“If women fought so hard to vote…did their daughters fight, too?”

This question resonated in our minds as we approached the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment in the United States, as well as many other suffrage anniversaries. It seems that first wave feminism happened worldwide, at almost the same moment. (Though we would later find out – as we detail below – that this is a misconception.) So, a few years ago, we set out to find the young girls – those under age 21 – who were active in suffrage movements.

We found more than just biographies. There were photographs, memorabilia, and even marketing campaigns that document how young girls were active in – and used in – suffrage movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are girls still fighting for this right today. And there are scholars studying these girls and their impact, hoping to help us have a more intersectional, complete picture of what it meant to fight for suffrage as a young girl.

These are some of their stories. We hope they inspire you to continue the fight for equal rights…and to keep uncovering the stories of girls.

Suffragist or Suffragette?

The words “suffragist” and “suffragette” look as though they could mean the same thing. Yet, each word has a very different meaning.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary online, “suffrage” means “the right to vote in an election”. The definition is rather broad considering the word is often used when talking about women and their struggle for the right to vote. Yet, the term can refer to other suffrage movements. In fact, use of the word “suffrage” first appeared in the United States during the early 19th century, and was initially linked to voting rights for free African Americans. A suffragist, then, is someone who is part of a movement that aims to gain the right to vote.

…courage calls to courage everywhere, and its voice cannot be denied.

Suffragist

The suffragist movement started campaigning many years before the suffragettes took over the scene. Local societies and small suffragist groups appear as early as the mid-1800s and many adopted a peaceful, constitutional, and non-violent approach to achieve their aims.

In the United States, the drafting of the “Declaration of Sentiments” in 1848 was led by a group of five women, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. The “Declaration” was presented at the 1848 women’s rights meeting in Seneca Falls. Though some of the over 100 attendees did not approve of women gaining suffrage, the majority voted to approve teh Declaration.

In the United Kingdom, these local societies and groups came together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) in 1897, which was led by Millicent Fawcett. They adopted the green, white, and red colors for their Give Women Rights campaign. Members of the early suffragist movements looked to argument and education for success. They held public meetings, handed out pamphlets, organized marches and parades, lobbied MPs, and wrote petitions that helped to increase their support in government over a period of many years.

Suffragette

Yet, by the early 1900s, some women believed a more direct and extreme approach was needed to demand the right to vote. Words were, quite simply, not enough. They broke away from the suffragist movement to become what the Daily Mail journalist, Charles E Hands, called a “suffragette.” The label was initially used to mock and belittle women fighting for the right to vote. Some, like the UK suffragettes, embraced the term; but others (such as the US suffragists) found the word offensive.

The following years saw militant suffragettes disrupt meetings, vandalize art and buildings, and many were often arrested for their behavior or actions. Mary Richardson, for instance, famously became known as the “slasher” after attacking a painting at the National Gallery in London with a meat cleaver, and the exiled Sikh Princess Sophia Duleep Singh threw herself in front of Prime Minister Asquith’s car. Another suffragist, Mary Leigh, was arrested in 1912 for throwing an axe-like weapon at the British Prime Minister.

As time went on, militant suffragettes carried out bomb attacks on public buildings; sent letter bombs; burned homes, churches, restaurants, and railways; cut phone lines; chained themselves to railings in protest; and spat at police or politicians. The inevitable arrests led to a new tactic – hunger strikes – which made way for brutal force-feedings by authorities. In 1913, the United Kingdom passed “The Cat and Mouse Act” that permitted the early release of women who had become so ill and weak as a result of their hunger strike they were often at risk of death. These women could then be re-arrested when they had recovered enough to continue their sentence.

Through their courageous actions, the suffragettes increased the profile of, and re-energized, the suffrage cause for women. However, the militant campaign was criticized by many in society, and in the United Kingdom, the Suffragettes would only be active for 10 years after their split from the Suffragists in 1903.

Together Now

The suffrage movement continued during World War I. Though some suffrage supporters halted their efforts to focus on the war effort, others continued the fight for women’s right to vote.

Many countries debated suffrage during the war. In 1915, several countries participated in the Congress of Women in the Netherlands, which argued for an end to the war and peace in Europe. One of the principles outlined for peace as the enfranchisement of women, which stated, “Since the combined influence of the women of all countries is one of the strongest forces for the prevention of war…this International Congress of Women demands their political enfranchisement.”

In the United Kingdom, nearly two million women joined the workforce during World War I. They both bolstered the war effort and filled in jobs left by men who went to fight. The effect was a drastic increase in the percentage of women employed, from 24% in July 1914 to 37% in November 1918. Some scholars believe that women’s increased presence in the workforce – and the armed forces – helped change perceptions of women’s ability to participate in political life.

In the United States, suffragettes remained more active. By the time the war had started, eight states had granted women’s suffrage. As in Britain, women took up traditionally male jobs, with their contributions enabling the war effort and bolstering perceptions of women in favor of suffrage. Seeking a Constitional amendment, women protested in front of the White House gates in 1917. The protest lasted nine months – from February to November – and resutled in many women being arrested and jailed. In prison, the women were treated brutally – and word of their treatment, including forced feeding, sparked outrage and strengthened public opinion in favor of suffrage.

Whatever their methods, the combined actions of suffragettes and suffragists around the world changed the political landscape of the late 19th and early 20th century. As the next section details, women’s suffrage was granted sporadically around the world – both in terms of the countries which enacted it, and in terms of which women were granted the right to vote.

“Suffragist or Suffragette?” written by Claire Amundson, Curator. Special thanks to Christina Wolbrecht, Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, for her advice and expertise.

When Did Suffrage Happen?

Our Thoughts

European colonization and imperialism repositioned women’s rights across the world and placed them below men on the social hierarchy. Women and girls protested, petitioned, and fought for decades to gain their rights, including the right to vote. The history of women’s suffrage is unique to each country, but there are some general trends in when women won their right to vote.

After World War I (WWI) and World War II (WWII) many countries legally provided women the right to vote. Similarly, during the 1960s and 1970s, as women’s liberation movements reemphasized women’s rights globally. Additionally, indigenous and Afro-descendants’ rights movements provided enfranchisement for Women of Color, including for African American women in the Southern United States and First Nation’s women in Canada.

At the beginning of the 21st century, women in many conservative countries in Southwest Asia won the right to vote. To date, the Vatican, the capital of the Roman Catholic Church, is the only country that does not allow women to vote. Cardinals, who must be men, are the only ones allowed to vote in papal elections.

Marketing Young Suffrage

Girls did not only participate in the suffrage movement; they were also one of its most utilized marketing images. In particular, activists in the United States and United Kingdom frequently utilized the image of girls in advertisements, fliers, postcards, and even political cartoons to discuss and promote suffrage. Below are just a few examples of how girls were utilized to advance the suffrage movement.

