As we discovered in our STEM Girls exhibition, girls and women have been working in the sciences for thousands of years, and we have all benefited from their contributions. But being in STEM fields requires more than just science, technology, engineering, and math skills. It requires something that benefits exponentially from the skills found in the arts.

In fact, if we think about the sciences and arts, they are really very similar. All require dedication, creativity, ingenuity, and curiosity. They require making connections and integrating parts into a whole — a talent that most girls have. When given the opportunity to combine and flourish, these skills can help us create a better, more colorful world.

The difference between science and the arts is not that they are different sides of the same coin…or even different parts of the same continuum, but rather, they are manifestations of the same thing. The arts and sciences are avatars of human creativity.

And Mae would know, since she was a doctor, dancer, and the first African American woman in space. She discussed her view on how the arts and science should be taught together during her TED Talk in 2002, which is featured at right.

Additionally, research has shown that Nobel laureates in the sciences are seventeen times more likely than the average scientist to be a painter, twelve times as likely to be a poet, and four times as likely to be a musician. This makes for very interesting lives and opens up human potential to infinite possibilities.

What is STEAM?

STEAM is the inclusion of the arts to the traditional program of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Adding arts to the STEM acronym was an idea of Georgette Yakman, an early founder of the movement.

Georgette began her career as a graphics and clothing designer. She later found that she loved teaching, especially technology classes. However, while studying the common factors of teaching across STEM disciplines, Georgette discovered that each STEM field requires students to develop skills they needed to continually adapt to new developments in STEM fields. These skills are commonly found in the arts, and thus was born STEAM.

Making STEAM a formal learning approach was first developed at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). They believed in creative, collaborative and experiential problem solving in order to create the leaders, innovators and educators of the new millennia.

And the evidence backs this up. A 2008 report from DANA Arts & Cognition Consortium found that training in the arts improves math and reading scores and boosts attention, cognition, working memory, and reading fluency.

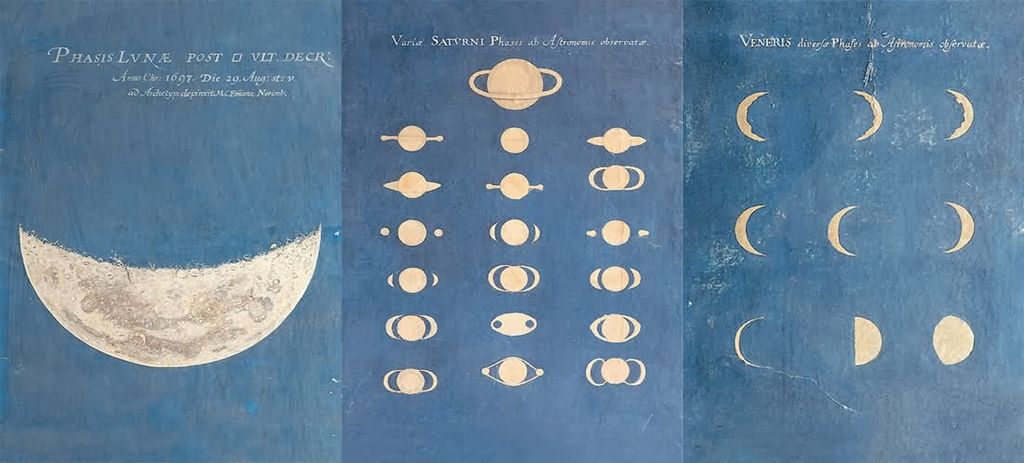

There are many ways the arts and sciences mix. Design is the most obvious, but there is also the mathematics of music, the chemistry of object and building conservation, the art of biological illustration, astronomic charting and photography. Hillary Hanel explores STEAM’s concept, its effects on learning, and amazing ladies in the field in the November 2015 episode of our podcast series, GirlSpeak:

Now, join us as we explore the many diverse ways that STEM + Arts + Girls = STEAM Girls.

STEAM in History

The Arts and Sciences have been together, perhaps since the dawn of time. The true beginnings of STEAM, however, began in the 15th century, a time known as the Age of Exploration.

It was an age when major advancements in navigational equipment led to the discovery of entirely new worlds — both on our own and beyond. Global exploration fostered an increased awareness of our lives and the place we held within our world — including explorations of our own bodies, the transmission of cultures between the continents, and the scientists who spent hours contemplating the heavens. Of all these scientists, there is one whose name is immortalized: Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo da Vinci

For an interesting story on this painting, check out our blog.

While not a woman, Leonardo da Vinci has served as an inspiration for countless generations of artists and scientists — so we’ve decided it is only fitting to include his work in our discussion of the history of STEAM.

Leonardo was born in Florence, Italy, in 1452 — the “bastard son of a peasant,” as some would call him. Not much is known about him until he became an artist’s apprentice at the age of 14 — learning drawing, sculpting, and carpentry amongst the artistic masters of the Renaissance. By the 1480s, Leonardo was being commissioned to paint altarpieces, instruments, and other works. After traveling to Milan to deliver a gift of peace, he became an architect and engineer, continuing his paintings in his free time.

Leonardo would blend the arts and sciences throughout his career — from designing cathedral domes and new inventions to drawing maps and painting works now housed in museums around the world. He also made many scientific discoveries, documented in nearly 2,500 drawings and 13,000 pages of notes — including studies of the human body. Some of his inventions would foreshadow, and perhaps inspires, future discoveries and technologies: a self-propelled cart (the car), a diving suit, and a flying machine (airplane).

