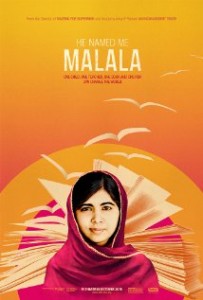

I’m slightly ashamed to admit I didn’t know all that much about Malala Yousafzai before I saw Davis Guggenheim’s latest venture (director of An Inconvenient Truth). I’d heard Malala’s story when it had been in the news some years ago, and once I had made the connection between my vague memory of the events and the film my friend was suggesting we watched, I was more than keen to tag along.

I’m slightly ashamed to admit I didn’t know all that much about Malala Yousafzai before I saw Davis Guggenheim’s latest venture (director of An Inconvenient Truth). I’d heard Malala’s story when it had been in the news some years ago, and once I had made the connection between my vague memory of the events and the film my friend was suggesting we watched, I was more than keen to tag along.

For those out there who may still be uncertain as to who she is – Malala is a Pakistani activist still in her teens, who was targeted and shot by the Taliban in an attempt to stem her vocal support for female education. Surviving the near-fatal injury to her head, Malala has subsequently received the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize, making her the youngest recipient ever at the ripe old age of 17. Most recently she has opened a school for Syrian refugees in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon and acts as a spokesperson for underprivileged children the world over. So, a pretty cool girl all things considered – however she’s received more criticism than perhaps you’d imagine; accused of promoting Western agendas and providing the perfect opportunity for “the white man to relieve his burden and save the native” (this quote coming from freelance journalist Assed Baig).

The documentary could in some ways be seen as dispelling many of the criticisms raised against Malala and her family, through attempting to provide an honest depiction of her and her goals.

A minor criticism my friend raised once we had left the cinema was the use of animation for some parts of the narrative. Though it was beautifully done, and from a cinematic point of view a good way to break up the film’s predominant interview-style, I suppose it could be said to slightly romanticize Malala’s homeland of Swat and its inhabitants – presented as they were as living in a kind of rural idyll. However, I thought it was perhaps also an attempt to show the Islamic states as something more than a site of religious extremism. It is a common problem with Western representations of the Middle East in that they tend to swing between exoticism or violent extremism, both as dehumanizing as the other. However, it seemed to me that the film was attempting to show us Malala’s home as she sees it, as a place of love, peace and beauty, rather than allowing it to be shown as a backwards and repressive environment.

It can be difficult to strike a balance in the representation of the Middle East. She never presents Britain or the US as superior to her own country, and it is not as if moving from her home has solved all of her problems. Indeed, I think it’s an important subtext of the film that we in the west don’t grow complacent in the knowledge that we are fortunate enough to have gender equality in education and freedom of speech, and forget that there are still those who do not. Her story is a success, not because she can now carry out her activism from the comfort of a liberal, democratic society, but because she remains loyal to her home and hopeful for its future. Her harrowing and extraordinary experience has not made her hateful to those who injured her, or dismissive of her society, but sparked a desire in her to see it changed.

Reading some reviews of the film, I was surprised to see so many people turning their criticism on Malala’s father, Zia. A teacher himself, he is a vocal advocate of education for all children, boys and girls, and as such some have said he enforced his ideals onto Malala, using her as a kind of mouthpiece and consequentially exposing her to the threat of the Taliban. With the story written down on paper, I suppose the cynics among us could easily take this stance, partially because it seems unbelievable that a girl so young could have such bravery in her opinions. However, it seems to me it would be a difficult idea to maintain when faced with the portrait of Malala and her family as shown in the film. It is clear that each have their own personalities that are allowed to thrive regardless of any notions of gendered hierarchy and there is such genuine love between all members it seems absurd to suggest Zia would use his daughter for some kind of political gain.

It may well be that Zia’s ideals influenced Malala’s actions, but they are ideals that promote freedom of speech and the right to education. As Malala herself points out, if it were not for her father’s encouragement, she may have been able to remain in her beloved Swat valley but she would be uneducated with several children, bound to her house and husband. It is surely better to instill your children with an independent mind and the bravery to express it than to remain under oppressive forces simply to avoid conflict. In a society based on traditional and patriarchal values, Zia himself cuts an impressive figure in his comparatively progressive support of equality and freedom of speech. It therefore seems slightly ridiculous that someone who would be considered radically open minded in his own society is still accused of putting too much pressure on his daughter by western critics. This is perhaps due to the unfair stereotype of oppressive Islamic families, which this film helps to subvert. Merely observing the fond father-daughter relationship was enough to make the film moving and engaging, but it also allows us to see Malala for what she really is: a teenage girl who struggles with homework and making friends, yet one who is also capable of exciting great change and debate.

It is a great film, worthy of attention and praise and important to watch simply to have a better appreciation of Malala as a person, not just a news story. In her humor, intelligence and bravery she is an important example of the possibilities of education, and the kind of person society would be denied if she were confined to the home, as so many young girls still are. She also serves to remind us that being small in number is no barrier on what can be achieved, and as she said herself, ‘one child, one teacher, one book and one pen, can change the world’.

-Scarlett Evans

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.