Who were the millions of women and girls whose lives were impacted by WWI?

This exhibition continues our Heroines Quilt project, highlighting girls and women who made contributions to WWI. Theirs are stories of individuals and groups of girls on all sides of the home front and beyond—from family to fashion to music to work. These girls faced hardship and loss on a previously unimaginable scale. Many grew up to fight in the Second World War, greatly influenced by their childhood experiences.

Young children feed chickens on a British farm during the World War One. Image via BBC.

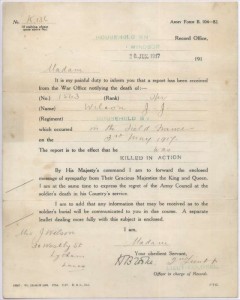

The First World War brought about great changes within girls’ home lives. Many faced the absence of father, uncles and older brothers. This absence was unbearable, but for those who lost all contact with their loved ones, like Gert Adams, permanent separation was made a reality. After six months of chasing news of her husband, Gert was notified of his death.

Other changes happened when girls left home to join the war effort. Although less common in Western Europe and America, many girls did join the men on the front lines. This was especially true in Southeastern Europe, where women had recently fought in the Balkan Wars. One such woman was Sofia Jovanović of Serbia, who was tasked to lead a battalion of men to capture an Austrian stronghold and cut communication lines.

By the end of the war, 9 to 15 million people had died. And the casualties weren’t limited to men. By 1916, Serbia alone had lost 40,000 women due to ill health and malnutrition. Elsewhere, like in India, girls who survived the war were placed into difficult situations when their fathers died, leaving their mothers penniless and their property – maybe even their lives – now controlled by their father’s family.

Female munitions workers guide 6-inch howitzer shells being lowered to the floor at the Chilwell ammunition factory in Nottinghamshire, UK, July 1917, WikiCommons.

Other absences were created by war work. Many young women left home for the first time to work in specialist compounds. The Canary girls of the munitions factory were situated on private compounds where they lived and worked with some significant side effects, like their skin turning yellow due to sulphur exposure, with deaths frequently happening around the factories.

Man holding a heavy loaded bicycle in balance, two children and a large bundle of clothing on it, a woman and and other man helping. The children warmly dressed. Refugees from Antwerp. Belgium, 1914, Nationaal Archief.

The standard of living for families was largely affected by their location. The majority of the fighting took place on the European continent, in places like France, Belgium, and Germany. Those living on the front lines faced food shortages and violence every day.

In Germany, school children suffered malnutrition, anaemia, and tuberculosis. In France, an area the size of Wales was destroyed through trench warfare and 40,000 civilians died. Many families had to move out of their homes, and in some cases, entire towns were destroyed.

On the other hand, people who lived away from the fighting, like in England, had a much higher standard of living. British school children’s cleanliness, nutrition, and health increased despite the war. Children living outside of conflict zones were encouraged to forego sugar and collect excess wheat to be sent to the soldiers and refugees.

But this wasn’t the case in all countries. In India, high taxation to fund war efforts left many girls and their families struggling. The disruption of trade caused prices to rise, and many were left deeply in debt just to survive.

