Daily Struggles

What is daily life like for a girl in India? Is it similar to or different from our own? Use the toggles below to explore some of the issues that girls face every day in India.

Education

Indian students, Biswarup Ganguly, 2010. Wiki Commons.

“When girls are educated, societies are transformed. Economies grow, health improves and everyone benefits.” – Circle of Sisterhood

For decades, there had been huge inequalities in the numbers of girls and boys attending school in India, at both a primary and a secondary level. However, the Right to Education Act passed in 2009 made education free and compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 14. The new law also provided more funding for educational infrastructure. Now, 98% of dwellings have a primary school (class I-V) within 1 kilometer and 92% have an upper primary school (class VI-VIII) within 3 kilometers.

Recent statistics have demonstrated that the situation is positive for achieving educational gender equality. For example, enrollment rates in primary school have reached 96% since 2009, with girls making up 56% of the new students between 2007-2012. In higher education, 45.9% of enrolled undergraduate students and 40.5% of enrolled PhD students in India are now women.

A greater investment in education, improved infrastructure, and new laws and campaigns are to thank for this progress towards universal education in India. Programs such as the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, launched by the federal government in 2000 to extend elementary education to every child from the ages of six to 14; state government incentives, such as the provision of free bicycles to school-going girls in Bihar; and the setting up of a greater number of government and private schools contribute to more girls being educated in India.

However, despite the positive picture painted, there are still 3 million girls out of school in India. While enrollment rates have significantly increased, drop-out rates are still very high. Nearly 25% of girls leave school before completing primary school and more than 40% of the remainder don’t complete secondary school. Especially in rural areas, there are substantial factors that limit girls’ ability to go to school and many still believe that female education is neither mandatory nor ideal.

Across India, there are also problems with the standard of education, especially in rural areas, even when school infrastructure and facilities have improved. For example, fifth grade students in government-run schools in nine Indian states cannot read second grade textbooks (Annual Status of Education Report). In addition, many teachers are not formally trained and there is a chronic shortage of teachers; India would need an additional 689,000 teachers to fully teach the primary school population.

What prevents girls from going and staying in school?

Family responsibilities & gender norms: Girls provide free labor for the family, so many girls are kept at home because it is a better payoff than going to school. Having a girl attend school is not considered valuable to the whole family, and there is a belief that a girl’s earnings will only benefit her marital family, so parents are discouraged from investing in their daughters’ education. In India, cultural decisions are frequently deferred to elders, so often girls have no choice in whether they go to school or not!

Safety concerns & to protect family honor: Concerns over the school distance and safety of a girl getting to and from school is a critical barrier for sending girls to school, especially in rural areas (MacArthur Foundation). As a girl gets older this is a particular problem, as any sexual harassment could dishonor the whole family. The marital family can also raise the dowry if they suspect the bride has been in school with boys during puberty. If the dowry cannot be paid, the bride runs the risk of being ruined, or worse, being killed.

Lack of adequate facilities: Schools are unable to provide safe and sanitary facilities for young girls. This is often exacerbated by basic infrastructural problems: roads, running water, and electricity are often scarce. Inadequate facilities is a particular problem during menstruation, when many girls are forced to miss school.

Child marriage: It is estimated that 47% of girls in India are married before their 18th birthday. Although child marriage is illegal in India, it is still prevalent, especially in rural areas, and laws don’t apply to any Muslims in India. Once a wife, there is rarely an opportunity to attend school and even before the marriage education is often discouraged.

Why is education so important for girls?

It may seem like a silly question, but the truth is most of us do not realise the far-reaching impacts of education.

Education empowers women to overcome discrimination. Girls and young women who are educated have greater awareness of their rights, and greater confidence and freedom to make decisions that affect their lives, improve their health, and boost their work prospects.

The impact of female education is extraordinary.

- Life expectancy rises by 2 years for every 1% increase in literacy (U.S. Census Bureau 1998)

- For every year of secondary school, a girl’s future income raises 10-20%. If girls received the same educational opportunities as boys, the Indian economy would grow by nearly $33 billion per year (World Bank, 2010)

- When women earn an income, they reinvest 90% of their income in their families and communities (Phil Borges, 2007)

- An educated mother is more than twice as likely to send her children to school (UNICEF, 2010)

- If all women in low and lower middle-income countries completed secondary education, the lives of three million under-five-year-olds would be saved every year (UNICEF, 2010)

- If India enrolled 1% more girls in secondary school, its GDP would rise by $5.5 billion (CIA World Factbook, 2011)

- Girls with secondary education are 6 times less likely to be married as children (International Center for Research on Women, 2006)

- A literate mother has a 50% higher chance that her child will survive past the age of 5 (UNESCO, 2011)

Girls’ education is a strategic development priority. Better educated women are more self-reliant, they tend to be healthier, participate more in the formal labor market, earn higher incomes, have fewer children, marry at a later age, and enable better healthcare and education for their children. Combined, these factors can help lift households, communities, and nations out of poverty.

Menstruation

Poorna’s story

My name is Poorna, I am 13 years old and I have started my first period. I live in Sitatold, a small village in the state of Maharashtra, in India. This morning, when the bleeding started my mother walked me very far into the forest, away from the village to stay in a hut. My mother brought me my dinner a few hours ago but now it’s dark and I’m scared. The roof is leaking from the rain and I can hear the cries of animals. I’m scared that one might come in through the gaps in my hut. I wish there was someone here with me. Mother says if you’re lucky other girls will be in the hut with you. I am not lucky. I hope someone will come tomorrow so I will have someone to talk to. It will be so boring here for three days with nothing to do. I just want to go home. I don’t understand why I have to be left in this hut by myself.

