The relationship between girls and advertisements for consumer products has a long and ambiguous history. Used as both the models within ads as well as the target audience for them, girls play a large part in the advertising industry. What do these advertisements say about girlhood, gender roles, and other identities?

In our first student-led collaboration, Girl Museum partnered with Dr. Emilie Zaslow and her Spring 2023 “Girls’ Media Studies” class at Pace University. To examine the representation of girls in media, her students selected and analyzed advertisements from the 1910s to 1960s. With guidance from the Girl Museum team, students were introduced to methods of interpretation for virtual museum audiences. They chose advertisements, conducted research, and wrote the interpretations seen below. We are thrilled to showcase these emerging girl studies scholars and their work.

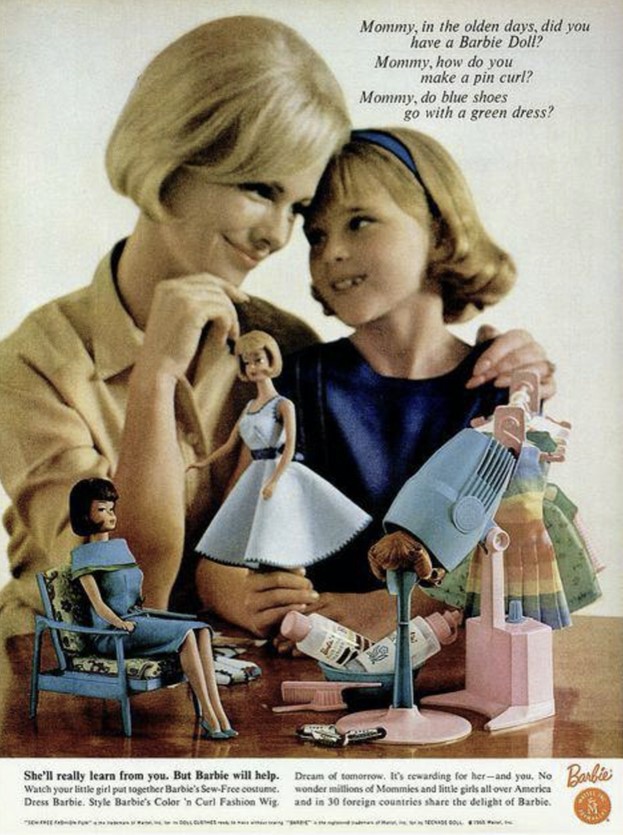

This ad promoting Barbie, created in 1965, is a great example of presenting the social norms and standards for girls in the 60s. The ad depicts a young girl playing with dolls alongside her mother. At the bottom of the image it says, “She’ll really learn from you. But Barbie will help.” The daughter and mother, who look very similar, gaze into each other’s eyes as they play with the dolls. The quotes at the top of the ad (“Mommy, did you have a Barbie doll?… How you make a pin curl?… Do blue shoes go with a green dress?”) tell the reader that the daughter is asking her mother about play, beauty routines, and fashion.

The ad suggests to girls that they will one day live a life like these dolls and their mothers, focused on clothes, hair, and makeup. This girl is not depicted as getting dirty, playing outside or being more rebellious. Gender has always been used to divide us as a society, and toys greatly impact how kids grow into themselves, as they are being taught this so young.

Barbies, along with many other “girl toys” show extreme sexism that was normalized at the time, making it have a big impact on the way children think and act. This is an issue as it gives children no space to discover individuality nor to grow into who they want to be rather than who they have to be.

