In Black Studies’ burgeoning subfield known as Black Girlhood Studies, Black feminist scholars, notably LaKisha Simmons, Marcia Chatelain, Monique Morris, Nazera Sadiq Wright, and Lindsey Elizabeth Jones, have attended to the ways adults have historically subscribed to a moral panic and policed Black girls’ sexualities. Adults have weaponized their sexualities against them to punish them or ostracize them from community and continue to do so.

The ongoing conversation about Black girlhood, sex and sexuality has considered the patriarchal and anti-Black roots of the policing of African American girls’ sexualities during the antebellum period and in its afterlife. Some of these considerations center white people’s views of Black girls’ sexualities, while others focus on intracommunal dynamics.

Since my Black feminist politic is situated in the Black interior (Alexander x), or, the space in Black life that does not exist in resistance to or because of whiteness and white supremacy, I am most interested in the intracommunal dynamics. In particular, I am interested in how Black women police and survey the sexualities of Black girls, and how Black scholars have attended to this. African American girls, who have been considered metonyms for the future of the Black race and the perceived moral health of African Americans, have also long been perceived as future women, or Black-women-in-training. LaKisha Simmons and Marcia Chatelain both emphasize the consequences of Black girls who are caught being “wayward.” In cities like New Orleans and Chicago, just after World War II and during the Women’s Club Movement, sexually active Black girls, or Black girls who were perceived as girls who might become sexually active, were said to have brought shame upon their families and the race writ large. (Simmons 147) (Chatelain). One cited explanation of this was that if African American girls did not present as chaste, the image of “the race” might be soiled, ruining African Americans’ chances of being treated with decency by white people, who wielded economic and political control over many avenues of public life (Chatelain) (Simmons). One other reason for this policing, intracommunally, was the notion that Black girls appearing promiscuous made them more vulnerable to sexual violence at the hands of white men, for which parents and other adults could not always trustingly seek legal recourse during the early 20th century (Wright) (Crenshaw). One other reason was because, due to the social manifestations of patriarchy within intimate partnerships, some older and experienced Black women worried that a young girl who was interested in sex with boys could have her heart broken by a boy who was not responsible with her feelings or body (Collins).

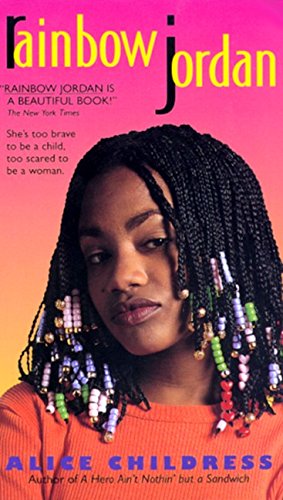

I am curious about what else lies beneath the seeming preoccupation with the sex lives of African American girls, particularly among African American women who care for and advocate for them. I use the phrase “sex lives” instead of merely the term “sexuality” because of the assumption that Black girls protecting the inner parts of their lives, or dissembling, as Darlene Clark Hine would call it (Clark Hine 912), means being secretive about an evolved and exciting sex life. I turn to one example within Black women’s literature in which Black women demonstrate curiosity about a Black girl’s sex life. While elsewhere I reflect upon a wide range of novels written by Black women and about Black girls from the 1970’s through today, here I recall and analyze a scene from Alice Childress’ 1981 novel, Rainbow Jordan, because it was one of the first novels that might have be categorized Black young adults’ literature.