Controversy

Menstruation in India has recently been caught in the middle of the controversy about gender equality. This controversy has resulted in many people, both men and women, questioning various accepted notions, traditions, and practices surrounding menstruation.

Attitudes towards menstruation in India are heavily affected by religious teachings on the subject – and sadly they are not hugely positive. Periods are taboo in India, across all religious groups and classes. Menstruating girls and women are overwhelmingly considered impure, even by themselves! The shame attached to menstruation has fostered a culture of silence around the topic which has led to a massive lack of education, and therefore bad practices surrounding menstruation.

Did you know that only…

55% of Indian girls think menstruation is normal.

23% of Indian girls know that blood during menstruation is the lining of the womb shedding.

70% of mothers consider menstruation “dirty,” perpetuating a culture of silence.

88% of Indian girls are subject to restrictive practices while menstruating.

Menstruation in India has a serious and damaging impact on many young girls and women. The Dasra foundation (2014) found that 23% of girls in India dropped out of school when their periods began because of the lack of adequate provisions, like a private toilet or sanitary pads. Those who do stay in school when they reach puberty generally do not go to school during their periods, having a serious impact on their education.

The health of girls all over india is also at risk because of a lack of knowledge and provisions. In only 7 of India’s 36 states and union territories did 90% or more women in the 15-24 age group use hygienic protection during menstruation, according to the latest national health data. Not even 50% women used clean methods of dealing with menstrual hygiene in 8 states and union territories – according to the National Family Health Survey (2015-16). The Rutgers study revealed that for the absorption of the menstrual blood, 89% women used cloth, 2% used cotton wool, 7% sanitary pads and 2% ash. Among those who used cloth, 60% changed it only once a day. These practices help explain why 14% girls reported menstrual infections.

Not only are hygiene practices and education suffering due to the taboo surrounding menstruation in India, but girls and women are also not allowed to participate in social or religious life due to their perceived impurity. In many areas they are banned from entering temples or cooking food in their own homes while menstruating. They have to wash their clothes separately and sometimes are not even allowed to touch anyone or anything.

In some parts of India girls are even isolated from the community while menstruating. They are banished to goakors – huts usually located in the forest, away from the community. These huts are basic at best, with no kitchen and no beds; women usually sleep on the floor with just a thick sheet for a mattress and food is brought to them by family members. If they’re lucky, there are other women there at the same time. As the goakors are often located in the forest, it is not uncommon for wild animals to appear in and around them, and sadly there have even been reports of women dying while staying in goakors.

The Role of Religion

Historically, ideas about menstruation and the cultural practices surrounding it have been informed by religion. All religions have slightly different beliefs about menstruation, but menstrual blood is considered impure by the majority of religions and cultures.

Photo by David Watson.

Hinduism perpetuates the belief that women are impure when menstruating. The Vedas and other holy scriptures detail various restrictions on menstruating women, including bans on sexual intercourse, exercise, household activities, and bathing. Additionally, menstruating girls are not allowed to eat certain foods or attend religious and spiritual activities. Since menstruation is thought to make girls weak, they spend their menstrual periods resting in isolation.

Yet, Hindus also celebrate menstruation in various forms. Ritushuddhi is a Hindu samskara, or rite of passage, associated with a girl’s first menstruation cycle. This ceremony includes dressing the girl in a sari and announcing their maturity to the community. In Tamil Nadu, the celebration is extravagantly carried out for three days, where it is called “Manjal Neerattu Vizha” (turmeric bathing ceremony). In this festival, the girl undergoes ritual seclusion, ritual bathing, and many other local customs, including a turmeric bathing ceremony. The girl also wears a sari or half-sari for the first time.

Other religions practiced in India place similar taboos on menstruating girls. Islam dictates that menstruating women are not supposed to touch the Qu’ran, enter the mosque, offer daily prayers, fast, or have sex for a full seven days. In the Christian Bible, menstruating women are seen as unclean and, in the Eastern Orthodox church, must refrain from partaking of sacraments or touching holy items and religious icons. Finally, in Jainism, several texts consider menstrual blood to be impure and do not allow girls to cook or attend temples.

However, there are some religions that view menstruation for what it is: a natural process. Buddhists view menstruation as “a natural physical excretion that women have to go through on a monthly basis, nothing more or less.” Additionally, Sikhism makes it clear that menstruation is a God-given process and the blood of women is required for the creation of any human being.

“Menstruation is not an illness” reads a message on a sanitary napkin during a protest in Kolkata in April. Photograph: Arindam Shivaani/NurPhoto/Rex Shutterstock.

#periodpositive

As the majority of the population is Hindu, many girls across India suffer from isolation and social restrictions every month during their period. However, the very notion of being impure is currently being challenged, and protests in India are starting to change the way people think about menstruation, as well as educate the population.

There have been many movements to put an end to discrimination against menstruating women; women from all cultures are appalled at the restrictions Indian girls face e.g. #padsagainstsexism, #happytobleed, and #periodforchange.

