The emancipation of slavery did not happen overnight. As with any social movement, slavery’s end came about through a long process of people advocating against the institution. This included the words and actions of girls! As we honor Juneteenth, we also honor the contributions of Black girls who helped propel anti-slavery and abolitionist sentiment towards emancipation.

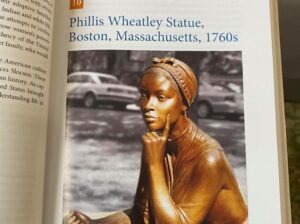

Phillis Wheatley

Named for the ship which bore her into slavery, Phillis was kidnapped in Senegal or Sierra Leone and sold into slavery at Boston Harbor in 1761. Purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, Phillis became a domestic servant and companion for Susanna. Her capacity for learning was soon recognized, and Phillis was tutored alongside the Wheatley children in English, Latin, history, geography, and the Bible. By age thirteen, Phillis was publishing poetry – though the Wheatley’s kept the profits – and corresponding with Black writers in Boston and Newport. In 1770, one of her poems sparked national renown. By 1773, her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published throughout the Atlantic world.

Within the book were poems that subtly hinted at politics. Notably, recent analysis has indicated that the language utilized in her poems sought to criticize slavery through the use of double meanings and metaphors. Of her forty-six known poems, eighteen are elegies that contain themes of black freedom as akin to death or a voyage over water – metaphors found in slave spirituals. Her life is one of the first long accounts of black girlhood in Colonial and Revolutionary America.

While Phillis’s writings did eventually result in her freedom, Phillis never saw the profits of her writings. The Wheatley’s kept all proceeds from her earlier works, and any post-emancipation works have been lost to time.

For a full biography, click here.

Harriet Jacobs

Born around 1813 or 1815, Harriet’s autobiography – Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl – was published in 1861 and quickly became a rallying cry for the Union during the American Civil War. It remains an American classic today, still utilized in history classrooms.

Harriet was born enslaved in Edenton, North Carolina, and owned by the Horniblow family. At the age of six, her owner taught her to read, write, and sew. At age twelve, Harriet’s owner died, and she was willed to Dr. James Norcom and his family. Dr. Norcom sexually harassed Harriet, causing Norcom’s wife to become jealous and engage in further harassing behavior. In 1835, at about the age of twenty, Harriet decided to escape slavery. She hid first in a nearby swamp and then in a 9-by-7-foot crawlspace in her grandmother’s house (only 600 feet from Norcom’s house). Harriet remained in this space for seven years, until 1842 when she escaped to Philadelphia by boat, then continued on to New York City. Nearly a decade later, Harriet became involved in the circles that led to her writing Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

Published in 1861, and as related by the Advancement Project, “Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents transformed the conversation around slavery at the time, providing a powerful testimony to the pervasive role of sexual violence, garnering support for the abolitionist movement like never before.”

You can read the entirety of Jacobs’s Incidents online here, courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Born free in 1825, Frances was raised by an aunt and uncle after her parents died. She attended the Academy for Negro Youth in Baltimore until age 13, then worked as a domestic laborer and teacher. At age twenty, she published her first collection of poetry – Autumn Leaves – and continued to publish poems and novels throughout her life. She also became a traveling speaker on the abolitionist circuit, a conductor for the Underground Railroad, and a writer for anti-slavery newspapers. Her writings often focused on slavery and, later, Reconstruction, women’s rights, and educational opportunities for all.

Eliza Harris

Like a fawn from the arrow, startled and wild,

A woman swept by us, bearing a child;

In her eye was the night of a settled despair,

And her brow was o’ershaded with anguish and care.She was nearing the river—in reaching the brink,

She heeded no danger, she paused not to think!

For she is a mother—her child is a slave—

And she’ll give him his freedom, or find him a grave!’Twas a vision to haunt us, that innocent face—

So pale in its aspect, so fair in its grace;

As the tramp of the horse and the bay of the hound,

With the fetters that gall, were trailing the ground!She was nerved by despair, and strengthen’d by woe,

As she leap’d o’er the chasms that yawn’d from below;

Death howl’d in the tempest, and rav’d in the blast,

But she heard not the sound till the danger was past.Oh! how shall I speak of my proud country’s shame?

Of the stains on her glory, how give them their name?

How say that her banner in mockery waves—

Her “star-spangled banner”—o’er millions of slaves?How say that the lawless may torture and chase

A woman whose crime is the hue of her face?

How the depths of forest may echo around

With the shrieks of despair, and the bay of the hound?With her step on the ice, and her arm on her child,

The danger was fearful, the pathway was wild;

But, aided by Heaven, she gained a free shore,

Where the friends of humanity open’d their door.So fragile and lovely, so fearfully pale,

Like a lily that bends to the breath of the gale,

Save the heave of her breast, and the sway of her hair,

You’d have thought her a statue of fear and despair.In agony close to her bosom she press’d

The life of her heart, the child of her breast:—

Oh! love from its tenderness gathering might,

Had strengthen’d her soul for the dangers of flight.But she’s free!—yes, free from the land where the slave

From the hand of oppression must rest in the grave;

Where bondage and torture, where scourges and chains

Have plac’d on our banner indelible stains.The bloodhounds have miss’d the scent of her way;

The hunter is rifled and foil’d of his prey;

Fierce jargon and cursing, with clanking of chains,

Make sounds of strange discord on Liberty’s plains.With the rapture of love and fullness of bliss,

African-American Poetry of the Nineteenth Century: An Anthology (University of Illinois Press, 1992)

She plac’d on his brow a mother’s fond kiss:—

Oh! poverty, danger and death she can brave,

For the child of her love is no longer a slave!

Louisa Picquet

Born around 1829 in South Carolina, Louisa was 1/8th African and considered a “white passing” enslaved person. Sold as a young child, Louisa was moved to Mobile, Alabama, where she performed domestic duties for a time before being sold at auction to another slave owner in New Orleans – separating her from her mother and brother. In the 1840s, Louisa obtained her freedom and moved in with a friend, working to raise money so she would move with her children to Ohio. After moving to Ohio, Louisa focused on finding and freeing her mother and brother. Though she never found her brother, Louisa successfully found her mother and able to negotiate the purchase of her freedom in 1860.

During this time, Louisa traveled the country to secure money for the purchase. While in Buffalo, New York, she met with abolitionist pastor and author Hiram Mattison, who published her slave narrative – Louisa Picquet, the Octoroon, or, Inside Views of Southern Domestic Life – in 1861. The narrative is structured as an interview and includes the letters between Louisa and her mother as well as newspaper clippings.

Louisa’s narrative is unique in exploring her 1/8th African ancestry, which resulted in a very light complexion. Like many with light complexions, Louisa was often questioned on her Blackness and others struggled to perceive her as a former slave. Louisa wrote about being a white passing enslaved person, drawing attention to the irony of racialized slavery.