is thought to have been viewed as evidence of status and a tool of diplomacy. The mango had particular significance, tying the Mughal rulers to the territory of India.

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Elizabeth and Philadelphia Wharton, 1640. Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

This is a portrait of Philadelphia and Elizabeth Wharton, the daughters of Philip, 4th Lord Wharton. The girls are shown posing statically against a draped and imaginary backdrop. They are wearing elaborate upper-class adult dresses tailored for children. The eldest girl is dressed in a dazzling white gown with a shawl draped over her shoulder. The youngest girl is wearing a finely woven dress with a white collar or a white shift underneath. Their rounded cheeks are surmounted by a head of dark red curls. The girl on the right gently holds her sister by the shoulder, frozen in the pose in which she has been asked to stand in by the artist. Their faces are exquisitely modelled and full of expression: the girl on the left gazes out at the viewer with confidence and ease; a little dog jumps up to catch her attention by scratching at her dress with one paw.

Rembrandt, Girl in a Picture Frame, 1641. Oil on panel, 105.5 x 76 cm. The Royal Castle Museum, Warsaw, Poland.

This is a beguiling depiction of an elegantly dressed unknown young Jewish girl. Rembrandt often portrayed figures dressed in historic costumes, as seen here. The sitter wears a dark red, fur-lined dress, gold necklaces, a wide belt and a grand black beret that shades her face. Her long, red hair is worn loose. According to Jewish tradition, a bride wore her hair loose when signing the marital contract with her fiancé.

Girl in a Picture Frame is also known as The Jewish Bride. By placing her delicate fingers on a black picture frame and leaning out, she appears to be entering the realm of the viewer. She is looking at her surroundings with a direct and contemplative gaze. Her raised eyebrow suggests a hint of surprise. The sense of movement is strengthened by the pearl earring which hangs away from her head. The overall effect is uncanny, playing upon the division between reality and the illusion of painting.

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656. Oil on canvas, 320.5 x 281.5 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

One of Velázquez’s masterpieces, this portrait shows the five-year-old Infanta Margarita, daughter of Philip IV of Spain and Mariana of Austria. She is surrounded by female attendants alongside two court dwarfs. Velázquez depicts himself in the act of painting, looking out at the viewer. The figures reflected in the mirror are thought to be the King and Queen. The composition is designed to draw our intention to the Infanta. She stands out in the center, with her dress, white blonde hair and pale skin seeming to reflect the light. Her paleness may be partly explained by the small red jug being offered to her by an attendant. The jug has been identified as a búcaro, made from a Mexican red clay, which girls in 17th century Spain slowly ate for its lightening effect on the skin. It was considered desirable due to racist and classist ideals.

Mary Beale, Portrait of a Young Girl, c.1681. Oil paint on canvas, support: 535 x 460 mm, frame: 710 x 640 mm. Tate Britain, London, UK.

This profile portrait is an engagingly informal oil sketch of an unidentified girl. The artist, Mary Beale, was one of the first professional female painters in England. She often used members of her family and studio assistants as her models, so the sitter shown here could possibly be Kate Trioche, a studio assistant, or Alice Woodforde, Beale’s godchild. A great deal is known about Beale’s work because her husband, Charles, who primed canvases, kept a detailed account of her studies and experiments in an annotated almanac. This portrait appears to have been ‘painted up at once’, meaning in a single session. This quicker process can result in colors appearing muddy and opaque, as in some parts of this portrait. Nevertheless, the resulting sense of informality adds to the relaxed depiction of the girl.

Jan van der Vaardt & Willem Wissing, Queen Anne, when Princess of Denmark, 1665-1714, about 1685. Oil on canvas, 199.40 x 128.30 cm. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

This portrait depicts Princess Anne, the second daughter of James II of England in the same year that he succeeded to the throne. She is shown aged about 18, in robes of state, with a palace in the background. The red and pink flowers beside her match the richness of her red dress and emphasize her beauty as a young princess of marrying age. Her pose is relaxed but, as she stands within a full composition, she appears tall and stately.

Anne was born in London in 1665, a year before the Great Fire. She had spent her early years in France with her grandmother and aunt until her mother’s death in 1671. In 1683, she married the protestant Prince George of Denmark. However, their marriage was marred by Anne’s miscarriages, stillbirths, and the death of their children: five children were born alive, and none reached adulthood. Meanwhile, Anne’s father was overthrown and, after the deaths of her sister and brother-in-law, Anne herself became queen in 1702.

Jean-Marc Nattier, Portrait of the Marquise d’Antin, 1738. Oil on canvas, 118 x 97 cm. Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, France.

The girl in this painting is Mathilde de Canisy, the Marquise of Antin, who was 14 years old at the time. Mathilde wears a fitted bodice over a white silk dress that accentuates her neck and bare shoulders. Draped across her body to optimum effect is a lively floral sash. Her hair has been coiled around her head and adorned with flowers. The sitter is gracefully seated at the foot of an oak tree whilst gazing into the viewers eyes. Nattier painted her cheeks rose with blush, which was a popular cosmetic style during the Rococo period. Her bright blush contrasts with her ivory skin, powdered hair, and soft features. Mathilde is set against a landscape background. The landscape has been rendered with precision and the sky is reflected in the depths of the river.

Muhammad Sadiq, Painting of a Young Beauty, 1740s-50s. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on cloth, page: 31.8 x 20.3 cm, painting: 14 x 7.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Purchase, Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2011.

The Persian girl or young woman in this painting typifies the representation of youthful feminine beauty of this time. With her round face, almond-shaped eyes and central parted hair style, she appears at once a particular and idealized girl. Sadiq is best known for his oil paintings, however, this watercolor effectively displays his aptitude at capturing the mood of his sitter via her eyes and direct gaze. She is looking intently away from the viewer, not coquettishly, but with purpose, appearing to be watching something that interests her. Within this painted frame with brightly colored floral motifs her face is set amongst the beauty of nature.