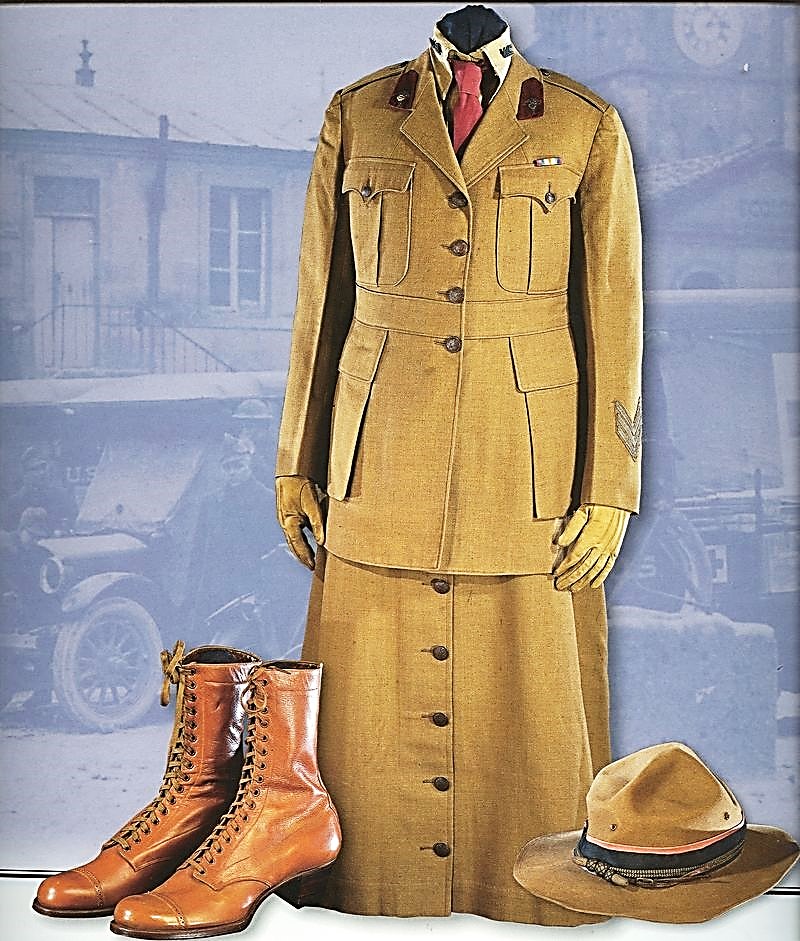

The Women’s Royal Air Force during the First World War. Members of the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) on board an RAF lorry circa 1918, WikiCommons.

War also had its own effect on family life. Rising numbers of fathers signed up and shipped out to the trenches in Belgium, France and Germany.

Governments involved in the war used all the methods at their disposal to drum up national support for the war effort.

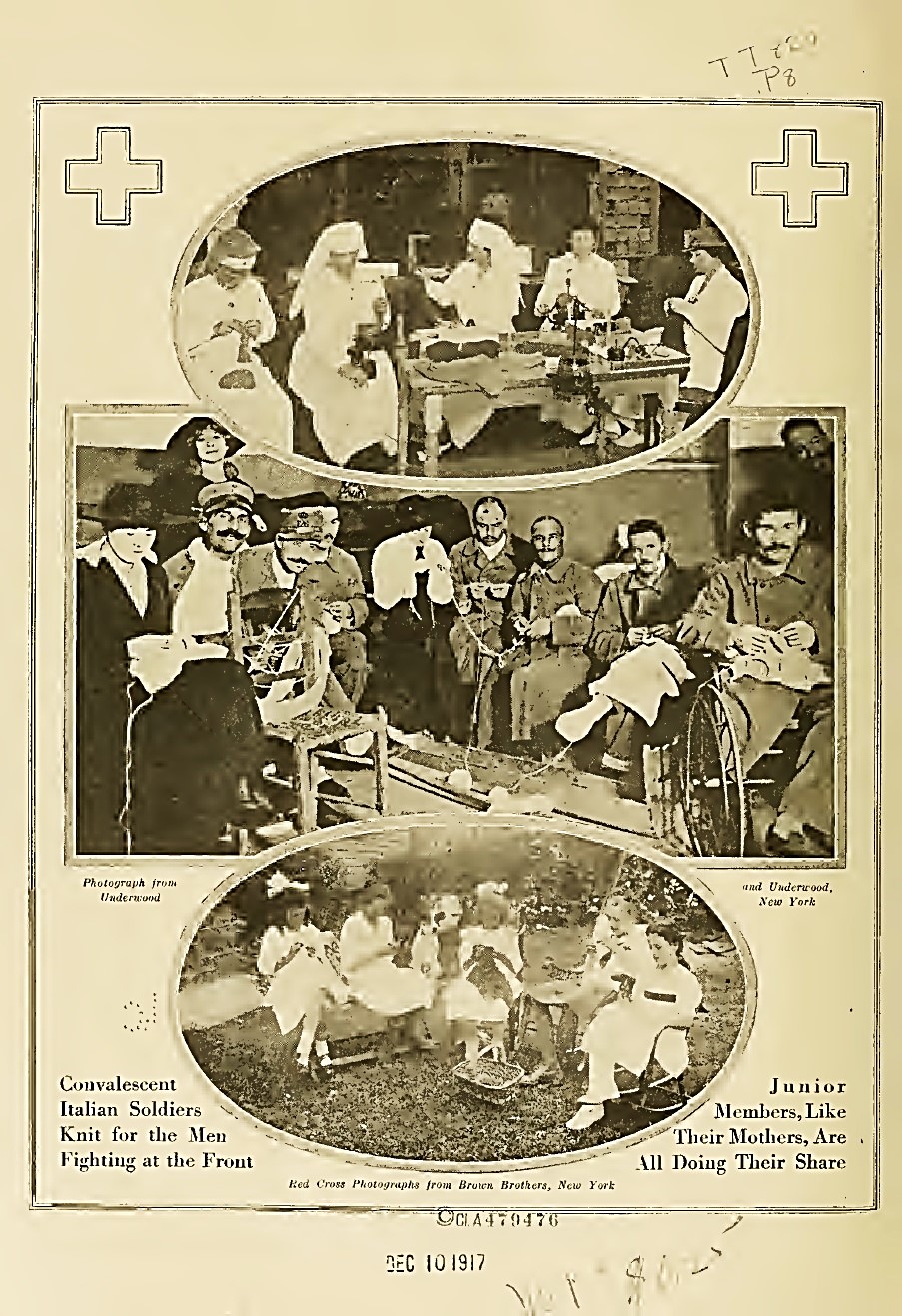

In Canada, many young girls helped to make bandages, collect books and newspaper, and baked goods for the soldiers.

