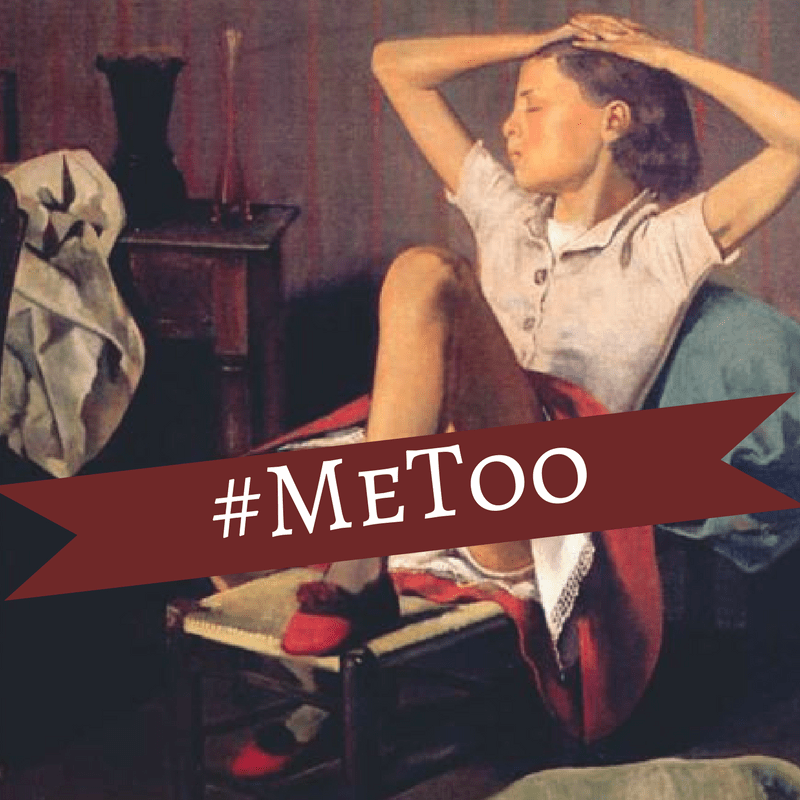

Original‚ Thérèse Dreaming, Balthus, 1938, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Just look at the painting.

You do not need any special pedigree, beyond being sighted. In fact, a blind person could tell you, if the painting were being described to them, that something is not right.

This painting is called Thérèse Dreaming, by Balthus, and was made in 1938. Most girls Thérèse’s age (12 or 13) wouldn’t sit like that without being asked or compelled. Imagine how it felt to sit with your legs spread and your dress hiked up facing an older man‚ your next-door neighbor. No wonder she is looking away. Balthus gives the viewer permission to consume her image without challenge.

Did Thérèse see this painting? What did she think about it?

We don’t know. No one asked. No one cared to ask. It is almost heretical to think to ask a girl her opinions or thoughts. What if her narrative included a sexual assault? We don’t want to know. Especially because we can’t say sorry and that it will never happen again. Because it likely will.

In late November 2017, Mia Merrill, a local New Yorker, started a petition asking the Metropolitan Museum of Art to either remove this painting from view or amend the wall text to acknowledge the potentially disturbing nature of it.

“At the end of the day, we are talking about an artist who asked very young girls to come to his studio and take their clothes off,” Merrill told The New York Times in an interview. “What does that do to the question of consent?”

Her petition had over 11,000 signatures, yet much predictable backlash as well. The result is not surprising. The Met will do nothing, beyond enjoy the attention the painting will now receive. But petitions start conversations–why else would the White House have taken down the public petition site ‘We The People’ if it wasn’t important, or even dangerous, to their agenda?

It was another White House action in 2009 that encouraged me to start Girl Museum. President Obama announced the White House Council on Girls and Women the same week I founded the first and only museum in the world dedicated to celebrating girlhood. There was a need: a need to respond to the exploitation of girls in art, society, culture. A need to let their voices finally be heard. A need to interrogate how we have represented, consumed, and ignored girls throughout history.

History, academia, and media discourse generally do not consider girls as subjects. Girls are the perpetual objects–their subjectivity is not of interest, unless it is to get them to buy something. Humans learn visually; we mimic what we see. And we learn to devalue girls in both image and reality.