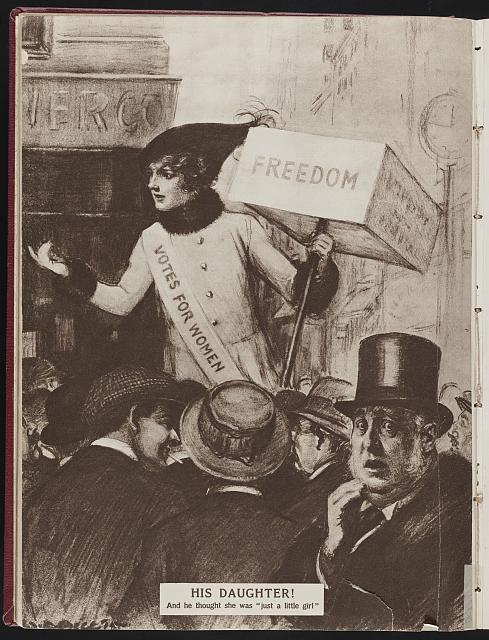

“His daughter! And he thought she was ‘just a little girl'” cartoon by W. E. Hill, February 20, 1915. Courtesy Library of Congress

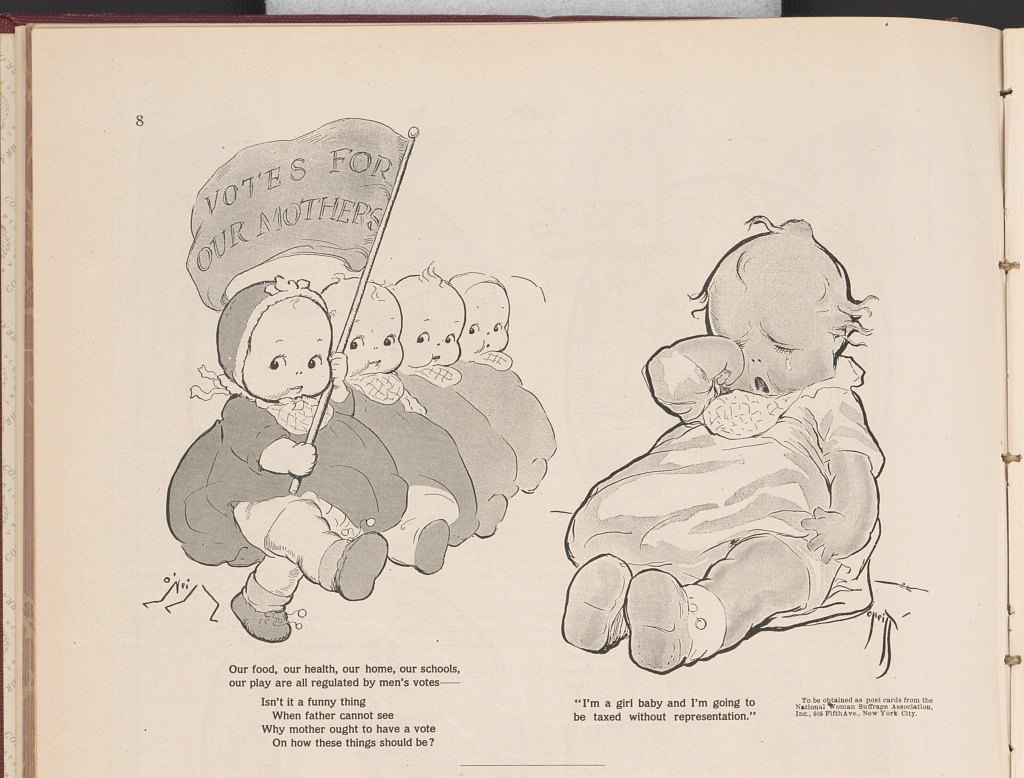

“Suffrage kewpies” by Rose Cecil O’Neill, published February 15, 1920. Courtesy Library of Congress.

