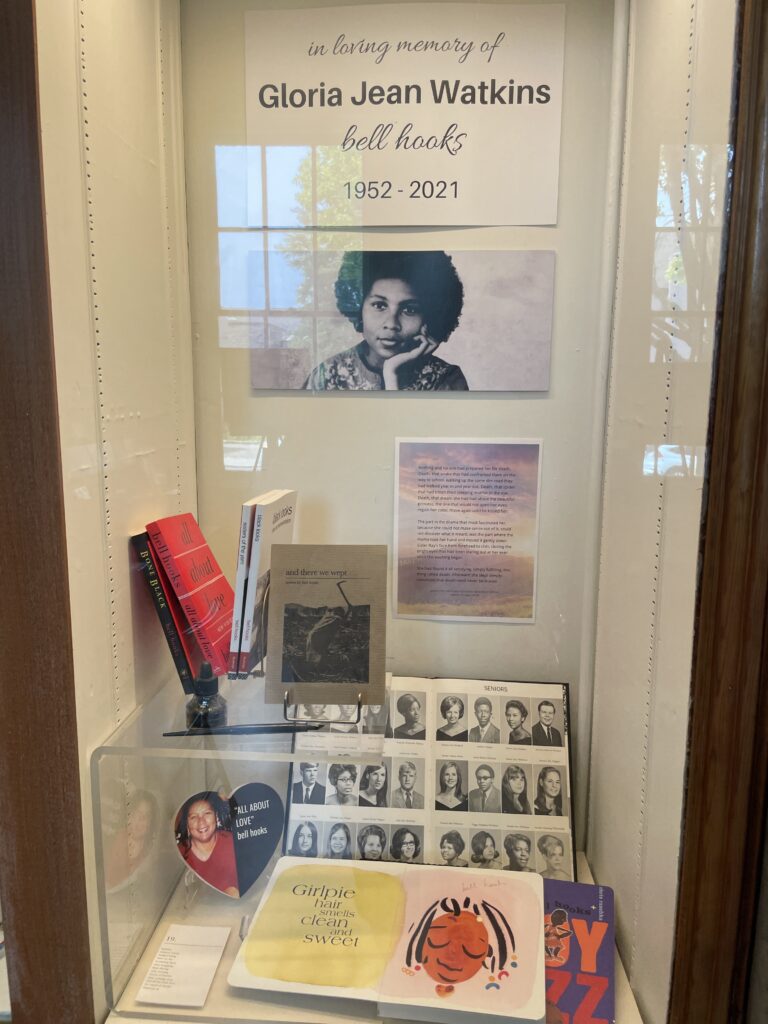

At a small museum in a small Kentucky town, I found bell hooks’ girlhood. Visiting during a recent museums conference, I was exploring the many displays at the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County: home to many intriguing historical figures. And among the many displays sat a case of books, photographs, papers, and a Yale University ID card…all belonging to bell hooks.

Born Gloria Jean Watkins in 1952, the girl who would become notable African American author and activist bell hooks was from Christian County, Kentucky. Gloria attended racially-segregated public schools and performed poetry readings at her church. As The New Yorker would later summarize, it was these segregated experiences that impacted Gloria most:

She loved movies, yet the ways in which the theatre made us occasionally captive to small-mindedness and stereotype compelled her to wonder if there were ways to look (and talk) back at the screen’s moving images. Growing up, her father was a janitor and her mother worked as a maid for white families; their work, rife with minor indignities, brought into focus the everyday power of an impolite glare, or rolling your eyes. A new world is born out of such small gestures of resistance—of affirming your rightful space.

“The Revolutionary Writing of bell hooks”

She was also heavily influenced by her maternal great-grandmother, from whom she chose her pen name, and the stereotype of Kentucky as an entirely white state (which it was – and is – not).

hooks writes about Kentucky in belonging: a culture of place and challenges notions of its inherent whiteness in Appalachian Elegy: Poetry and Place. As the keynote for Berea’s Appalachian Writers Symposium in 2015, hooks asserted, “I always take the motto, like the queer motto, ‘We’re here.’ I feel that about myself as a Black person in the hills of Kentucky. I am here, and there’s nothing but love within me for the world around me.”

