This exhibition explores the lives of metis girls who inhabited Fort Michilimackinac, a 17th-to-19th century fort at the Straits of Mackinac in what is now Michigan. The fort was an important center of the fur trade for the French and British colonial empires. Although many people associate the site with male fur traders and soldiers, girls were also present – playing an important role as procurers, providers, and intermediaries. Through their multicultural identity, metis girls forged a path that blurred cultural and gender norms while granting them agency in a time when girls had few such opportunities. Yet their stories have largely remained silent. At Mackinac, they are finally coming to light.

This exhibit is part of our Sites of Girlhood project.

Locating Girlhoods

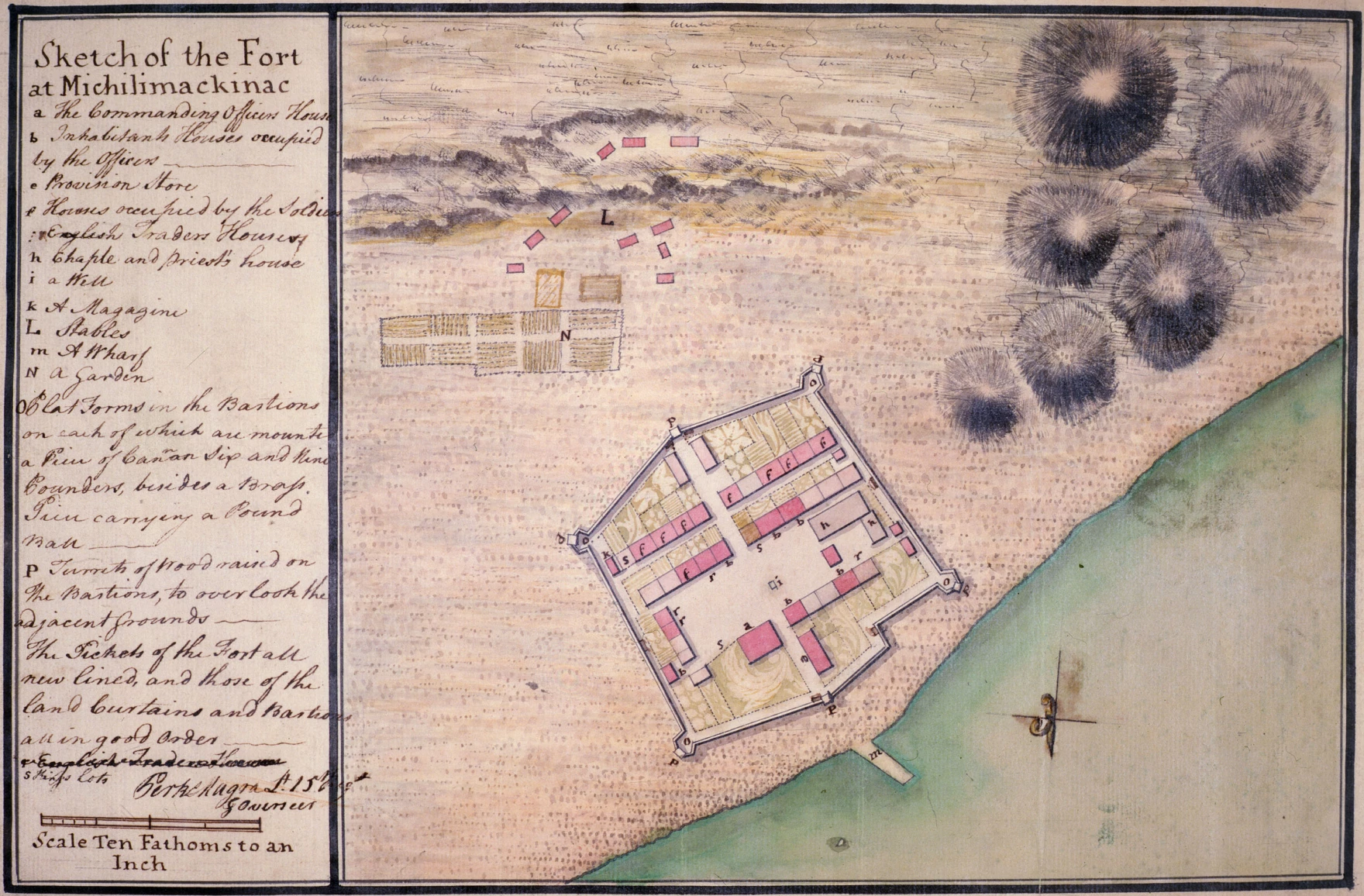

Fort Michilimackinac is an 18th-century fort and fur trading village. Today, the site is a recreation, based on historic maps and over sixty years of archaeological excavations, that portrays life around 1778. Visitors encounter the lifeways of British soldiers, British and French civilians, and Indigenous peoples who lived and traveled through the region. At this time, there were also Black enslaved and free peoples in the region, though their stories are less documented.