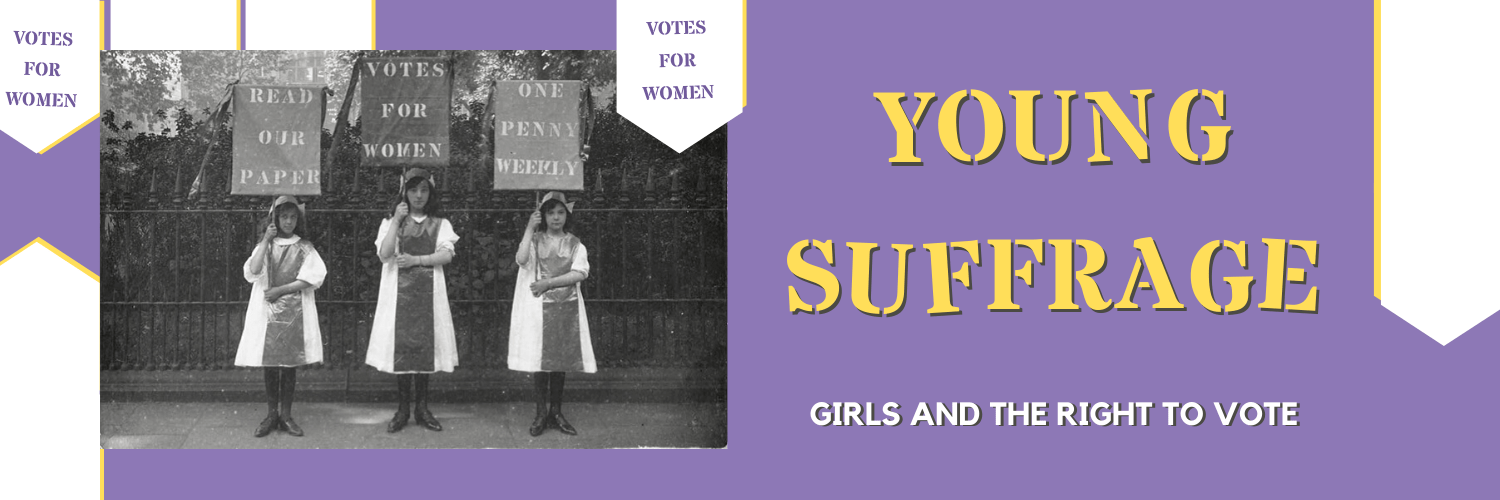

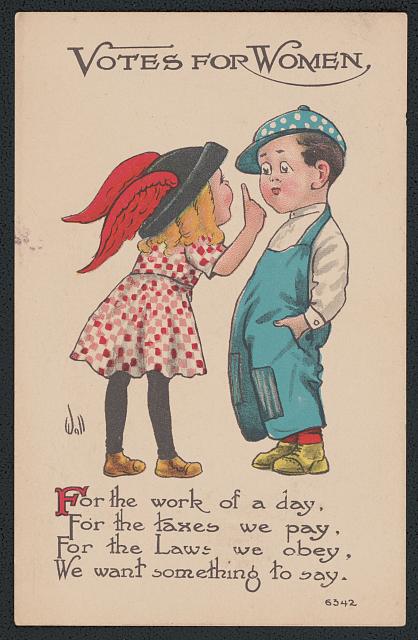

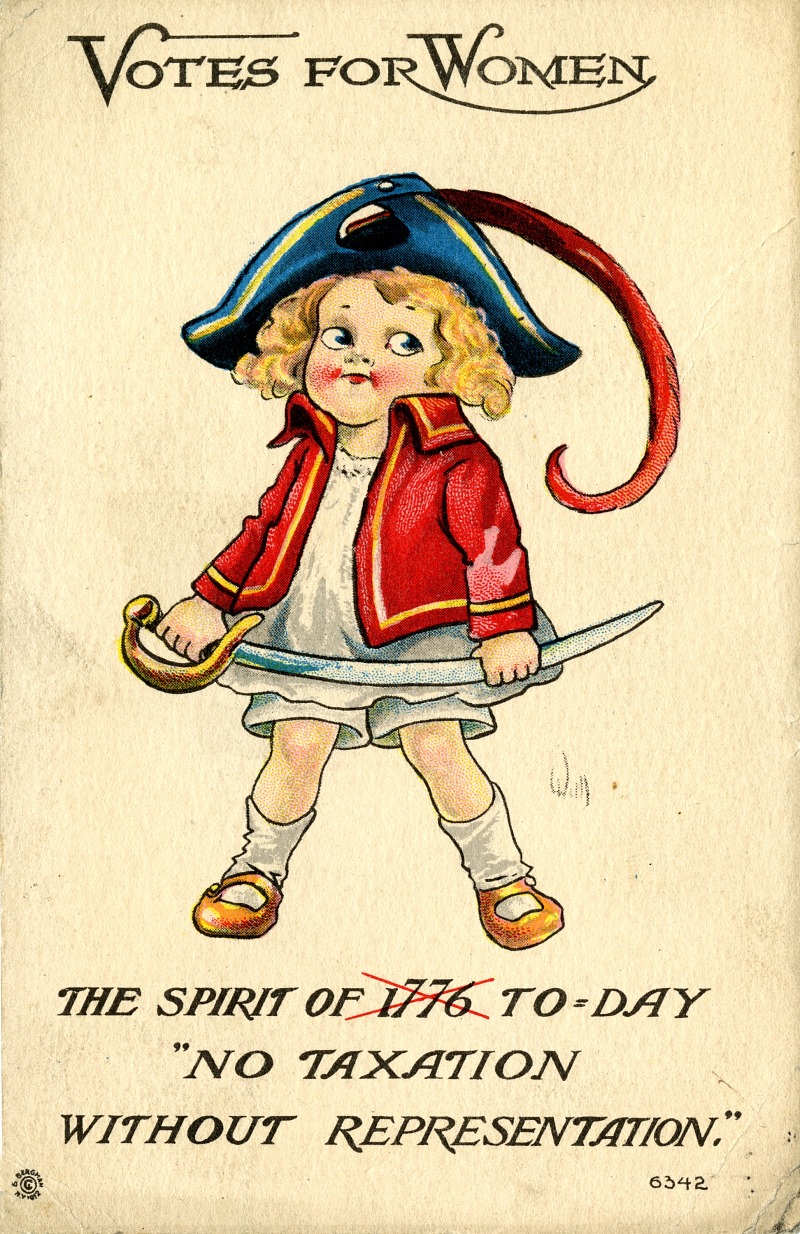

“Votes for Women,” circa 1913. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Commercial picture postcard published as part of the Woman Suffrage Series by ETW Dennis & Sons, Limited, Scarborough in 1907. This postcard captioned ‘Fellow Women, Our Day Dawns At Last’ features the child in spectacles adopting the pose of a public speaker, a copy of the Daily Mail on the table before her.

The postcard was sent from M.F. to Miss Dorothy Pethick in December 1907 whilst she was staying in Rome. Dorothy Pethick was the sister of the Suffragette leader Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence.

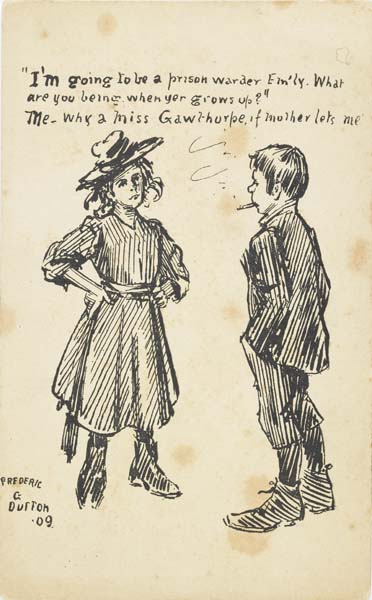

“I’m going to be a prison warder, Em’ly” published c. 1909 by National Women’s Social and Political Union. The postcard designed by Frederic Dutton depicts a young girl with aspirations of becoming a suffragette leader similar to Mary Gawthorpe. The sale of popular, comic postcards raised funds for the campaign and helped to spread the Votes for Women message by ridiculing the anti-suffrage argument and the injustice of the voting system. Courtesy Museum of London.

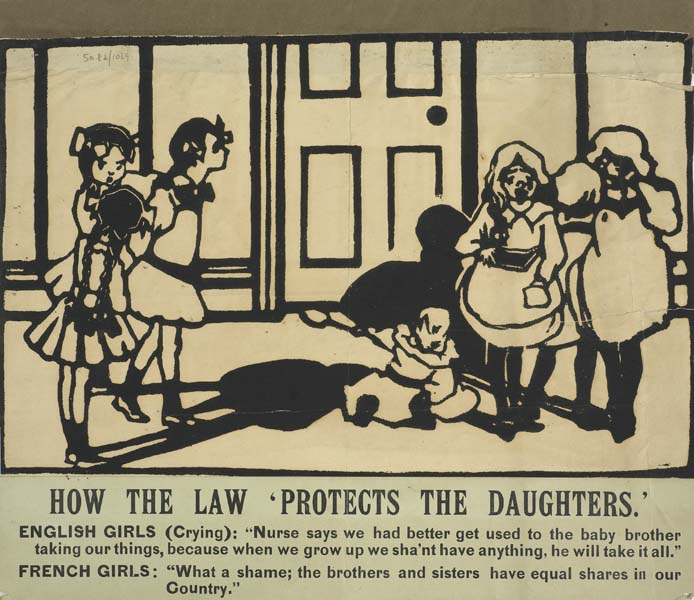

Pro-Female Suffrage propaganda poster, ‘How the Law Protects the Daughters’. One in a series of 6 posters designed by ‘Mac’ for the Suffrage Atelier highlighting legal discrimination against women. The Atelier artists specialised in hand-made wooden block prints, stencilling and etchings and produced visually powerful posters and postcards to publicise the pro-suffrage campaign. Courtesy Museum of London.