Nishikawa Sukenobu, Girl sitting on her bed near an outer doorway and grinding ink, Edo period, 17th-18th century. Hanging scroll (mounted on panel), color, black and gold on silk, 35.2 x 65.9 cm. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA. Gift of Charles Lang Freer.

In this painting Sukenobu reveals his skill and his devotion to everyday themes. A girl is seated on her bed, holding a suzuribako (inkstone case) and grinding ink to write a letter. Bed quilts are piled on her bed, and behind the girl is a folding screen. The girl wears a blue robe patterned with a diaper (white diamond) motif. The girl looks out across a veranda into a garden. The veranda cuts diagonally across the composition to give the painting a sense of depth.

This print is typical of the ukiyo-e style, which means ‘pictures of the floating world’, referring to the licensed brothel and theatre districts in Japanese cities where the tradition originated. This girl, however, is neither theatrical nor attired as a courtesan, but simply a resident, performing an everyday activity. Girls were often maids or apprentices to old women in the floating world. The ukiyo-e style was targeted at all social classes and often focused on ordinary subjects.

Age of Empires

From 1750 to 1830, much of the world was governed by large empires, including the British, French, Dutch, Japanese, and Mughal. Art from this period reflects the cultural interactions created by this political landscape, including simplification of the cultures of oppressed people, as well as adoption of their clothing, symbolism, and techniques (what we now call cultural appropriation). Girls were a common subject for paintings in Europe, as the wealthy continued to commission portraits of their families, and women and girls were valued for their beauty. Ideas of childhood innocence and playfulness were also idolized.

While portraiture for the wealthy classes was less common across Asia, girls were featured in paintings because of their roles as actresses, dancers, and courtesans, or as representatives of their cultures in imperial narratives. European art of this period retained elements of Baroque painting, often with a simpler composition, including plain backgrounds, which contrasted with the fine dress often used to show girls’ status. In Japanese art, the ukiyo-e style, which translates as ‘pictures of the floating world,’ was widely popularized. It depicted young courtesans and familiar actresses, alongside images of girls playing traditional games and undertaking everyday tasks.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Painter’s Daughters chasing a Butterfly, c.1756. Oil on canvas, 113.5 x 105 cm. The National Gallery of Art, London, UK. Henry Vaughan Bequest, 1900.

This is a portrait of Thomas Gainsborough’s two young daughters, Mary and Margaret, in a dark garden setting. Their exact ages in the portrait are uncertain, as we don’t have records of their dates of birth. They are holding hands and the younger girl, Margaret, is reaching out towards a Cabbage White butterfly. Both girls wear fine ankle-length dresses with overskirts and have their hair up in elaborate styles, presenting them as refined and wealthy. Their mother was Margaret Gainsborough (née Burr).

Their father was one of Britain’s most renowned painters and was sought-after for his portraits of the rich and famous. The painting is in a similar style to Gainsborough’s famous portraits of wealthy adults, with soft brush strokes, seemingly natural poses, and a detailed landscape in the background. This portrait, however, highlights the girls’ relationship and their innocent play, rather than a sitter’s wealth, power or attractiveness which were often emphasized in Gainsborough’s work.

Angelica Kauffman, Henrietta Laura Pulteney (1766-1808), c.1777. Oil on canvas, 74.3 x 61.8 cm. The Holburne Museum, Bath, UK.

Kauffman’s portrait depicts Henrietta Laura Pulteney picking flowers in a wood, dressed in white. Henrietta was the only child of Frances Pulteney and Sir William Johnstone, who took the name Pulteney for himself and (Henrietta) Laura after inheriting his wife’s family’s estate. William Johnstone was a slave owner, landowner, politician, and supposedly the wealthiest man in Britain at the time.

This portrait was painted when Laura was eleven. Laura was known to love dancing, so the posture may reflect her personality, while the fine details of her outfit show off her wealth. Angelica Kauffman was a Neoclassical painter and founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. She was a popular and respected painter of both history paintings and portraits, so commissioning a portrait from her showed the status of the Pulteney family.

David Martin, Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, c.1778. Oil on canvas. Scone Palace, Perthshire, Scotland. Courtesy of the Earl of Mansfield and Scone Palace.

This portrait of two cousins is significant in European social history, as it depicts a Black girl of high social status in 18th century England, painted alongside her white cousin. Dido Elizabeth Belle was the daughter of a British naval Captain, Sir John Lindsay, and an enslaved African woman, Maria Belle, born in the British West Indies. Her father brought her to England in 1765, where she lived in the aristocratic Kenwood House along with Lady Elizabeth Murray, the other girl featured in the portrait.

Dido’s exact position in the household is still unclear and this portrait depicts a complicated reality. She stands slightly behind her seated cousin, wearing an exoticized outfit, including a bushel of fruit and a feathered turban. However, she wears expensive clothes and jewelry and the affection between her and her cousin is clearly shown.

Francisco de Goya, María Teresa de Borbón y Vallabriga, later Condesa de Chinchón, 1783. Oil on canvas, 134.5 x 117.5 cm. The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

María Teresa was the daughter of the Infante Don Luis of Spain, who had previously claimed the throne, but lost the succession to his brother, and was sent to live away from court at the palace in Velada. Goya’s portrait of María Teresa is from 1783, when she was two years old. Goya was friendly with the Infante’s family and painted several portraits while staying with them in 1783 and 1784.

The background of this painting shows the mountainous surroundings of Velada in rich detail. In the earlier period of his career, Goya’s commissions from the royal family and other aristocrats often included portraits like this, which served to display the families’ status. He shows María Teresa dressed as a lady, wearing a lace veil, blue bodice, shoes, and a traditional black skirt (basquiña), with a small Maltese dog at her feet. Her costume contrasts with her small stature but may have been selected to emphasize her connections to the high fashions of the Spanish court, despite her father’s position.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Julie Le Brun (1780-1819) Looking in a Mirror, c. 1787. Oil on canvas, 73 x 59.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Bequest of

Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2019.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun often painted portraits of her daughter, Julie. In this image Julie, aged about seven, stands in profile, holding a mirror to her side, and her reflection appears to look back at the viewer. Mirrors in paintings are often associated with either vanity or self-knowledge. Julie’s young age and simple, smart clothing make us more inclined to see the latter. As Julie’s reflection gazes out at the viewer, perhaps we may feel that she knows us too.