– Eliza Rafter

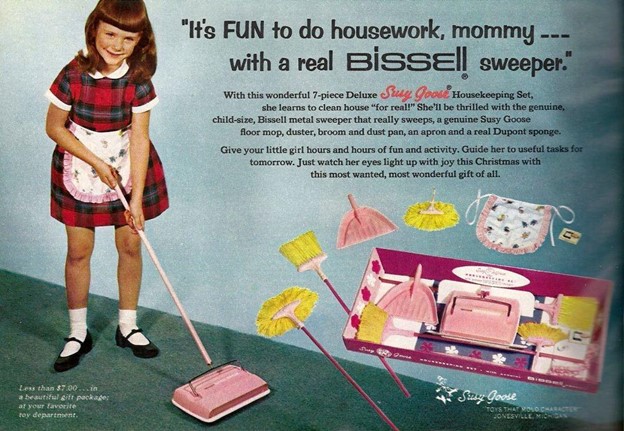

Throughout the Victorian Era, young girls were expected to grow up very quickly, thus introducing the idea of “little women.” This ‘Susy Goose Housekeeping Set’ advertisement was showcased on the cover of Woman’s Day magazine in December 1965, just in time for Christmas. Depicted is a young girl shown wearing a dress with a pink apron, modelling an entirely pink toy cleaning set. Associating color with gender has been extremely common for decades, generally with pink assigned to girls and blue to boys. During this time, despite a burgeoning feminist movement, housework and cleaning were still considered chores to be completed by women and girls.

Thankfully, in 2023, society has come much further from this mindset. Still, in this very day, there are media messages, like this advertisement, that may seem small or inconsequential that lead to increased misogyny and strengthening of the patriarchal system embroidered in society. This advertisement is detrimental in that it played a role in instilling the thought that a woman’s purpose is to stay home and care for the household, while the man of the house is to go out and work to bring back income. Ads like this subtly support the idea that women need to rely on men for finances, which creates great power in men’s social and economic positions. Though this advertisement seems harmless initially; however, it is based on a harmful, antiquated idea.

– Natalie Estrella

Buddy L was a toy company that began its business creating miniature replica cars from American steel for young boys to play with and learn from. After all, young boys often looked up to their fathers and the men in their lives who had such cars. But in May of 1969, Buddy L decided to dive into the world of young female interest to create a line of toys. The company wanted to bring the same quality and experience to young girls. So, they created their first product targeted at the young female market: a mini kitchen.

Even as the rise of second-wave feminism was underway, this ad emphasizes and blatantly displays the stereotypical gender roles of the 1960s. The ad’s imagery shows both children smiling widely with their toys, with the boy’s hand in motion as he rolls the car and the girl’s hand in action as she grabs a kitchen appliance. The imagery is so simple in its inequality, as the girl is portrayed as extremely happy to play with her toy kitchen. Her smile encourages other young girls to want to do the same.

This toy release was seen as usual and appropriate in the 1960s, but in analyzing it now, it feels ludicrous. Buddy L, as a company, is trying to open up its customer base. In doing so, it actually cuts itself off from a whole group of children who could have enjoyed its products. They purposely chose to market their new line of kitchenware/homemaking toys to young girls, as these were the stereotypical interests of their age group at the time. Stereotypical, not because the mass majority of young females enjoyed the activities of keeping a home, but because these were the interests allowed of girls.

Buddy L clearly states in their advertisement that their quality is now present in “…both girls’ and boys’ toys!” when in reality, they placed expectations on both girls and boys that are not of quality. Assuming that young girls would only be interested in “…appliance[s] [with] action feature[s] built-in…” while boys could only be interested in cars that “…really steer too!” is their vital error in marketing.

– Chloe Fuller

In this vintage toy ad from 1959, viewers are introduced to Chatty Cathy, a doll for young girls that spoke when the string on her back was pulled. Using a feminist approach, as well as gender schema theory, one can see the misogynistic connotations of this ad and its purpose of teaching young girls their place in society.

Gender schema theory is the idea that people’s perceptions, memories, and interpretations about gender are influenced by their culture. Children are especially susceptible to the influence of media since they are learning about the roles they are expected to play in society—more specifically, they learn which gender roles they are expected to play. The name and phrase “Chatty Cathy” has misogynistic connotations; it complies with the idea that women talk too much. Many girls have been called “Chatty Cathy” since the doll’s release, simply for going “off-script” and voicing opinions.