Postcard, “To My Valentine: Love Me Love My Vote”. Published February 12, 1921. Courtesy National Museum of American History.

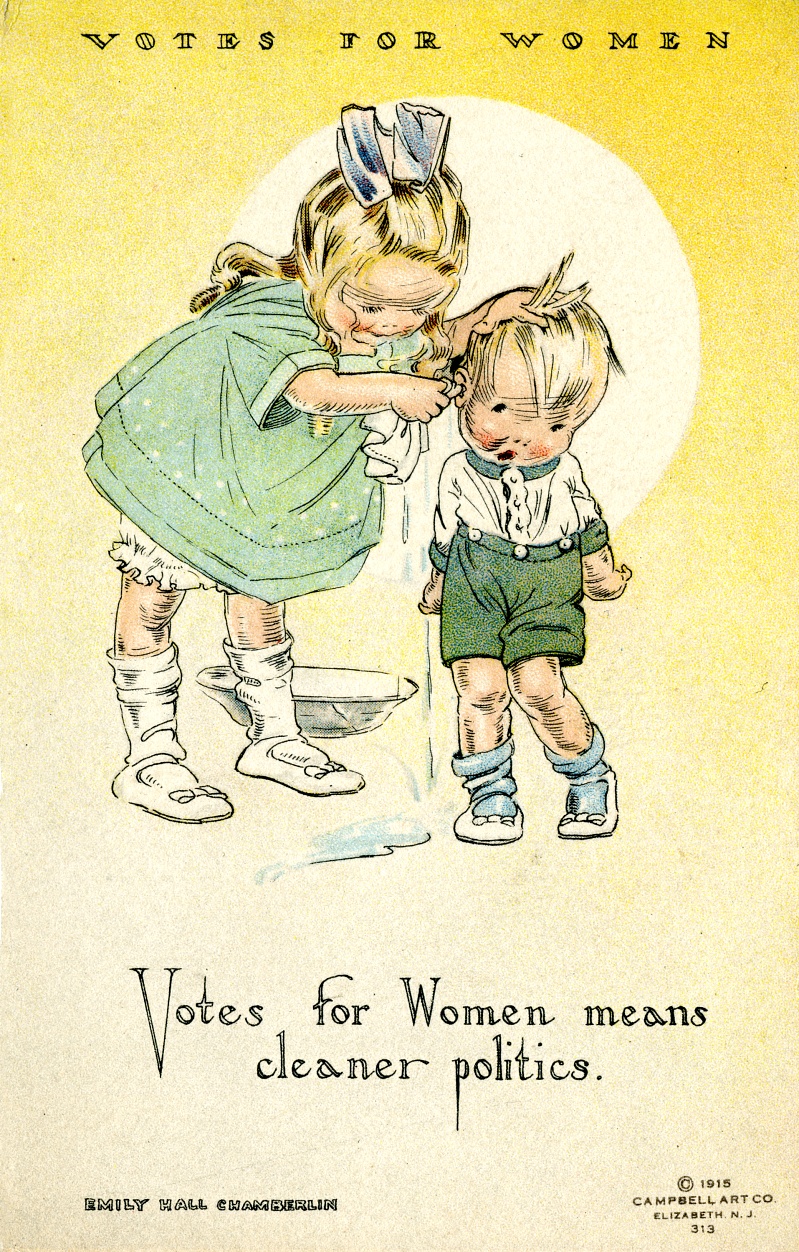

Women countered the argument that they were too pure for the dirty business of politics by invoking the Progressive Era’s belief in “social housekeeping.” The logical extension of women’s ability to clean and order their homes was to apply those skills to clean and remedy the ills of society. Some postcards used images of children to project a nonthreatening image of women voters.The postcard was part of a 1911 campaign for suffrage in California, which by a state-wide referendum in that year became the sixth state to approve woman’s suffrage. Courtesy National Museum of American History.

Invoking the American Revolution through the slogan, “No Taxation without Representation,” the postcard argues that America is now doing the same thing that it rebelled against by denying representation through voting to tax-paying women.The National American Woman Suffrage Association began a postcard campaign in 1910, partly to raise awareness of the cause and partly as a fundraiser. The cards could be funny, serious, or sentimental. Some employed powerful patriotic symbols and logical arguments to make their case for woman’s right to vote. Courtesy National Museum of American History.