In Australia, women volunteered with organizations like the Australian Red Cross and Australian Women’s National League. And in New Zealand, the Women’s Royal Air Force was created. Despite the distance, the home front still supported their soldiers with as much ferocity as if it were on their own front step.

The sense of loss and deprivation due to rationing, death and financial hardship were similar for children around the world.

Older siblings, mainly older sisters, were tasked with looking after younger siblings if their mother had to go out to work. Many would continue to do so, or have to find work themselves, when fathers or brothers died in the war. This forced many to quit school early and to take on adult responsibilities while still children themselves.

By the end of the war, the world was faced with a generation of under-educated children.

Dickinson children, dressed up in WW1 army, navy and nursing costumes, 10 Feb 1916, WikiCommons.

The children of Auckland and Wellington in New Zealand challenged each other to build a trail of copper coins, following the main truck line between the two cities and meeting each other in the middle, which provided lots of money for troops.

Girls also contributed to the war effort by knitting and sewing socks and scarves to keep troops warm. They sent letters to soldiers along with clothes, food and other small items.

Yet the war also impacted other ways of having fun, which served as constant reminders that the world was at war.

Patriotic toys, via BBC.

While pre-war children dreamed of owning a German-made Steiff bear, the war made this impossible. British toy companies rushed to create patriotic British bears to satisfy the demand. Some of their favourite, but foreign-made, toys disappeared from shelves, replaced by items made locally. These were not always as successful as the toys they replaced, but both patriotism and the disruption of trade necessitated national toy production.

As the war progressed, many of the factories that produced toys in Britain were claimed by the Ministry of Defence and started to make uniforms, bombs, and bullets. The availability of new toys during the war decreased and children increasingly relied upon their imaginations and what they had already at home.

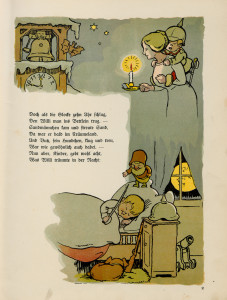

Hurray! A war picture-book, 1915, Herbert Rikli, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

A book entitled Hurray! A War Picture-Book was published and widely read in Germany, explaining the war and encouraging its young readers to actively support the war effort.

On the other side of the world, the New Zealand School Journal, first published in May 1907, offered readers feature sections on Gallipoli and the Western Front, in addition to reports on children’s fundraising efforts, patriotic poems and songs to sing together, moral fables and tales of heroism.

Children were encouraged to write poems, letters and draw pictures for those stationed in on the front lines. By reading letters written by children, we see that they had a strong grasp on what was going on in Europe and beyond. They were in touch with world events as loved ones often discussed these matters openly in front of children.

Local newspapers encouraged children to send in their work and published it in regular columns. In the Dudley Herald, a newspaper in England, Ethel Cole’s poem “My Daddy’s a Soldier” was published for its readers on the 13th of February 1915:

I don’t know much of fighting,

And I’ve never seen a sword

But Daddy’s gone and left us

And they say he’ll get reward.

But, oh me the house is lonely,

And poor Mother’s awful sad

She’s one pleasure, now, one only

And it’s me now we’ve lost Dad.

Dad they tell me is a soldier.

And he ought to go and fight;

And our neighbours say he’s plucky

And I’m sure he’s going right.

But oh dear, we do so miss him

And poor Mother sits and sighs

And I know she’s very troubled

By the tears in her eyes

-By Ethel Cole, 146 High Street, Dudley

Girl Guides during WWI, via BBC.

During the war, members of the Guides fulfilled important wartime tasks, such as carrying important messages and helping deliver milk. Guide activities started to include first aid and learning to send messages using small flags.

Guides would also raise donations for the war effort, coordinating the sending of care packages and organising their own knitting and sewing sessions.

They may have even been used by the British Security Service to pass secret messages during wartime, inspiring girls like 14-year-old Audrey Hepburn, who acted as a messenger for the Belgian resistance during World War II.

Sport became an important part of the school day, with government ministers wanting to prepare young people for active service.

Sport became an important part of the school day, with government ministers wanting to prepare young people for active service.

Schools allocated extra time for sports.

Children spent some of their spare time playing football, hockey and other sports on parks and common land.

Due to the majority of fit young men being on the front, a large gap was created in sport and entertainment. Young female munitions workers were encouraged to play to keep their morale up, and quickly were used to keep the general population’s morale up by playing public sports.

The greatest goal scorer England had ever seen, Lily Par, began playing during WWI — and would score over 1,000 goals during her 31-year career. Sadly, in 1921, many football grounds banned women from playing.

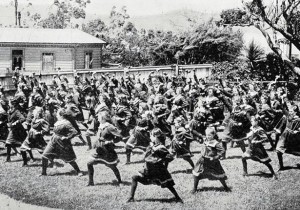

Wellington High School Girls Drill Class, ‘Keeping children healthy’, Ministry for Culture and Heritage, updated 22-Sep-2015

Schools adopted a nationalistic, patriotic focus, with the expectation of all to support the nation’s troops included in lessons.