14-year-old Rainbow is sent to Josephine, whom she calls Miss Josie, for her interim foster care since her mother leaves her alone for several days to weeks at a time. She was born when her parents were sixteen years old and, and they divorced not long after her birth. Kathie, her mother, has been arrested multiple times throughout Rainbow’s young life, namely due to child endangerment, and her father lives far away but sends money as often as he can. Miss Josie is both enamored with and annoyed by Rainbow, a despondent child who adores the mother who often leaves her behind. Miss Josie hates the way Rainbow plays with her food until it’s all mashed together—eating that way in public reflects poorly upon “the race.” Miss Josie is there when Rainbow has her first menstrual cycle, and explains that this means she can now become pregnant. Rainbow asks if “bad girls” get pregnant, and Miss Josie explains that notions of “good” and “bad” girls are more complicated than that. Later, when Rainbow arranges to have sex with a boy for the first time by sneaking from Miss Josie’s house to her mother’s unchaperoned apartment, the boy brings his new girlfriend to the apartment—it’s a move to show Rainbow that he no longer needs her, as she has waited too long to give in to his requests to have sex. Miss Josie senses Rainbow is in the apartment, and barges in just after the boy and his new girlfriend have left, and as Rainbow sits there, heartbroken.

“’He tried to take advantage. Did he?”

“No, mam. I asked him here. He brought his new girlfriend with him. I put on my mother’s caftan…I waited for him to come and go to bed with me. He brought his new girlfriend.”

“I’m glad.”

“Sorry you glad. It broke my heart’

“Child, you’re better off than you know’

‘You know that, I don’t’” (124).

We have access to Miss Josie’s thoughts in other chapters because the novel alternates between Rainbow’s first person narrative, Miss Josie’s and Rainbow’s mother’s, so we know that Miss Josie cares a great deal about Rainbow, and would never be glad to see her heartbroken. She is glad, though, that Rainbow did not have sex with the boy. She is so relieved that she expresses her relief instead of comforting Rainbow. Whether this is dramatic irony is dependent upon the reader is, how they experienced girlhood (if they experienced girlhood), how they experience sex, and how they read girlhood and sex. Some readers might understand Miss Josie’s perspective even if she does not explain it. Some readers might be frustrated with Miss Josie’s seemingly callous stance. In any event, Miss Josie indexes a decades-long tension that rests somewhere between policing a Black girl’s sex life, and protecting a Black girl from heartache. Popular among Black girl readers during the 1980s, Rainbow Jordan includes scenes that are equal parts heavy-handedly didactic and descriptive for readers, much like the conversations between some Black women and Black girls about the joys and torments of having an active sex life in a patriarchal and anti-Black world.

This scene is just one in a literary tradition in which Black women writers illustrate or assess the age-old curiosity about Black girls’ sex lives, or what some adults have perceived as sex lives. Audre Lorde makes a similar move in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name: A Biomythography, as does June Jordan in His Own Where, and Jamaica Kincaid in the short story, “Girl.” This paternalistic age-old question, “is she having sex?” might easily be countered with “why does it matter?” by adult and girl feminists alike, and putting Black women’s writing in the context of anti-Black racism and patriarchy as well as an ethic of care and compassion for Black girls helps elucidate this question’s relevance.

-Destiny Crockett

Guest Contributor

Originally from St. Louis, Missouri, Destiny Crockett (she/her) is a 3rd year doctoral student in the Department of English at the University of Pennsylvania. She studies Black feminist theory, 20th and 21st century African American women’s literature, cultural productions, and literary archives, as well as Black girlhood studies. Destiny earned her B.A. in English, with certificates in African American Studies and Gender and Sexuality Studies, from Princeton University in 2017.

Works Cited

- Alexander, Elizabeth The Black Interior: Essays. 2004, Graywolf Press, Minneapolis; MN.

- Chatelain, Marcia South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration, 2015, Duke

- Childress, Alice Rainbow Jordan, Coward, McCann, & Geoghegan, Inc, New York; NY. 1981

- Clark Hine, Darlene “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West.” 1989, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society.

- “The most unprotected of all human beings”: Black Girls, State Violence, and the Limits of Protection in Jim Crow Virginia, Lindsey Elizabeth Jones, 2018, Souls

- Simmons, LaKisha Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans, 2015 UNC Press

- Spillers, Hortense “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words” (2000) Black, White, and In Color, 2003, University of Chicago Press

- Wright, Nazera Sadiq Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth Century, 2016, University of Illinois Press