Julie grew up in Paris, where her mother was under the patronage of Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France at the time. Just two years after this portrait was painted, Julie and her mother fled the French Revolution. Julie became an artist herself, beginning at a young age and working with pastels.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Penelope Boothby, 1788. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Reynold’s portrait of Penelope Boothby is one of the most famous English child portraits, often known as The Mob Cap. In this portrait, Penelope is depicted at three years old. She was the only child of Sir Brooke Boothby, a poet, linguist, and translator, well known in English literary circles. Her frilly lace mob cap, rosy cheeks and exaggerated cupid’s bow lips portray an ideal of upper-class Victorian girlhood, representing innocence, beauty, and playfulness.

Reynolds was one of the most popular portrait painters of the time and his methods particularly suited young children, minimizing the sitting time. Penelope became ill and died at the age of five. Her father had a remarkable tomb constructed, with a life-size sculpture by Thomas Banks. He published a book of poetry, Sorrows Sacred to the Memory of Penelope and Penelope’s image inspired further works by Henry Fuseli, John Everett Millais, and Lewis Carroll.

Torii Kiyonaga, Chinese Girls Playing Cards, No.8 from the series The Children Say “This Is Japan!” and Play the Games That They See in the Picturebooks, Edo period, c.1791. Woodblock print (nishiki-e), ink and color on paper, 24.6 x 18.6 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA. Denman Waldo Ross Collection.

Torii Kiyonaga was an important ukiyo-e painter. The ukiyo-e tradition used woodblock printing to reproduce images, making it more affordable to every social class. This painting is the eighth in a series entitled The Children Say “This Is Japan!” and Play the Games That They See in the Picturebooks. The series also includes images of activities such as flying kites and copying paintings. The girls appear in natural poses as they play. They wear kimonos, without makeup and with their hair tied up in a simpler style than the popular nihongami often worn by adult women in ukiyo-e paintings. Card games like this were very popular in China and provided entertainment for adults, boys and girls.

George Morland, Indian girl, 1793. Oil on canvas mounted on panel, 21 x 22.9 cm. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

From the 1750s, the British East India Company gained increasing control of Indian territories, establishing what was called the ‘Company rule.’ British campaigns to improve the treatment of native people across its empire often failed to acknowledge the agency of those people. In this painting, an Indian girl is portrayed as a vulnerable figure; her gaze is fearful, her hair and clothing disarranged, and she sits on the ground looking upwards to an unseen figure. As Morland did not travel to India, this portrait is likely imagined. The painting style employs a naturalistic pose, foliage background, and delicate brushstrokes for the hair, as in Baroque portraiture of the English aristocracy. This style is strikingly different both from artwork created by Indian artists and from ‘Company paintings:’ works by British artists in India under Company rule, often including some elements of local Indian styles.

Unknown, Portrait of a Young Woman, late 18th century. Pastel, 40.6 x 32.4 cm. Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, USA.

Little is known about the circumstances of this portrait. The sitter has previously been misidentified as two other women of color, the poet Phillis Wheatley and the heiress Dido Elizabeth Belle, though neither possibility is likely. The sitter’s headscarf, called a tignon, is not a style that was fashionable in Europe, but was worn in the Caribbean and parts of the colonized American mainland. After laws were introduced forcing women of color to cover their hair, many turned their tignons into marks of distinction, using elaborate knots and expensive materials, like this fine white silk.

The portrait has previously been attributed to Jean-Étienne Liotard, a Swiss pastel portrait artist. The soft background and textured skin is in keeping, but the abstracted representation of the dress is more unusual for Liotard. An imprinted watermark of a Dutch company in the paper suggests the true artist may have been from, or working in, the Netherlands.

The 19th Century

The social, political, and cultural changes that took place around the world during the 19th century are difficult to condense into any number of words. With the continued growth of some Empires, especially the British and French, and the technological advancements of the Industrial Revolution, impacts on the people and the planet are immeasurable. The fine arts experienced the proliferation of ‘movements,’ culminating in an art explosion across Europe and the Americas at the end of the century, creating an ‘art world’ and standardizing ideas about artists and their work that still lingers today.

Girls became more of a focus of society, in terms of their innocence and molding them into ‘perfect’ women. As subjects of art, they became metaphors, archetypes, and allegories, while still consistently used as portrait sitters. However, they remain anonymous or de-identified, valued for their beauty or social standing and not their subjectivity. Girls were very popular, especially in works of the Impressionist painters, who used them as a bridge to nature for their perceived simplicity as well as natural bodies. The male gaze and imposed sexuality become more overt than ever before during this time period, exacerbated by the advent of the photograph.

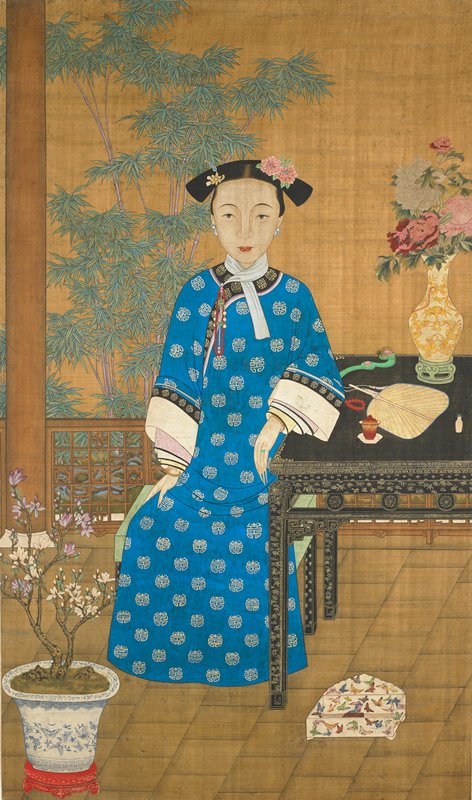

Unknown artist, China, Birthday Portrait of a Young Manchu Lady, c. 1800-1850. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk, 114.78 x 67.63 cm. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton.