One commonly held belief during World War I was that if children undertook physical exercise this would lead to better school performance. Particularly, in New Zealand schools, there was a strong emphasis on outdoor life and sports. Children were taught out of doors as much as possible, with running, swimming and athletics a key part of their education.

During the war girls were taught sport at school. Many had a lesson called “drill”, the equivalent of today’s “Physical Education” lesson. These mainly consisted of marching on the spot, stretching and swinging large wooden clubs around as a strengthening exercise.

Music

Music can make us happy or sad, calm and soothe us, or even recall a specific moment with our loved ones. Even though music wasn’t as accessible 100 years ago as it is today, it still had a great effect on people. And it was very useful during wartime. Music was used for pleasure, for morale and as a propaganda tool before conscription was introduced in Britain.

Classical composers were the rock stars at the turn of the nineteenth century. But to be able to listen to classical music with a full orchestra was reserved to those who could afford it. Even a simple gramophone was extremely expensive, so not everyone was able to listen to records in the comfort of their own homes. And radios as we know them were not yet invented. Those without played homemade instruments or sang to their heart’s content.

American enrolled ‘Yomanettes’ during ‘Happy Hour’ at US Navy Yard, Mare Island, California in c.1918. WikiCommons.

…for Pleasure

The rock stars of the time were composers such as Ralph Vaughan Williams and Ivor Gurney who were inspired by the English countryside and folk music. However, these gentlemen joined up to fight for the war effort, though some would continue composing. Unfortunately, it was still rare to find a woman in an orchestra at that time. In fact, during 1916, only 8 women were included in The Hallé’s records show, and by 1920, the orchestra was back to being fully dominated by men.

With limited modes of entertainment, many households relied on musical instruments to pass the time, especially in the evening. Women used music in their new roles, with nurses providing musical instruments for their injured charges. For women who had successfully enrolled within the armed services, music offered a way to boost morale, bring a division together and wile away the long evening hours.

…for Morale

Music played a very important role in war to raise morale. However, this wasn’t something that those in the war office were behind at first.

Within Girl Museum’s Heroine Quilt, there is a woman who fought policies to prove that music was and should be used to help men on The Front. With pure grit and determination, she arranged entertainment road shows for the troops to lift their spirits. Can you find her?

During the First World War, music was more upbeat than later wars, with songs like ‘Pack up Your Troubles in Your Old Kitbag’ and ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’.

Some classical composers felt passionately about writing music that would embrace and encompass feelings of mourning their loved ones, commemorating their lives, to celebrating when they came home, and to keep their spirits high when they were away. ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’ was aimed at all the families left on the Home Front. ‘Pack up Your Troubles in Your Kitbag’ gained huge popularity because of how it was easily accessible via sheet music that could be played on any piano.

Click on the media files to listen to some WWI favorites:

Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag

It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary

Till The Boys Come Home

…for Propaganda

Women were most effective with music as propaganda in music halls. Theatre halls were accessible for most people, unlike classical music concerts, so they were popular entertainment venues. In London alone, there were more than 300 musical theatres. These ranged from posh halls in the West End to smaller places in the East End. Music halls also doubled up as places where men of all fighting ages signed up to join the war effort. Vesta Tilley was nicknamed ‘Britain’s Greatest Recruitment Sergeant’. Here, a young woman named Kitty Eckersley recalls the moment that her husband was recruited by Vesta.

Vesta was draped in a Union Jack, singing “We Don’t Want to Lose (But We Think You Ought To Go)” amidst the audience, and by the end of the song there were so many men following her that there wasn’t enough room on the stage for all of them. It’s hard to imagine the true power of this popular recruitment tool, which appealed to their patriotism. There was also a darker side to this; men who refused were sometimes given a white feather, which was a sign of cowardice.

The clip at left, from the film “Oh! What a Lovely War”, gives us an image of what it could have been like.

Doing Their Part

Before World War I, most women across the world did not have the vote; they were paid less than men and certain jobs were considered inappropriate for them. In the UK, the vast majority of working class women worked as domestic servants or in factories, offices and shops. Women in less industrialized countries, such as Russia, France and Germany, predominantly worked the land. Many were not expected to engage in paid work after marriage.

However, the war required women to take on a variety of jobs. There was initial resistance for hiring women, but conscription made the need for women workers urgent, thus changing the workforce forever. In Britain, 2 million women replaced men in their jobs during the war. In Russia, the percentage of women in industry increased from 26% to 43%, and a million women joined the workforce in Austria. In France, the percentage of women in the workforce increased by 20%.

In contrast, in Germany, fewer women joined the workforce during the war. A large part of this was because trade unions were afraid women would undercut men’s jobs. These unions were partly responsible for forcing the German Government to turn away from moving women into work. Many female labourers were volunteers, leading to a smaller proportion of women entering employment in comparison to other countries. It has been suggested that not encouraging women into work played a contributing factor to Germany’s loss in the war.

