‘From Dark to Light’ is a metaphor for the progression from the Medieval to Renaissance period. We have been led to believe the Middle Ages were horribly dark, tragic times that suddenly changed into the light of the Renaissance. But history is far more complex than it seems. While some ‘dark’ things did exist, the reality was far more complicated – and far more female – than we usually think. Inspired by recent scholarship, our Heroines Quilt for 2018 brings the stories of Medieval and Renaissance heroines out of the “dark” recesses of history and into the “light” of popular imagination. Through their incredible tales and difficult lives, we hope to inspire a generation of girls to dig deeper and research further, proving once more that history is much like the future—female.

Medieval and Renaissance Girls

The girls and women in this exhibition span a time period of over 1,300 years: the Medieval period (roughly 400 to 1400) and the Renaissance (1300 to 1600), which overlapped depending on what region of the world you lived in. Over such a long period, girls’ experiences varied. Life for a girl was also different depending on her location, religion, class, and even her parents’ views on the roles of girls and women in society. So we have to be careful about making generalizations.

In some ways, Medieval and Renaissance girls led lives similar to girls in parts of the world today. They had a culture of their own with slang, toys, and games. They also made their own toys, such as cloth and wood dolls, boats from bread, and small houses from stones. And girls were cared for by their parents and guardians. In the tabs below, explore how life was similar and different for girls across Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

Europe

Head of a Young Woman, early 14th century, North French. Gift of John L. Feldman, 1994, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession No. 1994.518.1.

Once a girl turned 12, she became more of an adult and religion played a large part in how she was expected to behave. She could attend confession and take the sacrament of eucharist. The onset of menstruation was taken as a sign that a girl was ready for marriage. Yet marriage wasn’t her only option. Depending on her family’s wealth or class, a young girl might enter into service in a household or undertake an apprenticeship. She would learn crafts or a skilled trade, sometimes apprenticing for up to 10 years or until she was married. These skills included silkwork, embroidery, cloth making, or spinning, yet some did learn trades typically reserved for men. For example, the orphaned daughters of John Shaw, Alice and Matilda, are recorded as apprenticed to Peter Churche, a notary public. For girls of the upper classes, such crafts were taught as a way to advance her eligibility for marriage and may have led her to live with another noble family, learning alongside other children and forming relationships that might lead to marriage.

During the Renaissance, these attitudes about girls continued to evolve. Religion remained a central part of a girl’s life, dictating her duties and responsibilities in society. Upper class girls continued to be groomed for marriage, while lower class girls learned skills and trades to help their families survive or contribute to their own marriages. Apprenticeships became more common, as did representations of girls in art and literature.

Middle East

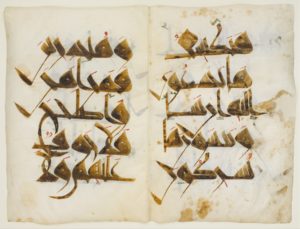

Bifolium from the “Nurse’s Qur’an” (Mushaf al-Hadina), ca. A.H. 410/ A.D. 1019–20 Islamic, Zirid period (972–1148) Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment; H. 17 1/2 in. (44.5 cm) W. 23 5/8 in. (60 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, James and Diane Burke Gift, in honor of Dr. Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, 2007 (2007.191) http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/456074

This lead to many improvements in girls’ status and lives. Upon birth, girls and boys were celebrated equally. A girl’s parents would whisper an adhan (a call to prayer) and the shahada (Islamic statement of faith) into her ear. Seven days later, when it was clear the girl would survive (as infant mortality was still high), a public festival was held to celebrate her birth and give her a name.

Until the age of 13, girls were not considered ‘sexual beings’, so their status was equal to that of young boys. They did not have to abide by social norms imposed on older girls and could play with other boys and girls. Around age 14, girls became ‘sexual beings’, yet even though there were some restrictions, many Islamic girls had freedoms their counterparts did not. Girls had the opportunity to become shopkeepers, artisans, textile workers, singers, musicians, and dancers. They experienced fewer legal restrictions that other girls during this time. Islamic girls could keep their surnames upon marriage, manage their own finances, inherit and bestow inheritance, and enter into contracts for marriage and divorce.

Within 200 years, the new faith and empire ushered in the Islamic Golden Age. Lasting nearly six centuries (from the 700s to the 1200s), this period witnessed scientific advancements, economic development, and a flourishing of art and culture that may have instigated the later European Renaissance. Several scholars and famous cultural figures during this period were girls and women, and 26 mosques were funded entirely by women through the Waqf (charitable trust) system. Some male scholars – such as mystic and philosopher Ibn Arabi – argued that girls could achieve spiritual equality with men. Others, like 12th-century Sunni scholar Ibn Asakir, wrote that girls should study and earn degrees in order to become scholars and teachers. There were no legal restrictions on girls’ education, so many attended classes or informal lectures and study sessions at mosques, madrasahs, and other public places. By the 15th century, so many women had become scholars that Al-Sakhawi devoted an entire volume of his dictionary to profiles of 1,075 female scholars!