In this portrait, an unidentified aristocratic young Manchu girl sits on a garden terrace for a birthday portrait by an anonymous artist. Her attire and all the objects in the painting are a wish for her long life. Her blue robe, for example, is decorated with the character of shòu for longevity while the flowerpot and box at her feet feature butterflies, a Chinese pun for ‘age 70.’ Magnolias and peonies are often painted together in Chinese art representing female beauty, as they do in this portrait. Separately, the magnolia represents purity while the peony symbolizes honor and prosperity. The girl is surrounded by expensive objects that point to her high social status like a fan, a ruyi (wish-granting) scepter, a porcelain flower vase, and a snuff bottle at her elbow.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Princess Gouramma (1841-1864), 1852. Oil on canvas, 153.2 x 91.8 cm. The Royal Collection Trust, Durbar Corridor, Osborne House, Isle of Wight, UK.

In 1852, Queen Victoria commissioned Franz Xaver Winterhalter to paint a portrait of the newly baptized Princess Victoria Gouramma. Adept in both Rococo and Neoclassical styles, Winterhalter depicts Gouramma standing near columns wearing beautiful, intricate Indian garb while leaning against a table featuring Indian artwork. The Bible in her hand highlights Gouramma’s conversion to Christianity. The use of Indian and Christian elements together was intentional and provide a visual summation of Gouramma’s life.

Gouramma was the daughter of Chikka Vira Rajendra, Coorg’s last ruler prior to British colonization, and she was used as a tool to both fight and further incursions. The lightest of her sisters, Gouramma was a key component in her father’s successful plot to wield the British colonial mindset to escape exile and gain passage to England, while the British monarchy attempted to use Gouramma to proselytize in India to further colonize the subcontinent. Gouramma rebelled, however, becoming the center of at least two scandals with young men. She married a British military man at nineteen and died at 23 after contracting tuberculosis for the second time.

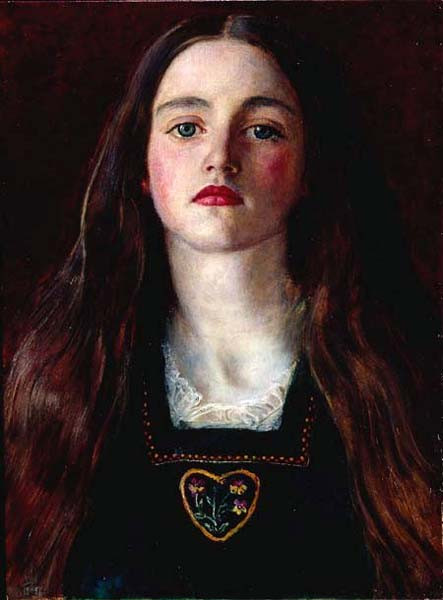

John Everett Millais, Portrait of a Girl (Sophie Gray), 1857. Oil on mounted paper laid over panel, 30 x 23 cm. Private collection.

Sophia Margaret “Sophie” Gray was fourteen years old when she sat for her second portrait by artist John Everett Millais, her brother-in-law, in his London studio. A trained academic painter, Millais’s departure from Pre-Raphaelite composition and attention to detail and working-class subject matter proved controversial. John Millais became one of the foremost portrait artists of Victorian children.

Sophie Gray continued to sit as a model for Millais’s paintings over the years and was a subject of his work more often than Effie, her sister and Millais’s wife. Suffering from mental illness and an eating disorder by the age of 25, Sophie’s health declined. She died at only 38 years old with Millais painting her final portrait two years prior.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No.1: The White Girl, 1862. Oil on canvas, 213 x 107.9 cm. The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Joanna Hiffernan wears a white house dress, standing before a white curtain on a bearskin rug, grasping a white lily in her hand. Her red hair is loose, and she gazes directly at the viewer. Joanna was nineteen years old when James McNeill Whistler, her lover of two years, painted her portrait in the winter of 1861-1862. Attempting to establish his career as an artist, Whistler worked on Joanna’s portrait daily and submitted it to the 1862 juried exhibit at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. The 19th century viewers were uncomfortable with the Pre-Raphaelite portrait and Symphony in White was rejected many times before becoming one of the most popular works in an 1863 protest exhibition in Paris, then one of Whistler’s most famous paintings.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girl with a Jump Rope (Portrait of Delphine Legrand), 1876. Oil on canvas, 107.3 x 71 cm. The Barnes Foundation, Merion and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Courtesy of the Barnes Foundation, Merion and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Early in his career, Pierre-Auguste Renoir supported himself by painting portraits commissioned by the Paris elite. This is a portrait of five-year-old Delphine Legrand, daughter of Renoir’s friend Alphonse Legrand. He was an important figure who helped mount the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876. The conspicuous moving brush works in Delphine’s blue dress epitomize the impressionist technique while the saturated colors are specific to Renoir’s style. In her hands, Delphine holds a jump rope. Considering the fullness of the skirts of her dress, it was probably a prop and unlikely that she would have been playing at this. Girls at this time were able to go outside and not be confined to the home, as represented in many Impressionist works. However, their dress and the idealized way that middle-class society fetishized girls as little dolls limited their play, and they would not have been free to express themselves in many physical ways.

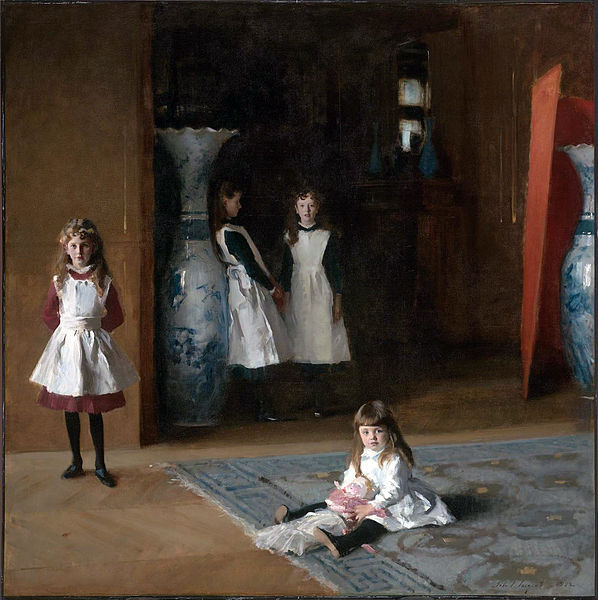

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882. Oil on canvas, 221.93 x 222.57 cm. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit.