Click through the tabs below to learn about the different roles women played in the workforce during World War I.

These farmerettes are harvesting a peach crop on a farm near Leesburg, VA, in August 1917. The farmerettes are wearing the regulation bloomers and smocks and are ready to march into the Virginia peach orchard. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

In France, Germany and Russia, many women already worked on the land. With the loss of male workers, their workload increased dramatically. As the war progressed, farm animals were requisitioned by the army, leaving women labourers to plough the field by hand. Many countries suffered food shortages and famine.

In the UK, the majority of women worked in towns and cities, so women and girls were asked to volunteer to work the land. The Government invited women to join the Women’s Land Army, an organisation that offered cheap female labour to farmers. From 1914 to 1918, the number of women working as farm labourers doubled. The 260,000 volunteers that made up the WLA were given a uniform and ordered to work as hard as possible in manual agricultural labour.

Women in the U.S. also responded to government posters to support the troops through food production. For some, agricultural work would have been a very new and difficult experience. But it also offered young women an opportunity to meet new people and, perhaps for the first time, experience independence.

Interior of a ward on a British Ambulance Train in France, via the National Library of Scotland.

Until 1916 many of the nurses were unpaid, so they mostly came from wealthier families who could support them. These were powerful women who became quickly versed in the management of military hospitals. Women as far afield as Australia and New Zealand volunteered to go to anywhere that needed them, including makeshift hospitals on the front. In Southeastern Europe, many women served as medical staff, including Queen Marie of Romania, who trained as a nurse and set up various hospitals within Romania.

Due to their close proximity to the war, nurses and doctors were injured and killed while tending to the wounded and while travelling to and from sites. In Britain, 45 nurses were killed and over 200 were decorated for their services to the nation.

Flora Sandes in uniform, about 1918. Via Wikimedia Commons.

From 1917, the British and American armed forces allowed women to enlist, but only men were officially allowed to go into battle. Women were recruited to free up men occupying non-combat roles. The British army established the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRNS) and the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF), who carried out support duties. Many of the women who enlisted in the U.S. undertook clerical work, and while French women were not given military status, they too contributed to military duties.

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Maria Botchkareva, a 25-year-old peasant woman, formed a battalion of women. Over 2,000 women volunteered to form the ‘Battalion of Death’, fighting side-by-side with Russian men. Bochkareva was wounded and decorated several times.

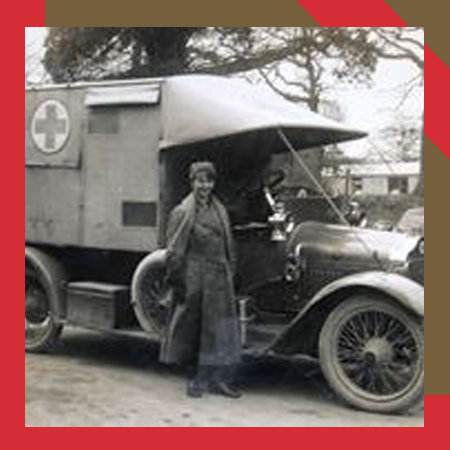

In Serbia, Flora Sandes joined the Serbian army as a soldier in 1916. She was initially an ambulance driver on the Eastern Front. When she enlisted with the Serbians, she was allowed to serve on the front lines and, by 1916, was promoted to Sergeant Major. After the war, she stayed in the army and became a Major.

Women were also used as spies, particularly in countries that were occupied by military forces. Nurses and other women working on the front were also inadvertently involved in military operations, hiding troops during invasions and lying about information that they had gathered during their time with the soldiers.

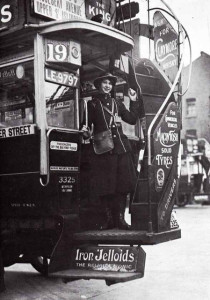

Tram conductress – a ‘Clippie’. Photo uploaded by Paul Townsen on Flickr.

One of their main responsibilities was to maintain discipline and monitor the behaviour of women around factories and hostels. They carried out inspections of women who worked in factories to ensure that they didn’t take anything into the factories which had the potential to cause explosions.

Women also began to work in the transport industry and were given positions such as bus conductress, ticket collector, porter, carriage cleaner or bus driver. The number of women working on the railways increased from 9,000 to 50,000 during the war.

After the war, many of these opportunities became closed to women as servicemen returned to their jobs. This was a common story for many professions after the end of the war.

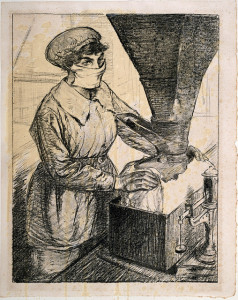

‘On munitions – dangerous work: packing TNT’, Archibald Standish-Hartrick, 1917. Photo via Archives New Zealand.