This is best seen in how museums talk about girls in art. They highlight only the artists’ story, possibly with a few anecdotes about who the girl in the painting is or why she is there. In most exhibitions we have seen in other museums, girls’ voices and stories are missing. We learn only about the ‘great artist’ and his vision, not the girl and her place in the world.

Original‚ The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer, modeled ca. 1880, cast 1922, Edgar Degas, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When I worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a Security Officer in the early 2000s, I encountered visitors, typically men, lifting the cloth skirts of Degas’ The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer. After admonishing them for touching the art, I would ask, “What did you expect to see under her skirt? Would you try that with a real girl?” Most were embarrassed at being caught, so they shuffled silently away. But a few did give what can now be described as a Trumpian reply.

We have a hard time relating to a girl in a painting, despite the fact that she was a real person. Unlike many models, we know her name is Thérèse. And that she is dreaming. Or perhaps the artist is dreaming about her. The title can be read many ways.

And what was the relationship this man had with his neighbors’ children? Many artists, Lewis Carroll (photographer and the author of Alice in Wonderland) for example, had suspect relationships with young girls, but we appreciate their art, so we let it go. Models were not protected, not then and not now. Was Thérèse protected? Was she a model and nothing more? Who ultimately is sexualizing her–the artist, or the viewer?

There is an argument that we–the viewers–are the ones sexualizing these paintings. If Thérèse did voluntarily sit as she does, perhaps she was bored, tired of being told what to do, or trying to exert some control in her situation. In this case, we must turn to two things. First, what we know of Balthus’ relationship with Thérèse: that she had been his model for a few years by the time of this painting, and that Balthus had painted her many times.

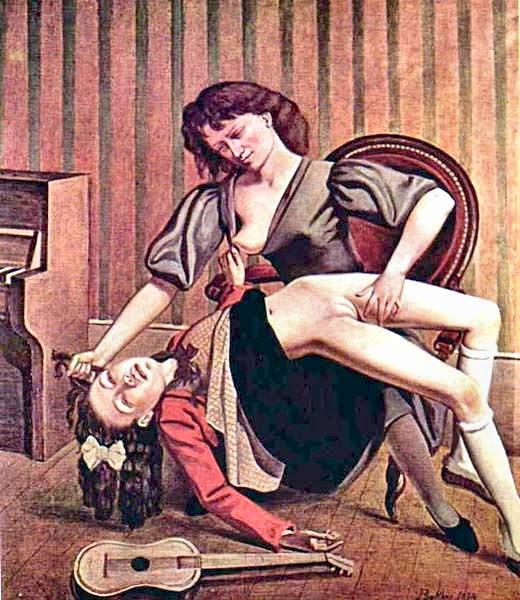

Guitar Lesson, Balthus, 1934, Private Collection.

Second, we must look at Balthus’ other work in order to put Thérèse Dreaming into context. Fours years prior to Thérèse Dreaming, Balthus painted Guitar Lesson. Does this make his intentions or internal machinations any clearer? Or does it lead to more questions about the artist and, more importantly, his subjects? He went on to paint many other similarly posed girls of the same age. Some more provocative, yet more clothed. In his last years, he took over 2000 polaroids of a girl (from the time she was 8 until she was 16 years old) in varying states of undress. These were studies for his last painting, of her completely nude.