For this exhibition, we looked to before 1778 – researching earlier into the region’s history to find evidence of girlhood from the time of French contact with Indigenous peoples up to the American Revolution. We looked at historical and archaeological evidence, including oral histories, to uncover the individual stories of girls and their families. Most times, we simply found names.

Of the stories found so far, all of the girls were metis – defined as being of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry, particularly related to French Canada. Their stories reveal the complexity of colonial interactions along the “frontier” – a border zone where French, British, Black, and Indigenous peoples negotiated shifting identities, lifeways, and sociopolitical alliances. Within this zone, metis girls negotiated their own identities and forged their own unique lives. Though evidence is fragmentary, this exhibition is a step towards piecing together their complicated, yet fascinating, roles in Indigenous, American, and Canadian history.

Cradleboard cover, collected between 1790 and 1795 by British Army officer Major Andrew Foster (1768-1806) at Fort Miami or Fort Michilimackinac. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian. Used under Educational Fair Use conditions.

Where is Fort Michilimackinac?

This video discusses the history of Fort Michilimackinac. To date, archaeological evidence has dated the earliest iteration of the fort to 1715, built by French captain Marchand de Lignery.

Geographically isolated, the community was heterogenous. These cultural groups forged alliances and a community that largely respected their differences of ritual, belief, and practice; they gathered, grew, traded, processed, packed, and shipped natural resources to the colonies and beyond, becoming an important trading center and access point to the western portion of what would become the United States and Canada.

Who inhabited the fort?

Several cultural groups inhabited the area around and occupied by Fort Michilimackinac – called the “Straits of Mackinac.” This is because of the geography – the area features narrow waterways where two of the Great Lakes – Lake Huron and Lake Michigan – meet. Like highways today, this provided an important place for traders and travelers to go from one lake to another, and provided an easy place to rest and meet others. Prior to Europeans’ arrival, the area was home to Indigenous peoples including the Anishinaabek (Anishnabeg), Ojibwe (Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa), and Potawatomi.

Europeans first visited the area in 1641, but they did not settle there until 1671 when the Jesuit St. Ignace Mission was built by the French.The mission closed in 1701, when the French moved to Detroit. Twelve years later, Fort Michilimackinac was established and took two years to fully complete and garrison by the French. For 45 years, it served as the center of French influence in the region and was a main center of the French fur trade.

French settlers…

- Depend more on fish and wild game.

- Prefer corn from Ottawa and Chippewa women.

- Build houses in a poteaux-en-terre style

- Are Catholic

- Have norms where girls spend more time with their mothers, so mixed heritage girls tend to retain Indigenous language and folkways

Fish Skeleton found by archaeologists at Fort Michilimackinac. Courtesy Mackinac Parks.

In 1761, Fort Michilimackinac was relinquished to the British following the French’s defeat in the French and Indian War. The British continued operating it as a trading post, but most residents remained French and Metis (Ojibwe-French), and they did not welcome British rule. It was not until after Pontiac’s War and the fort’s rebuilding on Mackinac Island that more British moved into the Fort.

With the British presence came…

- Paranoia of Indigenous unrest and rebellion

- Fort was dismantled and moved to nearby Mackinac Island from 1779 to 1781, which separated the fort from village life and disrupted historic French construction and lifeways

In 1783, the fort was given to the United States as part of the Treaty of Paris (Britain’s surrender at the end of the American Revolution). Though now considered American, most residents maintain their multicultural identities rather than assume a new “American” identity. Additionally, although many Indigenous populations are forcibly displaced in other parts of the United States, they are not displaced from the fort or surrounding regions.

By this time, metis was an identity more important than any other…

- Resulted from mixed ancestry, typically Indigenous and French Canadian

- Typically spoke French

- Acted as intermediaries between Indigenous and European communities, even in political and military life

- Role as intermediary could supercede gender norms

1765 plan of Fort Michilimackinac. Buildings inside the fort are labeled as either being occupied by civilians or military personnel. External stables and outbuildings are shown to the south of the fort. Perkins Magra, Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

What about Black girls?