The Allender Girl

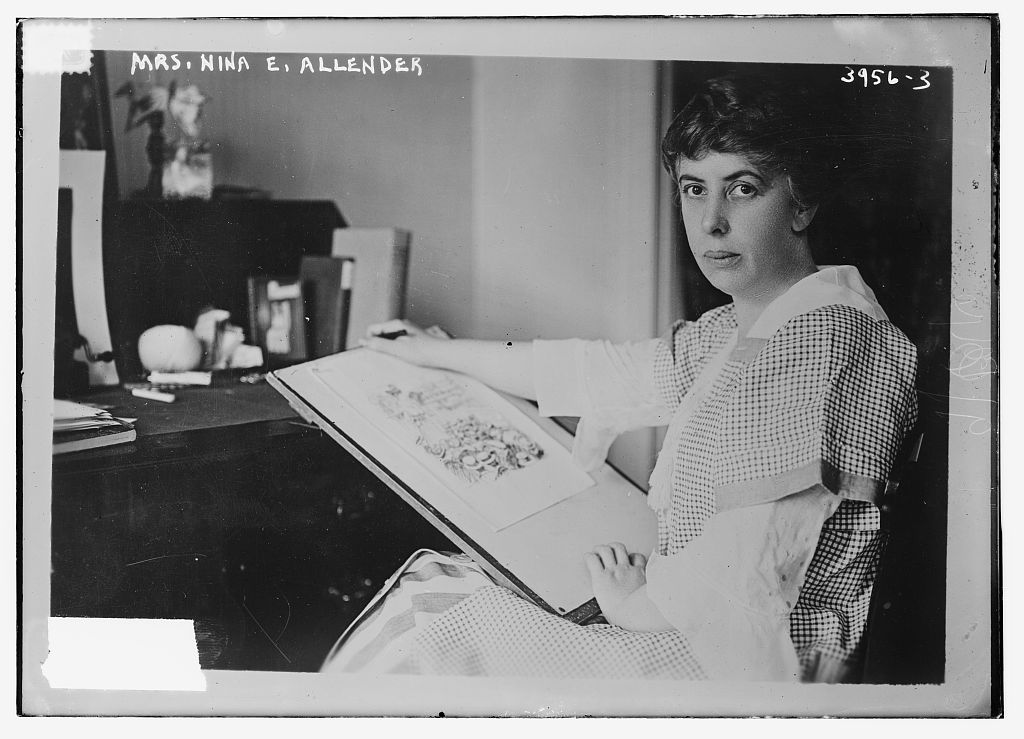

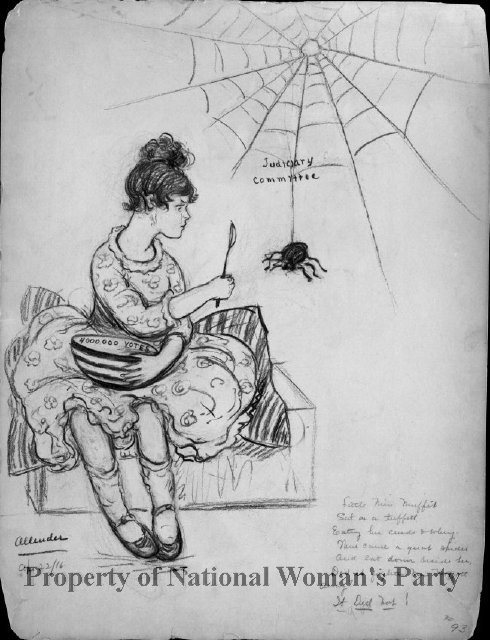

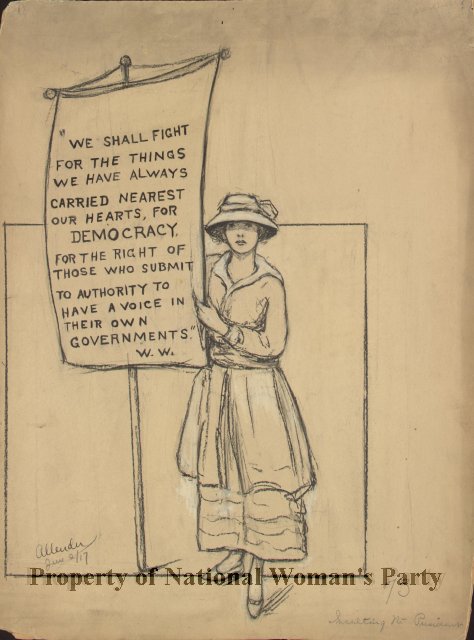

One nationally known and exhibited suffrage activist was Nina E. Allender. Born in Kansas in 1873, Nina was the daughter of two teachers. By age 8, her parents transitioned to working in the government, and the family moved to Washington, D.C. She seems to have had a largely typical life for a middle class girl: she married at 19, but within a decade divorced her husband after he ran off with another woman. She enrolled in classes at the Corcoran Museum of Art, then in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, to learn painting. Though she exhibited her work, it wasn’t until Nina was 38 and involved in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) that her work gained prominence. During their 1912 pageant in Washington, she became chair of “posters, post cards and colors,” quickly becoming president of the D.C. chapter and, by 1913, illustrator of The Suffragist.

Nina published her first political cartoon on June 6, 1914, featuring what would become her signature “Allender girl”: a young, stylish, attractive, and highly capable American woman. It was the first time suffragists had been portrayed as such, and was influential in shaping public image of what a woman’s rights advocate was like. Nina went on to produce nearly 200 political cartoons for The Suffragist and its successor, Equal Rights, most of which featured the Allender girl.

Mrs. Nina E. Allender at work, circa 1915-1920. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Nina E. Allender’s cartoons are now in the art archives of the Library of Congress. Her drawing of Susan B. Anthony mounting the steps of the Capitol with a petition of 20,000 names asking for the vote for women) to present to Congress was made into a postage stamp in 1936, in commemoration of the thirtieth anniversary of her death. Many of her original cartoons are also held at The Sewell-Belmont House in Washington DC.

For a more in-depth look at Nina’s work, visit the National Women’s Party exhibit, “A Woman Speaking to Women” here.

Profiles in Courage

What would a young suffragist or suffragette say? Who were the girls participating in suffrage movements?

Our team researched girls – under age 21 – from across the world who fought for their right to vote. Below are their stories and postcards we believe they would have written. Do you agree with our imaginings? What other girls do you know who fought for suffrage?

Read the postcard

Emmeline Pankhurst

April 1868

My Dear Friend,

I do hope this letter finds you well. I must apologize for not writing sooner, I have been quite preoccupied as of late. I recently saw Lydia Becker, editor of Women’s Suffrage Journal speak at a meeting here in Manchester. Mother did not think it appropriate for a 14-year-old girl to attend the meeting, but I insisted when I learned that Becker would be in attendance. Mother could not convince me otherwise and quickly gave into my demand. She knows how I adore reading Becker’s work in her Journal. While I have been fond of the Journal for quite some time, it was not until after Becker’s address on women’s voting rights that I can claim to be a conscious suffragist. Have you been attending meetings near you?

Sincerely,

Emmeline

1858 – 1929

Born into a family of social activists, Emmeline became a suffragette at age 14. She founded the Women’s Franchise League and, later, the Women’s Social and Political Union. She was also active in supporting Britain during World War I and in the first for labor reform.

Read the postcard

Elisabeth Dmitrieff

April 11, 1871

I hope this postcard finds you well as I write to you with amazing news! Today, Nathalie Lemel and I have succeeded in founding the Women’s Union for the Defence of Paris! I had no idea what I would achieve when Karl sent me to cover the Paris Commune last month, but I knew I had to fight.

We had our first meeting of the union today in which we elected a central committee and I am to be the general secretary. These working class women of the union are truly remarkable and I believe that we will make great strides towards emancipating ourselves and eventually getting the vote! Heres to the future!

Yours,

Elisabeth

1851 – 1910

Born in Russia, Elisabeth is commemorated in the Elisabeth Dmitrieff Square. The work of the Women’s Union for the Defence of Paris paved the way for feminist movements of the twentieth century that eventually led to the granting of the right to vote for women in France in 1944.

Read the postcard

Meri Mangakāhia

1893

Kia ora (hello) e hoa (friend),

I hope this letter finds you well! I have recently become quite occupied with the suffrage movements. Although we have had the right to vote for local government since 1876, I find it frustrating that we are not allowed to vote for members of the New Zealand House of Representatives.

More frustratingly we are not allowed to vote for the Te Kotahitanga- our own parliament and we can’t even participate in it! Māori women have always had rights, but under the Colonial laws we lost them and now Māori parliament won’t let us participate politically either! Hāmiora and I hope to challenge this with his involvement in Te Kotahitanga.

Whakaponokore,

Meri

1868 – 1920

A Māori suffragette in New Zealand, Meri became the first woman to address the Te Kotahitanga Parliament in 1893, at age 25. She argued for women’s representation in government, which resulted in the 1897 passage of laws granting women the right to vote.