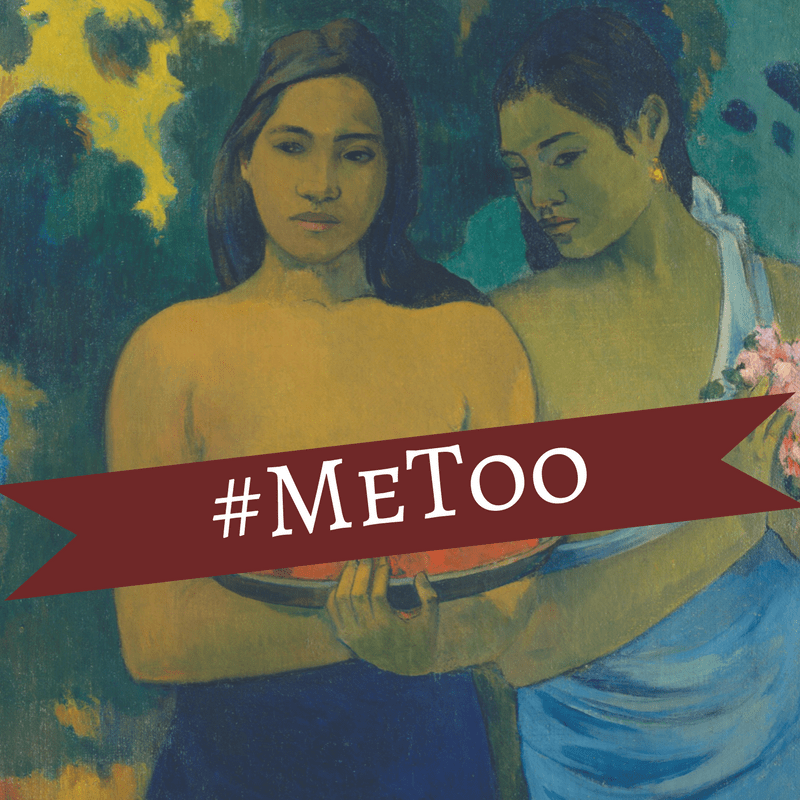

Original‚ Two Tahitian Women, 1899, Paul Gauguin, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For a short art history lesson, let’s meet Paul Gauguin. He was a French artist of the late 19th century, usually discussed in terms of his use of color. He also travelled to Tahiti, possibly bringing syphilis with him, and ‘married’ a 13 year old girl. Her story is not considered important, despite the fact that he used her and other underage Tahitian girls to make some of his most famous works. His artist-adventurer life has inspired generations of artists and potential pedophiles to tour the Pacific and other destinations seen as ‘exotic’ and easily exploited.

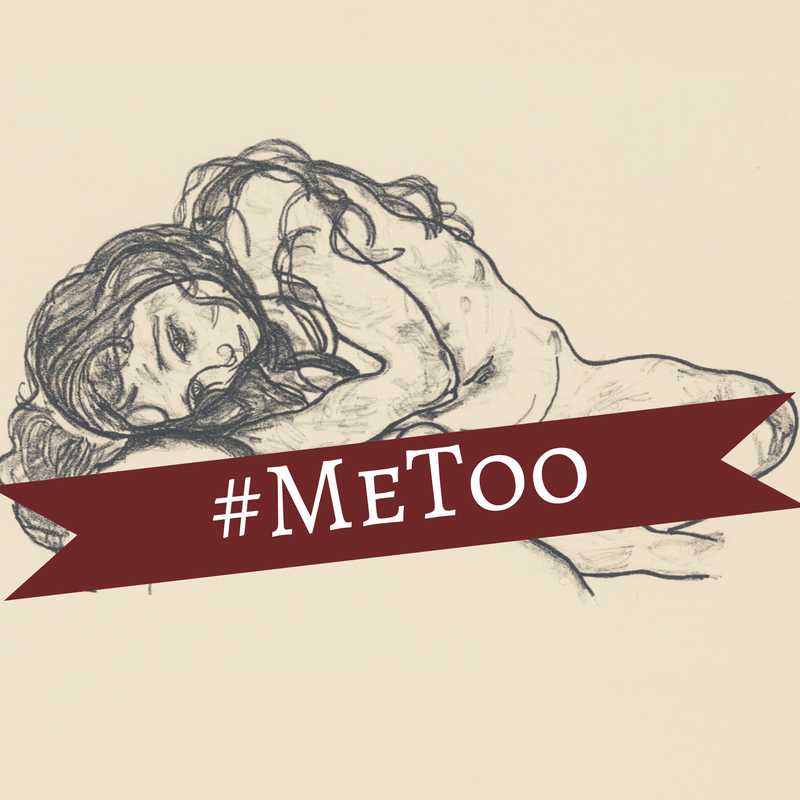

Original‚ Girl, Egon Schiele, 1918, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As subjects, children are used, yet disregarded, and girls doubly so. Even as parents, we don’t generally ask our children to take their picture; we relish the candid shot. We make children into subjects, decide on the point of view to present, and imagine that anyone seeing the image will see exactly what we see. But do they actually see what we see? Does an artist care about a child’s consent? Do you think their artworks can tell us exactly what they were thinking, feeling, seeing? Egon Schiele was well known for his use of young, vulnerable girls in explicit imagery. He is given an ‘artist pass’ to do so. And we, his viewers, take the pass to view his work without questioning what we are actually looking at and why.