Asia

Pillow in Shape of Reclining Woman, c. 12th-13th century, Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279 C.E.). Gift of Mrs. Samuel T. Peters, 1926. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession No. 26.292.82

One civilization that did have detailed historical records is China, where Confucian beliefs that centered on a patriarchal worldview were well established by the Medieval period. However, during the Sui, Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties, Buddhism and neo-Confucianism spread into China. For girls in the Tang dynasty (618 to 906 CE), society dictated that to be virtuous, one must act. This meant that girls’ actions were of the utmost importance, and several examples of xiaonu (“dutiful daughters”) were written into history. A girl’s virtuous actions included securing marriage alliances that spread Chinese culture, participating in war, become a court scholar focused on spreading ethical values, or working in trades (such as weaving, silk-making, tea shops, or seafood and drug stores) to help her family.

During the Song dynasty, girls’ virtuousness based on action continued to expand. Girls and women undertook a wide range of activities, such as running inns, midwifery, or becoming nuns or traders. Several women were well-read, including the Empress Xu who wrote Instructions for the Inner Quarters as a guide for other women. Empress Xu proposed that girls must be modest, sincere, honest, humane, respectful, loving, and warm. They should also be hard workers, frugal, and obey their husbands. Her instructions reveal that although girls likely had a lot of agency in having careers, they also still lived in a patriarchal society that dictated obedience to men.

China was conquered by the Mongols in 1290 C.E., and the two cultures were kept segregated from one another. Mongol girls were much more independent, often riding on hunts, fighting in wars, and advising on political and diplomatic matters. While this might have influenced some Chinese girls, the influence was limited. The Mongols were driven out of China only 100 years later, and Confucian ideals were reestablished – leading to an intensification of patriarchy.

Africa

Cast bronze head of a young woman, probably representing Queen Idia. The eyes are inlaid with iron, c. early 16th century, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria, Africa. The British Museum. Accession No. Af1897,1011.1.

In the Mali Empire, which peaked in the 1350s, sources say that men and women shared workloads. Girls would help harvest and process food, make pots and baskets, and tend livestock. Mali was also one of the most important trading centers in the world, and its cities featured vast libraries and Islamic universities. The Mali Empire was a semi-democratic government with one of the world’s oldest constitutions – The Kurukan Fuga of 1235 – so it is possible that girls enjoyed quite a bit of freedom in their lives.

For the most part, we do not know the status of girls in Africa during the Medieval and Renaissance. Individual accounts of girls and women help us understand that they did hold prominent places in society – but whether this was the norm is still debated. Sources are scarce, as sub Saharan Africa did not have written histories and didn’t become a focus for European exploration until the 1500s. And once Europe did fix its eye on Africa, it conquered many areas – erasing their history. European records that survive from this time present two conflicting views of Africans—either “dangerous and wild” or “law-abiding and punctillious.” We are still looking for voices of girls from this time period.

Girlhood in Depth: Life in Medieval England

By Tiffany Rhoades

Medieval childhood is a relatively new field of study. First recognized in the 1960s, the field now encompasses a variety of sources, including art, sermon lectures, ecclesiastical writings, poetry, literature, demographic records, letters, diaries, and city laws. Over the past forty years, these sources have revealed a wealth of new information about what children’s lives were like in the Medieval period—their triumphs and tragedies, their everyday habits and aspirations. Using the work of historian Barbara Hanawalt, which focused on medieval life in England, the following essay explores what life was like for a young girl, and reveals how our childhoods may be more similar to our Medieval counterparts than we could imagine.

Use the slider below to discover the different sources that help us understand Medieval Girlhood.

Medieval girlhood is a complicated subject. Until the 1960s, the topic of childhood in the Medieval period was largely ignored. It was thought there just wasn’t evidence for it, or that it couldn’t have existed since the Victorians supposedly ‘invented’ childhood. Fortunately for us, childhood in the medieval period is now a recognized field of study – and no one is more versed in that study than historian Barbara Hanawalt. Using her vast research, we can put together a picture of a Medieval girl’s early years – her triumphs, her tragedies, and her everyday habits that formed the basis for who she would become in society.

In order to explore a girl’s daily life, we first need sources. Fortunately, the Medieval period has a wealth of different kinds of information including art and archaeology, hagiography, coroners inquests, letters, laws, apprentice contracts, and training manuals. By looking at each of these sources, we can piece together a girl’s typical day.