Despite humble beginnings, Leonardo became one of the greatest human minds of all time — and he loved the sciences and art, especially when combined. As Leonardo stated,

“Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses — especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

But Leonardo wasn’t the only STEAM master in history. There were many, many others — including several girls! Check out our timeline below to see incredible STEAM girls from history:

Throughout this history, STEAM has had two sides — integrating the arts into science, and integrating science into art. And there are so many incredible girls and women on each side whose work demonstrates that STEM + Art open up new realms of possibility.

The next two sections explore these integrations, including profiles of and interviews with incredible women to inform and inspire the next generation of STEAM girls.

STEAM Today

Many artists use science in their works, and many scientists use art. Often, these fields intersect so well that it blurs the lines between them!

And across these fields are many incredible women showing us that by combining STEM and the Arts, we unleash a powerful creative force that explores the world of the past and present while opening up our future to new, exciting possibilities. Use the toggles below to explore the work of these incredible women.

Art + Climate Change: Glacier Girl

19-year-old Elizabeth Farrell is known as ‘Glacier Girl’ – an artist who uses visual environmental activism and digital technology to raise awareness about climate change.

“Climate change is almost invisible, particularly if you live in cities, so making it something visual is really important. Whether we can see it or not, it’s not a future thing, it’s happening now, and I think that’s hard to grasp.”

Through social media, Glacier Girl has gained a cult following dedicated to spreading her message. She translates academic research into photographs and installations that tackle topics like big industry, modern capitalism, and our precious position on earth. Check out her work in the video below:

Art of Conservation: Megan Griffiths

Megan.

Megan Griffiths is a conservation technician at the Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center in Omaha, Nebraska. The Center is a division of the Nebraska State Historical Society, but it is also a regional center. This means that in addition to working on the State’s collections, they also work with museums, libraries, and private individuals in Nebraska and the surrounding states. They treat objects, paintings, and paper. Megan is a technician, which means she can do basic treatments under the supervision of a conservator, primarily in the Objects Lab. She is also in the process of applying for graduate school in conservation.

First, tell us a little about your background in museum conservation.

After a long and winding road and much indecisiveness, I graduated from the University of Tulsa with a Bachelor of Arts in Art History. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do with my degree, but I knew I wanted to work in the museum field. I was really curious about Art Conservation, but I knew it would be a lot of work to get into a program and I wasn’t sure if I would like it enough to invest the time and money. As a compromise, I went to graduate school at the University of St Andrews and got my Masters in Museum and Gallery Studies. I was able to do a condition survey on a rare book collection at the school’s library and I wrote my thesis on paper conservation. The program allowed me to focus on the area I was interested in—conservation– while providing me with the basics I would need to work in a museum in any capacity. When I graduated, I started looking for a job that would allow me to get the in lab conservation experience I would need to get into a conservation program, and I ended up as a conservation technician at the Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center in Omaha, NE.

The Ford Center is a division of the Nebraska State Historical Society, and we are a regional lab that offers services to museums, libraries and private individuals in the area. We have a lab for paintings, paper, and objects. Anyone who wants us to treat their artifacts, we can help them!

How did you first develop an interest in museum conservation? Did it start with a love of science, art, history, or something else?

My first memory of hearing about Art Conservation was watching the movie Ghostbusters II! It wasn’t very accurate, but it definitely stuck with me as a kid. Then when I was 16, I was able to go on a class trip to France and Italy. It was in 1999, so everyone was getting ready for the big Year 2000 celebrations and lots of buildings and works of art were being cleaned at that time. That really interested me. As a kid, I first wanted to be an artist, and then I wanted to be a paleontologist, so I always loved art and science.

Megan working with a turntable to conserve an object.

It’s really important for conservators (and technicians like me) to know about the materials they are working with. For instance, they need to understand the solvents they use to clean art work, because they might want to remove the varnish from a painting, but they definitely don’t want to remove the paint! They also have to know how the materials of the object itself interact with each other. Or what types of adhesive will work best to put an object back together. There is a lot to learn! And conservators need a background in the arts because hand skills, drawing ability and color matching are really important when making repairs and filling losses.

What has been your most challenging conservation project?

As a technician, I only work on pretty basic treatments. I’m sort of like a nurse. I can clean the wounds and put on a bandage, but I can’t perform major surgery. When I was first hired, my main responsibility was cleaning metal objects from a sunken steam ship from 1865. I had to remove an old protective coating that was put on when the objects were excavated in the 1970s, then I had to remove the rust that had accumulated, and then put a new coating on. Overall, I treated over 4000 objects in 3.5 years! That was a pretty big challenge!

But my colleagues have had some challenging projects, especially working with modern materials. Plastics are really difficult to work with because they degrade easily and there isn’t much we can do to stop it except keep it in the dark away from oxygen. But that doesn’t work for objects you want to see and look at. So we have to discuss with clients the limits of what their objects can handle.

There has been a big push for STEM in schools recently. What are your thoughts on adding the arts to make STEAM?

I love it! The arts and sciences are both so important! Not only do the arts offer so many wonderful things in life for us to enjoy, but the arts and sciences can complement each other. Artists can use science to learn more about the materials they are using so they can make their artwork last longer for future generations to enjoy. Or a dancer can use anatomy to understand how the body moves and how muscles work together. The arts help you learn critical thinking and problem solving. What scientist wouldn’t be helped with having new ways of looking at the world to help find that next great discovery? Arts and sciences are mutually beneficial and help us understand the world around us!

Do you have any crazy stories from working on artifacts and artworks?

When I was working on objects from the steamship, a lot of the items were containers than had held food. Most of the food had been removed when the objects were excavated, but sometimes, things remained! I once had to scrape remains of 150-year-old lard from a lard tin. That was pretty gross!