Throughout the French, British, and American periods, Black girls were present at the fort. Many were brought through capture during raids of Southern slave plantations, had been sold or traded to the French, or came enslaved by masters who had migrated to the fort. The largest group of slave owners were the fur trappers, who viewed slaves as their companions, depending upon them for survival and friendship more than just labor.

Notably, the French permitted and encouraged manumission, and French Catholicism gave enslaved Blacks rights to education, baptism, sacraments, and marriage. French law allowed Blacks to as witnesses in religious ceremonies and petition for their liberty in court. When the British took over, terms of the fort’s transfer included maintaining these customs. After manumission, many formerly enslaved Blacks stayed near the fort, becoming part of the community.

The first identifiable Black girl in the registers of St. Anne’s Catholic Church at Fort Michilimackinac is Veronique, baptized on January 19, 1743. She is listed as the daughter of Bon Coeur (Good-Hearted) and Marguerite, both enslaved Blacks belonging to Sieur Boutin, a trader wintering at the fort.

Another notable identity found in the registers is that of the Bonga family: Jean and his wife, Marie-Jeanette, and their two young children, 4-year-old Etienne and 3-year-old Pierre. In 1778, they were among the enslaved Blacks captured by the British in St. Louis (then a Spanish city) and taken to Fort Michilimackinac. Jean, Marie-Jeanette, Etienne, and Pierre were given to Captain Daniel Robertson. During their enslavement, Marie-Jeanette gave birth to Rosalie (1780) and Charlotte (1786). Captain Roberston eventually freed the Bonga family. They made their home at the fort, opening the first hotel and tavern on the island.