Cassone, c. 1345 – 1354 (made), Florence or Siena, Italy. Currently held by the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Saint Agnes by Domenichino, c.1620, Oil on canvas, Royal Collection, Windsor. WikiCommons.

Our third source, coroners’ inquests, confirms hagiography. Coroners’ inquests were written when a death occurred, as medieval law often required that at least one coroner or juror attend a death and record its circumstances in an inquest. These inquests a unique source, in that they span almost all social classes,so the picture they paint is a much more universal one than other sources. Many show the activities of home life, family structures, and emotional relationships. In looking at inquests as a whole, a few patterns emerge. First, the nuclear family unit—a mother, father, and children—was the predominant family structure in medieval society. Extended families living together only included either a father’s mother living with the nuclear family, two brothers or two sisters living together, or single parent households with young children. Second, we get vivid descriptions of medieval homes. As Barbara Hanwalt explained,

“They had courtyards with walls or ditches surrounding them and wells and ovens within. There would probably be two rooms and often two floors. The floors, covered with straw, were highly flammable, as were the straw pallets used for beds. The main room contained a raised hearth in the center of the floor. The child spent the first years of life in a cradle near the fire. Also around the fire were pots, pans, and trivets. Tables, chairs, and beds were the only other furniture mentioned. During the day the open door provided light and children and animals wandered through freely. At night candles were used, which seem to have been left to burn all night, sometimes catching the houses on fire. In the city the child was raised in a shop or tenement, the construction of which was better than wattle and daub, but they burned easily nonetheless.” (Hanawalt, “Childrearing”)

Finally, coroners’ inquests reveal where young girls grew up, including the activities that they engaged in. For newborn and infant girls, life consisted of her home. Up until the age of 3, girls followed their mothers around the home, thus their deaths often occurred either in the cradle or in imitating their mothers by playing with pots and pans, gathering food, or doing laundry. This shows that girls began helping in household labor early, though perhaps only as imitators – much the same way young girls today might pull out pots and pans to bang on them, or have play vacuums to clean the house.

Once girls reached the age of three, the inquests reveal that girls took a more active role in the household economy. Accidental deaths move from ‘play-acting’ to actually helping their mothers in and around the home. These deaths include pulling hot pots off trivets, playing with knives or cooking, falling into wells and ditches near their homes, or having accidents on the property of neighbors, village greens, or in bodies of water while playing. Thus, from the ages of 3 to 7, it seems that girls began to receive both chores and more autonomy. They worked in the home, but played with other children in communal spaces.

After age 7, accidents move into more adult activities, like playing games similar to household chores, gathering wood and working in the fields, and work-related accidents. Until the age of 14, it seems that girls’ lives consisted of additional chores,slowly scaling up based on their age and maturity. This demonstrates that adults recognized the physical and psychological limitations of children and adolescents, so much that they did not want to risk injury or death by giving girls tasks beyond their skills, much as we still do today.

Another source, letters, confirms coroners’ inquests and adds another dimension to children’s deaths: grief and love. Many letters show a highly emotional response from parents whose children died, including fathers in the upper classes who often recorded their tears, cries, anxiety, tearing of hair, and falling down with grief. The author of the poem “Pearl” describes a father’s reaction upon the death of his daughter, Margarite:

Before that spot my hands I clasp’d

for care full cold that seized on me;

a senseless moan dinned in my heart,

though Reason bade me be at peace.

I plain’d my Pearl, imprison’d there,

with wayword words that fiercely fought;

though Christ Himself me comfort show’d,

my wretched will worked aye in woe.

These letters also show that neighbors were more important than extended family: most hagiography, inquests, and letters show that parents and neighbors were responsible for watching after children and were the first to react to accidents and deaths.

After the age of 14, a girl’s life could go in a variety of ways, and the law protected her in theory. Laws provided her with protection should she be orphaned, requiring her to go to court with an account of her parents’ property, and the court would arrange a wardship for her. Additionally, some cities like London regulated the quantity, quality, price, and distribution of basic necessities so that children had access to what they needed most: water, bread, meat, poultry, eggs, fish, shellfish, cheese, candles, and charcoal.

The age of 14 was also when a girl could be formally apprenticed in a trade. Girls were typically apprenticed to makers of silk thread, dressmakers, or embroiderers. All of these trades they could continue after marriage. Additionally, some cities did allow married women to carry on their own businesses, contract their own debts, and settle their own legal cases. So an apprenticeship was very important to a young girl, allowing her to learn a trade in which to support herself and her family, as well as increase her value in marriage since she could contribute to the household economy. Girls who became apprentices might have married, while others became servants.

Servants also had a fair degree of autonomy. They could accumulate wages for a dowry or to open their own independent shop. Some girls entered service for life, but many records indicate that becoming an apprentice or servant was just a stepping stone to increasing a girl’s value in marriage and enabling her to support herself. In some cases, becoming a servant also led to a relationship of loyalty and trust with a girl’s master, who might fund her dowry or shop, or leave her property upon his death.