Another thing that both the ad and the dolls reinforce is the idea that whiteness is centered and other races or identities are inferior. When there are no other options for skin tone, young girls of color may feel uncomfortable in their skin because they do not see girls that look like them being represented. These dolls also represent a privileged girlhood, since they have the luxury of only wanting to play games and change outfits all the time. This may also make less privileged girls feel inferior.

Cathy says things like “Let’s play house,” and “Can you change my dress?” These phrases are subtle yet aimed to teach girls what they should care about: being good homemakers and looking pretty—nothing more and nothing less.

– Makenzie Novak

The largest image in this 1944 ad for “Girls in Uniform” doll is of a white woman with blonde hair who is actively saluting. The other images of women in this ad are on the cover of the box of dolls which is featured in the ad’s center. These women, all white, thin, and coiffed fit into the category of what was, unfortunately, one of the only images of womanhood that the economy in America 1944 represented.

The ad states, “O beautiful junior girls in uniform” and guarantees retailers that the toy is “packed with eye appeal.” This is fascinating because the ad is validating how a woman looks but not what she is capable of. At the same time, these dolls are in WACS and WAVES uniforms. These organizations created an opportunity for women to assist during WWII, via intelligence, critical jobs, mechanics, and much more. This ad is intentionally showing girls that they can assume an important role in America that was not available to them before.

While this ad is targeted to empower women and girls, it also focuses on the vanity of feminine representation in capitalism, by having the girls in heels, skirts, makeup, and tidy hair. All in all, the wording and representation in this ad excludes all girls with different body types, or races. This proves to be an ingenuine attempt at empowering ALL girls.

– Cali Snyder

The Little Cooks and Hostesses catalog page from the 1950s advertises toys for young girls that emulate the appliances that can be found right in their own kitchens. From tea sets to cookware and from real working electric ovens and stoves to pre-approved recipes, young girls were being trained to start preparing for tasks related to motherhood from a young age. Prior to the second wave of the feminist movement, the mother was expected to prepare meals and host various events for family and friends. The house was one of the only areas where a mother had power and could control what events and activities took place.

Little girls during this time helped their mothers with everyday kitchen tasks, whether it was setting the table or washing the dishes; young girls were familiar with the work their mothers did and already knew how to do some of it on their own. Therefore, creating a set of toys depicting the specific work that young girls perform every day, will allow them to practice for the future in which they will do it on their own, once married with their own children in their own house.

Furthermore, the advertisement being entirely pink, containing pink dishware and appliances, and showing girls in the advertisement wearing frilly dresses, continued to enforce gender norms such as color association amongst boys and girls, and fashion considered suitable for young women.

Overall, the consistent theme amongst children’s toys during this time period was that they prepare kids for a future associated with their gender; they familiarized them with what they would be expected to do once they were adults. Young girls were being prepared to be, as the title of the advertisement states, “cooks and hostesses.”

– Stefanie Giacoumopoulos

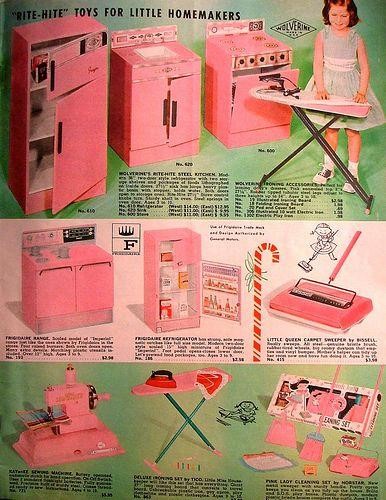

Young girls, especially in more traditional societies, have always had gendered norms communicated to them, whether subconsciously or intentionally, by parents and media. “Toys For Little Homemakers” by Rite-Hite is a prime example of this as it displays various cues communicated to girls about society and their expectations for girlhood and womanhood.

Firstly, traditional norms of gender are represented by having each item of the toys being shades of pink, representing that these “toys for little homemakers” are intended for young female-presenting children. Following up on that, not only are the toys pink, but the ad itself only shows a young girl using the toys, along with a cartoon girl-like figure throughout and a girl on the cover of the box (located in the bottom right corner).