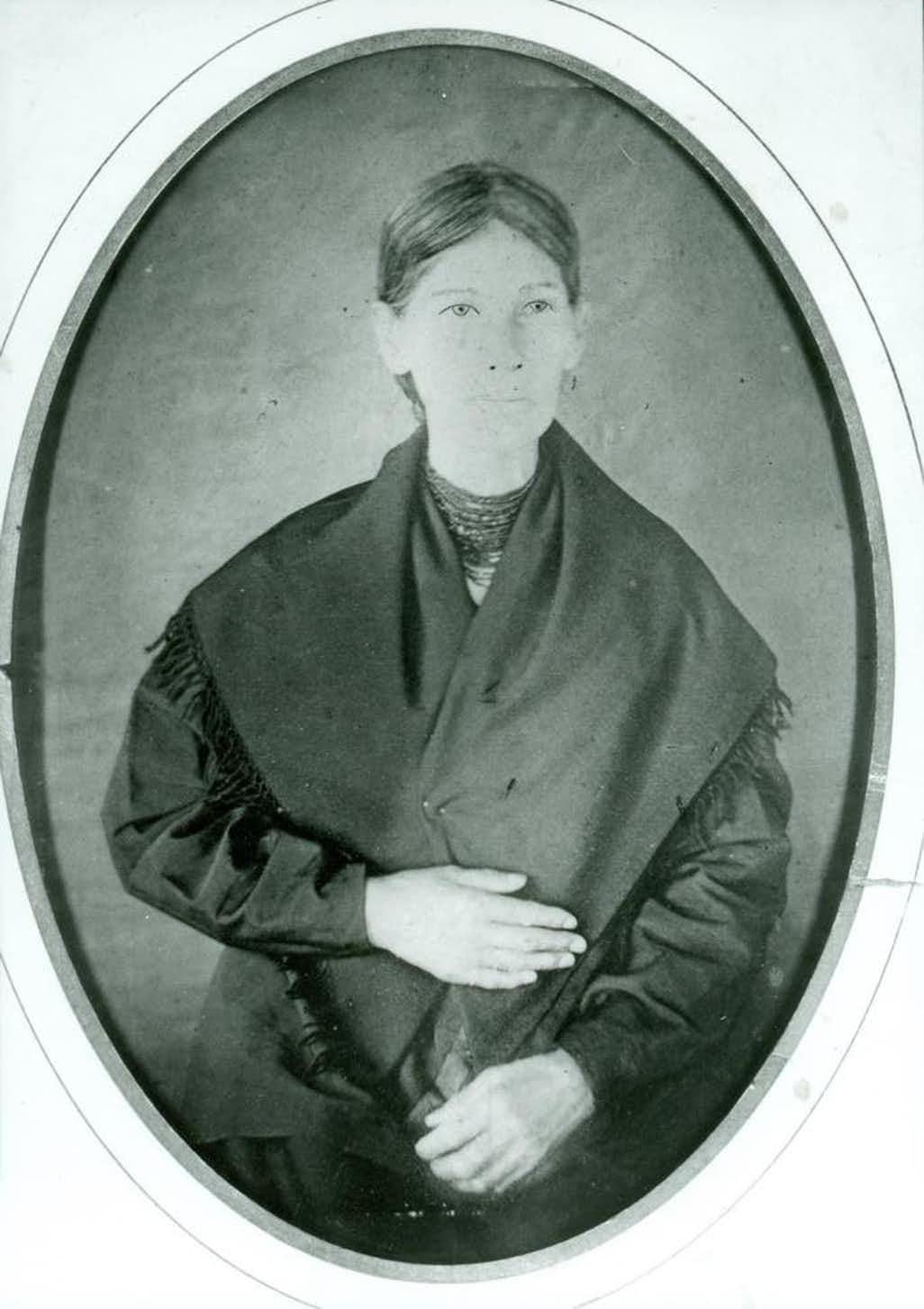

The first Bonga girl whose portrait we have is Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom (c. 1797 – February 6, 1880), granddaughter of Jean and Marie-Jeanette and daughter of Pierre. This circa 1823 photo, taken upon her marriage, is the only known photo of Margaret. She never lived at Fort Michilimakinac, but may have visited. Courtesy Wikipedia.

How do we find girlhood at the Fort?

Women and girls lived at Fort Michilimackinac. Some of their names are recorded in fort records, while others are known to us through oral histories or archaeological evidence. Their activities were documented by fort officials and in journals, and included making birch-bark canoes, cloth and clothing; supervising production for farms; housekeeping; baking and laundry; and assisting with gathering, growing, trading, processing, and packing natural resources.

Archaeological evidence includes bone tools and birch-bark containers used by Ojibwe women. These support church records from the fort, which recorded the marriages of Ojibwe women to French fur traders. Though Indigenous women’s lives are often silenced in written records, these small fragments provide important clues to their presence at Fort Michilimackinac.

For example, most fishing was done with nets because it was the most efficient method, but lines and spears were used as well. Archaeologists have found evidence of all three methods, including bone harpoons that would be attached to spears. Indigenous peoples made most of the bone tools found at the fort, and taught these skills to their métis children. The métis became the backbone of the fur trade.

Bone harpoon tip found at the fort. Courtesy Mackinac State Historic Parks, MS2.11028.39

Colorful glass beads of all kinds were popular trade items. Most were manufactured in Venice. Courtesy Mackinac State Historic Parks, MS2.8765.38, MS2.9390.4, MS2.8474.4, MS2.10333.2

Otter or beaver effigy, possibly a toy. Courtesy Mackinac State Historic Parks. MS2.6702.25

Engraved metal with “Jane”. Unknown use. Courtesy Mackinac State Historic Parks. MS2.4266.1

Identifying Girls

Historians and archaeologists also use written records, including maps, military correspondence, supply lists, and fur-trade records. One key record utilized in this exhibition was Baptismal Records from the parish of Michilimackinac. From 1712 to 1741, the records listed the baptisms of “daughters” and “slaves” who were identifiably young girls. (See toggles below.)

Daughters

- Domitille Villeneuve, September 27, 1712

- Anne l’Anglade-Villeneuve, March 8, 1716

- Agathe l’Anglade-Villeneuve, February 5, 1724

- Marie (Manon) Chevalier, October 12, 1724

- Marie Ursule Amiot, October 29, 1724

- Judith Reaume, June 27, 1725

- Anne Charlotte Veronique Nannette Chevalier, March 1, 1726

- Anne Domitille Nanette Parent, April 22, 1726

- Catherine Angelique Vieu, June 5, 1726

- Charlotte Parent, October 1, 1729

- Anne Therese Esther Chevalier, March 28, 1732

- Mary Louise Amiot, March 20, 1732

- Angelique Chevalier, July 11, 1733

- Marie Anne Blondeau, October 16, 1733

- Marie Ester l’Arche, January 1, 1734

- Marie Anne Amiot, April 5, 1734

- Marie Catherine des Hetres, September 19, 1734

- Marie Anne Parent, November 26, 1736

- Francois Michelle du Lignon, September 29, 1737

- Francoise Veronique Rocheveau, April 29, 1738

- Marianne Hamelin, November 26, 1738

- Ursule Amiot, December 27, 1738

- Anne Mendard, July 13, 1739

- Therese de Lignon, July 14, 1739

- Angelique du Lignon, June 4, 1740

- Anne Josephe Parent, June 4, 1740

- Marie Francoise Hamelin, October 2, 1740

Slaves

Of the nine baptismal records designated “slave,” 4 are identifiably young girls:

- Marie Madelein, 4 yo slave of Mr. l’Angladem 1735

- Marianne, 20 yo lawful wife of Jean Baptiste, formerly a slave, 1737

- Marie, born of a slave of Sieur Chevalier, 1737

- Marie Madeleine, 5 or 6 yo slave of Sieur C. Gautier, 1741

Finally, we rely on the work of other scholars. Research is not done in a vacuum. Historians and archaeologists rely on one another to fill in the gaps, and interpretation specialists at Fort Michilimackinac take this work and create public programming to help us understand life at the fort. One such interpretive method is the Fort’s current YouTube channel, which provided a variety of video content to help showcase life at the fort in the 1770s, while another are conference presentations by students and faculty who conduct research on the fort and its inhabitants.

Women’s Clothing at Colonial Michilimackinac

by Mackinac State Historic Parks

Getting ready for the day in the 18th Century was a bit different from what we are used to today. Historic Interpreter LeeAnn shows us the stepsby-step of getting dressed for a lady at Colonial Michilimackinac in the 1770s.

The Power of 18th Century Indigenous Women

by Kristina Sweet

Reconstructing the life of Marie Madeleine Réaume L’Archevêque Chevalier (1711-1784) and her use of different social spaces, Sweet examines how Native women understood space and social relationships with Euro-American men and Indigenous men.

Girls of Mackinac

Couc Sisters

Madeleine and Elizabeth Couc were sisters who married Europeans. According to a parish record of Elizabeth’s marriage later published in the History of Sorel, their father was a French soldier and their mother an Indigenous (“algonquine”) woman.

Madeline married French interpreter Maurice Menard in 1692, bearing their first child three years later. She is believed to have died in the 1760s at Fort Michilimackinac. Elizabeth married German voyaguer Joachim Germano on April 30, 1684. Very little is known about their actual lives.

Veronique

Baptized at Mackinac on January 19, 1743, very little is known of Veronique – the daughter of enslaved individuals named Bon Coeur and Marguerite. The family was owned by voyageur Sieur Boutin, who was wintering at Michilimackinac on his way to Illinois. Slavery was permitted in the colony under French decree, and Veronique is the first black slave to be clearly identified at the fort.

Under the French, slaves typically performed domestic chores or assisted with the fur trade. However, unlike British slavery, the French system had a provision where slaves could be freed at any time. Like the Bongo family, if Veronique’s family was freed, they likely remained part of the frontier community. Unfortunately, Boutin left in the spring of 1744, and we do not have records indicating the fate of Veronique and her parents.

Elizabeth Mitchell

Elizabeth Mitchell (ca. 1760 – 1827) was of Ojibwa and French descent and became a well-known fur trader at Michilimackinac. During the summer months, she resided at the fort and visited daily with the local Indigenous peoples, acting as an intermediary and conducting her trade. In the winter, she typically resided with the Ojibwa (or possibly the Odawa, given that her mother remarried into that tribe) and participated in the mainland hunting grounds and the hunting traditions of her Indigenous kin.

When the British took over the fort from the French, Elizabeth continued her fur trade. She married a British soldier, Deputy Commissioner David Mitchell, in 1776. The couple erected a house on Market Street at Fort Michilimackinac and soon became one of the wealthiest families at the fort. They also played a major role in defending the fort during the War of 1812, as Elizabeth rallied Indigenous fighters to defeat American troops in the region. The British were so grateful that they directly paid Elizabeth 100 pounds.

After the fort came into American control, Elizabeth became a target because of her marriage, British military aid, and commercial success. The U.S. Indian Agent Henry Puthuff painted her as “consorting with the enemy” because of her marriage to a British citizen. In 1815, Elizabeth was charged with treason and, to avoid jail, she left Mackinac for Drummond Island, Canada. She died in 1827.

Marguerite-Magdelaine Marcot

Born to an Odawa mother and French father around 1780, Marguerite-Magdelaine grew up in the Grand River Valley with her mother’s community after her father died in 1783. She was baptized Roman Catholic at Michilimackinac and learned Odawa, French, English, and Ojibee. At age 14, she married French fur trader Joseph La Framboise by Odawa custom. She remained in Grand River, working with her husband to develop the fur trade and establish trading posts between the Odawa and Mackinac Island, including the Fallasburg post – the first permanent mercantile building in west Michigan.