There are a variety of other sources the reveal even more about girls’ lives in the Medieval period. Training manuals for new parents included lessons for young children on morality and personal habits. One manual described a girl’s morning rituals, which included waking at 6 a.m.; sponge bathing and brushing her clothing; cleaning her shoes, hair, nails, and teeth; greeting her parents at breakfast; attending mass or school; playing before her midday dinner; returning to chores or play; and having leisure time in the evening. Additionally, criminal records show that crimes against children did occur. For example, the beggar Alice de Salesbury was found guilty of kidnapping young Margaret Oxwyke and forcing her to beg as well. Others show that molestations of girls as young as 5 also occurred.

One topic on which most sources are silent is puberty and menstruation. Since the majority of sources were written by men and menstruation was considered an ‘unclean’ topic, this is not that surprising. Menstruation also had little to do with marriage, since marriage was more a legal aspect than a biological or social one. While moralists and cautionary tales about sexual activity abounded, so did sexual innuendos (such as those written by Chaucer). The view on sex is ambivalent at best: we don’t fully know, but it sounds very much like our society today – it depended on what you believed. There is, however, an abundance of stories about both voluntary and forced sexual initiation of young women. These accounts also tell us that sexual initiation did not change a girl’s status from ‘maiden’ – only marriage did. In cases of rape where the girl could successfully argue it (with the help of friends or family), she was compensated.

Overall, medieval sources reveal that girls’ lives were more like our own than not. Part of this is likely biology sincewe still develop and mature in very similar fashion to girls in the medieval period. Yet the other part is cultural. Many of the basic premises of childhood development were formed in ancient times and continued through the medieval period to today. Yet for centuries, scholars have denied that our childhoods were in any way similar—partially because we view anything labeled ‘medieval’ as undesirable, and partially because the sources have long been silent. Thanks to the work of historians like Barbara Hanawalt, we have begun to piece together the complex and strikingly similar lives of young girls in the Medieval and Renaissance. My hope is that we continue to do so, and one day see a fascinating glimpse into the real childhoods of the heroines portrayed here.

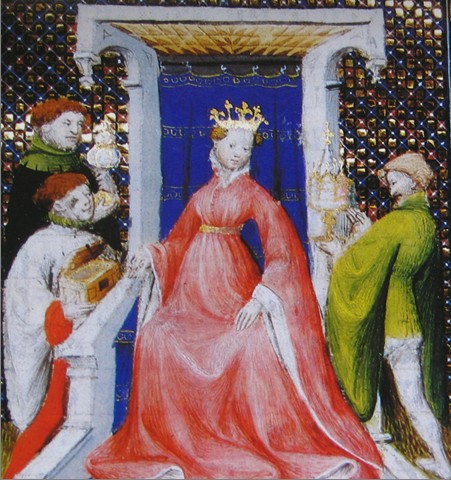

Reactions to Female Rulers in the Medieval and Early Modern period

by Danielle Triggs

The Medieval and Early Modern period was a hard time to be a woman, even if you were higher up in the social chain. High born women were often used as pawns by their male family members to forge alliances. Despite this, some women – through a mixture of timing, talent and luck – had the opportunity to rule during this period, although it varied from country to country how these women achieved their power.

Under Salic law in France, a woman could not inherit the throne, nor could her male descendants. While this law was originally created in the 5th century concerning communal land inheritance, it wasn’t used until much later as a way to prevent monarchical inheritance claims. It was used against Edward III of England when he tried to claim the French throne through his mother Isabella of France. Yet while a woman never sat on the throne of France, several women did hold power as regent on behalf of their sons. These women included Blanche of Castile, Catherine de Medici and Marie de Medici. Additionally, Anne de Beaujeu was regent on behalf of younger brother, Charles VIII. Interestingly – apart from Anne – none of these women were French and ended up ruling France as a regent. As the wives and mothers of French Kings were often foreign, the marriage being used to create an alliance, this meant more foreign woman have ruled France than French, because the only opportunity is through regency.

In the Early Modern period the Habsburg family had an Empire stretching over what is now Spain, Austria, the Netherlands, parts of Italy and Germany, had a tradition of giving female family members the regency of the Netherlands. This was under the assumption that they would always respect the overarching wishes of their male family members. Margaret of Austria was twice widowed at a very young age, and after her second husband died, she returned to her family and began to act as regent for her nephew, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles’ empire included Austria, Burgundy, Castile, Aragon, and lands in the New World. He found it wearying to rule over so much land and liked having a family member whom he could trust to rule in his interests in the Netherlands. This tradition continued when Margaret’s niece (and Charles V’s sister) Mary of Burgundy, who was also widowed young, became regent of Netherlands after the death of her aunt. Mary helped raise her young niece, Margaret of Parma (who was the illegitimate daughter of Charles V), who then succeeded her as regent of the Netherlands for Philip of Spain.