Another fun story was when we had some clients bring in a couple bullets they believed were from the Civil War. The bullets were inscribed with writing, but the letters were difficult to read, so the clients just wanted us to look at them under a microscope to see if we could figure out what they said. As I was looking at them under a microscope, I noticed that both the bullets had holes in them with rounded piece of glass inside. Because I had been shown objects from the steamship collection that had a similar piece of glass, I knew that these were very small lenses. I held one up to the light, and sure enough, there was a magnified image of a tiny photograph showing several Civil War monuments. By looking at the images, we were able to confirm the inscription on the bullets! It was really exciting to see because the clients hadn’t even noticed the lenses before and we were able to solve the mystery.

Megan with a tool of the trade — a vacuum!

If you could give one piece of advice to a little girl who loves both the sciences and the arts, what would you tell her?

There are so many opportunities out there for you! Don’t let anyone discourage you from doing exactly what you want to do with your life, be it arts, science or both! You never know how you might be able to incorporate one into the other and what amazing things might result.

And don’t be discouraged if you don’t yet know what you want to be when you grow up. Not only is trying new things fun, but it is 100% ok to change your mind!

Is there anything else you would like to share with the Girl Museum community?

There are so many fascinating women artists and scientists out there you can look to for inspiration. They came from a wide variety of backgrounds and have great stories about how they got to do what they do. These women literally changed the world, and you might, too!