These protests are trying to break the taboo around menstruation in India and promote a healthy relationship with this natural process. And so far, they might be working. In February 2017, news appeared that government schools in Delhi will hold period talks where questions around menstruation will be answered by the NGO Sachhi Saheli under a campaign called “Break the Bloody taboo.” The NGO, which started imparting these lessons in slums and some government and private schools in East Delhi, will expand its reach now, after a two-month-long pilot project they conducted for the Delhi government.

To make the taboo topic an important and necessary subject of discussion in India, Aditi founded Menstrupedia in 2012 with the aim of helping young girls understand and deal with puberty and sex education in a positive manner, after her embarrassing experience of periods as a child.

“When girls [in India] get their periods, they are considered impure for those 7 days,” Aditi tells TIME. “That is how I grew up, seeing myself as impure. That sense of shame was instilled in me from a very young age.”

Aditi wrote a book in Hindi, explaining everything she lerned about puberty and the changes in the body. The book is now available in English, and is being spread around the world. Menstrupedia has a website and a comic, which is a guide to healthy periods, used by more than 90 schools, 25 NGOs and 85,000 girls across India.

Religion

The Indian subcontinent is the birthplace of four of the world’s major religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. Both Hinduism and Buddhism originate from India specifically. Religion in India, therefore, has always been characterized by a diversity of beliefs and practices. Religion has always been an important part of the country’s culture.

Since India was made a secular state in 1976, all religions are treated equally by the state. India declared the right to freedom of religion to be a fundamental human right; religious diversity and religious tolerance are established in India through the law and by custom. Although separate religions are practiced in India by different communities in different areas, over the centuries there has been significant fusion between the various religious cultures in India.

Rituals, worship, and other religious activities are prominent in an individual’s daily life; it is also a principal organiser of social life. Most Indians engage in religious rituals on a daily basis, mostly based in the home. However, the observation of rituals varies greatly among regions, villages, and individuals. Devout Hindus perform daily chores such as worshiping puja, fire sacrifice called Yajna at dawn after bathing, and reciting from religious scripts like Vedas.

It is not just rituals, even diet is significantly affected by religion! Almost one-third of Indians practice lacto-vegetarianism, although vegetarianism is less common amongst Sikhs and almost uncommon among Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Jainism requires everyone to be vegetarian. Furthermore, the religion also bars Jains from eating any vegetable that is dug from the ground.

Other religious rituals that are not daily but are very popular across India:

Holi

Holi participant, Biswarup Ganguly, 2012. Wiki Commons.

Holi is a Hindu spring festival celebrated in India and Nepal, also known as the “festival of colours” or the “festival of love.” The festival signifies the victory of good over evil, the arrival of spring, and the end of winter. It is also celebrated as a thanksgiving for a good harvest. Holi lasts for a night and a day, starting on the evening of the Purnima (Full Moon day) falling in the Vikram Samvat Hindu Calendar month of Phalguna (between the end of February and the middle of March).

Holi celebrations start on the night before Holi with a Holika Dahan where people gather, perform religious rituals in front of the bonfire, and pray that their internal evil be destroyed. The next morning is celebrated as Rangwali Holi – a free-for-all festival of colours, where people smear each other with colours and drench each other. This occurs in the streets, parks, outside temples and buildings. In the evening, people dress up and visit friends and family.

Although predominantly a religious festival, this colourful tradition has caught the imagination of the west, where in recent years Holi festivals and colour runs have become increasingly popular across Europe and America.

Mehndi

Henna, Melissa Gupta, 2005. WikiCommons.

Girls in India participate in many types of artistic practice for personal rituals. Mehndi, or henna body painting, is one of them. Mehndi is a form of body art which was developed in ancient India and is one of the oldest forms of body art conceived by man – references to uses of henna can be traced back to the Bronze age. Decorative designs are created on a person’s body using a paste of powered dry leaves of the henna plant.

Mehndi holds cultural significance in India. At special occasions, ceremonies and festivals, such as weddings or Karva Chauth, mehndi is used to decorate women. The mehndi ceremony is a very important part of Indian weddings, as mehndi is one of the sixteen adornments of an Indian bride. It is traditionally a women-only ceremony, organised by the family of the bride, and in the presence of female friends and relatives. According to the ritual, the bride does not step out of the house after this ceremony, so it usually occurs on the morning before the wedding. The henna for the bride’s ceremony has to arrive from the groom’s family along with some other gifts like fruits, dry fruits, and sweets. Designs are more elaborate and depending on what the bride prefers, the henna is applied on the front and back of her palms, forearms to above the elbows, and on the feet up to the knees. Elderly ladies sing traditional mehndi songs with dholaks and other musical instruments. Female relatives of the bride also get mehndi applied to their hands, although the designs are not as elaborate as the bridal mehndi. Henna is known for its cooling properties and is supposed to calm the bride’s nerves when applied to her hands and feet.

This ritual is not only part of Hindu weddings in Northern and Eastern India but also a part of the wedding rituals among Indian Muslims. The ceremony is observed in countries adjoining India like Pakistan and Nepal, as well as in several Arab countries in the Middle East.

Raksha Sutra

Rakshasutra, Manoj Vishvakarma, 2008. Wiki Commons.

Raksha Bandhan is observed on the last day of the Hindu lunar calendar month of Shraavana, which typically falls in August. Raksha Bandhan, or Rakhi, is a Hindu festival that celebrates the love and duty between brothers and sisters. On this day, sisters of all ages tie a talisman, or amulet, called the rakhi, around the wrists of their brothers, ritually protecting their brothers. In return they receive a gift.