Meanwhile, in Spain, the issue of female inheritance was more complicated. During this time, Spain was two separate nations: Castile and Aragon. While Castile allowed a woman to rule in her own right, Aragon did not. When Isabella, Queen of Castile, married Ferdinand, King of Aragon, their marriage unified Spain. However, Isabella – ruler of the significantly larger and richer section of Spain – was determined to rule Castile her way. Though she loved and respected Ferdinand, she didn’t allow him to make decisions for Castile. This created a lot of tension in their marriage, primarily because Ferdinand and Isabella were cousins and if Castile had the same law as Aragon then Ferdinand would have been the ruler of both Aragon and Castile in his own right.

While England did not have a law which prevented women ascending the throne, they did follow the tradition of primogeniture, which meant that the eldest male son (or his children) would inherit. While women could technically inherit, it would generally only happen if she had no surviving brothers. Typically, if her inheritance and resulting wealth was significant, she would be given to a favourite of the King in marriage as a way of rewarding the favourite with land and titles.

An Independent English Queen

Part 1: Edith

With regard to Queenship, it wasn’t until 1553 that a woman sat on the throne of England. The path to England accepting a female ruler was a rocky one, and there are several times prior to 1553 when women came close to ruling the country independent of a male king.

In 978, shortly after the murder of King Edward the Martyr, the accession of his younger half-brother Ethelred was in jeopardy. Edward and Ethelred had their own factions supporting their right to rule, and after Edward’s death, his supporters looked to their half-sister, Edith, as a possible alternative. At this time, Anglo-Saxon society believed that a woman was not ‘throne worthy’ (called Atheling). As historian Elizabeth Norton noted, ‘as the popularity of Matilda of Scotland’s marriage to Henry I showed in 1100, in England women were known to be able to transmit royal blood and, potentially, a claim to the throne. Matilda was widely seen as an heir to the Anglo-Saxon kings through her mother, St Margaret who was a great granddaughter of Ethelred II.’ It is thought that the attempt to crown Edith over her half-brother Ethelred was due to the revulsion felt for the murder of Edward and because Ethelred was a minor at this time. Edward’s supporters tried to convince Edith to claim the throne and marry one of their choice (who would have been the real power in ruling rather than Edith). She refused, so we will never know if they could have succeeded having a Queen rule England so early in the Medieval period.

In this case, it is only due to the murder of Edward that Martyr that a faction of the nobles contemplated a female ruler. While Ethelred was too young to have been complicit in his older brother’s murder, his mother Elfrida was tarnished with the sin of murdering her stepson. With Ethelred being so young, and his mother being a strong individual who had wielded power in her husband’s time, it was clear she intended to be a source of major influence under her son’s kingship. In this case, Edward’s faction also assumed they could then pick Edith’s husband, who would be the true ruler, with Edith transmitting her sovereignty to her husband.

Part 2: Matilda

Possibly the closest England got – before 1553 – to a female ruling in her own right was in 1135, when Henry I died and left the throne of England to his only living, legitimate child: Matilda. Matilda’s brother William had died at the age of 17 in a shipwreck in the English Channel, leaving Matilda as the only legitimate heir. As Henrietta Leyser stated, ‘In 1127, what mattered more than gender was legitimacy of birth. In pre-conquest England, illegitimacy had not been a bar to the succession…Yet, within a generation…An illegitimate King of England had become unthinkable . Better a woman than a bastard; but better than either, it came to be thought, was succession by the eldest son.’ Ironically, Henry had at least 22 illegitimate children, including Robert of Gloucester, who would become one of Matilda’s biggest advocates.

While Henry made his barons pledge to support Matilda’s right to the throne, this all fell apart after his death. Henry had married Matilda to Geoffrey of Anjou, which caused disgruntlement from his nobles as Normandy and Anjou had historically been fierce enemies. Additionally, when Henry died in England, Matilda was recovering from an extremely difficult birth in Anjou (France) and was not able to quickly take control. This cost her dearly, and her cousin Stephen of Blois took the opportunity to seize the throne. Very little was done initially to stop Stephen, probably because ‘although there was no law barring female succession in England, neither was there any precedent, and the great barons were reluctant to support a woman’.

