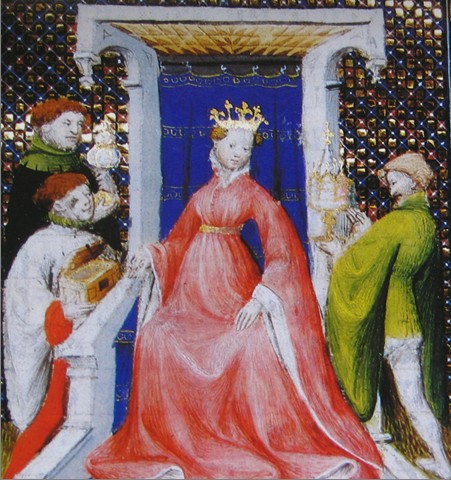

At just one year old, Joanna (c. 1328 – 1382) had a lot resting on her tiny shoulders: due to the untimely death of her father, she became heir to the throne of Naples. At the time, Naples was ruled by her grandfather, Robert the Wise. Joanna’s life and reign were full of conflicts, most of which were caused or exacerbated by her many husbands.

When Joanna’s father died it left Robert with a succession crisis. Did he leave the throne to his young granddaughter, or did he choose one of his nephews? In the end he went for his granddaughter, as it was less likely to complicate his own rule. To help secure Joanna’s claim, he married her to her cousin, Andrew of Hungary (who descended from Robert’s older brother). They married when Joanna was 5 and Andrew was 6. Robert died in 1343, leaving an ineffectual regency and a teenage Joanna poorly prepared for the queenship. His will made it clear that Joanna had been left the kingdom; there was no mention of Andrew as consort in Robert’s will. In the event Joanna died without children, the throne would pass to her younger sister.

Andrew was angry at being left virtually powerless in Naples and reacted by releasing the Pipini brothers from jail. The brothers had been locked up by Joanna’s grandfather for a variety of heinous crimes including rape, murder, and treason. Their goods had been confiscated and given to other nobles. The release lead to increased hostility toward Andrew, particularly from the nobles who benefited from the Pipinis’ imprisonment. During a hunting trip in 1345, Andrew was murdered in the middle of the night. There are conflicting opinions as to whether Joanna was involved in the assassination of her husband. While it is true they didn’t get on, Joanna would have known she would be a suspect. Additionaly, she was pregnant at the time and gave birth to her son, Charles Martel, a few months later.

Two years after Andrew’s death, Joanna married a cousin from the Taranto branch of her family (descending from one of Robert’s younger brothers), Louis. While he was more aware of Neapolitan politics than Andrew and a fierce warrior, he was an unpopular choice for many people. In choosing Louis she was also cutting out the Hungarian part of her family: Andrew had a younger brother they wanted her to marry; it was at this point they accused her of murdering Andrew.

Andrew’s older brother, Louis the Great of Hungary, launched an invasion of Naples in 1347 by using his brother’s murder as the perfect excuse to annexe Naples. Joanna fled to Provence, where her husband joined her shortly after. Her son with Andrew was sent to Hungary by his uncle, where he died aged 2. Joanna used her time in Provence effectively: she received a dispensation for marrying Louis, she sold Avignon to the Pope for 80,000 florins to help pay for the reconquest of Naples, and – perhaps most importantly for her reputation on the world stage – she was exonerated by the pope for the murder of Andrew.

By the time Joanna returned to Naples the Hungarian army had left, mostly because the Black Death had broken out. The Hungarians behaviour in Naples had made it easier for Joanna and Louis to be welcomed back. Older and more experienced than Andrew, Louis found it easier to take power from Joanna, and he became the decision maker and de facto ruler of Naples until his death in 1362 from an illness.

Joanna had another two marriages, the first to James IV, the deposed Kind of Malaga. Unfortunately, he was mentally unstable, having spent 14 years of his youth locked in an iron cage under the orders of his uncle Peter IV of Aragon. James resented Joanna’s unwillingness to share power and consequently spent long periods abroad trying to claim back his lands, where he died. Her final husband, Otto of Brunswick, was by far her most successful marriage.

Joanna died in 1382 in suspicious circumstances, though most people agree she was suffocated through the hands of Charles Durazzo, her first cousin. Being childless, she had sought to solve the succession by marrying Charles to her niece Margaret. When she changed her mind in favour of Louis I Anjou, Charles turned against her, capturing and mudering her.

It was a sad end to a hard reign. The periods Joanna ruled alone were infinitely more successful than when she was contending with jealous husbands. In less turbulent times she might have been remembered as a more successful queen. She had three children (two with Louis of Taranto), but they are all died young, and her aims to solve her succession arguably hastened her end.