After 1915, a large number of women began to work in munitions manufacturing as the need for shells increased. By 1918, almost one million women were employed in some aspect of munitions work.

However, factory work was monotonous – women often found themselves doing jobs that had been simplified into a series of unskilled tasks. Working in munitions was relatively well paid, especially for women who had previously worked in domestic service. However, women workers in munitions factories were still paid as little as half the wages of men doing similar jobs.

Working in munitions factories often meant long hours and unpleasant or dangerous work. There were several devastating explosions in which women workers were killed. There was also little work/life balance. In order to keep up with the pace of demand from the front line, twelve-hour shifts were common and some women would work thirteen days in a row. However, the government did not provide a nursery provision for women working in other fields of work: this meant that they women had to rely on friends and family to help with their childcare.

Poster of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) for the elections to the Weimar National Assembly in 1919.

Old ways began to reassert themselves as newly unemployed women were pressured into becoming domestic servants or to marrying. However, there were some positive outcomes. During the war, many women developed new skills, self-confidence and contacts as a result of their jobs. The status of women fundamentally changed and would continue to do so throughout the rest of the 20th century.

Women in many countries had been fighting for the right to vote before the start of the war. By the war’s end, only Finland, Norway, New Zealand, parts of Australia and a couple of American states had granted female suffrage. Between 1917 and 1920, women gained the vote in Austria, Belgium, Britain, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Poland, Russia, Scandinavia, Sweden and the United States. World War I changed patterns of work for women, broken down barriers between the home and the world outside, disrupted the class system, and offered women from across the globe new opportunities and experiences.

Podcast

How did girls’ experiences of war change between WWI and WWII?

This lingering question was something we explore in our two-part podcast. The first explores girls’ lives in the Allied countries, and the second part explores girls lives in Axis countries & as persecuted Jews. Explore more girls lives by subscribing to GirlSpeak on Podbean or iTunes and clicking “Subscribe.”

The Girls of World War I

Below are the stories of incredible girls and women whose lives were forever changed by World War I. Click their images to discover their stories.

Flora Sandes

Flora Sandes (22 January 1876 - 24 November 1956) was a very interesting woman in the First World War. Although she was British, she enlisted into the allied Serbian army and consequently was the first British woman to fight as a soldier during the war. Flora was born...

Rosa Luxemburg

During WWI, Germany was having complex political problems on its home front. We don't often hear much about German women during the war, but Rosa Luxemburg (5th March 1871 - 15th January 1919) was a heroine, standing up and dying for her political views in Germany....

Mairi Chisholm

Thoughts of the First World War often conjure up images of men in the trenches, fighting over no man's land, and men travelling in ambulances, cars, or motorbikes. However, men were not the only people who utilized motorbike transport during WWI. The Women's Royal Air...

Helen Fairchild

Helen Fairchild (November 21, 1885 - January 18, 1918) was an American nurse who served as part of the American Expeditionary Force. Like many brave women who went to the frontline, Helen put her life on the line to help the soldiers injured in combat. For America,...

Alice Isaacson

Alice Isaacson was born in Ireland in 1874 and emigrated to America with her family shortly after her birth. Alice received her nursing training at St. Luke's Hospital, Iowa and the Chicago Lying-In Hospital. Until the start of World War One in 1914, little is known...

Marietta Victorina van Aerde

Marietta Victorina van Aerde was born on the 2nd December 1888 or 1889 to Frans Joename van Aerde and Celestine van Aerde. Marietta was the eldest of five; Marietta, Terese, Seraphine, Pauline and little brother Alexander. Little is known of the van Aerde children's...

Aileen Cole Stewart

In 1917, Aileen Cole received her nursing certificate from Washington D.C.'s Freedman Hospital School of Nursing. At this time Cole did not think that she would be sent to the front in Europe to serve as a nurse, as many other American woman had. Instead, she thought...

Edith Wharton

When war broke out in 1914, American novelist Edith Wharton (January 24, 1862 - August 11, 1937) didn't even think about going home or to England, she wanted to stay in Paris to help the many refugees coming from Belgium. Edith was born in New York City in 1862 and...

Margaret Maule

In a University in the Scottish city of Dundee, researchers found a battered old suitcase containing WWI memorabilia belonging to a mysterious nurse called Margaret Maule. The researchers looked through her belongings, which contained photographs, letters, autographs,...

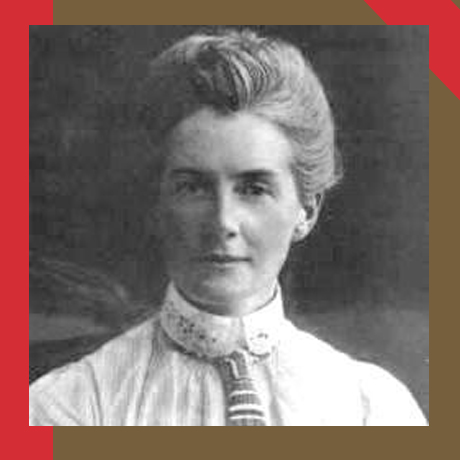

Edith Cavell

Edith Cavell (4 December 1865 - 12 October 1915) was a British nurse during the First World War who was living in Brussels, Belgium. A compassionate woman who didn't see the difference between allies or the enemy, she cared for humanity as a whole. However, it was...