Once Matilda recovered, she assumed the fight to win her throne. This was the start of two decades of civil war referred to as The Anarchy. The end came when both armies were reluctant to fight, for they ‘had suffered nearly two decades of civil war and…realised that victory for either side in battle was likely to result in mass land confiscations and continued bitter divisions in the realm. The time for ceasefire had arrived’. By then, Matilda had let her eldest son, Henry, continue the fight and Stephen’s eldest son, Eustace, had died. Stephen and Henry came to an agreement that Henry would be named as his heir, and would inherit England on his death. So while Matilda did not gain the crown of England in her own right but her efforts did ensure that through her son that she was able to see her family line restored to ruling England. Her struggle also indicates that the English nobility at this time were more comfortable with a male teenager as their ruler than an experienced stateswoman.

Part 3: Elizabeth

Three centuries later, after the War of Roses ended in 1485, the victor Henry VII (from the House of Lancaster) married Elizabeth of York to symbolically unify the two houses and create a new English ruling dynasty. While Elizabeth had a stronger claim to the throne than her husband, as the daughter of Edward IV, it was never considered that she would share any power with her husband. Henry and Elizabeth had two boys; Arthur and Henry. Arthur died at the age of 15, leaving Henry as the heir. Henry knew the importance of continuing his family dynasty and spent a large part of his reign struggling with what to do if he couldn’t have son.

By the time of Henry VIII’s death in 1547, England had begun to contemplate a female ruler. Henry had left behind three children: the sickly Edward VI and two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. Edward’s reign only lasted five years, ending with his death at the age of 15. According to Henry’s will, if Edward was to die childless, then his elder sister Mary was to become queen; and if she was to die childless, their sister Elizabeth was to become queen. However, some of the nobles did not want the sisters to rule. All of Henry VII’s children had their own faiths: Edward was strongly Protestant, Mary was strongly Catholic, and Elizabeth was a Protestant with more tolerant views. As a result, upon Edward’s death, some of the powerful nobles did not want to return to Catholic rule under Mary.

These nobles advocated for another heir to the English throne: Lady Jane Grey, the granddaughter of Henry VIII’s youngest sister. Though Jane’s claim was significantly weaker than Henry’s own daughters, the Duke of Northumberland married his son to the Protestant Lady Jane Grey and had her crowned queen. Jane’s reign only last 9 days because Northumberland had underestimated the popularity of Mary (and the love the population had had for her mother Catherine of Aragon) and she was able to rally support and convince the privy council to switch allegiance to her. Mary’s reign lasted for 5 years before her death in 1558 and she left the throne to her younger sister Elizabeth as her father’s will dictated should she die childless.

What is interesting is that due to the lack of male relatives of the Tudors, the issue with Mary inheriting the throne was not her gender, but her religion. While Mary’s reign may not be considered a success due to her religious intolerance and her strong connections with Spain, the long and successful reign of her younger sister, Elizabeth, was undoubtedly a positive step for the acceptability (if not preference for) a female ruler. Elizabeth paved the way for future queens of England including; Anne (1702-1714), Victoria (1837-1901) and England’s current monarch Elizabeth II (1952- present).

Attitudes towards female rulers in the medieval and early modern period softened as time went on. Issues like legitimacy and religion became as important if not more so in some cases as to who was fit to rule. Women who had the opportunity to rule – even for a short time – and succeeded, helped make it more palatable in the minds of the people for future women to rule. In England a woman could only rule if she had no male siblings, however, in 2013 the Succession to the Crown Act altered the law from male preference primogeniture to absolute primogeniture, so that for the the new generation of royals the eldest child would inherit irrespective of the gender of them or their siblings.

Our Heroines

Much like today, attitudes towards girls in the Medieval and Renaissance varied. Parents around the world had vastly different views on how to raise their children, and the role of girls varied based on their culture and age. While we can never know exactly how the women in this exhibition were reared in their youths, their stories challenge us to consider that young girls were not just silent spectres. Instead, they were active in their families and communities, educated and trained according to their social station, and had mobility and agency all their own.

Knowledge about girls’ lives comes to us primarily from the stories of the women they became. These are our Heroines: girls and women who led remarkable lives that provide us insight into what girls could – and could not – accomplish during the Medieval and Renaissance. These girls hail from all corners of the world, showing that girl power had no geographic bounds. We hope their stories inspire you to pursue further study of these incredibly rich periods in history—and find the hidden tales of girls and girlhood waiting to be told.

Garsenda

Garsenda (c. 1180-1242) was a powerful countess of thirteenth-century Provence and Fourcalquier (now part of southern France). She was also a lover of art and music, a poet, and a generous patron of the artists in her court. Garsenda was born into a noble family in...

Queen Anna Nzinga

During the medieval period, the Ndongo and Matamba Kingdoms (in present-day Angola) had not yet been settled by Europeans, and were continually facing invasion by their European neighbors in the North. Anna Nzinga, who would come to rule the Angola territory, was born...