To many, the festival brings people together across religion and ethnicity, ritually emphasizing harmony and love. Of special significance to married women, Raksha Bandhan is rooted in the practice of territorial exogamy, in which a bride married out of her village or town, and her parents, by custom, do not visit her in her married home. In rural north India, where territorial exogamy is popular, large numbers of married Hindu women travel back to their parents’ homes every year for the ceremony. In urban India, where families are increasingly nuclear, and marriages not always traditional, the festival has become more symbolic, but remains highly popular.

Among women and men who are not blood relatives, a tradition has also developed of voluntary kin relations, cemented through the tying of rakhi. This tradition cuts across caste, religious, and class lines. The following video is a cartoon explaining the story behind the Raksha Bandhan tradition:

Rangoli

Onan Pukolam, Manoj Krichna, 2006. WikiCommons.

Rangoli is a girls’ artistic practice primarily associated with festivals that originated in India. Patterns are created on the floor in living rooms or courtyards using materials such as coloured rice, dry flour, coloured sand, or flower petals. It is usually made during Diwali or Tihar, Onam, Pongal and other Indian, Bangladeshi and Nepalese festivals related to Hinduism. Designs are passed from one generation to the next, keeping both the art form and the tradition alive. The purpose of rangoli is decoration, and it is thought to bring good luck. Design depictions may also vary as they reflect traditions, folklore and practices that are unique to each area.

Here are some Rangoli colouring pages you can print out and decorate as you like!

The following video shows a Rangoli being created:

Work

India is traditionally a patriarchal society and many still believe that a girl’s place is at home, looking after her family, not providing for them. This limits the sectors that girls can work in, and also negatively affects their aspirations.

Sadly, women in India do not earn much. Most female workers are considered unskilled, earning roughly 85 rupees ($1.50) per day.

The census does not count informal female workers – of which there are thousands, possibly even millions! Lots of the female work crosses over with housework so is difficult to classify. Women and girls who are not in paid employment still cook, care for children and elderly relatives, do domestic chores, and in rural areas, tend to animals and gardens. All this is invisible work, unpaid and unrecognised.

So what is the current situation?

As many Indians believe a woman’s sole job should be looking after the family, it is not surprising to find that the number of working-age females working is lower than the world average of 50%. It is almost 50% lower than the world average, with only 27% of working-age females in paid employment from 2015-16.

What makes this statistic even more surprising is that, from 1993-94, 43% of working-age girls in India were in paid employment. Not only that, but India has had a huge population boom in recent years. While more than 24 million men joined the work force between 2004-05 and 2009-10, the number of women in the work force dropped by 21.7 million. Today, just one in five urban Indian females are in the labor force. This worrying trend suggests the boost India’s economy receives from its vast young population will be negated.

If female employment was brought on par with male employment in India, the nations GDP would expand by as much as 27%! India desperately needs to find a way to encourage girls to join the workforce and increase benefits to make them stay.

The real mystery is that, according to the New York Times (2015), 1/3 of women in the household say they would like a job, this statistic rising to almost 1/2 in educated urban women in India. So why are the numbers of women working in India decreasing?

Two reasons have been suggested for these trends:

- An increase in wealth has led to less women working as family income stabilises and extra income is not needed.

- More girls are studying and therefore less are in employment.

But, there’s actually declining labor force participation rates across all age groups, education levels and in both urban and rural areas. Mysterious…

However, there are some clear reasons for why the numbers of Indian women working remain low. A hint: gender inequality is at the heart of this matter.

- Lack of suitable jobs. Many rural women find it convenient to do part-time jobs near their home, therefore farming has always been popular. However, the number of farming jobs has been shrinking, without an equal increase in other employment opportunities. The jobs that are available are marginal, low paying, insecure, and backbreaking.

- Cultural reasons and gender norms. Even in the 21st century, there is a limit on which sectors will employ women in India due to traditional notions. Many jobs are still not deemed suitable for women, such as work in the transportation sector, with its late nights and solo travel. Many of the “top” jobs, such as government positions, are still off limits to women, which severely impacts the aspirations of young girls. The belief that girls do not need to be educated, and practices such as child marriage and immediate motherhood, also keep girls from learning the skills they need to help support their families and become independent.

- Discrimination. While the Constitution of India prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, place of birth, or social status, there is still lots of discrimination against females. In India it is commonplace for employers to probe the marital status and family situation from a woman seeking a job. Employers are less likely to employ females they think may get pregnant in the near future. Women also face poorly enforced maternity leave policies, restrictions on the use or toilets or mandatory break periods, and sexual harassment in the workplace.

- Pay gap. Women earn 57% of what their male colleagues earn for performing the same work, this pay gap widens as a woman becomes more educated.

So how can we encourage more girls to enter into the job market and stay there?

The picture is not all bleak! In India, in professional sectors where there has been sharp expansion, and where working conditions are visibly good, women have done really well. By highlighting these emerging role models and how they have broken their glass ceilings, we can give girls the visibility and inspiration to pursue their dreams.

One example is financial services: while only 1/10 Indian companies are led by women, more than half of them are in the financial sector. Today women head both the top public and private banks in India. The following video features a BBC News report on how the financial sector is encouraging women to enter – and rise – in the workforce:

<a href="https://youtu.be/VAMnay4gjEg">https://youtu.be/_K1agltzolA</a>

Sports

The benefits of sports are not confined to the playing field. Sports can enhance girls’ physical well-being and encourage girls to lead healthier and more active lives. Playing sports also helps build girls’ leadership skills and self-esteem, cultivate teamwork and a sense of community, and challenge inequalities and stereotypes about women’s roles and abilities. In its charter adopted in 1977, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) identified sports as a human right and a means to achieve social needs. In recent years, the UN, along with many other organizations, has emphasized the critical role of sports in gender empowerment.