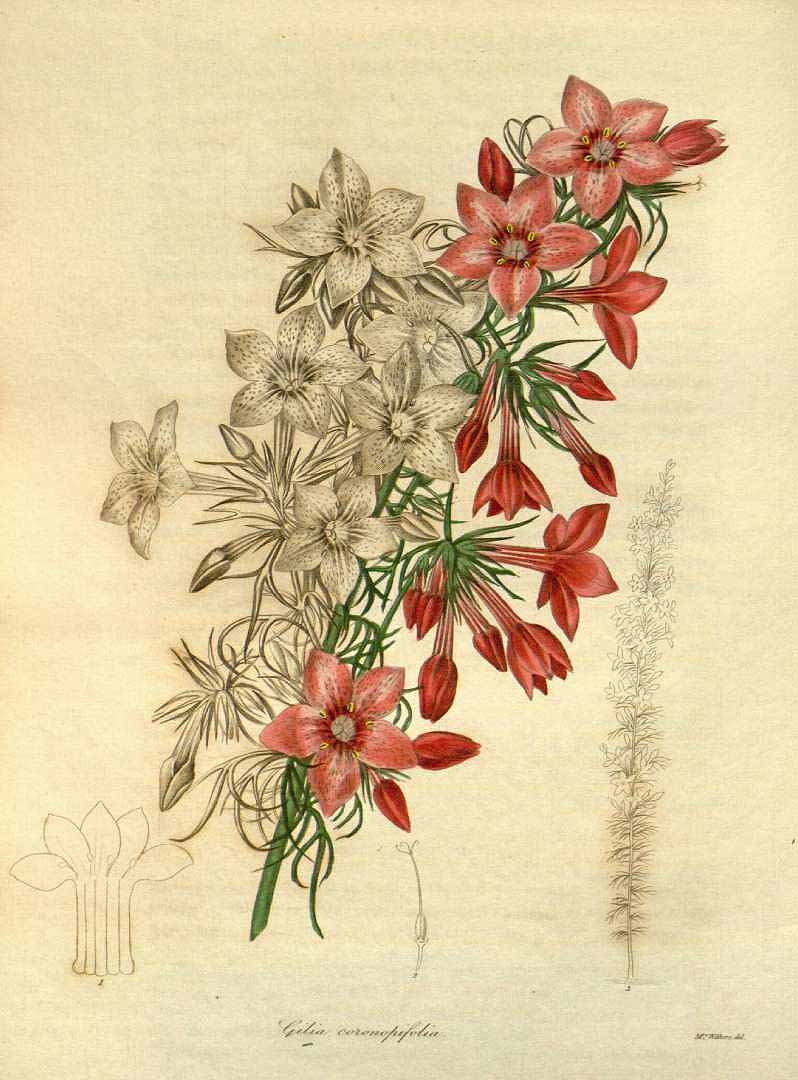

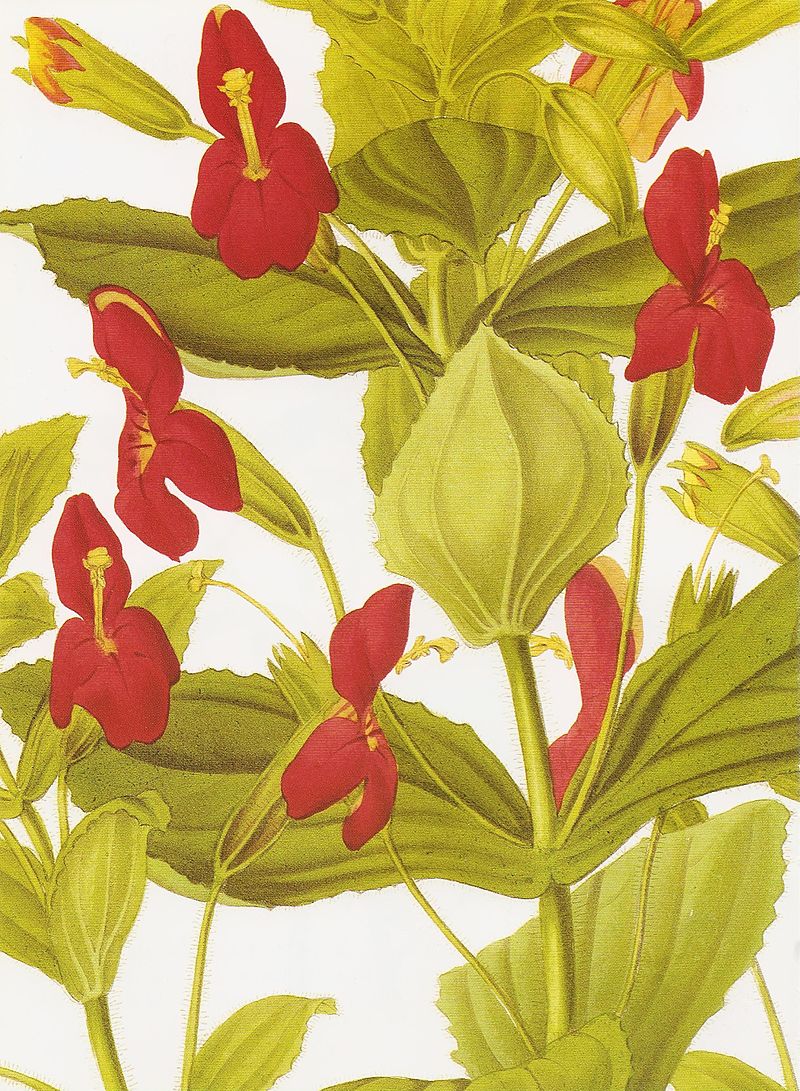

Documenting Nature: Jane Wells Webb Loudon

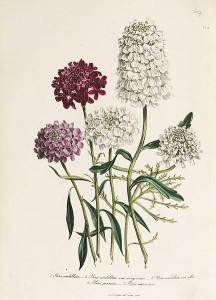

Illustration by Jane Loudon from The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Annuals, 1842.

She met and married John Loudon, a horticulture writer who loved The Mummy! so much that he sought her out. They worked together on books and in their garden. Jane learned all she could about horticulture, but found that there were no books available for beginners like her. So she wrote gardening manuals for beginners that she illustrated herself, such as The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower-Garden (1844). Jane’s books inspired women throughout Britain to take up gardening as a hobby, and her illustrations were so popular that they were used for decoupage on trays, lampshades, and tables. Jane died in 1858, and she is remembered as one of the most successful botanical illustrators and educators in history.

Everyday Design: Lisa C. Clark

Lisa C. Clark

First, tell us about your Thinker Collection. How does it combine art and science?

Thinker Collection offers designs highlighting innovations in STEM: Science, Tech, Engineering and Math, digitally printed pixel-by-pixel onto a variety of fashion and accessories, poster art, consumer tech products, home goods, stationery and more product categories. It is intended to draw from the scores of “-ologies” disciplines that comprise S-T-E-M and thus offer a vast selection of possible topics that are also ever-changing and global.

How do you come up with the unique designs seen on your Thinker Collection products?

I research what’s current in start-ups, new inventions, innovations, discoveries, hot topics at STEM companies and in K-16 education, “-ologies” of interest as major fields of study. Start with existing images, sketches or line art and massage/change them, combine and re-combine them into totally new art as emblematic designs, art pieces and pattern repeats.

Anything can spark: Listening to “Science Friday” on NPR, a conversation at an event or tradeshow, a topic that seems to pop up over and over again in Web social diasporas, parents’ concerns over their students’ toughest/most disappointing school topics.

Your Tshirts have been worn by Sheldon on the Big Bang Theory. How cool is it to see something that you created on a popular television show?

It’s very cool. The opportunity came up in 2008 when I was launching the brand at “Fiesta del Sol,” a beach street festival in north county San Diego, at a retailer. A man walked up out of the crowd, looked at my first designs and said, “I’m the lead audio engineer for “The Big Bang Theory” in LA. I want to show your shirts to my producer, because I think they should be on the show.” Warner Brothers bought shirts with 16 designs and started costuming Jim Parsons in them in early 2009.

What’s even more fun is that my customers will call and say, e.g., “I was on a flight from New York to Sao Paolo and saw your shirt on a TBBT episode in-flight over the Caribbean,” or, “I’m the engineering lead for a nanotech group and I want your “Nanotubes”© “Sheldon” shirts for my entire department.

Thinker Collection has sold direct to customers on five continents, including folks at national labs and top STEM universities, people affiliated with MENSA and employees of Silicon Valley’s hottest companies.

What are your thoughts on STEAM? There has been a big push for STEM in schools, how important is it to add the arts?

All environments that surround us, from Main Street stores to mankind’s greatest engineering and artistic building feats, are combinations of STEM and artistic design. Even engineers globally couldn’t stay away, adding their artistic talents as chip design “signatures.”

Science and art, as two sides of one brain or two sides of the same coin, are intertwined and equals in human experience; as long as people employ logic and reason but are impacted and expressive emotionally, STEM-to-STEAM will be essential. The world’s greatest polymaths — Archimedes, Leonardo Da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin — have understood this.

As a little girl, were you interested in art and science, and if so, which were you more drawn to?

My genome is very mid-brain. The women in my family were artists and designers – my mother was a NYC textile and fashion design executive on Seventh Avenue for decades, and the men in my family were mechanical and electrical engineers and inventors – my grandfather was lead engineer at Western Electric for his career, and patented the trans-Atlantic co-axial cable that runs along the Atlantic Ocean floor from the United States to Europe.

As a little girl I was initially drawn to art via handcrafts (sewing, knitting, needlework, fashion), and as an older girl to design and building: Spirograph, Lincoln Logs, Erector Sets, Tinker Toys. The boys in my family were all-things-that-go, “take it apart / put it together / how does it work?” people: My brother put his first Briggs and Stratton motor on a banana seat bicycle when he was 10 and my cousin investigated vacuum cleaners and later made airplanes and the airlines his career.