In 1804, Magdelaine’s life changed dramatically: her marriage was solemnized by a missionary priest at Michilimackinac, making it officially French-Odawa in church records. This allowed the families to become legal kin and established official trading partnerships sanctioned with business licenses. This was crucial when, two years later, Magdelaine’s husband was murdered.

After a winter in mourning, Magdelaine emerged as an independent trader: she never remarried, but her legal status as French-Catholic kin and social prominence as a young Odawa woman (still in her twenties) allowed her to take over the business. At a time when successful fur traders earned about $1,000 per year, Magedeline earned between $5,000 to $10,000. For the next fifteen years, Magdelaine traded between the Grand River valley Odawa and Michilimackinac, becoming known as Madame La Framboise, with licenses from the British, French, and Americans. In 1822, she sold her company and retired to Mackinac Island, where she died in 1846.

Agatha de la LeVigne Biddle

Born in 1804, Agatha de la LeVigne was a Metis girl of Odawa, Ojibwe, and French descent. Described as “beautiful” and “fair,” she married wealthy Philadelphian fur trader Edward Biddle in 1819 in the “event of the season.” Donning a traditional Odawa outift – a skirt of ribbons and beads, leggins, a silk blouse with fitted sleeves, and necklaces – Agatha established her married life wearing traditional Odawa clothing while at Biddle’s house on Mackinac. The couple had three children.

As partners, Agatha and Edward ran an independent fur trading business. Agatha set the prices, negotiated with fur traders, and hosted functions in their home. She was also known to care for the island’s orphans and sick, and served as the island’s undertaker by supplying coffins and providing burial services. She also used birch bark to engage in quill work and basketry. In the mid-1800s, Agatha was made chief of the Mackinac band.

Agatha and Edward’s home still stands, fully restored, on Mackinac Island today. The home’s interpretation focuses on Agatha’s life and work, including the tragic death of her eight-year-old daughter, Mary, whose grave is the oldest in the St. Ann cemetery.

Courtesy Mackinac State Historic Parks Agatha Biddle, who was of mixed heritage—part French, Odawa and Ojibwe—was born on Mackinac Island and identified as Odawa.

Elizabeth Fisher Baird

Born in 1810, Elizabeth was the daughter of an Odawa woman and Scottish trader who grew up at Mackinac. Her mother ran a boarding school for traders’ daughters, where they learned to read, write, and sew along with general housekeeping skills. She was also the great-niece of Marguerite-Magdeline Marcot.

What makes Elizabeth’s story unique is that we have her own recollections, which describe not only her girlhood but also things like the weather, sugar camps, and relationships. From these, we learn that relationships among the tribes were complex:

Individually, I feared all Indians except our own – Ottawas and Chippewas. My dislike for other tribes was an inheritance.

We also learn about life at Mackinac during the winter. Elizabeth remembered wearing long circular cloaks of snuff-brown broadcloth, a beaver fur cap, moccasins, and buckskin, fur-lined mittens. In fact, winter was Elizabeth’s favorite season:

I was particularly fond of the Island of Mackinac in winter, with its ice-bound shore. In some seasons, ice mountains loomed up, picturesque and color-enticing, in every direction. At other seasons, the ice would be as smooth as one could wish. There was hardly any winter communication with the outer world; for about eight months in the year, the island lay dormant. A mail would come across the ice from the mainland, once a month, to disturb the peace of the inhabitants; its arrival was a matter of profound and agitating interest.

During the summer months, Elizabeth’s family traveled to the maple sugar camps of the Northwest. She particularly remembered traveling to her grandmother’s camp on Bois Blanc Island, five miles east of Mackinac:

About the first of March, nearly half of the inhabitants of our town, as well as many from the garrison, would move to Bois Blanc to prepare for the work. Our camp was delightfully situated in the midst of a forest of maple, or a maple grove. A thousand or more trees claimed our care, and three men and two women were employed to do the work. The ‘camp’,–as we specifically styled the building in which the sugar was made, and the sugar-makers housed,–was made of poles or small trees, enclosed with sheets of cedar bark, and was about thirty feet long by eighteen feet wide.