Secondly, marketing these toys as “toys for little homemakers” communicates to young women the traditional societal expectation that girls were meant to be homemakers. To be society’s traditional “homemakers,” girls/women must be well versed in cooking, cleaning, and other household duties, clearly represented here by the toy ironing board, sewing machine, broom set, and play stove.

Furthermore, even the product names, including “Little Queen Carpet Sweeper” for the toy vacuum, display various cues to young children, specifically young girls, that enforce communication of society’s expectations of what girlhood should be.

– Olivia Sturgell

The “Saucy Walker” doll was manufactured by the company Ideal mainly between 1951 and 1957. They were manufactured in plastic and vinyl and were made in diverse sizes, the most popular of which was the 22-inch doll. The name of the doll, Saucy Walker, was derived from a combination of factors such as the walking mechanism and the doll’s ‘saucy’ personality. The saucy personality of the doll could be seen from the fact that the doll walked boldly. The dolls even rolls their eyes while turning their head to show how impertinently bold they were.

This ad shows that the doll can walk, turn her eyes, cry, and sleep. She even has washable hair. This ad communicates the limitations of girlhood in the 1950s; it depicts girls as focused on beauty (washing their hair), walking saucily, and caring for babies (being mothers to their dolls).

From a feminist perspective, in a patriarchal society, women are controlled and asked to behave like dolls under the invisible hands of men in power. The pressures of a patriarchal society can be seen from the lens of the doll ad. This is because the invisible hands of the men in society control women just like the girl in the ad control the doll. The doll narrative provides a male-dominated society that was clear in the 1950s and the 1960s.

– Nicholas O’Brien

This Sears catalogue from 1937 depicts a series of toy strollers, or “buggies,” catered to young girls. The image details various stroller designs, along with girls of the targeted age group using strollers for their dolls. The strollers are incredibly detailed and woven into the style of baby carriages that were used at the time to simulate a real stroller.

This reflects the popularity of baby dolls as toys for young girls, a pastime that remains popular among young girls to this day. Girls still play “pretend” by taking care of their doll as if it is their own living child, with fake cribs and strollers to furnish their fantasies. The girls in the catalogue are both dressed in clothing that appears formal rather than casual, implying that the demographic of consumers would be middle to upper-class families.

The companies that produced these toys seem to play into the idea that maternal nature is instinctual for the birth-assigned girl. Both girls are posed as “little mommies” in the photos beside their dolls, staring at them with adoration the way a mother would their child. One can assume that categorizing the baby doll (along with furniture like the doll stroller) as a girl’s toy contributed to the socialization and reproduction of a certain societal norm: girls being expected to become traditional household mothers and caretakers as opposed to pursuing a career path.

– Julia Kennedy

Advertisements like “Girls…win this Shirley Temple Doll!” from 1937 likely had a significant and long-lasting psychological impact on how girls viewed their self-image. At the time, gender roles were highly focused on appearance. Young girls were expected to conform to traditional norms of beauty and femininity. In this advertisement, the Shirley Temple doll was positioned as a prize for girls that reinforces these expectations.

This ad, which made the Shirley Temple doll a prize or bonus for subscribing to a magazine, asked young girls to center their self-worth on having this doll or looking like it. As the era’s epitome of cuteness, Shirley Temple reminded society of the expectations of girlhood. In addition, the advertisement reinforced the notion that girls should aspire to own dolls and other traditionally feminine toys. These notions have reinforced gender stereotypes and encouraged girls to focus on beauty pursuits and feminine roles of caring for others.

A further consequence of the advertisement is the blatant and obvious notion that white, middle-class femininity is the norm. The image of Shirley Temple, a white child actress who embodied the ideal of the “perfect” child star, was plastered across many products. It alienated girls from other racial or socioeconomic backgrounds and perpetuated the idea of white, middle-class femininity to which girls should strive.