By high school biology I drew my first cells under a microscope and they were really good. That sparked an interest in science which led me to pursue a (short-lived) biology pre-med major at Georgetown University.

Have you had any influential teachers or mentors that have helped to spark your interest in STEAM?

After graduate school in Washington, D.C. I made my way to Silicon Valley and eventually was in corporate market development at Sun Microsystems in Mountain View, CA, in the Education and Research Marketing group. My group manager there challenged and enabled me to take over architecting and launching Sun’s first retail channel selling its new SPARCstation engineering workstation desktops to students, faculty and staff at the top STEM universities and research labs worldwide. I was able to combine consumer and tech marketing and was exposed to folks all through STEM, and circled back to it as a skeletal design structure around which to launch my company, having seen a market void and opportunity in textile and surface designs on STEM topics.

Where do you think the future of careers in STEAM lies?

I think there has been a pendulum swing over the past decade from intense professional focus on marketing, then on finance/numbers/measurables and currently on engineering as “everybody must [somehow] code.”

As teach-and-learn paradigms of the American educational system are being exploded, revisited and redesigned, the pendulum will once again readjust toward recognizing the variety of definitions of “well-rounded” and incorporate the vast differences in how people learn. An economic system once based on a corporate model but increasingly based on entrepreneurship and lifetime work self-sufficiency has helped drive the Maker Movement which harkens back to the guild system of journeymen and apprentices – people producing and working with their hands, single product at a time versus assembly line. This plus people “finding new uses for found objects” and re-purposing which is, at its essence, nothing more complicated than marketing asking, “What are all the things we and customers could possibly do with xyz product?”

I’m a great proponent of STEAM because of the expansive ways artists think. (When folks on LinkedIn comment about “thinking outside the box,” I like to respond wondering, “You mean there’s a box?”)

For all these reasons I think the future of careers in STEAM – individuals coming up with The Next Great … — may be stronger at this point in time than it’s ever been.

What advice would you give to young girls who love both science and art?

I came to launching my business at a later point in life – in my mid-40s and after a household break-up and life change necessity. But in the process of doing so I also took time to go on a personal inward journey of once again getting to know myself, that is, the me that was as a young girl. I took months to think long and hard about how I’d spent my days, how I played and what with, what I built, designed and created – I went in search of any common threads of interest through each year of my life so far. And that search allowed me to create a company that has revealed itself to require the sum total of most every job I’ve ever had through life as I shifted from one side of my brain to the other, and back again: Painter, cashier, hand knitting fashion designer, legal assistant in international trade, strategic marketing consultant, tech marketer in STEM, interior/home products designer.

My advice to young girls would be: If I could take a needle and thread and combine together such a diverse background of experiences and interests, so can you. So make a list of every single thing you’ve ever loved doing in your life – everything that’s ever given you great happy joy in your day, everything that’s ever made you so engrossed that time just flew by you were so content. See which of those things include any tiny tidbits related to science and art, go find people who have done any parts of any of those things and ask them, “How did you get here?” Ask them to tell you their stories through the years of their lives. They will show you how one idea leads to a contact and a concept and a school course and a business to look at and …. They will show you how it might not all make sense at first, but with each odd experience you’ll be building toward the sum total of the best of what’s inside you to be enriched, encouraged and pursued. And if there’s no position title, no job function, no company that neatly offers exactly what is the summary of who you are and what you love, Just Go Do It – and make your own.

Is there anything else you would like to share with the Girl Museum community?

One of the most powerful lifelong learning advantages I’ve experienced through my own journey has been to practice the habit of detailed observation – being very, very aware of all that’s going on around you. Consciously study human behavior – read about it and take classes, as young as possible and as much as you can. And observe and actively think about what it’s taken to create virtually every single manmade thing you see around you in the world. The immensity of what people have accomplished on Earth before you and I got here is astounding. And it all took STEM and STEAM.

From the movie “Dead Poets Society”: Carpe diem, girls. Robin Williams quoted the poet Walt Whitman: “That the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?” If it is in STEAM, what a legacy you may leave to the world.

Pottery: Susannah Goodman

Susannah Goodman is an artist-potter and art educator in Detroit, Michigan.

First, tell us a little about your background in art and art education.

First, tell us a little about your background in art and art education.

I started out life in the performing arts. I learned disciplined practice and developed a commitment to collaborative work through playing cello in the orchestra at my school, beginning in 4th grade. My first job, from age 14 to 18, was working in theater tech. It was a rush: working in community with dozens of other people to pull of something great and grand and wonderful. But also, I enjoyed the variety of skills I was able to learn and make use of: from the technologies of sound and light boards, to mechanicals of flys and curtains, to carpentry and set production, I was able to explore a world of skills within one art form. That same range of materials and skills is what has kept my interest in clay; building wooden shelves, casting bricks for kilns, repairing electrical components, foraging for clay in the woods, and even organizing people to fill studios and kilns.

How did you first develop an interest in pottery and other types of art?

An amazing teacher in high school introduced the idea of discipline into visual art. I wasn’t always great at wheel-throwing, but I loved the community of the art room. I watched as clay enabled students to pass an idea around, imitating each others’ pots and having creative dialogue. I didn’t expect to study ceramics in college, but another inspiring set of educators guided me along that path. Finding myself in North Carolina for college, a historic place for pottery, all the way back to the indigenous Catawba people, clay was history and present. I spent much of my college years making art inspired by the rich history of the region.

