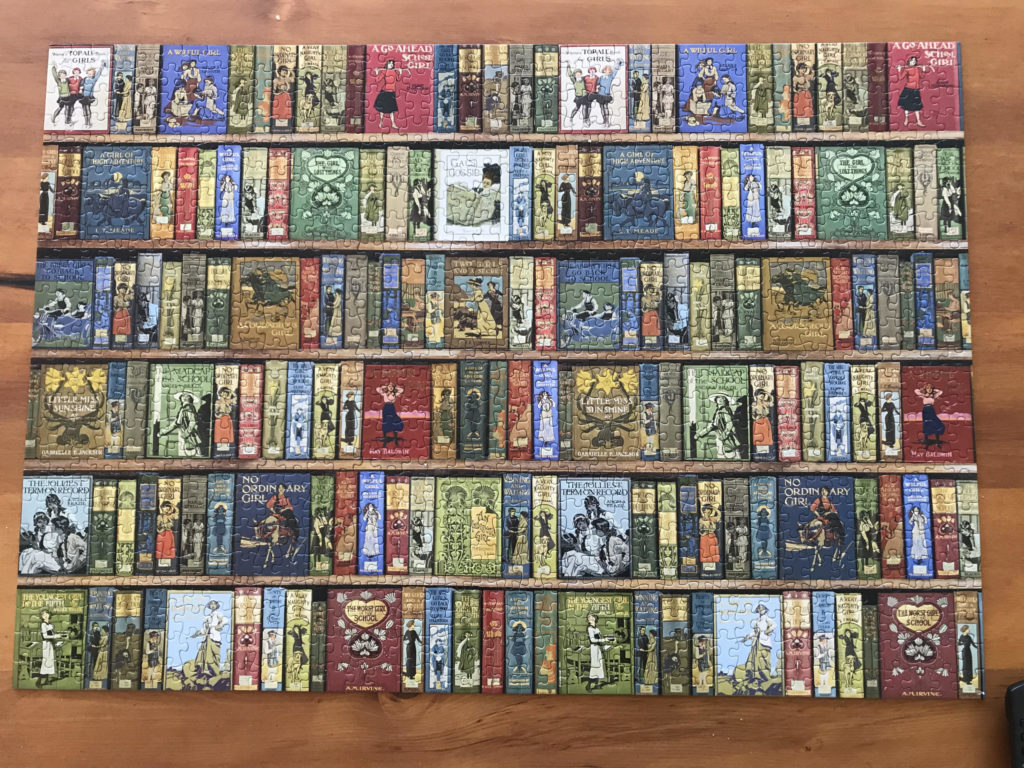

The Bodleian Library: High Jinks Bookshelves puzzle is filled with row upon row of early twentieth century school stories. Featuring schoolgirls of all kinds – courageous girls, willful girls, jolly girls, misbehaving girls, girls seeking ‘high adventure’– the completed puzzle shows just how popular the ‘school story’ genre of books once was, particularly in Britain in the early twentieth century. Since I had plenty of time to stare at these books while completing the puzzle, it made me realise how little I know about this once very popular genre. Time to investigate!

The first school story – and the first full-length novel written for girls specifically – was Sarah Fielding’s The Governess, or The Little Female Academy, published in 1749. A moralistic and didactic tale, it follows the lives of nine girls and their teacher over a period of nine days in the boarding school. While obedience is the central theme of the novel, the girls are also encouraged to learn to think for themselves and discover their own agency. Fielding’s novel was the beginning of a new genre – over the next hundred years, there were to be at least 90 published stories set in British boarding schools.

Girls’ school stories developed in parallel to boys’ school stories. As more and more schools were segregated by gender in the nineteenth century, school stories began to form two separate but related genres of girls’ and boys’ school stories. Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s School Days (1857) kick-started the mass popularity of the genre and promoted the values of loyalty, friendship, honesty, integrity and courage which would follow through many subsequent stories.

School stories were also published in other countries, including Germany, Soviet Russia, France, Japan and the United States. American classic children’s novels include the school stories What Katy Did at School (1873) by Susan Coolidge, Little Men (1871) by Louisa May Alcott and Little Town on the Prairie (1941) by Laura Ingalls Wilder. However, the theme of the school as a character formed by the pupils and their enjoyment is primarily a British and American phenomenon.

With an increase in girls going to boarding schools from the 1850s, especially after the 1870 Education Act, the popularity of girls’ school stories grew throughout the nineteenth century. Yet even for readers who had never been to boarding school, the stories presented a world of fast friendships, private languages, and academic and sporting opportunities that were extremely desirable and comforting.

In the 1890s, L.T. Meade (the pseudonym of Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith) became the most popular writer of the genre. One of her bestselling girls’ school stories was A World of Girls, published in 1886. Meade went on to produce a staggering 300 books in her lifetime. Her stories told of an enticing private world: one with its own social code created by girls for girls. The fictional school was a place where loneliness did not exist and where unconditional loyalty was the norm.

In 1906, Angela Brazil published The Fortunes of Phillipa. Deliberately breaking with tradition by expressing girls’ attitudes from the inside, the popularity of school stories reached new heights. Instead of using narrative view, Brazil adopted girls’ vocabulary and viewpoints. Her stories were characterised by their realism, her use of contemporary slang, and the fact that her characters can be ruthless, stupid, vain or pig-headed as well as brave, intelligent, kind and modest. While most girls’ stories focus on the value of self-sacrifice, moral virtue, dignity and honesty, Brazil’s girls are energetic characters who challenge authority, play pranks and live in their own world where adult concerns are not important.

Brazil went on to produce 45 full-length school stories and multiple short stories over forty years. Her work dramatically charted the transformation in girlhood ideology that occurred in the early twentieth century, a shift which culminated in the movement for women’s suffrage and the consequent changes in women’s roles and opportunities that occurred after the First World War.

By the time of Brazil’s death in 1947, the school story genre had become sufficiently embedded in girls’ reading experience to flourish without her. A few of her famous successors include Enid Blyton, Elinor Brent-Dyer, Dorita Fairlie Bruce and Elsie Oxenham. Brent-Dyer’s Chalet School series and Blyton’s Malory Towers and St. Clare’s school series both went on to become extremely popular. The Chalet School series ran to an amazing 58 books in total. Seventy years after the first book appeared in 1925, the series was still selling 150,000 copies a year without ever having gone out of print.

The peak period for school stories was between the 1880s and the end of the Second World War. This was helped by the growth in boarding school numbers: in 1900 there were just 20,000 girls at girls’ grammar schools in England, but by 1920 this figure had already grown to 185,000.

The genre of girls’ school stories remained popular throughout the twentieth century, with Enid Blyton continuing to write throughout the 1940s and 50s. One of my favourite school story writers is Antonia Forest, who published her school stories about the Marlow siblings between 1948 and 1982.

As the genre developed, girls’ school stories came to represent a self-contained world of girlhood liberation, a temporary haven from reality. In many ways, school stories are fantasy stories, preoccupied as much with the actual shaping of an imaginary, alternative world as with the characters and events that occur within it. The popularity of school stories is as alive today as ever – think especially of the mass popularity of the Harry Potter series.

Ultimately, girls’ school stories were (and are) popular because they teach girls that they can do anything which boys can do – play sport, succeed academically, go on to higher education, pursue careers and have adventures. Girls can be leaders, they can rebel, they can think for themselves and they can do anything they set their heart to. One thing is for sure – the ideas and lessons in these twentieth century girls’ school stories are still as important and relevant now as they were a hundred years ago.

-Rosalie Elliffe

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.