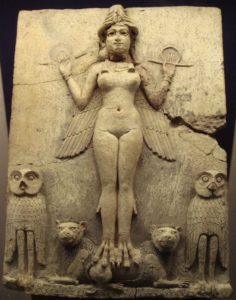

A tablet image depicting Inanna.

Inanna was an early Babylonian deity representing love and war, who arose from the city of Uruk in southern Babylonia. She was also later affiliated with the northern Babylonian equivalent Ishtar. As there are differing elements and stories associated with both, it is important to keep Inanna as a separate deity. Babylonian mythology is extremely similar to later Greek mythology, as Inanna closely resembles Zeus as the major deity in the Babylonian Pantheon. Her husband was the shepherd deity Dumuzi, who prior to their courtship was a mortal. He later rose to prominence as a chthonic deity through his association with her. The most well-known sources for Inanna date to around the second millennium BCE. However, she is mentioned in all major mythological and religious texts from the mid-fourth millennium BCE. She is also often listed as one of the four major deities.

The Jewish deity Lilith also finds her origins in Babylonian mythology. She is referenced in connection with Inanna in the tale of ‘Gilgamesh and the Hulupp Tree’ which dates to approximately 2000 BCE. While this tale is not an official tablet in the Epic of Gilgamesh, it is often used in connection with the twelfth tablet in order to help understand the narrative. The story tells of a Hulupp Tree that Inanna had planted in heaven in order to make a wooden chair. After years of growth, a “snake who knew no charm” was discovered nesting at the base of the tree thus making it impossible to cut down. This snake was referred to as Lilith and represented evil in heaven. Lilith pleaded with Gilgamesh who was able to slay the snake and cut down the tree. This narrative draws parallels to Chapters Two and three of the ‘Book of Genesis’ in the Jewish Tanakh and the Christian Old Testament. These tell of an evil serpent who attempted to lure Eve from obedience to Adam and God.

The main Babylonian reference to Inanna is The Descent of Inanna which dates to between 1900-1600 BCE. The narrative tells of Inanna who chooses to visit the underworld in order to see her sister, Ereshkigal. Inanna dresses in her finest clothes and jewellery before speaking to her chief advisor Ninshuba. She ordered Ninshuba to unleash the heavenly deities should she not return within a period of three days and three nights. Ereshkigal is unhappy about the visit and orders each gate to be closed to Inanna lest she remove an item of jewellery or clothing at each one. After passing through seven gates, she appeared naked before Ereshkigal and demanded to know the meaning of her actions. The judges appeared and passed an instant judgement against her, ensuring that she was unable to leave and as a result Inanna hung like a corpse.

Following her instructions, Ninshuba alerted the deities of her disappearance. Inanna’s father Eriki created the demons Kurgurra and Kalaturra to rescue her. Once again, in this story an original example of a Greek myth is found. This is seen with the idea of a person leaving the underworld demands a replacement to take their place. Because of this, demons rose up to heaven with Inanna to claim her substitute. Each of the deities that the demons attempted to abduct were dressed in traditional Babylonian mourning clothes for the loss of Inanna and out of respect, she saved each of them in turn. However, she discovered that her husband Dumuzi was not in mourning for her at all. She became enraged and ordered the chthonic demons to seize him as her replacement. It was eventually agreed, much like Proserpina in Latin mythology, that Dumuzi would spend half of the year in the underworld. His sister Geshtinanna was cursed into spending the remaining six months in his place. In a similar way to the Graeco-Romans, this myth was how the Babylonians rationalised the changing seasons with the disappearance of Dumuzi the shepherd deity representing Autumn and Winter.

Inanna is interesting as her myths draw parallels to many religions, both ancient and modern. This cements her and Babylonian mythology as a forerunner of ancient religion.

-Devon Allen

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.