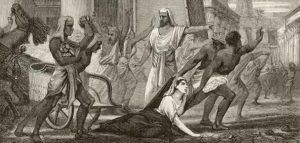

The murder of Hypatia. Photo Credit: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/hypatia-ancient-alexandrias-great-female-scholar-10942888/

In this column, I’ll be looking at an inspirational girl from every century, starting in the 21st century and working back to the 1st century CE. As a historian and feminist, I thought this was the perfect way to share the stories of awesome historical girls from around the globe. Hopefully you’ll learn about some girls you might not have otherwise heard about as these Trailblazers deserve to be your next role models!

My 4th century trailblazer Hypatia (c.370-415) was an Egyptian scholar and probably the earliest female mathematician of note in the world. Sadly, as appears to be the case whenever there is a gruesome murder involved, people seem more interested in Hypatia’s death than her life. Hopefully, this blog will demonstrate that Hypatia was a pretty incredible girl and deserves to be remembered not only as a person, but also as a feminist symbol.

Hypatia was born during a very turbulent era in Alexandria’s history. She was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, a prominent mathematician and astronomer and the last member of the Alexandrian Museum. The Alexandrian Museum was not a museum we would recognise though, it was actually a university and its collection of over half a million scrolls encompassed the infamous Library of Alexandria. Theon of Alexandria refused to raise Hypatia in a traditional manner (go Theon!) and instead raised her as many boys would have been raised at this time – by teaching her his trade. For Theon, this meant bringing Hypatia up as an academic. He taught Hypatia all about mathematics, astronomy and many other topics, no doubt inspiring her lifelong passion for learning. Hypatia went on to become a mathematician, astronomer and philosopher, just like her father, and was a respected academic at the Alexandrian Museum (a position which seems to have only been available to men before Hypatia came along). Hypatia chose never to marry, instead devoting herself to a life of learning and teaching.

Hypatia’s mind is surprisingly famous for someone whose works all perished, and her reputation precedes her even into the 21st century. We know that Hypatia wrote impressive works on astronomy and advanced geometry and algebra. Hypatia is credited with commentaries on Apollonius of Perga’s Conics (geometry) and Diophantus of Alexandria’s Arithmetic (number theory), as well as an astronomical table. In writing these commentaries, Hypatia continued to contribute to her father’s intellectual program of preserving and advancing the great mathematical works that had come out of Alexandria. Not only did Hypatia write advanced academic works, but she also lectured and taught on these subjects. At the Alexandrian Museum, Hypatia taught and mentored some of the greatest Pagan and Christian minds of the day, including Orestes, the prefect of Alexandria, who later became a good friend. Surviving letters from one of her students tell us that her lessons included how to design an astrolabe, a kind of portable astronomical calculator which measured the altitude of stars and planets and would be used until the 19th century. Her father actually invented the astrolabe and it is likely that Hypatia assisted with this invention. Hypatia was also a popular teacher and lecturer on philosophical topics of a less-specialist nature, attracting many loyal students and large audiences to her public lectures. The Suda lexicon, a 10th-century encyclopedia of the Mediterranean world, records that Alexandria gave Hypatia a warm welcome and accorded her special respect. This respect was probably in part to do with the fact that Hypatia never married and was assumed a virgin up until her death, as well as her brilliant mind. Ancient Greek society thought celibacy was a virtue, so the people of Alexandria accepted and respected Hypatia, because she seemed to almost be sexless. This would have made her less threatening and allowed people (read: men) to celebrate her talents.

But as with many prominent characters in history, Hypatia met with a tragic end. While Hypatia was busy teaching in the Alexandrian Museum, Alexandria was becoming increasingly Christian, while Hypatia remained a pagan. While many scholars converted to Christianity to protect themselves against religious hostility, Hypatia refused to alter her beliefs and continued teaching pagan beliefs despite the risk it carried. This made her a prime target for violence in the increasingly turbulent Alexandria. Hypatia became the victim of a particularly brutal murder at the hands of a gang of Christian zealots on her way home from lecturing one day. As Alexandria mourned for her intellect, her murder made Hypatia a powerful feminist symbol. She became established as a figure for the affirmation of intellectual pursuits against ignorant prejudice.

Strangely enough, the most detailed accounts of Hypatia and her life come from records of her death. What is really special, and speaks to Hypatia’s character and impressive intellect, is that even in primary sources from hostile Christian writers, Hypatia was still portrayed as a generous soul, well-known for her love of learning and her expertise in teaching Neo-Platonism, mathematics, science and general philosophy.

Today Hypatia lives on as a symbol for feminists, a martyr to pagans and atheists and a character in fiction. Voltaire used Hypatia to condemn the church and religion. The English clergyman Charles Kingsley made her the subject of a mid-Victorian romance. Hypatia is the heroine in the Spanish movie Agora. The film tells the fictional story of Hypatia as she struggles to save the library from Christian zealots. Hypatia’s story and values live on and in some ways she is more alive in death that she was even in life.

– Tia Shah

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.