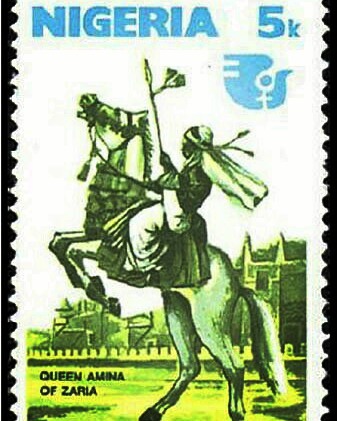

Amina Sukhera

When most people think of the medieval world, they imagine lavish European courts and iconic films like Monty Python and the Holy Grail, but cultures were flourishing in all areas of the settled world. While the most powerful European nations were sailing and...

Shangguan Wan’er

The most popular portrayal of the medieval period is of grand knights fighting on horses or (mostly white-washed) European populations suffering from the plague. But this depiction glosses over some of the most interesting people – and regions – of this era. Take...

Empress Wu Zetian

Empress Wu Zetian went from concubine to the only female ruling Empress of China in seventh century C.E. Unusually, Wu Zetian's father encouraged his daughter to learn to pursue an education. She learned to read and write. She also learnt to play music, write poetry,...

Hua Mulan

Hua Mulan is a legendary female Chinese warrior made famous by the "Ballad of Mulan." We don't know exactly when Mulan lived, as our main source is this Chinese ballad. However, we think she lived during the Northern Wei dynasty, which lasted from 386 – 534 C.E. Mulan...

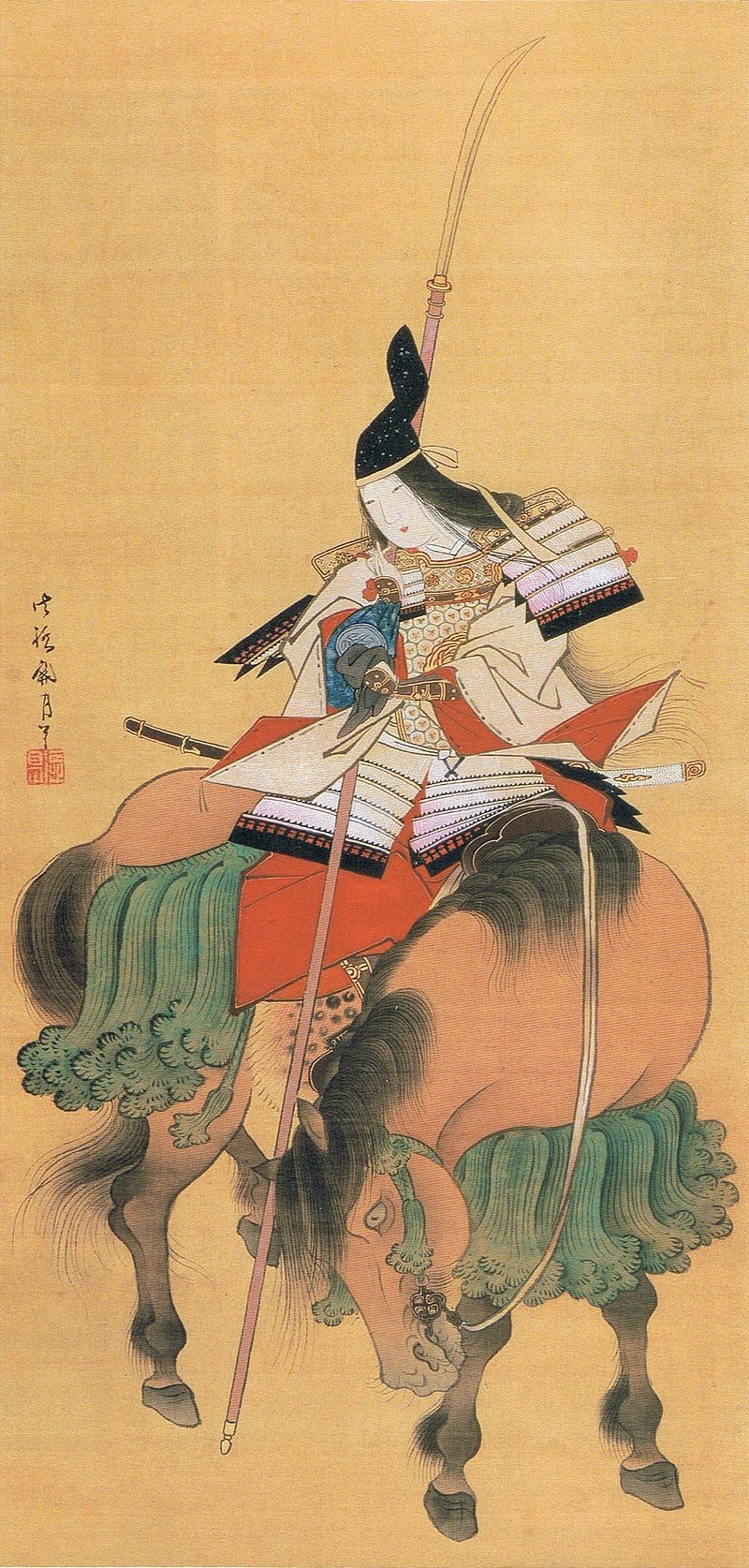

Tomoe Gozen

Tomoe Gozen was an extraordinary and rare female Japanese warrior who fought in offensive battles. Tomoe Gozen lived during a period of great instability in Japan. The Genpei War had laid waste to the country and the age of the samurai had begun. We do not know...