Despite this recognition, girls in India face barriers to participating in sports. Female athletes and their achievements continue to be overshadowed by male athletes, and girls’ teams receive less support and investment than their male counterparts. Girls also face a range of obstacles, including poor infrastructure, harassment, and resistance from family members. In overcoming these obstacles, girls in India are making a name for themselves in a variety of sports, from boxing and hockey to tennis and cricket.

Mithali Raj

Mithali Raj batting for India women against England in Truro in 2012. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Cricket is by far the most popular sport in India. The current captain of the Indian women’s cricket team, Mithali Raj, made her debut for the team at just sixteen. During her first game, she scored an unbeaten 114 runs. She is the currently the all-time leading run-scorer for India in all formats of the game (test matches, one-day internationals, and T20) and led her team to the Women’s World Cup final in 2017. Her achievements have earned her the nickname the “Tendulkar of Women’s cricket,” drawing comparisons with perhaps the most famous Indian cricketer, Sachin Tendulkar. There are plans to make a movie about Mithali’s life, which she hopes will inspire more young girls to pursue sports as a career.

Saina Nehwal

XIX Commonwealth Games-2010 Delhi: Indian shuttler Saina Nehwal in action against her Barbados opponent during their match in the preliminary round of badminton event, at Sirifort Sports Complex, in New Delhi on October 05, 2010. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After cricket, badminton is the second most played sport in India. One of the athletes credited with increasing the popularity of the sport is Saina Nehwal. The daughter of badminton players, Saina grew up around badminton courts and had an interest in sports, from swimming to karate, from a young age. She won a bronze medal at the 2012 London Olympics, making her the first Indian badminton player to win an Olympic medal. She has also won medals at the World Championships, the Commonwealth Games, the Asian Championships, and the Asian Games. Saina is also a role model off the badminton court and is known for her charitable work and supporting a variety of causes.

Pusarla Venkata Sindu

NAC Jewellers Honors Olympic Silver Medalist PV Sindhu.

Like Saina Nehwal, Pusarla Venkata Sindhu has won numerous medals for her achievements on the badminton court. She began playing when she was eight, and ten years later, she became the first Indian woman to win a medal in the singles competition at the Badminton World Championships. At the Rio Olympics in 2016, she became the first Indian woman to win an Olympic silver medal and the youngest Indian to win a medal at the Olympics.

Sakshi Malik

Indian wrestler Sakshi Malik at a promotional event in 2016. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Wrestling is on the rise among girls in India, in large part due to the success of female wrestlers like the Phogat sisters and Sakshi Malik. Their achievements have challenged stereotypes about wrestling and perceptions that the sport is only for men. Sakshi comes from a family of wrestlers and started competing in the sport at age 12, despite facing protests alongside her coach, Ishwar Dahiya, over his decision to train her. Sakshi’s resilience and determination paid off, and at the 2016 Rio Olympics, she won a bronze medal in wrestling, becoming the first Indian female wrestler to win an Olympic medal. Upon winning the medal, she used the occasion to encourage other girls to persevere in the face of adversity: “To those who told me I am a girl and I could not wrestle, I want to say please show some trust in girls, they can do everything.”

Saba Anjum Karim

Saba Anjum Karim. Source: Alchetron: Free Social Encyclopedia for the World

Saba Anjum Karim began playing field hockey with boys in her neighborhood at the age of nine, and by fifteen, she was a member of the international team. At seventeen, she was the youngest participant in the hockey competition at the 2002 Commonwealth Games, in which the India team won a gold medal.(The victory inspired the Bollywood film Chak De! India (Go for It! India). In 2011, she was named captain of the team. She hopes to open an academy to teach hockey and encourage the next generation of girl hockey players.

Arunima Sinha

Arunima Sinha. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Arunima Sinha was already an accomplished volleyball and football (soccer) player in India when her life changed irrevocably in 2011. While travelling on a train, she was pushed off of the train during an attempted robbery. Her leg was crushed by another passing train, and doctors had to amputate it in order to save her life. As she recovered from this life-changing, horrific event, Arunima set her sights on a new challenge: climbing Mount Everest. Just two years after her leg was amputated, she accomplished this goal, becoming the first female amputee to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Arunima now works to help others and hopes to open a sports academy for the poor and differently-abled children.

Indian Girlhood in Art

One of the primary ways girls communicate their experiences is through art. During the 20th and 21st centuries, art became a way for girls to reflect on, interpret, and discuss their childhoods in India.