Julia (age 4), Mary Louisa (8), Jane (12), and Florence (14) posed for a portrait in the autumn of 1882. Their father’s friend, John Singer Sargent, arranged them oddly in the foyer of their elegant and shadowy Paris apartment and painted an unusual portrait. Sargent presented each girl individually but obscured Jane and Florence’s faces, a contradictory practice for portraiture. The pinafores and upward glances at the viewer are thought to capture the sisters at play despite the lack of interaction among them.

The tall Japanese vases disguise the girls’ small size. Sargent sampled various approaches to portraiture from the past and present in his early works. The dark interior, subdued palette, and confrontational look echo Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, while the odd arrangement of the subjects as family members with little interaction was likely inspired by Sargent’s French contemporary Edgar Degas.

Kuroda Seiki, Maiko Girl, 1893. Oil on canvas, 80.4 x 65.3 cm. Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan.

A maiko is a geisha in training: between 17 and 20 years old they would sing, dance, and perform with traditional Japanese instruments during parties and other special events. When Kuroda Seiki returned to Kyoto, Japan in 1893 after nine years of studying in France, he saw the maiko girls with new, Western eyes. He imagined the girls as delicate and bird-like and painted a scene to match. The maiko girl is perched on a bench wearing a vibrant kimono, speaking with an older woman whose kimono pales in comparison.

Seiki is noted as one of the leaders of the Yōga (or Western style) movement in Japan. The Yōga paintings were impressionistic, using vibrant colors and lighting effects, a step away from the traditional Barbizon School. However, Seiki’s portrait of a girl, a maiko girl specifically, is solidly within the Japanese bijin-ga tradition that often focuses on maiko girls and geishas.

Cecilia Beaux, Ernesta (Child with Nurse), 1894. Oil on canvas, 128.3 x 96.8 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Maria DeWitt Jesup Fund, 1965.

Aimee Ernesta Drinker, the artist’s two-year-old niece and favorite subject, holds her nurse Mattie’s hand as they walk across a wooden floor, “…We see not a rambunctious two-year-old, but a self-possessed queen calmly surveying the kingdom passing before her,” as Mattie’s hand provides security and comfort. The composition and brushwork reflect Cecilia Beaux’s respect for artists Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas.

In a departure from the works of her contemporary, Mary Cassatt, Beaux painted her subjects as small adults. She commonly centered the child in her paintings, hence Mattie’s cropped figure. Beaux’s style for strong, likeness-driven portraits was often compared to John Singer Sargent’s works. Ernesta grew up to become an artist, traveler, and writer who often commented on the social issues of the day, and Beaux was honored by Eleanor Roosevelt as “the American woman who had made the greatest contribution to the culture of the world”.

Mary Cassatt, Portrait of a Young Girl, 1899. Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 61.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. From the Collection of James Stillman, Gift of Dr. Ernest G. Stillman, 1922.

An unidentified girl wearing a hat and a pink dress with puffy sleeves overlaid with black lace sits high on a hillside, a blade of grass extending from her fingers to her lips as she looks out across the green landscape and beyond. Mary Cassatt was a feminist Impressionist painter whose subjects were primarily women and girls, thus offering a new look on everyday life from a woman’s perspective. As she did with the girl in this portrait, Cassatt painted her subjects as complete and independent instead of secondary figures in relation to men. The flat background points to the Japanese influence on Cassatt’s art while the subject, setting, and visible brushstrokes present Cassatt as an Impressionist.

20th Century

The 20th century saw the development of numerous modernist art movements in the West. Artistic perspectives changed as artists experimented and approached new ways to represent reality. Girls were painted in a more emotionally expressive manner where subjectivity was preferred over realistic depictions. Portraits of American and European girls were colorful and painted in the stylistic trends of the time, with some being bolder in coloration than others. Their subjects varied as some were girls who the artists had encountered on their travels, while others were girls who had come to their studios to model. Some female artists even painted their own self-portraits.

In other parts of the world, various girl portraits were influenced by these Western styles. In South Africa, art movements like Expressionism (an artistic style that aims to represent subjective emotions) impacted how girls were portrayed. In Asia, artists familiar with Western painting styles painted girls similarly to their European counterparts, in styles more in line with 19th century Impressionism (a painting style characterized by small, visible brushstrokes) and Post-Impressionism. Despite the impact of the modernist art movements in Asia, Japanese and Korean girls were still painted in traditional art styles.

Simon Maris, Isabella, c. 1906. Oil on canvas, 41 x 29 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. A. van Wezel Bequest, Amsterdam.

This is a portrait of Isabella at 12 years old. She is sitting in an elegant chair decorated with rams’ heads on the armrests. Her attire is formal, from her headgear with flowers and a long bow that goes down to her lap, to her intricate blue dress. In her hand she has a delicate fan with blue dashes which match her dress. To Isabella’s right, there is a decorative mirror reflecting her back, although the hat covers the back of Isabella’s head, we can still see the black curls of her hair. Her stance seems demure, but her pose gives her a classic and aristocratic look. Previously, the identity of this sitter was unknown, and the painting was simply titled, The Negress or East Indian Type. Fortunately, research into the artist’s archives revealed her actual name. While we don’t know much else about her, saying her name is a start to recover girls’ voices in art history.