(White male) artists do not generally get held accountable for what they do for their art. We put them on pedestals and bask in the halo effect of the righteousness of their creations. They get put in museums, galleries, academies, and halls of fame. This protects and enshrines them. Whosoever dares question the dignity and integrity of those inside–be damned. As art historians, to question the value of a work or an artist’s intention is taboo, especially at an institution such as the Met. A museum’s job has long been making the art as important and valuable as possible for its trustees, endowment, and visitors. Not to question, but to present and praise.

Since museums are educational institutions, we beg to ask, “Why can’t you do both? Why must we place one story (the artist’s) above another (the girl’s)? Why can’t we question everything, in the hope of finally finding the truth?”

Art has always reflected societal values and norms, which we like to think have progressed, but not really. People have always done cruel, bad, wrong things, no more in the past as today. Art also influences on our society as almost a way to excuse behavior that would otherwise be criticized and even criminalized. This is most recently evidenced by the film, I Love You, Daddy, by serial sexual harasser Louis C.K. We can also see it in the Weinstein/Allen/Polanski situations as well. (Arguably) Good art made by bad people. We have excused things some artists do because we believe in the supremacy of aesthetics, not of morality. They become ‘problematic favorites,’ not ‘rapists who create.’

Yet no artwork or artist is entirely innocent. We have to accept that notion, learn from it, and understand how it affects who we are and how we process images as a culture. Otherwise we just make the same mistakes over and over and over. We fail the girls whose voices have fallen silent, whose stories remain untold, and whose images are seen in every museum in the world. Museums like the Met want their art to maintain its value, its prestige, its social currency. It isn’t good for them when a series of paintings by a famous male artist is discovered to be an archive of sexual exploitation and assault.

Men in power being sexual predators is not new–being called out in public is. Men are men, regardless of whether they are in the White House or the corner store; there is always a risk for girls and young women to be exploited, albeit on a spectrum. A new secret, like artist Chuck Close being sexually aggressive to his sitters, or an open one, like photographer Terry Richardson abusing his models for decades, all are finding their way into the light. And this is a good thing.

At Girl Museum, we advocate for girls, who bear a disproportionate burden of social injustice. Art is a record of human achievements and failures. It is also a doorway into our souls, both past and present. It is a way to discuss and seek truth. And it is a place where we can finally give girls the representation, the history, the positive attention, that they have long deserved.

We do not ask for censorship.

We ask for responsible exhibiting. For full representation and inquiry into more than just the artist and their work, but into all the ways the work can be viewed and interpreted.

Information and contextualization are not hard things to ask of curators. It is their job, especially in public serving, non-profit institutions. Curators are educators and should be accountable for their decisions. So should artists. And so should we.

-Ashley E Remer

Head Girl

Girl Museum Inc.

————–

Note: All artworks, except ‚ Guitar Lesson, are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s permanent collection. It is a collection of hundreds of thousands of objects, with a small fraction of those being on display. So there are CLEARLY choices being made about what is worthy of showing and what is not.

Wonderful piece! Timely and provocative. This is the start of a new conversation….I hope!

Wonderful, Ashley!

What museums everywhere need is interpretive signage that can shift viewers angle of vision. Seeing art through a girl-focused intersectional lens can kindle critical thinking, provide historical perspective, foster empathy, and promote political action.

Two wonderful studies I recommend are: (1) ANGELS & TOMBOYS: GIRLHOOD IN 19TH-CENTURY AMERICAN ART by Holly Pyne conner (Newark Museum, 2012) and YOUNG AMERICA by Claire Perry.

Hi Miriam! Thanks so much for the recommendation – we will definitely check them out. 🙂

Ashley – it is very obvious that you put much time & thought into this piece. You have even included some very “quotable” lines (that I am thinking about putting into calligraphy). As others have already noted, what you have said deserves to be included in the conversation about women–and girls–and how we can end the exploitation and harassment. Thank you for advocating for a population that needs to have a voice.