In 1824, at the age of 14, Elizabeth married Henry Baird – an Irish immigrant who was working as a teacher on the island. The couple moved to Green Bay the next month, where Henry became the first lawyer in what is now Wisconsin. In Green Bay, Elizabeth taught herself English and became an interpreter for Henry’s French-speaking clients before taking over management of the family farm while raising their four daughters. In the 1880s, Elizabeth published her autobiography – first in the Green Bay State Gazette and later as two books called Reminiscences of Early Life on Mackinac Island and Reminiscences of Life in Territorial Wisconsin. She died in 1890.

Legacy

Metis girls demonstrate a unique way of life that combats traditional notions of an isolated, homogenous frontier where Europeans faced off against Indigenous peoples and the wilderness. Their lives at Michilimackinac present a multicultural society where individuals were interdependent on one another, learned from one another, and formed a community that ebbed and flowed with the seasons and thrived upon trade and communication.

“Over time, intermarriage produced an increasing number of bi- and multicultural descendants, many of whom grew to maturity in Indian communities. By the time Britain wrested sovereignty…a network of interrelated, mixed-ancestry families had evolved that controlled much of the Great Lakes fur trade. Relatedness was a primary determinant of power, and nationality remained immaterial…”

– S. Sleeper-Smith, Unpleasant Transaction, p. 417-418

Pair of cut-out silver earrings collected between 1790 and 1795 by British Army officer Major Andrew Foster (1768-1806) at Fort Miami or Fort Michilimackinac. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian. Used under Educational Fair Use.

What happened after 1800?

Let’s explore the life of two metis girls to find out.

Rosalie Laborde Dousman was born at Fort Michilimackinac on February 1, 1796. Her mother, Marguerite Chevalier, was Ojibwe-French, and her father, Jean Baptiste LaBorde, was a German-American ship pilot. At age ten, Rosalie was sent to a convent school in Trois-Rivieres, Canada, where she spent two years. She returned to the fort in March of 1808 and married John Dousman, a 22-year-old fur trader. Two years later, at age fourteen, she moved with John to Green Bay and settled along the Fox River. Rosalie had her first child at age sixteen. Shortly after the birth, Native Americans attacked their home during the War of 1812, forcing John, Rosalie, and their daughter to return to Fort Michilimackinac for safety. John enlisted to serve in the war, and afterwards became a sutler at the fort. The couple had seven children. Later in life, they returned to Green Bay, where Rosalie became head of a school for Menominee children. She was so well-known for her work that the Pope sent her his own rosary. Rosalie died in 1872.

Rosalie’s story is one example of metis girls’ lives at Fort Michilimackinac. Like many girls in this exhibition, her story overlapped with various cultures and was shaped by influences beyond her control – such as the continuing frontier warfare from the American Revolution and its culmination in the War of 1812. Yet by the 1800s, Rosalie’s role as a metis girl was waning. She was no longer needed as an intermediary. Instead, her Indigenous heritage was largely being pushed out of her life. From what we know, it appears that Rosalie embraced her European heritage – at least enough that Indigenous peoples attacked her home and that, later, she would help foster the Christianization of Indigenous peoples (the Menominee) by heading a school.

As Fort Michilimackinac waned after the War of 1812, so did the role of metis girls like Rosalie. American policies towards Indigenous peoples – especially the Indian Removal Acts and forced education at mission schools – sought to erase Indigenous lifeways. The fur trade was also waning as the beginnings of the industrial revolution, railroad systems, and westward expansion led to less reliance on Indigenous peoples.

The world was changing, but metis girls and their skillsets were changing with it. One such girl was Marguerite Bonga Fahlstrom – the granddaughter of Jean and Marie-Jeanne Bonga (enslaved Blacks on Mackinac in the 1780s, whom we met earlier). Jean and Marie’s son, Pierre, had left Mackinac to become a successful fur trader near Lake Superior. Pierre had married an Ojibwe woman, Ojibwayquay, and the couple raised their children in a multicultural environment.

Marguerite (possibly known as Kahjiji in Ojibwe) was born in 1797, and her family maintained ties with their Bonga and Ojibwe relatives while also raising the children as Catholic. In the 1820 account of Henry Schoolcraft, who visited the family at Fond du Lac, Marguerite was noted as being “black” as her father with “curled hair and glossy skin of the native African”.