Élisabeth Chaplin, Self-portrait, 1908. Oil on canvas. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Élisabeth Chaplin was a French painter, who is known for her landscapes and portraits. She came from a family of artists. The family moved to Italy where Élisabeth painted untrained, but later she was mentored by Paul-Albert Besnard. She worked in Italy and France. This self-portrait shows Élisabeth as if caught midway through a stroll in the countryside during a stormy day, as told by the grey sky in the background and the fact that she is holding quite a large green umbrella.

Élisabeth is very close to the viewer and is turning as if she has been called. There is a neutral expression on her face. Her hair is down, and she is wearing a black hat with several dashes of color which resemble flowers. Élisabeth is dressed in a coat appropriate for what looks like autumn. She uses quite a dark color palette, with greys, dark greens, and browns, although the above-mentioned hat and flowers bring some light contrasts.

Mizuno Toshikata, Girl Playing with A Butterfly, late Meiji era. Color woodblock; ink and metallic pigment on card stock, 13.8 x 8.8 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA. Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards.

Although from different countries, this print by Mizuno Toshikata reminds us of the silk painting, Miindo (A Beauty) by Kim Eun-ho, also in this exhibition. There is no illusion of depth, so the girl seems to be superimposed over the thin branches around her. All the color concentrates on her figure, with the darkness of her hair and the red and green of her kimono, standing out in an otherwise pale background. Her hair is beautifully arranged with a flower bow. The way her head is bent directs the viewer towards the middle of the painting, where the girl is holding a butterfly, stroking it delicately: metaphorically symbolizing the transformation of girls into womanhood.

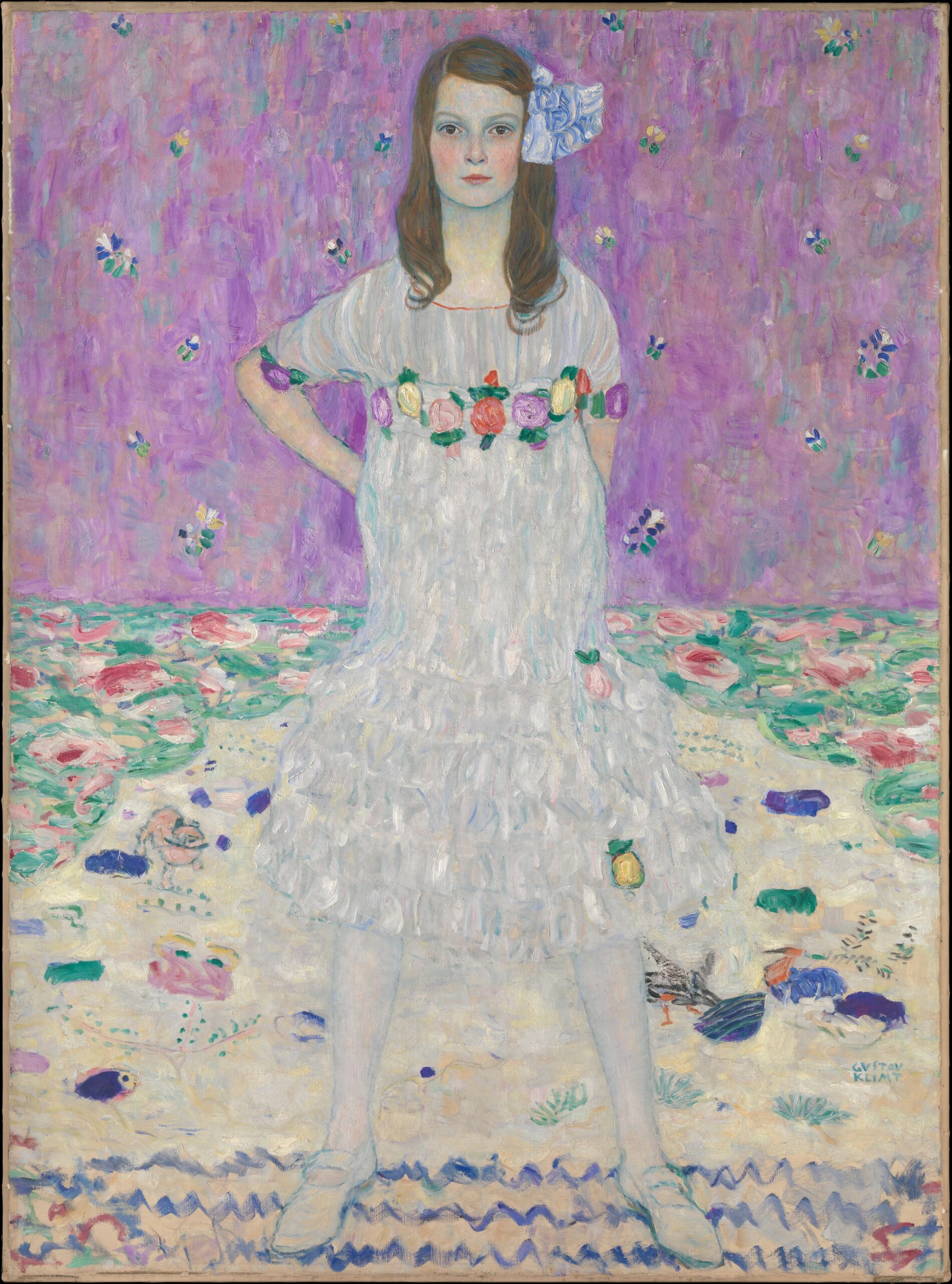

Gustav Klimt, Mäda Primavesi (1903-2000), 1912-13. Oil on canvas, 149.9 x 110.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Gift of André and Clara Mertens, in memory of her mother, Jenny Pulitzer Steiner, 1964.

The eight-year-old Mäda came from a wealthy family, who were patrons of Viennese art and design. The dress was created by Klimt´s partner, avant-garde fashion designer Emilie Flöge, at his suggestion. Even though Mäda considered herself a tomboy, she is wearing quite a fancy dress with flowers adorning the sleeves and belt. She also has a blossom on the side of her head. Her “supergirl” half pose and how she looks at the viewer conveys a sense of confidence, which makes her look older than her years. Many sketches were made before the final painting, with different poses, costumes, and backgrounds. There are some Oriental motifs on the wall and the rug is very colorful, as in many of Klimt’s paintings, but the viewer’s gaze is drawn in by Mäda’s powerful stare.