Read the postcard

Pura Villanueva Kalwa

ca. 1906

Today was our first meeting at Asociacion Femiista Ilongga. It is a dream to see my group commence, and for us to affirm our fight to win the vote. The ladies are all so very smart, and it gives me great confidence and joy to see us bond over our fight.

Gone are the days of being a beauty queen, and here are the days of being a queen in the fight for our rights! The next time they parade and photograph me, it will be with the banner of victory rather than a crown.

It is a hard fight, but well worth it. I know that my work here, and as an editor for El Tiempo, will not be in vain. They must give us our rights, not just our right to vote. And I will not stop until we have it.

– Pura

1886 -1954

Born in the Philippines, Pura organized the Asociacion Feminista Ilongga, a suffrage group, at the age of 20. She achieved her dream at age 51, leading the vote that passed the first legal rights for women in the Philippines.

Read the postcard

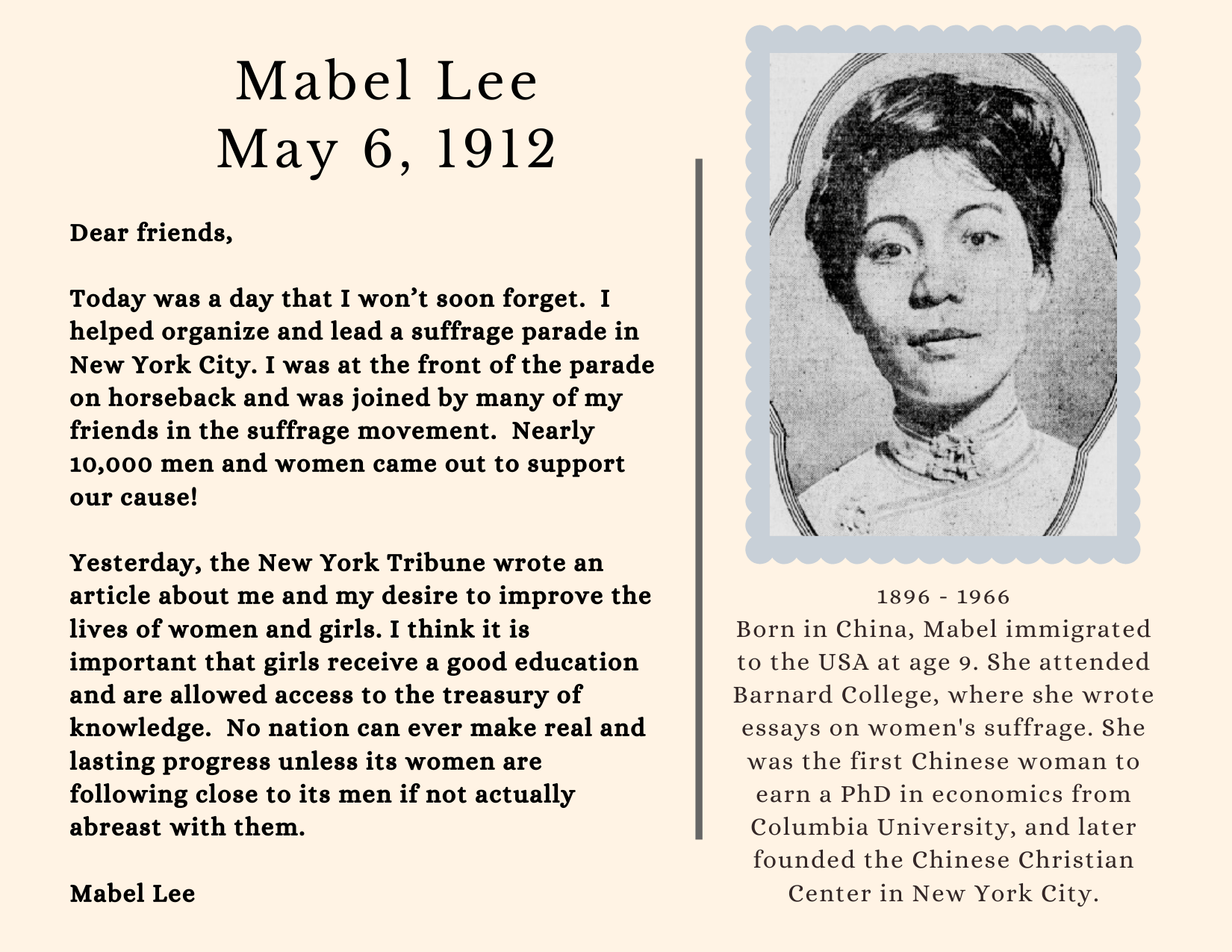

Mabel Lee

May 6, 1912

Dear friends,

Today was a day that I won’t soon forget. I helped organize and lead a suffrage parade in New York City. I was at the front of the parade on horseback and was joined by many of my friends in the suffrage movement. Nearly 10,000 men and women came out to support our cause!

Yesterday, the New York Tribune wrote an article about me and my desire to improve the lives of women and girls. I think it is important that girls receive a good education and are allowed access to the treasury of knowledge. No nation can ever make real and lasting progress unless its women are following close to its men if not actually abreast with them.

Mabel Lee

1896 – 1966

Born in China, Mabel immigrated to the USA at age 9. She attended Barnard College, where she wrote essays on women’s suffrage. She was the first Chinese woman to earn a PhD in economics from Columbia University, and later founded the Chinese Christian Center in New York City.