The advertisement “Girls…win this Shirley Temple Doll!” from 1937 likely significantly impacted how girls felt about themselves during that period. It reaffirmed gender stereotypes, promoted the Shirley Temple doll as a desirable and appropriate prize for girls, and caused alienation among girls from other racial or socioeconomic backgrounds. No matter its historical context, this advertisement continues to shape our perceptions of gender and identity.

– Savannah Young

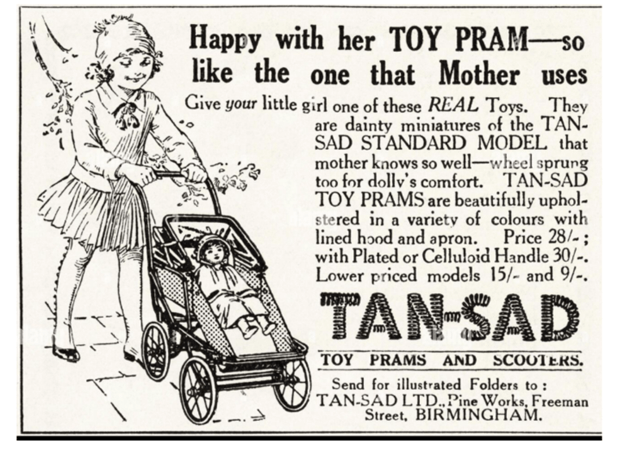

This ad for the “Tan-Sad Toy Pram” printed in 1923 is a stark example of how motherhood and domesticity were pushed onto young girls in the early nineteenth century through the activities and toys they engaged with. Looking at the ad, the eye is drawn to a little girl with perfect curls, clean looking clothes, and a gentle smile on her face happily pushing her toy doll in its stroller. The picture says to the viewer that little girls are content to take care of their children and become the little mothers they are destined to be. The girls’ eyes and stature point downward towards her doll, communicating that her focus should always be on the baby’s wants and needs rather than her own. Between her put-together, pristine look and satisfied expression, the ad directly plays into and encourages fitting these gendered norms for little girls’ in society at the time.

Once the little girl is seen, the eye follows to the words that connect and reinforce the ideas brought forth by the picture. The slogan “so like her mother uses” perpetuates the concept that little girls’ are meant to learn the role of the doting mother who cleans, cooks, and takes care of the children at home, and follow in her footsteps. Although the 1920s saw a shift in the ideal woman from one who was totally domestic to one who could work and enjoy leisure activities, the ad still promoted traditional ideologies declaring “mother knows so well” the lessons their little girl needs in order to keep the house running. While the idea of womanhood evolved, it seems that ads like this one stuck around for years in an attempt to maintain gendered norms and keep women content with the opportunities they were given.

– Caitlin Pingree

This advertisement is for the American Character Doll Company’s most popular doll “Tiny Tears” which was first introduced in the 1950s. The doll’s most marketed feature was its ability to cry real tears, which a child could “hear and see.” The crying mechanism was two small holes near the eyes that produced the tears once it was fed with water from her bottle and her stomach was squeezed. The doll had other advertised features such as sleeping, drinking its bottle, wetting its diaper, blowing bubbles, and being able to be bathed.

The “Tiny Tears” doll was created and advertised with the normalized teachings of preparing little girls for motherhood in mind. The language of this 1950s advertisement makes it clear that this toy is a tool of socialization, training girls (referred to in the copy as “proud young mothers,”) to care (notably pacify, feed, bathe, and cloth) for others. Because the doll replicates characteristics of a real baby, the girl’s play with her doll is depicted as a great way for her to start her maternal practice. The language also directly speaks to the parents of the child, stating that “your little girl” will be fascinated by the toy. This emphasizes the enjoyment society expected girls and women to receive from the responsibilities of caring for others.