In 1823, at age 26, Marguerite married Swedish fur trader Jacob Fahlstrom. The couple and their children lived near Fort Snelling, where Margaret and her children were in proximity to 15 to 30 enslaved African Americans as well as several Dakota, Ojibwe, and metis women. The family were relatively poor, with the local agent noting that they lived “without a stove, candles, an ice house, or more important, regular supplies of goods from the St. Louis markets.” The family lived at Fort Snelling until 1840, when they were evicted under the land cession treaties. Over the next 20 years, Jacob became a famous Methodist missionary, with his fluency and family ties (through Marguerite) noted as part of his success. Marguerite stayed in Washington County, Minnesota, mangaging the family’s new home and keeping open house for traveling Methodist clergymen.

Despite all her hardships, Marguerite visited Manitou Island each spring to make maple sugar until her death in 1880. Maintaining this Ojibwe tradition, Marguerite passed on Indigenous practices that had been sustained her maternal ancestors for centuries while witnessing the transformation of metis women’s power from equal or independent partners into those dispossessed by their government and forced to remain hidden by their husbands’ careers.

While Rosalie was becoming more European, Marguerite was becoming marginalized. Like many women of the 1800s, Marguerite’s skills and achievements were pushed into the background of her husband’s life, contextualized to be in service to him rather than given a stage of her own. This marginalization almost meant historical erasure. In recent years, historians have worked to recover Marguerite’s story and reveal the layers of racial, ethnic, religious, settler, and gender complexities that her story can help us understand.

Daguerrotype of Marguerite Bonga Fahlström & Jacob Fahlström, 1823. Courtesy Wikimedia / Historic Fort Snelling.

Credits

Special thanks to the curatorial team, Maria “Ria” Smith, Tiffany Isselhardt, and Brittany Hill, and to our editor, Katie Weidmann. Also thanks to the team at Fort Michilimackinac, and to all the archaeologists and scholars – past and present – whose work contributes to our understanding of this region and the many people who have inhabited it.

Bibliography

The following sources were utilized in creating this exhibition:

Allen, Anne Beiser. “A Bridge Between Cultures: Rosalie Laborde Dousman’s Indian School.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 94.1 (2010): 14–25.

Baird, Elizabeth Therese. “Reminiscences of Early Days on Mackinac Island.” Library of Congress.

Eyre, Sally. “Dirt Detectives.”Cobblestone 19:8 (Nov. 1998), 34-39.

Dunnigan, James Cain, “Those Beyond the Walls: An Archaeological Examination of Michilimackinac’s Extramural Domestic Settlement, 1760-1781” (2020). Master’s Theses. 5157. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/5157

Karahasan, Devrim. “Metissage in New France: Frenchification, Mixed Marriages and Metis as Shaped by Social and Political Agents and Institutions 1508-1886” (2006). Doctoral Dissertation. European University Institute Dept. of History and Civilization.

Katzman, D. M. (1970). Black Slavery in Michigan. American Studies, 11(2), 56–66.

Littlejohn, E. J. (2018). Black Before the Bar: History of slavery, race laws, and cases in Detroit and Michigan. Journal of Law in Society, 18(1), [ix]-[vi].

Magnaghi, Russell. “Black Americans in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula – Part One,” Rural Insights (January 15, 2021). https://ruralinsights.org/content/black-americans-in-michigans-upper-peninsula-part-one/

Magnaghi, Russell M. “Native American and French Settlement Patterns at St. Ignace, Michigan, 1670-1715.” (Study at request of St. Ignace Downtown Development Agency, 1989).

Noel, J. (2006). “Nagging Wife” Revisited: Women and the Fur Trade in New France.” French Colonial History 7, 45-60. doi:10.1353/fch.2006.0009.

Phillips, Ruth B. “Reading and Writing between the Lines: Soldiers, Curiosities, and Indigenous Art Histories.” Winterthur Portfolio 45, 107-123.

Scott, E. (1991). “A Feminist Approach to Historical Archaeology: Eighteenth-Century Fur Trade Society at Michilimackinac.” Historical Archaeology, 25(4), 42-53.

Sleeper-Smith, S. (2000). “Women, Kin, and Catholicism: New Perspectives on the Fur Trade.” Ethnohistory 47(2), 423-452.

Sleeper-Smith, S. (2005). “[A]n Unpleasant Transaction on This Frontier”: Challenging Female Autonomy and Authority at Michilimackinac. Journal of the Early Republic, 25(3), 417-443.

Smith, Donald B. (1996, Aug 21). Toronto’s first murder followed a clash of cultures: [final edition]. Toronto Star.

Widder, Keith R. “Persistence of French-Canadian Ways at Mackinac after 1760” Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society, 1992, Vol. 16, p45-56.