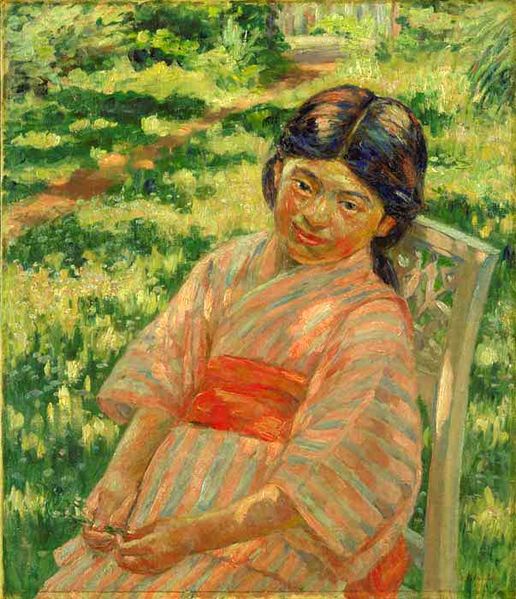

Kuroda Seiki, Sunbeams Falling through Leaves, 1914. Oil on canvas, 53.2 x 45.8 cm. Tokyo National Museum Kuroda Memorial Hall, Tokyo, Japan.

This painting was submitted to the 8th Bunten Exhibition in 1914, which was an officially sponsored national exhibition inspired by the French Salon. The girl in the portrait is called Kimiko, who was the artist Kuroda’s relative, as he recorded it in his diary when he began the painting. She is sitting in a chair outdoors in a garden, under something which provides shade for her, although some rays shine on her hair. On her left, there is a path that seems to lead to a forest clearing. Kimiko wears a light orange kimono with yellowish stripes and a wide orange belt called an obi, which is tied at the back. Kimiko seems to be sitting in a relaxed position while holding some green leaves in her hand. She is half-smiling, which gives the painting a tender air.

Amrita Sher-Gil, The Little Girl in Blue, 1934. Oil on canvas, 48 x 40.6 cm. Private collection.

In 2018, Sher-Gil’s 1934 portrait The Little Girl in Blue sold for 187 million rupees (2.6 million dollars) at Sotheby’s auction in Mumbai. The portrait depicts the artist’s eight-year-old cousin, Lalit “Babit” Kaur, who was fondly referred to as Babette. Quite amazingly, actual commentary from Babette exists, talking about the painting: “It was a beautiful morning,” a nonagenarian Babette recalled. “It was mummy’s idea… I was made to sit in the garden and pose [and I] absolutely hated it.” This is somewhat obvious by her expression, perhaps annoyed, perhaps disinterested: Babette’s head turns away. Her vibrant blue top appears in stark contrast to the figure’s solemn gaze and passive posture. A first-person account of posing for an artist and having their portrait made by a girl is exceedingly rare.

Kim Eun-ho, Miindo (A Beauty), 1935. Ink and color on silk, 143 x 57.5 cm. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Eun-ho’s portrait is an anonymous or imagined figure, a type of painting used to reflect beauty ideals about Korean women. It is a full-length portrait of a woman outdoors by a tree with some flowers at her feet. She looks like an ethereal figure with her delicate face and hands and her skin is as pale as the background behind her. She seems to be compressed between the tree and the front of the canvas. She looks at the viewer while holding her skirt and red breast-tie.

The painter allows for some touches of bright color which stand out, such as the blue tips of her shoes, the green half of her dress and the blue at the end of her sleeves. There are very few paintings of Korean women prior to the 20th century. Due to female modesty and a strict separation of the sexes, it was deemed inappropriate for women to sit for a male artist.

Irma Stern, Malay Girl, 1938. Oil on canvas, 56 x 57.5 cm. Private collection.

This is one of many portraits that Irma Stern created from her travels during her lifetime. It is clearly from the Expressionist movement, where emotions came before the expression of reality, as this particular portrait conveys so well. A young girl is shown looking directly at the viewer against a bold and vibrant orange background. Her simple dark purple blouse contrasts with the sitters’ warm skin tones: her dark hair frames her face. It is unclear if she is sitting or standing, and her hands are not visible. The way she is looking out with her honey-colored eyes is captivating and invites the viewer to wonder what she might be thinking.

Trần Văn Cẩn, Em Thúy (Little Sister Thúy), 1943. Oil on canvas, 60 x 45 cm. Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum, Hanoi, Vietnam.

The title of the painting names the girl in the work as Little Sister Thúy, although she was actually the artist’s niece. Thúy was only eight years old when she was first portrayed and was painted by the artist again when she was in her twenties. Thúy is leaning forward looking directly at the viewer, holding her hands together on her lap. She is in an interior setting in which only the colorful background is visible.

Thúy seems petite in comparison with the chair she is sitting on, a recurrent way to show youthfulness and delicacy. Her dress is pinkish, which contrasts with her dark hair and her black wristband, the only accessory she is wearing, as well as the brown frame of the chair. This is the most celebrated painting of the artist, Văn Cẩn. The artist was a founding member of the Foyer de I’Art Annamite. In 2004, the painting was restored and Thúy attended the unveiling ceremony.

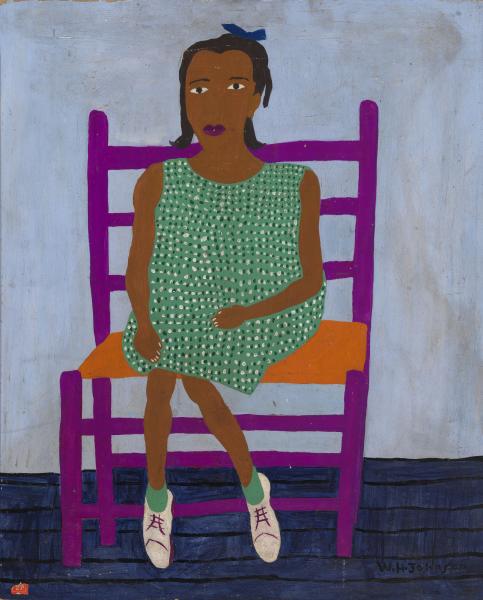

William H. Johnson, Anna Mae, ca. 1944. Oil on paperboard, 73.6 x 60.6 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C., USA. Gift of the Harmon Foundation, 1967.59.631.