– Arianna Cardenas

The ad entitled “Topper Toys: The Toys Your Children are Dreaming About,” reveals expectations of femininity in the early 1960s. The image depicts two children, a boy and a girl, sleeping. The girl in the image is shown to dream of playing with dolls. There is a doll that takes part in a beauty pageant and a dance party. There is also a doll named Dawn that comes with three different attachments of hair that a young girl is expected to play with. The third doll is called “Smartypants,” which means the doll can talk and answers the questions of, “How many toes do you have?” and “Am I touching the left or right hand?” These questions aren’t great indicators of intelligence and emphasize that not much is expected from young girls. The Smartypants doll also had the ability to say, “I love you, Mommy.” This insinuates that a girl should look forward to motherhood because the doll is meant to be treated as a real baby. Young girls were expected to play with babies because it was a way of practicing or pretending to be a mother years before this would become their reality. Even as the feminist movement was growing, during the 1960s men valued homemakers and expected women to be natural homemakers and nurturing mothers. Some women listened to their husbands and fulfilled their roles at home to satisfy their family’s needs.

Meanwhile, the boy in the ad is pictured dreaming about playing with toy race cars that are replicas of the Indianapolis 500 winners. Additionally, there is a toy named “King Ding” that is described as the smartest and most powerful robot toy in the world. The toys the boy desires hold stronger and smarter traits than toys meant for girls. The ad from Topper Toys describes the expectations of girls at this time. Girls were given toys that trained them to believe their role in society was less meaningful than that of boys. At an early stage of their lives, girls were told that their traditional role in society was to stay feminine, and submissive to their male counterparts. Toys trained young girls to acknowledge their futures as wives, mothers, and homemakers who had to labor in the home and also be beautiful like pageant queens.

– Bella Rosales

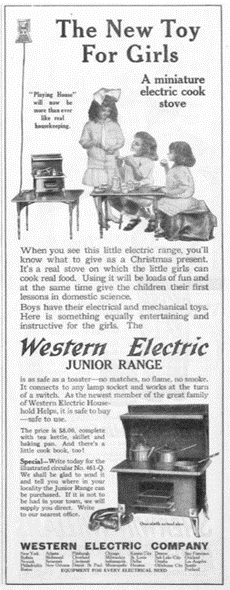

Western Electric was an electrical engineering and manufacturing company founded in 1869. During the holidays in 1915, the company promoted a new product: a miniature electric cook stove. During the 1910s, the idea of an electric toy for children sounds amazing and exciting. The advertisement for this electric stove toy, from the wording to the picture, was trying to reach a demographic of young girls.

At the top of the ad, the tagline “The New Toy For Girls” is in big letters. Under this announcement, in smaller font, the advertisement claims that this toy will make “playing house” more realistic. This is all framed as positive with the picture including a group of girls using the miniature stove. It appears that the girl standing up is the oldest of the three and she is the one serving the younger ones, like a mother would serve her children. The miniature electric stove and all its accessories sold for eight dollars. The girls playing with the expensive toy are all dressed up with their hair styled in curls with the oldest wearing a bow. Their appearances suggest the company wanted to reach young girls from upper-class families.

The ideas of what a woman’s role in life affected the toys for what a girl would receive. The advertisement states that while boys have their own mechanical toys, this was made for girls to start learning how to housekeep and for it to be portrayed as fun. This product enforces the idea to girls that once they grow into women, their role is at home in the kitchen.