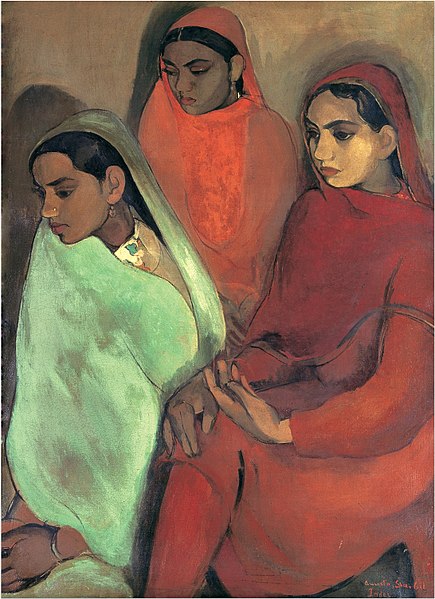

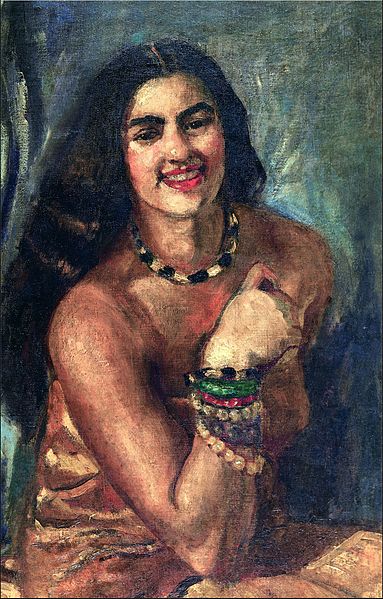

Amrita Sher-Gil, the “Indian Frida Kahlo”

Born in 1913, Amrita has been recognised as one of the greatest avant-garde women artists of the early 20th century and a pioneer of Indian art. She started painting at a young age, and as a teenager moved to Italy to attend Santa Annunziata, an art school in Florence. A few years later, at the age of sixteen, Amrita sailed to Europe and trained as a painter in Paris, drawing inspiration from artists such as Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin.

Due to her use of rich colors more common in eastern style paintings, and a longing to go back home, she returned to India in 1934. Amrita wanted to rediscover the traditions of Indian art and traveled throughout India, expressing her Indian roots and representing the life of Indian people through her artistic practice. In 1941, only a few days before the opening of her first major solo exhibition, Amrita died. She was 28.

Amrita’s art has influenced many generations of Indian artists. She is recognized as a role model for young women due to her depiction of the plight of women in her paintings. Amrita is often referred to as the “Indian Frida Kahlo.” The majority of her works are at the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi. In 1976, she was recognized by the Indian Government as a National Treasure artist.

Bride’s Toilet by Amrita Sher-Gal, Oil on Canvas, 1937. Held by the National Gallery of Modern Art, India.

Young Girls by Amrita Sher-Gil, oil on canvas, 1932. Held by the National Gallery of Modern Art, India.

Group of Three Girls by Amrita Sher-Gil, oil on canvas, 1935. Held by the National Gallery of Modern Art, India. This painting won Amrita a gold medal from the Bombay Art Society.

Self-Portait by Amrita Sher-Gil, Oil on Canvas, 1930. Held by the National Gallery of Modern Art, India.

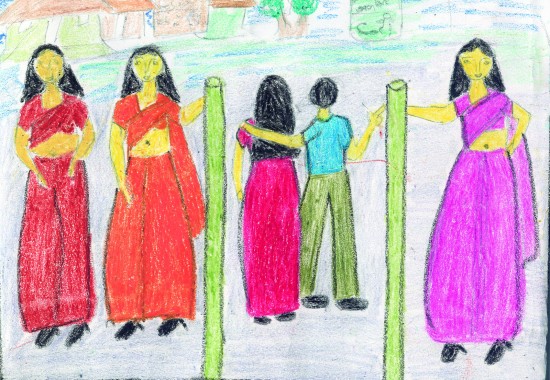

Sanjana Aggarwal

Sanjana is 14 years old and is studying in NBS, New Delhi, India. When she grows up, she wants to become a doctor.

India Rising: Apne Aap

Being a girl in India is tough. Every day, girls face discrimination, violence, and struggle for survival – all because they are born female. Through a collaboration with Apne Aap, which helps marginalized women and girls work collectively to lift themselves out of the sex industry, we invited girls to explore their everyday lives through poetry and photographs. Check out their reflections below.

“A trafficker,” Abhimanyu, The place where we live is called red light area, 2004. © Apne Aap, Kolkata.

“A trafficker is a person who hands over boys and girls to other people in exchange of money. They have large factories in Delhi and America. These factories engage five and six-year-old boys and girls. They are so young that I doubt if they can spell their parents’ names and addresses. They are sold again, when they are older. Young boys and girls are trafficked this way.” —Abhimanyu, 15

“They comes dressed like policemen,” Piyali, The place where we live is called red light area, 2004. © Apne Aap, Kolkata. Drawing by a child depicting how traffickers dress up as policemen to come into people’s home to take children.

Art Therapy, AAWW Community Center at Najafgarh, near New Delhi, 2010. © Apne Aap, Kolkata. Girls gathered for mandala workshop at the AAWW Community Center. This center has recently moved into a much larger space one town over. All of the members are still active.

Farida & Karishma after a dance therapy class at the KGBV in Simraha, India. Photographer: Morgan Metcalf, 2010. “I volunteered with Apne Aap for 3 months in 2010, teaching English and life skills to a group of fifty girls at the KGBV (girl hostel/school) in Simraha, Bihar. I lived with the girls in their hostel 4-5 days of each week, so I ate meals with them, prayed with them, and participated in activities with them. The girls so enjoyed the dance therapy sessions (a two-day class with teachers who travelled from Delhi), and it was a wonderful cathartic and growing experience.”

