This is the first of two guest blogs by Megan Sormus, a PhD researcher at Northumbria University, whose research focuses on visualising femininities in contemporary women’s writing, DIY music subcultures, film and television. Writing for Girl Museum, Megan reports on Girls on Film, a recent conference on how girls and women are represented in films and television.

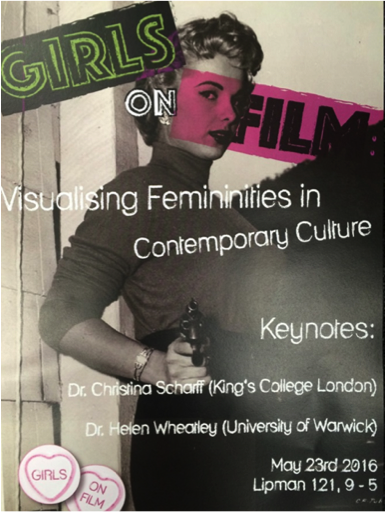

How are girls represented in the media? Is it right to question such representations? If so, how do girls begin to defy such depictions? How much control does the girl have in monitoring her own image? And finally, what do we truly mean when we think of the term ‚Äòmedia‚Äô? Recently, I organised a conference at Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, entitled ‘Girls on Film: Visualising Femininities in Contemporary Culture’ in an attempt to explore and answer such questions.

Initially, the concept of the conference was built around a celebration of Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema, which had just turned 40 when the initial planning of the conference began. Mulvey famously quoted:

The beauty of the woman as object and the screen space coalesce; she is no longer the bearer of guilt but a perfect product, whose body, stylised and fragmented by close-ups, is the content of the film and the direct recipient of the spectator’s look.

Here, Mulvey sets up how the female has been constructed into what she calls a ‘perfect product’. With this, the woman becomes the object, and her representation as woman and as perfect is merged and set in stone thanks to the popularity and widespread reach of mainstream media. Indeed, when we use the term media, it is important to remember that this is not just exclusive to television or film, but also to art, literature, performance and any other popular practice that allows us to visualise femininity in a specific way.

Influenced by this quotation, the role of Girls on Film was to unpick this illustration of the female as a perfect product, and to interrogate and unravel the pressures to live up to these idealistic expectations. It became clear from the mixture of speakers at the conference that girls were visualised in many forms and mediums and in all corners of academia. The presentations ranged from the Shakespearean female to the portrayal of the female body in Spanish and Italian Horror cinema; unruly women and anti-heroines in British comedy and American Drama, grrrl revolutions in contemporary consumer culture and the female body and feminist film theory.

Outside of academia and into the mainstream, we can trace a history of young female celebrities no longer content with the perfected and idealised path chosen for them: Christina Aguilera’s ‘dirty’ overhaul (2002) and Britney Spears’ psychological meltdown in 2007 are both examples of girls who are now a far cry away from their portrayal as the angelic ‘Mouseketeers’ of the The Mickey Mouse Club. A more topical example of this is Miley Cyrus’ raunchy transformation from her girl-next-door, sugary persona, Hannah Montana, into the riotous punk-fetishist image that caused extreme uproar. These are just a few examples of the way in which girls have worked to against the behavioural and pictorial expectations placed upon them.

Simply put, Girls on Film was created in order to end this constant idea that the female has to be a perfect product and alter the way that we as people of this contemporary culture visualise femininities. The overarching role of the conference was to portray the ways in which the female body has been manipulated, but most importantly, the ways in which the contemporary female now has the influence to manipulate, the media landscape so as to force the modern audience to (re)imagine femininities in contemporary culture.

-Megan Sormus

Northumbria University