Many people don’t realize that there is a very scientific part of working with clay, kilns, glazes, etc. Tell us how science plays a part in the process of creating pottery.

Many people don’t realize that there is a very scientific part of working with clay, kilns, glazes, etc. Tell us how science plays a part in the process of creating pottery.

Pottery, like many other art forms, is an exploration of materials. Each pot I make is a dialogue in engineering between me and the clay: I ask it, “Will you take and hold this shape?” and it gives me a clear answer, by either holding the shape or flopping over. In this way, each failure becomes an opportunity to ask “Why did that happen?” and “How can I change the design to make this better next time?”

Beyond the shaping of the clay, every material that goes into making pottery matters. Each clay is different, containing a wide range of earth elements. Clays must be tested for shrinkage, porousness, and strength both before and after firing. Each clay has a particular range of temperatures at which it will be strong, food safe, and stabile. The ingredients of a clay can be changed to enhance any particular quality, as long as you know how to tinker with the recipe. The investigative process applies to glazes and kiln firings, adding in glass, colorants, fire, and about 2200 degrees fahrenheit to the mix. That’s why potters are really chemists in disguise. A good potter will look at each kiln load as a body of evidence, speaking of all the component parts and how they brought about this outcome, what was desirable, what was undesirable, what could be learned, and what could be changed.

When teaching pottery classes, do you incorporate science into your lessons?

When working with beginners, I try to make visible the microscopic parts of the ceramic process. There are so many things we can’t see that make our work successful or unsuccessful. Understanding the particular shape of clay particles, the way water behaves, and the way clay and glaze behave at high temperatures can shed much light onto the work.

There has been a big push for STEM in schools recently. What are your thoughts on adding the arts to make STEAM?

There has been a big push for STEM in schools recently. What are your thoughts on adding the arts to make STEAM?

Each of the disciplines is strengthened by its integration with the others. Science, technology, engineering and math are applied each and every day by great artists around the world. I believe the arts are an engaging sphere to practice, fail, analyze and engage again with each of the disciplines in STEM. It’s a natural combination.

Do you have any fun stories of “a-ha” moments with your students when they finally understand a new concept or technique?

I come from a family of scientists: physicists and neuroscientists and mathematicians and computer programmers. My sister, the neuroscientist, once told me, “The most exciting moment is never the ‘Aha,’ but almost always the ‘Hmm, thats strange…'”

I embrace the mystery of the ceramic process, and I try to share that excitement with my students. I encourage them to document their experiments, changing only one variable at a time for best results. When those moments of “Hmm, I didn’t expect that,” occur, I encourage them to probe deeper. Just like in orchestra, making great pottery is not about the finished work, one great performance or one beautiful pot, but about the journey of increasing your skill and understanding. It is a practice.

If you could give one piece of advice to a little girl who loves both the sciences and the arts, what would you tell her?

If you could give one piece of advice to a little girl who loves both the sciences and the arts, what would you tell her?

Every art, if you dig deep enough, is rooted in science and math. Go deep! Ask questions! Breaking the rules in any art form can be the most incredible learning experience. Find a good teacher: they don’t need to know everything, but they should point you in the direction to find the answers for yourself. Take notes! A great sketchbook, documenting each and every experiment/art project, is invaluable for future adventures. When something falls over or falls apart or looks terrible, take it as invitation from the universe to find out why and try again. In science and the arts, resiliency is key.

Science of Photography: Kassie McGlashen

Kassie McGlashen is a photographer, who spoke with Hillary Hanel about how art and science combine in her work with Kaptured by Kassie. Use the arrows in the center to scroll through her interview.

Kassie McGlashen is a photographer, who spoke with Hillary Hanel about how art and science combine in her work with Kaptured by Kassie. Use the arrows in the center to scroll through her interview.

First, tell us a little about your work.

This is a hard question. I don’t just focus on one type of photography or even one single medium so it’s hard to put a label on what I do. I normally shoot digitally, but have experience in film and many other alternative processes. I like to explore photography and image making across the board; the images I make usually come from a place of curiosity or a place of definition. I like narratives and story telling, I truly believe that because I have a hard time expressing things verbally, doing so visually comes natural to me. I am a person who has a lot of emotions and I think my work is usually a refection of my feelings, as well as those of others and society.

How did you first develop an interest in photography and other types of art?

I have always been a very visual person, who has always been interested in making things. I was always making art as a child, whether it was painting, making crafts out of found objects around the house or even designing new clothes for my dolls. And while I still enjoy all of these types of art, photography is the perfect blend of all of my interests and a way for me to express my creativity with my own personal way of seeing the world.

As silly as it sounds, I really started focusing on photography with the rise of social media. I have always had a disconnect with the way I saw myself and the way the world saw me, so when it came to describing who I was or showing photos taken of me, I was uncomfortable. I remember feeling like no one would understand because I could never express who I really was. So, I started taking photos to show it. I wanted people to know that there was a deep thinker inside of me and that I was a really creative person. I wanted my weirdness to come though but not in a way that would lead to judgment. Photography was my perfect answer.

There is a scientific side to photography that most people don’t think about. How is science important throughout your work?

Science, in general, is very important to photography in many ways. With film, it is very important to understand the chemical make up of the medium you are shooting on, as well as what you use to develop and print photographs. Most people don’t know that the whole basis of photography is based on silver. Silver nitrate particles are light sensitive and whatever is coated with them and however long it gets exposed in what pattern will determine what the photo will look like and the Silver will wash away in different layers according to exposure. The same goes for alternative processes. The cyanotype, for example, is a photographic process that uses the sun, or any UV light, to produce an image on anything coated with the perfect blend of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate and if you don’t understand how to mix the chemicals, you could be in trouble.