This painting depicts a solitary, seated young girl called Anna Mae. She is simply but neatly attired in a sleeveless green dress with white and green dots. Small in comparison to the chair, Anna Mae can only touch the floor with the tip of her shoes. Her hair is down and on top of her head she wears a blue ribbon. Her facial expression seems quite serious.

This painting can be categorized in the ‘conscious naiveté’ style in which Johnson produced part of his oeuvre. These are simplistic in their nature and only use a few colors. Johnson favored painting African American subjects. He painted a series of portraits of seated women staring directly at the viewer, which Anna Mae might be a part of.

References

Art Fund. “Henrietta Laura Pulteney by Angelica Kauffman.”

https://www.artfund.org/supporting-museums/art-weve-helped-buy/artwork/5586/henrietta-laura-pulteney.

Berman, Greta. “Beauty and Truth in Renaissance Portraiture.” The Juilliard Journal.

http://journal.juilliard.edu/journal/beauty-and-truth-renaissance-portraiture.

Christies. ”Lucas Cranach The Elder Cranach 1472-1553 Weimar.”

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5056178.

Davis, Charlotte. “A Brief Timeline of 20th Century Visual Art Movements.” The Collector.

https://www.thecollector.com/a-brief-timeline-of-20th-century-visual-art-movements/.

Dobrzynski, Judith H. “Masterpiece: The Girl With the Sidelong Gaze.”

http://www.judithdobrzynski.com/19109/masterpiece-the-girl-with-the-sidelong-gaze.

English Heritage. “Women in History: Dido Elizabeth Belle.”

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/women-in-history/dido-belle/.

Grovier, Kelly. “Velázquez’s Las Meninas: A detail that decodes a masterpiece.” BBC Culture.

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20201015-velzquezs-las-meninas-a-detail-that-decodes-a-masterpiece.

Hirshler, Erica E. Sargent’s Daughters: The Biography of a Painting. Boston: MFA Publications, 2009.

https://collections.mfa.org/objects/31782.

Iran Chamber Society. “History of Iran: Women in the Safavid era.”

http://www.iranchamber.com/history/articles/women_safavid_era.php.

Kaplan, Howard. “Food for Thought: Melons, Mangoes, and Mughals.” Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art Blog.

https://asia.si.edu/food-for-thought-melons-mangoes-and-mughals/.

Kee, Joan. “Modern Art in Late Colonial Korea: A Research Experiment.”

https://modernismmodernity.org/articles/research-experiment#_edn19

Kensington Palace. “Queen Anne.”

https://www.hrp.org.uk/kensington-palace/history-and-stories/queen-anne/.

Liu, Yang. “Captive Beauties: Depictions of Women in Late Imperial China.” Arts of Asia (2020). https://www.academia.edu/43131810/Captive_Beauties_Depictions_of_Women_in_Late_Imperial_China.

Marshall, Peter.“The British Presence in India in the 18th Century.” BBC History.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/east_india_01.shtml#two.

National Gallery of Art. “Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474/1478.”

https://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/da-vinci-ginevra-de-benci.html.

National Gallery of Art. “Ginevra de’ Benci [obverse], c. 1474/1478.”

https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.50724.html.

O’Toole, Sean. “In search of Irma Stern, whose paintings still embody the contradictions of South Africa.” Apollo Magazine. https://www.apollo-magazine.com/irma-stern-painting-south-africa-sean-o-toole/.

Saint Louis Art Museum. “Portrait of a Young Woman.”

https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/20200/.

Sardar, Marika. “The Arts of the Book in the Islamic World, 1600–1800.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/isbk/hd_isbk.htm.

Seiferle, Rebecca. “Baroque Art and Architecture Movement Overview and Analysis.” The Art Story. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/baroque-art-and-architecture/history-and-concepts/.

Simons, Patricia. “Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture.” History Workshop, No. 25 (Spring, 1988). Oxford University Press.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4288817.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. “Young woman with a spray of lilies.”

https://asia.si.edu/object/F1932.64/.

Sorabella, Jean. “Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/port/hd_port.htm.

Southampton City Art Gallery. “Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1532 – 1625), The Artist’s Sister in the Garb of a Nun.” https://www.southamptoncityartgallery.com/object/sotag-197914-3/.

Stepp, Emily. “Gender Portrayals in Renaissance and Baroque Art (And Why They Matter).” Medium. https://medium.com/@emilystepp12/gender-portrayals-in-renaissance-and-baroque-art-and-why-they-matter-67283368d79c.

Tate. “Mary Beale, Portrait of a Young Girl, c.1681.”

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/beale-portrait-of-a-young-girl-t06612.

The British Library: Asian and African Studies Blog. “Portraits of Dara Shikoh in the Treasures Gallery.”

https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2017/06/portraits-of-dara-shikoh-in-the-treasures-gallery.html.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Mada Primavesi (1903-2000).”

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436819.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Portrait of a Young Girl.”

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10406.

The Walters Art Museum.”Portrait Of Maria Salviati de’ Medici and Giulia de’ Medici.”

https://art.thewalters.org/detail/26104/portrait-of-maria-salviati-de-medici-with-giulia-de-medici/.

V&A. “Japanese Woodblock Prints (ukiyo-e).”

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/japanese-woodblock-prints-ukiyo-e.

Yeh, Susan Fillen. “Mary Cassatt’s Images of Women.” Art Journal, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Summer, 1976).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/776228.

Credits

This exhibition was curated by Amber Barnes, written and researched by Sadie Dallas, Schillica Howard, Jennifer Lee, Alicia Garcia Pajares, Ashley E. Remer, Sophie Small, and Janice Yap.