Girls sewing doll clothes at the Apne Aap Community Center, Rampur, India. Photographer: Morgan Metcalf, 2010. “During my last two weeks in India, I took a few trips to the Apne Aap Community Center in Rampur with Kalpanna, one of the center’s teachers. During the few days I spent with these girls we taught each other games, sang songs, they showed me their sewing projects, and I visited their homes/families.”

Lessons, Uttri Rampur community center, Forbesganj, Bihar. 2010 © Apne Aap, Kolkata. In addition to art and dance therapy, other activities are held at the community centers, including after school tutoring sessions and non-formal education courses.

Mandalas, AAWW Community Center at Najafgarh, near New Delhi, 2010. © Apne Aap, Kolkata. Community center art therapy workshop where the girls made mandalas that represent their souls and the color and life they have inside of themselves.

Uttri Rampur community center in the red light area of Forbesganj, Bihar. 2010 © Apne Aap, Kolkata. “This photo was taken shortly after Apne Aap staff and women in our Self-Help Group program painted the walls of the community center. Among the communities we work with in Forbesganj is the Nat Caste/Tribe, which has practiced intergenerational prostitution for the last 100-200 years as the accepted means of income. In beautifying the centers, they become a source of pride for the community and they feel ownership over them, which is really important.”

'The Story of My Desires' - Anwari Khatun, age 16

इच्छाओ की कहानी

यह एक ऐसी लड़की की कहानी है जो छोटे शहर में रहती है | वह अपने माता -पिता के साथ रहती है |वह बहुत खुश रहती थी ;लेकिन एक दिन ऐसा आया की किस्मत ने उसे अपनी माँ से हमेसा के लिए अलग कर दिया |अब वह अपने पिता के साथ रहने लगी कुछ दिनों के बाद ही उसके पिता के साथ रहने लगी कुछ दिनों के बाद ही उसके पिता ने अपनी बहन अपनी बहिन के यहाँ बेटी को भेज दिया | लड़की की बुआ उससे बोहत काम करवाती थी तथा उस पर और भी कई तरह की अत्याचार करती थी | यह बात जब उसने अपने पिता को बताई तो पिता उससे अच्छी जगह ले जाने का बहाना देकर कुछ पैसो के खातिर उसे बेच दिया | वहा के लोग भी उसके साथ बुरा बर्ताव ही रखते थे | अचानक एक दिन उसे एक अच्छा लड़का मिला जिसे वह बचपन से जानती थी उसे देखकर थोड़ी रहत मिली | वह आदमी उस लड़की को वहा से बचा कर तो ले गया लेकिन कुछ दिनों के बाद उदकी भी नियत ख़राब हो गई | अपनी जिंदगी के दुखो से मजबूर होकर लड़की ने खुदखुशी कर लिया |

अनवरी खातून

उम्र – 16

This is the story of a small town girl. She lived happily with her parents till one fateful day when she became separated from her mother forever. She then began to live with her father. After a few days he sent her over to live in his sister’s house. This girl was treated harshly by her aunt, all work and no rest. When she complained to her father, he lured her by saying that he was taking her on a nice trip. Instead he sold her to a man in exchange for very little money. One day, she met a boy from her past, a childhood friend. She was relieved to see him. He saved her from the man whom she was sold to. But after a few days, this boy also started abusing her. She thought she could no longer bear the sufferings of her life, and so she chose to end it.

'Daughters' - Unknown

I’ve arrived in the form of a daughter into the lives of my parents. This will be my first morning in their house. Why has god made this day as my birth? From today, the day of my arrival into the world, my parents immediately begin talk of my departure. Of my departure from my parents’ house into my husband’s. My parents have given birth to me and raised me, and these parents are the very people who send me away. This is a very strange relationship, parents and daughters, because it seems they raise a daughter just to send her away. This is our fate. The fate of Daughters.

'We Daughters are No Less' - Khuboo Kumari

People believe that the birth of a daughter means a burden to her family. It’s easy to think that having a daughter isn’t a good thing, because girls aren’t like boys, they are burdens, and they are useless. But we are not weak, we are big hearted and kind, and we have much to contribute to the world. Even though we have parents, we daughters are treated like orphans. If we want to be educated, or move forward with our lives our parents don’t help us. All they want is for us to get married quickly, so that the burden we’ve placed on them as girls is removed. In spite of all this, in spite of all the unkindness our parents have shown to us, we daughters are big hearted and kind, and we have much to contribute to the world. By god’s will, everything is changing. Girls have been released from the chains of oppression they were shackled with, and they are moving forward. Nowadays, even parents are proud of their daughters. Indeed they are hopeful for their daughters’ futures. The whole world will witness daughters rising. We daughters are not useless, neither are we burdens. We daughters are big hearted and kind, and we have much to contribute to the world.

'The Girls of Today' - Seem Routh

We are not those who fade once we’ve blossomed. We are not those who take a step back, once we’ve stepped forward. We are those who create our own identity and sense of self. We advance every day with new hope and new enthusiasm. We are determined to finish the challenges we take on. This is who we are: the Girls of today. We know who we are, and we are proud.

Experience Life in India

Now that you’ve seen how girls find identity through their activities, artwork, and poetry, it’s time to create your own! Below, we have featured a variety of crafts, foods, and other activities that will help you experience Indian girls’ lives and traditions.

Baking Chapatis, Claude Renault, 2005. Wiki Commons.