Science is also important to Digital photography in many ways. You have to be able to understand the mechanics of the camera and you have to be able to apply that to a real life situation. For example, if you are trying to shoot a moving subject without blur and with a flash, you have to know to set your camera to shoot under 1/250th of a second because of the speed of light, the flash will not be captured at a higher shuter speed and then you have to adjust your other settings accordingly.

What is your favorite part of photography?

My favorite parts of photography have to be 1. Coming up with the idea and 2. Seeing the finished product. Shooting is fun and editing can also be fun but both are tedious to someone like me, who is more right brained. I like to see the art for the art in its beginning stages and its final form.

There has been a big push for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) in schools recently. What are your thoughts on adding the arts to make STEAM?

There has been a big push for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) in schools recently. What are your thoughts on adding the arts to make STEAM?

I think adding the arts would be an amazing idea. Its so important to teach young girls these skills, and while I am kind of biased, I think that if anyone is having a hard time with something and needs a way to express themselves, art is the way to do it. If you can teach a girl to believe in herself and her feelings and you teach her that they matter and she can do something beautiful with them, go for it. Improving confidence through the sciences is so vital for young girls, but we also have to improve the confidence in their creativity and thinking outside of the box as well.

If you could give one piece of advice to a little girl who loves both the sciences and the arts, what would you tell her?

I would tell her that she has an amazing gift to see both the logical and the illogical in the world and to never give that up. There is so much that the sciences can teach a growing mind and the arts will just help it bloom. I’d hope to inspire her to pursue any and all of her passions regardless of what others think and not to think she has to just pick one path.

Is there anything else you would like to share with the Girl Museum community?

Just a huge thank you for letting me gush about what I love!

Sculpting the Past: Forensic Science and Art

Karen T. Taylor with historical sculpture of Bo Man, 2007

Actually, we can — by combining forensic science and art. Forensic facial reconstruction is the process of recreating the face of an individual from their skeletal remains. At first glance, it seems all science — but it involves a lot of artistry and, at times, historical research to ensure accuracy.

The field first began with two-dimensional reconstruction, where artists would sketch what they believed a person might look like. These sketches would be based on skeletal remains or descriptions from family and friends. Karen T. Taylor was a pioneer of this method, working for over 25 years to help solve criminal cases. She began as an artist and sculptor, attending the University of Texas School of Fine Arts and working as a portrait sculptor for Madam Tussaud’s Wax Museum. Karen then turned to working for crime labs as a forensic artist, during which she developed a method of two-dimensional reconstruction that involves adhering tissue depth markers on an unidentified skull at various landmarks, photographing the skull, and using the prints as the foundation for facial drawings.

Karen’s method would inspire three-dimensional facial reconstruction technologies, including F.A.C.E. and C.A.R.E.S., two computer programs that quickly produce two-dimensional facial approximations. Three-dimensional techniques also include sculpting a face from a cast of the cranial remains, using modeling clay and other materials to show us the faces of the past. This technique has brought to life many historical figures, including victims — like Jame, a young Jamestown colonist:

Writing Science: Mary Shelley

Manuscript page from a draft of Frankenstein, 1816.

Mary was born in 1797 in London, the daughter of novelist William Godwin and feminist philosopher-educator Mary Wollstonecraft. Raised by her father, Mary received an advanced education from her tutor, governess, and witnessing her father’s many intellectual debates. At the age of 15, she was sent to live with the Baxter family in Scotland, where she originally wrote the opening lines to Frankenstein. Around this time, she also met Percy Shelley — with whom she fell in love and secretly eloped to France.

At 18, Mary was living in Geneva, Switzerland, with Percy and Lord Byron, among others. One June evening, Mary stayed up late discussing the principle of life with her friends, at which point she was inspired by the idea of a corpse being re-animated. That night, she was plagued with dreams. As she stated,

“I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.”

Frankenstein was published in 1818, when Mary was only 20 years old, blending scientific concepts and debates with Romantic literature to become one of the earliest examples of science fiction. Her novel would go on to have considerable influence in demonstrating how scientific concepts can be readily explained to the populace through literature.

Mary would go on to write many novels, short stories, biographies, and travelogues, though Frankenstein would be her most remembered work.

Sustainable Design: Oli-Bo-Bolly

Olivea began sewing when she was 8 years old, and eventually combined her passion with her desire to contribute to the sustainability of the environment. She used unwanted clothing to create new designs — starting her own business at the age of 11.

In December of 2012, she made a doll using recycled materials for her art class. Her teacher loved it so much that he bought it for his daughter. Six months later, Olivea took a mission trip to Nicaragua with her family. She fell in love with the local people and wanted to put a smile on the face of every little girl she met. Upon her return, Olivea decided to combine all of her passions — making dolls to be gifted to little girls in Nicaragua, and selling some of her dolls to acquire funds for the donated ones. In 2014, she won seed funds to increase production and sell her dolls at local stores in Colorado. Later that year, she returned to Nicaragua and expanded her production to include 6 Nicaraguan seamstresses and a local tourist retailer.

Using the motto, “Buy a doll, give a doll, empower a woman by giving her a job,” Olivea now runs Oli-Bo-Bolly. Her business sells handcrafted, one-of-a-kid dollies — and for each dolly purchased, another is donated to a young girl in a community in need. Each doll carries the message, “You are beautiful, loved, unique, special, and created for a purpose,” inspiring girls around the world. She currently sends dolls and empowers women in Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Peru, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nepal, Thailand, and Australia.

Full STEAM Ahead!