Read the postcard

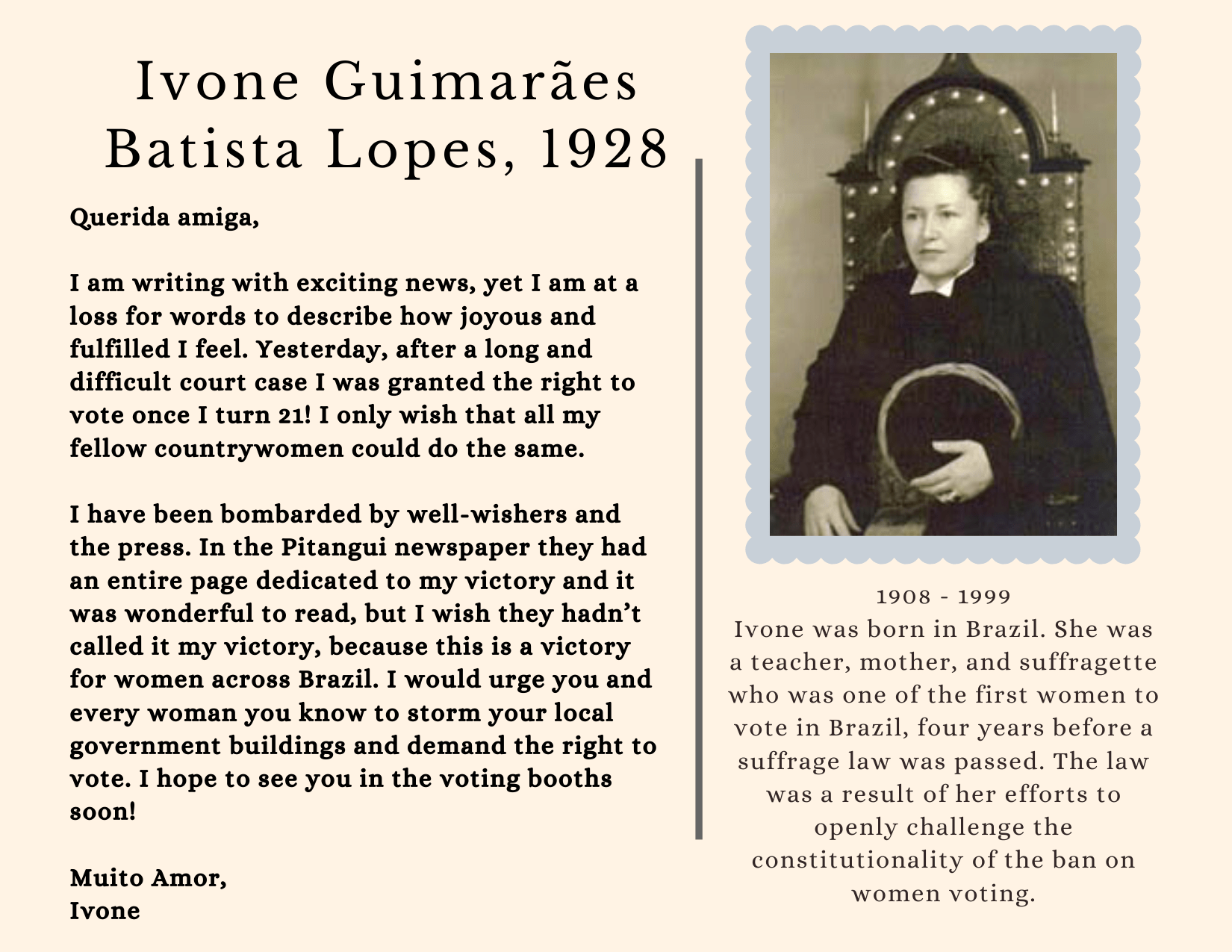

Ivone Guimarães Batista Lopes, 1928

Querida amiga,

I am writing with exciting news, yet I am at a loss for words to describe how joyous and fulfilled I feel. Yesterday, after a long and difficult court case I was granted the right to vote once I turn 21! I only wish that all my fellow countrywomen could do the same.

I have been bombarded by well-wishers and the press. In the Pitangui newspaper they had an entire page dedicated to my victory and it was wonderful to read, but I wish they hadn’t called it my victory, because this is a victory for women across Brazil. I would urge you and every woman you know to storm your local government buildings and demand the right to vote. I hope to see you in the voting booths soon!

Muito Amor,

Ivone

1908 – 1999

Ivone was born in Brazil. She was a teacher, mother, and suffragette who was one of the first women to vote in Brazil, four years before a suffrage law was passed. The law was a result of her efforts to openly challenge the constitutionality of the ban on women voting.

Studying Suffrage

What’s it like to study girls who fought for their rights? How do scholars find out about these girls, and what can they tell us about women’s suffrage? We asked scholars from a variety of fields to help us answer these questions and talk about their work.

Studying Suffrage: Allison K. Lange

In conjunction with our Young Suffrage exhibition, we would like to share a series of interviews with academics who are studying suffrage around the world.

Studying Suffrage: Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

In conjunction with our Young Suffrage exhibition, we would like to share a series of interviews with academics who are studying suffrage around the world.

Studying Suffrage: April Young Bennett

In conjunction with our Young Suffrage exhibition, we would like to share a series of interviews with academics who are studying suffrage around the world.

GirlSpeak – Young Suffrage

(July 2018)

GirlSpeak – Mothers, Daughters, and Suffrage

(March 2020)

More than Voting: From Suffrage to the Women’s March

Young people have been on the front lines of recent protest and civil rights movements—from March for Our Lives to climate strikes. While their activism is particularly visible in these recent movements, their involvement is of course nothing new. Young people, and girls in particular, have had an important role in social movements throughout history, from suffrage to the Women’s March. However, when one thinks about the suffrage movement, the images that immediately come to mind are those of adults and older women in particular, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. The relative lack of visibility of girls in the suffrage and women’s rights movement raises many questions about their role and place in these movements: Do women’s movements accurately include girls as “girls,” or are they merely “little women” who will be given their rights upon reaching legal age requirements? To what extent are women’s movements “girl movements”? Was their presence in the suffrage movement merely symbolic? Were girls peripheral figures or equal partners in the suffrage movement?

The suffrage movement was varied and complex, and none of these questions can be easily answered. On the one hand, many suffragists encouraged girls to participate in the movement. British suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst created the organization, Junior Suffragettes, as a means to facilitate girls’ participation in the movement. The impetus for activism can be found in the girlhood of many suffragists. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote about how experiences during girlhood drew attention to gender disparities and were formative to their later activism. Suffragists did not confine their activism to women getting the right to vote but were involved in wide-ranging reforms that focused on improving the conditions of girls’ lives, from ending child labor to expanding education. These broader efforts suggest that suffragists recognized that these issues related to girlhood could not be disentangled from their efforts to gain a greater political voice and challenge the underlying injustices that relegated women to the margins of political life.

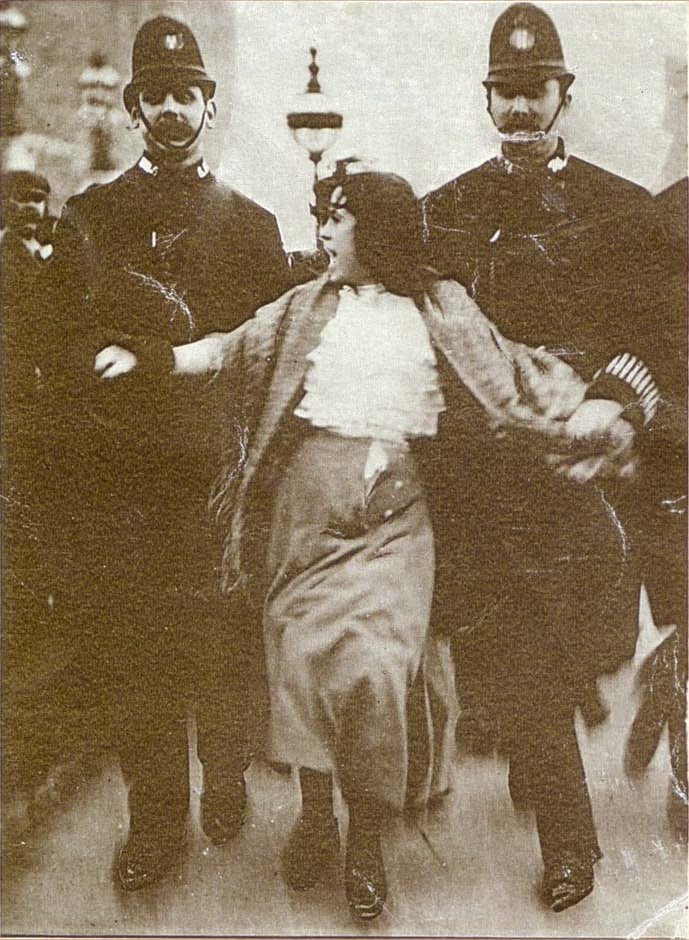

Dora Thewlis under arrest, 1907. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Junior Suffragettes Club in Victoria Park. Image courtesy Roman Road London.