Chapati is a type of flatbread from India, though also common in other countries such as Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. Chapatis are made with a soft dough and cooked on a tava, which is a flat skillet. There is a difference between chapatis and other types of flatbreads, such as naan, due to the cooking technique and type of flour used. Chapatis are usually made with an Indian wheat flour, atta. In some regions of South Asia, the chapatis are also put directly over a flame to puff the bread. The hot air cooks the chapati quickly from the inside, causing it to puff up.

Click here to download our Chapati Activity Guide.

Mehndi Applier, McKa Savage, 2007. WikiCommons.

Mehndi has been practiced in India, Africa, the Middle East, and central Asia for thousands of years. Mehndi as an art was first brought to India in the 12th century by the Mughals, and at first was practiced only by the rich, ruling classes. As more people adopted this practice, the patterns produced became more intricate. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Persian women who were artists and dancers began to decorate their hands with Mehndi. Today, the use of Mehndi has spread around the world, and Mehndi kits which include stencils can now easily be purchased. Its uses are varied, from alleviating blood diseases to providing an emphasis on beauty and coming-of-age for young girls. Mehndi is especially popular during marriage celebrations, with one ritual involving girls and women gathering to help decorate the bride’s hands and feet the night before her wedding.

Bharat Mata Temple Rangoli, Dennis Jarvis, 2007. WikiCommons.

According to a legend recorded in the Chitra Lakshana, Rangoli began when a Chola king and his subjects were grieving over the death of a high priest’s son. Everyone in the kingdom began praying to Brahma, the creator of the universe. Brahma was so moved by all these prayers that he came down to Earth and asked the king to paint a portrait of the dead son on a floor (as this kingdom was known for its floor paintings). Brahma then brought this painting to life, and the kingdom was able to be happy again, and the first Rangoli celebration occurred.

Today, Rangoli is part of the Diwali celebrations, during which geometric patterns and designs are painted at the entrance to the household to invite the goddess Laxmi into the home and drive away evil spirits. It is hoped the goddess will bless the house and stay for a year. Rangoli is also used to give visitors a warm welcome.

Click here to download our Rangoli Activity Guide.

Weaving, Shefshef, 2006. WikiCommons.

Weaving is a type of textile production where threads are interlaced to form fabrics or cloth. Originally girls used to weave primarily for cloth to wear and use at home, but over time it became a practice for the marketplace. Evidence and artifacts of weaving have been found at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, two important cities of the Indus Valley civilization. The ancient Indian texts Rigveda, Mahabharata, and Ramayana also speak about weaving, and one tale refers to a beautiful woven sari worn by the the famous courtesan Amrapali. When the Roman empire was at its peak, India exported so much woven fabric that clothes made from these textiles became trendy among Roman women. Throughout the spread of Islam and rule by the British, weaving continued to evolve by adopting new religious and political significance. Islam discourages representation of living things, so many Indian weaver adopted highly stylized and abstract patterns, including Persian-like florals and fruit imagery. Then, under British rule, Indian weaving became a highly desired commodity and adopted many wallpaper-like scenes for export. These influences combined into the weaving styles we know today. The colors used in weaving have great significance and are known as the “Kinnauri Palette,” which consists of red, yellow, blue, white, and green. In Kinnauri weaving, one color is predominant while the others are used sparingly. Together, these colors symbolize the five elements. When Buddhist motifs are executed in these five colors, they represent a “mystico-spirital core.”

Women’s struggle for equality, recognition, and respect is universal. Tara Books has produced a series of books that collect visual stories by women artists from India that talk about their experiences, dreams, and future aspirations. What unites them is a quiet assertion of their own voice, as they observe and capture the world around them.

Many of their designs have roots in indigenous art traditions, which were used to decorate their homes. Over time, these traditions evolved into distinct art styles, each particular to a region. Each book in this series explores particular themes using distinct regional art styles. The books in this collection are:

- Sita’s Ramayana: A New York Times Bestseller which is a classic Indian epic of Ramayana from the perspective of the captured and banished queen Sita, illustrated in the Patua style.

- Sultana’s Dream: A hundred-year-old utopian novella, imagining an upside-down world where women rule the outside world and men are shut away, illustrated by a Gond artist.

- Hope is a Girl Selling Fruit: A book about a young woman finding her voice, as an artist and as an independent young person, written and illustrated by a young Mithila artist.

- Following My Paintbrush: An autobiography about the incredible journey of Dulari Devi, a domestic helper who went on to become a renowned Mithila artist.

- Drawing from the City: A handmade book about the life of Tejubehan, a migrant worker-turned-artist as she reflects on her journey from poverty into who she is today.

For ways to use this series of books in your classroom, download this Indian Women’s Stories in Art Activity Guide provided by Tara Books, which has talking points and activities to help engage with students both about the stories, the art and the way shows light on the issue of gender inequality.

Educational Guide

Want to use this exhibit in your classroom? Ready to see how much you’ve learned?

Download our Girl Child in India Educational Guide, aligned to U.S. and U.K. curriculum standards. This guide is suitable for middle and high school students, but may be adapted for younger audiences.

Credits

This exhibit was originally produced by Ashley Remer and Junior Girls Sinny Cheung, Emily Holm, Miriam Musco, and Emma Hatherall. Special thanks to Anjali for her creativity and time, and to Lindsey and the girls at Apne Aap.

Revisions undertaken by Vivyanne Collette, Elizabeth Dillenburg, Tiffany Rhoades, and Tia Shah.

Educational activities developed by Hillary Hanel.