Berea College

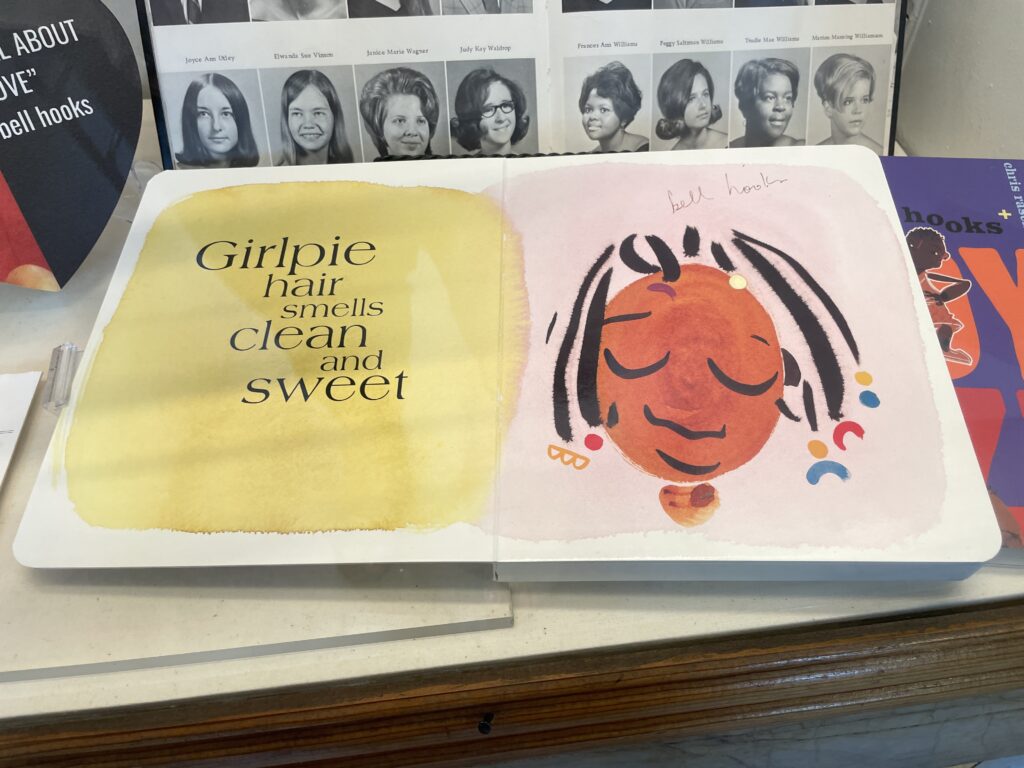

Awarded a scholarship to Stanford, Gloria – becoming bell – left Kentucky in the late 1960s, eventually earning her doctorate. bell hooks published her first volume of poetry in 1978, at the age of 26.. Her poetry in And There We Wept and her 1981 seminal work, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism explored the intersection of race, sex, and class at the core of black women’s lives. She was one of the foremost thinkers about intersectional oppression – something girlhood and Black feminist scholars know well. bell’s work led to her joint appointment teaching English and African American studies at Yale in 1985. She would continue teaching and publishing, later at Oberlin College then the City College of New York.

In 2004, bell hooks finally returned to Kentucky, accepting a position at Berea College as Distinguished Professor in Residence in Appalachian Studies.

“I felt very much that I wanted to give back to the world I came from,” she says. “I grew up in the hills of Kentucky, and I wanted these students to see you can be a cosmopolitan person of the world but still be connected positively to your home roots.”

bell hooks, on why she returned to Kentucky (Berea College)

In 2013, Berea created the bell hooks Institute to preserve her legacy, then opened the bell hooks Center in September 2021 – just three months before bell died at the age of 69. And while bell’s legacy lives on in the students whom she taught, those who have read her works, and the many who she inspired, there is a series of displays at a small museum in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, that remind us that – once upon a time, in the early 1950s and 1960s – bell hooks was once a young girl named Gloria who dreamed of a better world.

-Tiffany Isselhardt

Program Developer

(All photos courtesy Isselhardt / displays from Museums of Historic Hopkinsville, 2023)