Ecaterina Teodoroiu

Ecaterina Teodoroiu (15th January 1894 - 22nd August 1917) was a heroine in Romanian history for her acts of bravery and patriotism during the First World War and for the sacrifice she made for her country. Romania had entered the First World War on the allied side...

Milunka Savic

Milunka Savić was born on the 28th June 1888 in the Serbian town of Koprivinica. Little is known of Milunka's childhood, however we do know she had a brother, Milun Savić, as in 1912 she joined the Serbian army in her brother's name to fight in the Balkan Wars....

Deborah Pitts Taylor

Deborah Pitts Taylor (1893 - 25th April 1979) was a New Zealand ambulance driver in England throughout the First World War. During the war there were three general hospitals just for New Zealand troops, in Brockenhurst (where Deborah was), Walton on Thames, and...

Lena Ashwell

Lena Ashwell (28 September 1872 - 13 March 1957) is different from many of our other heroines in that she was not a nurse, nor a soldier, but rather an entertainer. Sounds strange right? But the First World War was the first war that entertainers mobilised to go to...

Vida Goldstein

Vida Goldstein (13 April 1869 - 15 August 1949) was born in Portland, Victoria, Australia in 1869. Surprisingly, her father was an anti-suffragist and her mother was a dedicated one, however he always taught his daughters how to be economically and intellectually...

Major Alice Ross-King

Alice Ross-King was born in Ballarat, Victoria on 5th August 1887 to a family of Scottish descent. Tragedy struck the Ross-King family in the early 1890s when Alice's father and two brothers drowned in an accident, leaving just Alice and her mother. Succeeding this...

Marie Marvingt

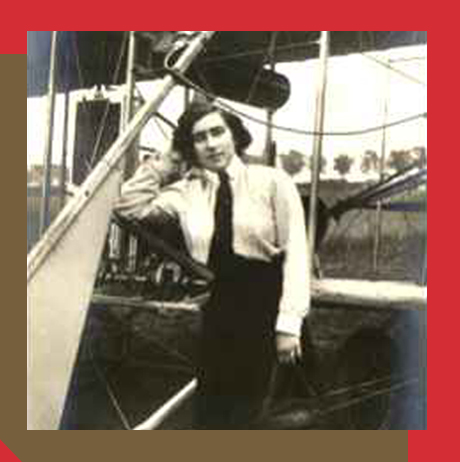

Outside of France, the name of Marie Marvingt does not ring a bell in the ears of either WWI or aviation historians. However, the story of Marie Marvingt must not be ignored in the story of women in the First World War, as she is one of the leading pioneers in both...

Vera Brittain

In 2014, the film The Testament of Youth was released, which is an adaptation of the memoirs of Vera Brittain's first book, also titled The Testament of Youth. This harrowing memoir which was published in 1933, puts a perspective of how the First World War shaped...

Raicheal Bell Moran

When we think of suffragettes and the campaign for the right to vote in Europe between 1914 and 1918, we are often bombarded with photographs of Emmeline Pankhurst and her followers. This is not to demean the name of Emmeline Pankhurst, it is simply how history...

Maria Plozner Mentil

Maria Plozner Mentil (1884-1916) served in the Italian armed forces as a Carnic bearer. The Carnic bearers were women who were active in the First World War, along the front of the Carnia (a region in Northeastern Italy) carrying heavy baskets of supplies and...

Princess Eugenie Mikhailovna Shakhovskaya

Princess Eugenie Mikhailovna was born in 1889 close to the then capital of Imperial Russia, St. Petersburg. Little is known about Eugenie's early life, but it is recorded that her father was a Baron and owned several textile and fabric mills. There is no record of...

Edith Vane-Tempest-Stewart

Edith Vane-Tempest-Stewart (3 December 1878 - 23 April 1959), Marchioness of Londonderry, was an enigmatic and forward thinking woman for her time. During a period when women's political allegiances were linked to their husband's parliamentary views Edith sought to...

Marina Yurlova

Marina Yurlova was born in 1901 in the small village of Raevskaya in the Caucasus region of what was then Imperial Russia. Marina grew up amongst the horse-loving and sword wielding people known as the Cossacks. By the age of fourteen, Marina knew how to yield a sword...

Anne Tracy Morgan

Anne Tracy Morgan (July 25, 1873 - January 29, 1952) was born in New York in 1873 to wealthy philanthropist parents who inspired and encouraged both her love of travel and helping those less fortunate than themselves. This trend of philanthropy was consistent...

