Some people believe Black girls have secret lives, separate from the versions of their lives governed by adults. They aren’t always secret, but sometimes they are sacred, especially when they create them with other Black girls.

In the seventh grade, my middle school best friend and I went to the libraries in our respective neighborhoods on a regular basis. We would bring our haul to school, read them on the school bus and throughout the day as we stole snatches of time in class, and trade them with one another when we were finished with them. Sometimes we read books written by adults, which were certainly intended for adult readers. Other times we read books from the YA section of the library. We weren’t picky readers, but many of the YA books were realistic fictional dramas, often written by Black women writers like ReShonda Tate Billingsley, Sharon G. Flake, Angela Johnson, Jacqueline Woodson, and Sharon Draper. School librarians and public librarians often warned young people that it was not good to share library books, but we trusted each other and never misplaced one another’s library books.

We were not the only girls who exchanged books. I was in middle school during the tail end of the Gossip Girl book series craze, and the beginning of the excitement about the Twilight series. The book exchanges made up clandestine spaces in which we read and thought about friendship, romance, death, sex, tragedy, injustice, and the confusing worlds that adult characters had fashioned for the teen protagonists and that real-life adults had fashioned for us. Sometimes the exchange itself was a manifestation of an ethic of care, and a way to communicate which topics and ideas were important enough to us to share them with our friends.

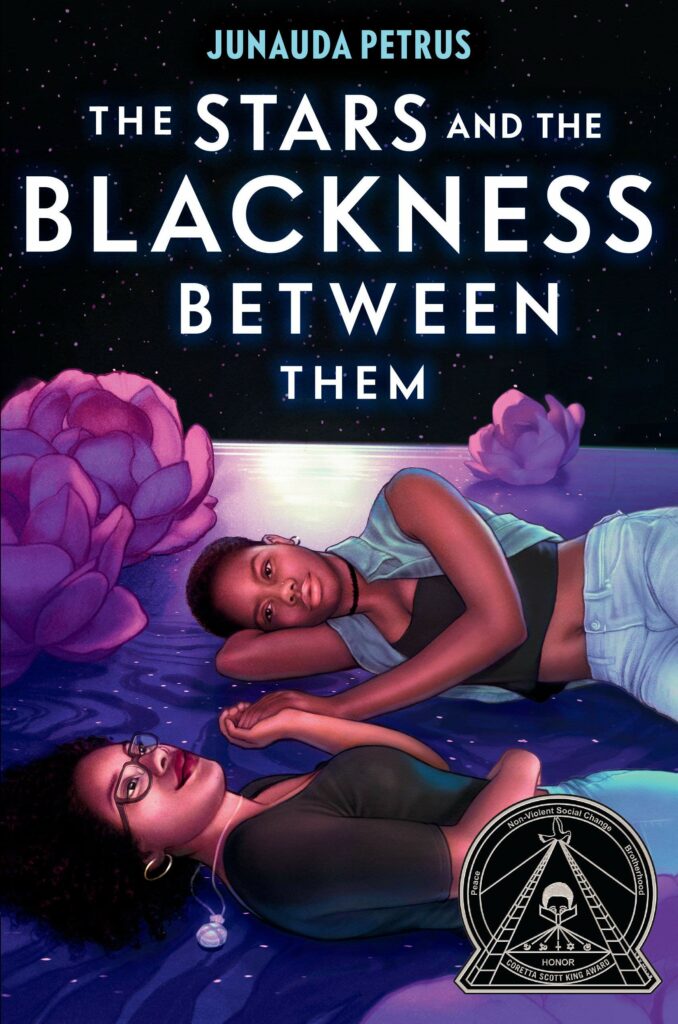

I have not stopped reading YA, though I don’t trade books with friends anymore. Reading YA still reminds me of the ethic of care and sharing as a cultural practice among some Black girls. I read The Stars and the Blackness Between Them (2019), a debut novel by Junauda Petrus, just after it was published almost a year ago. In this novel, sixteen-year-old Trinidadian Black girl Audre, named of course after Black feminist lesbian warrior poet Audre Lorde, is sent to live in Minnesota with her father after her mother learns of her romantic relationship with another girl. In Minnesota, she meets sixteen-year-old Mabel, who becomes terminally ill. Together, they teach each other to live in their truths. For Mabel, life is too short not to, and she is on a mission. For Audre, her ancestors visit her in her dreams and inspire her to follow her heart—to make friends in a new country, and to let go of the shame she holds due to her mother’s homophobia. Petrus joins a cadre of Black YA writers today who center Black characters who are allowed to be both vulnerable and vigorous. Despite her’ use of dated colloquialisms and misrepresentation of Black English (also known as African American Vernacular English) in the teens’ dialogues, the novel is dreamy, a page-turner, and centers the sacred friendships between teen Black girls. Mabel and Audre exchange dreams and the opportunity to care for one another the way my middle school best friend and I exchanged books—sometimes it was secret and against adults’ best advice, and sometimes it was sacred.

-Destiny Crockett

Guest Contributor

Originally from St. Louis, Missouri, Destiny Crockett (she/her) is a 3rd year doctoral student in the Department of English at the University of Pennsylvania. She studies Black feminist theory, 20th and 21st century African American women’s literature, cultural productions, and literary archives, as well as Black girlhood studies. Destiny earned her B.A. in English, with certificates in African American Studies and Gender and Sexuality Studies, from Princeton University in 2017.

I think Destiny is an amazing writer filling her writing with truth heart and promise