Although this evidence suggests girls were not merely symbolic and peripheral figures in the suffrage movement, some suffragists did have an uneasy relationship with girls, which can be attributed in part to the negative connotations often associated with the term “girl.” Suffragists worked to prove that they were mature and responsible citizens, which meant distancing themselves from the immaturity and dependence that seemingly defined girlhood. In a speech on “The Pleasures of Age,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton declared that “fifty not fifteen is the heyday of woman’s life.” Stanton and other suffragists used age and its associations with wisdom and maturity to vindicate women’s involvement in political affairs.

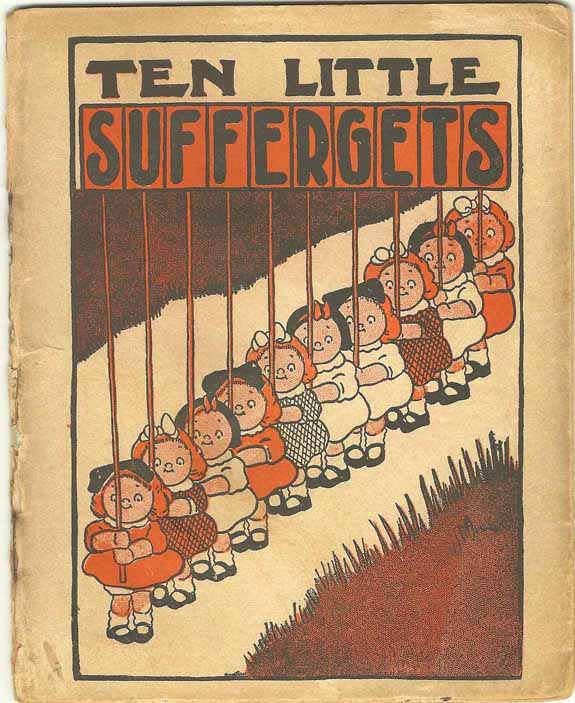

Some suffragists also opposed girls’ involvement, viewing it as doing more harm than good to the movement. Young suffragists, from Elsie Duvall to Dora Thewlis, were dismissed disparagingly as “baby suffragettes” and “silly little girls.” Anti-suffragists viewed the involvement of girls as a sign of weakness and used it to criticize the movement. The children’s book, Ten Little Suffergets, published in the early twentieth century, provides just one example of how the image of girls and “baby suffragists” was used to undermine the movement. Girls like Elsie and Dora were viewed as incapable of rational thought and acting on their own accord and viewed simply as pawns controlled by adults. Of course, these discourses are not confined to history. Child rights activists Malala Yousafzai has been accused of being part of a conspiracy orchestrated by the West in her efforts to promote the rights of girls and women. Similarly, many, including Russian president Vladimir Putin, painted climate activist Greta Thunberg as manipulated by others to serve their interests, accusing her of not being able to understand the complex global issues surrounding climate change.

What emerges then is a complex and sometimes paradoxical view of girls’ role in the suffrage movement. While some within and outside of the suffrage movement readily dismissed girls’ involvement, other suffragists recognized that girls and issues related to girlhood were integral to suffrage and female empowerment. This exhibit on “Young Suffrage” illustrates that suffrage activism cannot be thought of as simply an adult phenomenon. Girls participated in the suffrage movement in a variety of ways, and along with their adult counterparts, girls risked violence and imprisonment to advocate for the right to vote. Although their participation may still be overlooked, girls persevere, fighting against “silly” stereotypes and continuing to effect social and political change.

Essay by Elizabeth Dillenburg, Resident Scholar

“Booklet : Ten little suffergets. [Circa 1910-1915],” Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection, accessed March 17, 2020

A Girl's Guide to Her Rights

Girls’s rights are human rights. Yet millions of girls continue to struggle to claim them. This guide is based on the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child, which guarantees the rights of all children.

Exploring Suffrage Educational Guide

This PDF guide is filled with activities to help you explore the exhibition’s theme – girls in suffrage movements – and discover the different types of historical sources used by museums, archives, and historians to uncover the past.

Credits

This exhibition was produced by Tiffany Rhoades Isselhardt, Elizabeth Dillenburg, Sage Daugherty, Claire Amundsen, Maria Smith, and Louisa Yorke.

Special thanks to the National Woman’s Party and Library of Congress for their images, and to all the scholars who continue to work on suffrage and women’s rights scholarship.

Title image for banner provided by Museum of London. “Suffragette poster parade” by H. Searjeant, 1911. Poster parade of young suffragettes advertising Votes for Women, the weekly newspaper of the Women’s Social and Political Union. The young Suffragettes were taking part in the Coronation Procession of 1911 as part of the Votes for Women newspaper contingent.

Resources

US National Archives – Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment

Teach a Girl to Lead Lesson Module: Women’s Suffrage in the United States

Black Women & The Suffrage Movement: 1848 to 1923

Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia (virtual exhibition)

How Women Won the Vote: Teaching Guide

Books on Suffrage – Recommendations from A Mighty Girl

Abolitionist and Reformer Lucretia Mott’s Story

Centuries of Citizenship Map: States Grant Women the Right to Vote

Timeline: The Official Susan B. Anthony Museum & House

The Equality State and Wyoming’s Trailblazing Women: Wyoming Women’s Suffrage

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Children, Life, and Contributions

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Biography, Significance, Seneca Falls, Books, and Facts

Susan B. Anthony, Icon of the Women’s Suffrage Movement

Wyoming Grants Women the Right to Vote

Which State Had Women’s Suffrage First?

First to Vote: Women’s Suffrage in Wyoming

Suffrage and Women: How it Happened

Wyoming and the 19th Amendment

Women Have Been Voting in Wyoming for 150 Years, and Here Is How the State Is Celebrating

Women of the Century in Wyoming: Ten Influential Females in State History

Women’s Suffrage in the Wild West

Who Was Elizabeth Cady Stanton?

Women’s Suffrage and Women’s Rights

Wyoming Almost Repealed Suffrage for Women

Not All Women Gained the Vote in 1920

When Did Black Women Get the Right to Vote?