Nadežda Petrović

Nadežda Petrović (12 October 1873 – 3 April 1915) was born in Serbia in 1873, moving to Belgrade in 1884 to pursue her education. Nadežda graduated from the High School for Girls in Belgrade in 1891 and started work as an art teacher. However, she was not...

Émilienne Moreau-Evrard

Émilienne Moreau-Evrard (4 June 1898 - 5 January 1971) is known in French history as the Lady of the Loo. She was not a nurse, nor a soldier, but an average civilian trying to defend her own village. Émilienne was born in Wingle, France and moved to the village of...

Nora Pennington

The story of Nora Pennington and her contribution to the war effort is a prime example of oral history of the First World War. David Gleason, a school friend of Pennington, is quoted in Jacqueline Kent's work In the Half Light as saying, We began hearing a lot about...

Ettie Annie Rout

Ettie Rout (24 February 1877 - 17 September 1936) was born in Tasmania, Australia, but grew up in Wellington, New Zealand. Her acts during and after the First World War made her a heroine in the eyes of the French soldiers and was duly recognized with the medal of...

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Throughout history, black history has largely been ignored and unfortunately even during the First World War there was still much prejudice against black people. During the First World War, Alice Dunbar-Nelson (19th July 1875 - 18th September 1935) was a field...

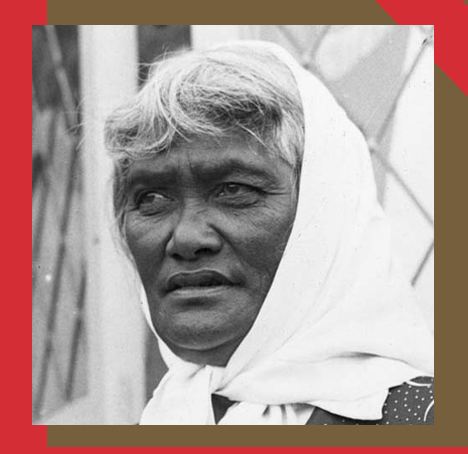

Princess Te Puea Herangi

Princess Te Puea Herangi (9 November 1883 - 12 October 1952) was a Maori leader in New Zealand during the First World War. She actively campaigned against the conscription of Maori men from the Waikato area due to her Grandfather, King Tāwhiao, proclaiming that no...

Emmeline Pankhurst

We don't really hear much about women's rights and activism during the First World War in Britain - just that women eventually got the vote. I can't say for sure why, was it that the government saw a country full of women working just as well as men or was it leading...

What did you learn?

Download our Girls in WWI Educational Guide for fun activities related to World War I. Designed for classroom or home use, this guide is aligned to US educational standards (which can also be adapted for use in the UK).

Credits

This year’s quilt is dedicated to all girls and women who have lived and died through wars not of their own making or design, but who contributed, participated and grieved as a result.

Special thanks to our curatorial and education team—Sarah Raine, Tiffany Rhoades, Rachel Sayers, Charleigh Powell, Mary Horrell, Emma Brynning, Lucy Palmer and Hillary Hanel—for such a wonderful job honoring these girls’ and women’s lives.

Additional Resources

Here are some of the sources we used to created this WWI Quilt. If you are interested in knowing more, have a dig through some of these very informative books and sites.

Fighting on the Home Front: The Legacy of Women in World War One by Kate Adie

Bawtree, Viola. ‘Episodes of the Great War 1916 From the Diaries of Viola Bawtree’, unpublished diary, 23/02/16-5/03/16. Ref.no: IWM DD 91/5/1.

Winners and Losers: Women’s Symbolic Rile in the War Story’. In Evidence, history and the Great War: historians and the impact of 1914-18 by G. Braybon.

Children’s Experiences of World War One by Stacey Gillis & Emma Short.

Anzac Girls: The Extraordinary Story of Our World War I Nurses by P. Rees

Nice Girls and Rude Girls: Women workers in World War I by D. Thom.

A Contemporary History of Women’s Sport, Part One: Sporting Women, 1850-1960 by Jean Williams

Children and World War I at the Library of South Australia

The Children’s War by Canadian War Museum

Schools and the First World War (New Zealand History)

Adlington, Lucy. ‘Fashion for the Few’, in Great War Fashion: Tales from the History Wardrobe (London; The History Press, 2013) pp. 33-51.

Patterns for the Great War by PatternVault

Why do we remember the poets and not the composers of WW1?

Great War Centenary (1914-2014) – Part 13: Music halls by John Lewis Stempel

Palace Theatre, Manchester: Vesta Tilley, the Music Hall Recruiter (audio)

‘World War One and Classical Music’ at the British Library

Women in World War One propaganda at the British Library.

Daughters of decadence: the New Woman in the Victorian fin-de-siecle at The British Library.

Women’s work in WWI by Striking Women

The Women War Workers of the North-West by Imperial War Museums

The Women’s Hospital Corps: forgotten surgeons of the First World War by J.F. Geddes