The stories above show us that STEAM is all around us. Many of the greatest contributions to human knowledge have resulted from minds that STEAMed ahead, blending the arts and sciences to find new connections, create new inventions, and open our eyes to a world beyond what we ever could have imagined.

Today, many great organizations are working to help engage girls and develop STEAM skills. One is the WiSci camps, which took place in Rwanda during 2015. WiSCi, or “Women in Science and Innovation” is a joint venture of Girl Up, Intel, Microsoft, the Rwandan Girls Initiative, and the Secretary’s Office of Global Partnerships. Together, the organizations produced camps that advanced and expanded STEM opportunities for young African girls while empowering them with the knowledge and skillsets to be competitive during their careers.

Whether in the classroom, through extracurricular activities, or at home, the opportunities for girls to learn STEAM skills are increasing every day. And it’s a skillset that will always be in demand, as it empowers girls with creativity, ingenuity, and curiosity to successfully address the increasingly complex, multidisciplinary challenges of our future — and STEAM ahead to a brighter, better tomorrow.

“I had the opportunity to meet various phenomenal women from all over the world who have made it and are considered the “top dogs” in their fields and departments. They have made it single-handedly and have attained their respect as women — for example, Dr. Frances Colon holds a PhD in neuroscience and serves as the science and technology advisor to the secretary of state at U.S state department of state where she promotes the integration of science and technology into foreign policy dialogues. By doing this, she has broken down barriers and made her way into male dominated fields and boardrooms, and gained her respect not because she waited and smiled at everyone, but because of her confidence and competence.”

Are you a STEAM Girl?

Are you doing incredible things with STEAM? Share your STEAM story with us by emailing share@girlmuseum.org, and we’ll feature it on our blog and this exhibit!

Education Guide

Ready for some STEAM-inspired fun? Check out our downloadable STEAM Girls Education Guide for tons of fun activities related to this exhibit. And don’t forget — share your results with us and we’ll feature it on our blog and website! Email your completed projects, and any images or video, to share@girlmuseum.org

All of our activities align to US and UK educational standards. They are intended for use at home or in a diverse range of classrooms.

Credits

The curatorial team for this exhibition was Ashley Remer, Hillary Hanel, Tiffany Rhoades, Caroline Hall, Emily Holm, Michelle O’Brien, and Sarah Raine.

Special thanks to Kassie McGlashen, Lisa C. Clark, Megan Griffiths, and Susannah Goodman for their interviews and photos.

All photos and videos in this exhibit are used under (1) Creative Commons licensing, (2) Fair Use terms of U.S. Copyright law, or (3) with the express permission of the author.

Apps for STEAM Girls

Mobile Apps

Looking to dive into STEAM? Check out these websites and mobile apps that connect STEM fields with Art!

Algodoo is a 2D simulation software that invites students to create interactive scenes and inventions through playful cartoons.

Basket Fall invites you to discover physics by predicting angles, arcs and the effects of gravity.

Color Uncovered is an interactive book that explores the broad spectrum of color through art, physics, and psychology.

DIYNano (Grades K-5) invites kids to learn nanotechnology through step-by-step instructions and videos on how to create nano-based experiments.

DragonBox (Grades 1-5) “secretly teaches algebra” through increasingly complex math-related games.

Get the Math (Grades 7-10) combines videos, web interaction, and real-world scenarios to prove that – yes, you do need Algebra in life.

Hopscotch (Grades 4-6) is a Parent’s Choice Award winner that introduces coding to younger students and shows them how to create games, animation, and art.

How Many Saturdays? invites you to discover how we measure and experience time…and the variety of ways we could measure it.

Lightbot (Grades 6-12) teaches computer programming through puzzles and problem-solving tasks, like moving a robot through a maze.

MIT App Inventor is a web-based program that teaches students how to create their own mobile apps! It also includes resources for teachers to use in classrooms.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory website features different activities to teach students space-related STEM concepts. They also offer a variety of mobile apps.

Pocket Astronomy (Grades 6-12) is perfect for star lovers. You can take virtual tours of all the bodies in our solar system, and learn about different stars and astronomical bodies while watching the night sky!

Project Noah (Grades 4-12) combines physical and biological science with civic responsibility and journalism to help students contribute to a crowdsourced nature journal simply by taking pictures in their own neighborhoods! You can also join class and global missions to help achieve scientific research goals.

Sound Rebound uses color and puzzles to help you visualize how you experience sound!

Sound Uncovered (Grades 3-12) invites kids to explore the world of bumps, beeps, booms, and vrooms by placing them at the center of auditory experiments!

Stephen Hawking’s Snapshots of the Universe (Grades 4-12) combines astronomy and physics into fun video, audio, and interactive elements – all from the mind of Stephen Hawking.

The Radix Endeavor combines the fun of multiplayer online gaming with math and science, inviting kids to adventurously explore the island of Ysola by solving math and science problems. Includes a website with teacher tools for incorporating the game into classrooms!

Additional Resources

Try out STEAM

- 7 Maker Faire Exhibits Geared Towards Girls

- CryptoClub immerses students in cryptography & mathematics

- KcDStudios on Easy makes Elements – Experiments in Character Design Flash Cards that we love!

Exhibits

- WOMENTEK by The Lawrence Gallery at Rosemont College, 1998.

- Women of Vision: National Geographic Photographers on Assignment

- Fantastical Women (Artists in Science Fiction / Fantasy)

Organizations / Camps

- Pretty Brainy

- New York STEAM Girls Collaborative

- STEAM Girls Camp (California)

- Seattle STEAM School

- STEAM Education

- Wolf Trap uses artist residencies to increase the use of arts in STEM learning.

- Geeki Girl Gatherings teaches STEAM to middle school girls in Florida