– Yarethzy Aguilar

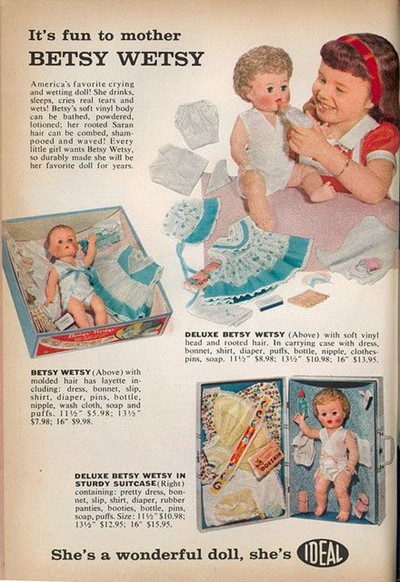

The Betsy Wetsy doll was first introduced in 1934 by the American Character Doll Company, and it was popular throughout the 1950s and 1960s. As a product of its time, the Betsy Wetsy ad portrayed women in a traditional role as caregivers and nurturers. Women of color had long worked out of the home, but gender roles and stereotypes about women as the primary caregivers was true for white woman and popular in mainstream media. Although many women were slowly realizing they could provide more than just being caretakers, around this time it was still common for men to be providers and the woman to be responsible for maintaining the house and taking care of the children. This advertisement communicates to young girls that they should prepare to be mothers and caregivers. The Deluxe Betsy Wetsy came with clothes and diapers and various items a ‘baby’ would need. This doll was meant to teach girls how real babies worked and teach them from an early age how to properly care for a child setting them up for adulthood.

The Betsy Wetsy doll was part of a larger cultural trend of idealizing and romanticizing motherhood and domesticity in the mid-twentieth century. This trend was particularly strong in the United States during the post-World War II era, when women were encouraged to leave the workforce and return to their traditional roles as wives and mothers. The Betsy Wetsy doll may have contributed to this cultural narrative by promoting the idea that a woman’s primary goal and source of fulfillment should be her role as a caregiver.

– Briana Pacheco

Suzy Cute was an extremely popular doll in the 1960s. The doll simulating a real baby would drink from her bottle, wet her diapers and even burp when her stomach was squeezed. In the commercial, an ensemble of young white girls and Louis Armstrong serenade the audience with all the ways Suzy is cute. Armstrong ends the commercial with the statement, “Girls, Suzy Cute needs a mommy. Suzy Cute needs you.” Calling out girls to take on the role of “mommy” is an attempt to directly turn young girls interests into a tunnel vision of motherhood and domesticated life. If that is actively one’s choice that is one thing, but to make it the ONLY choice is another. Taking away the consumers autonomy continues to feed into harmful misconceptions about gender and supports stigmas about what is deemed “normal” within a girl’s community and society.

This commercial came out in 1964, the same year as the Civil Rights Act as passed. This act would make discrimination based on gender and race illegal. This meant that women, regardless of race or age, would be able to take on more leadership roles and break out of the stereotypes of “the homemaker.” At the same time, it there was a lot of push back from people who were fond of tradition. This Suzy Cute commercial showcased that many people still wanted to track young girls into being domesticated and ensconced in the private sphere of the home. Using Louis Armstrong, a well-known Black jazz musician, within the commercial is an attempt to trick audiences into thinking that the doll and brand are progressive.

While the lightheartedness of the commercial may conceal the ideologies embedded in it, the intentions ring clear at the end with a call to action to young girls. Rather than pushing for girls to engage in intellectual or artistic pursuits, so many of the ads from this time period suggest that girls have a secret underlying urge to only be a mother and will be wholly fulfilled in that role. It lacks originality with the tired old tale of sexism guised as a progressive lighthearted commercial.

– Korie Large

Thank You

Special thanks to Dr. Emilie Zaslow, Professor and Department Chair, Communication and Media Studies at Pace University. Dr. Zaslow focuses on the connection between identity and mediated communication. She is interested in the ways in which we come to understand ourselves, and our worlds, through our relationships with media texts and technologies. Specifically, her research has explored how media impacts gendered identities and our perceptions of the feminine.

Also thanks to the students who participated in this course: Yarethzy Aguilar, Ari Cardenas, Natalie Estrella, Chloe Fuller, Stefanie Giacoumopoulos, Julia Kennedy, Korie Large, Makenzie Novak, Nicholas O’Brien, Caitlin Pingree, Bella Rosales, Eliza Rafter, Cali Snyder, Olivia Sturgell, and Savannah Young.

Finally, thank you to our team: Ashley E. Remer, Hillary Rose, and Tiffany Isselhardt for assisting with this course integration. We are truly excited about our first fully student-led show.

Want to Collaborate?

If you are an educator teaching high school or university courses, we are keen to work with you to create your own student-led exhibition. Please contact us to start the conversation.