Taira no Tokuko

Taira no Tokuko was adopted by the Emperor of Japan, Go-Shirakawa, in 1171 at the age of 17. A year later she married the Emperor's fourth son, Takakura. This arranged marriage brought their two fathers-in-law together to support each other. Takakura and Taira no...

Hōjō Masako

Hōjō Masako was the wife of the first Shogun, or military dictator, of Japan. She held great power throughout her life and ruled from the background. Hōjō Masako was born in the Inzu province of Japan in 1157. She fell in love with her husband, Yoritomo, when he came...

Anna Comnena

Widely considered to be Europe's first female historian, Anna Comnena (1083-1153) grew up a princess of the Byzantine Empire. She was a strong and wilful woman who acted in a way that caused her male contemporaries and subsequent historians to feel a mixture of horror...

Melisende of Jerusalem

In the medieval period, Jerusalem was central to the aspirations of Western Europe and the Pope – to fight the ‘infidel’ for the Holy Land was the pursuit of Kings and the ordinary men alike. To rule Jerusalem in this period was a challenge for the most competent of...

Fatima de Madrid

Fatima of Madrid (10th or 11th century) is believed to have been an astronomer and mathematician, who worked, wrote, and contributed to astronomical knowledge in medieval Spain. Although some scholars recognise her as a historical figure, others are unsure whether she...

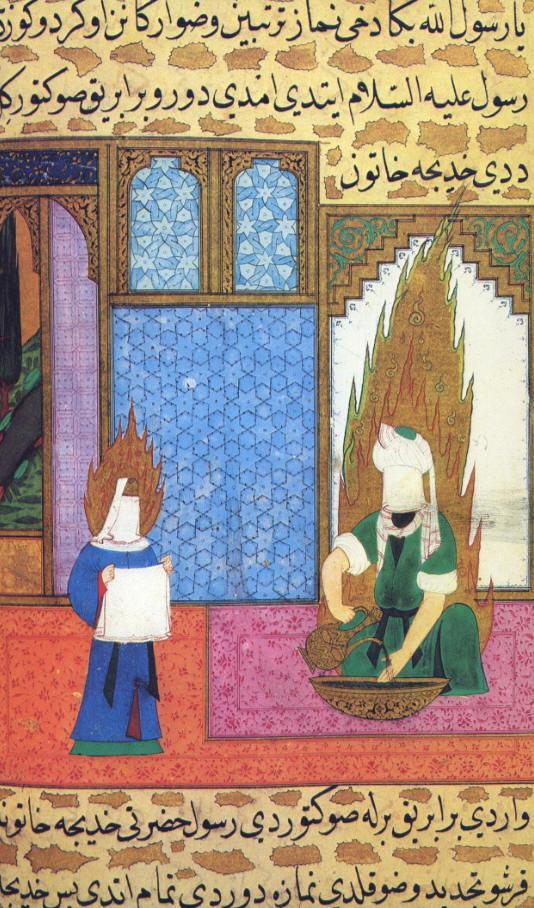

Khadījah

Khadījah bint Khuwaylid or Khadījah al-Kubra (Khadījah the Great) (c. 555 or 567 – 620 C.E.) was the first wife of the Prophet Muhammad, the central figure of Islam. As Muhammad’s first follower, she is considered the first Muslim and one of the most important women...

Empress Sophia

Remnants of the Byzantine Empire can be found on colorful mosaics and frescoes from the medieval period, and they do little justice to the opulence of the empire that dominated Eastern Europe in the medieval era. Sophia was the daughter of Empress Theodora’s elder...

Christina of Sweden

Christina of Sweden (1626-1689) was supposed to be a boy. Her parents, King Gustav II and Maria Eleonora of Sweden, desperately wished for a son who would be strong enough to rule Sweden. At birth, baby Christina was even mistaken for a boy; Christina’s aunt had to...

Francesca Caccini

Francesca Caccini was born on September 18, 1587 in Florence to Giulio Caccini, a successful Florentine musician. Her childhood was spent under her father’s musical tutelage, where she had the chance to showcase her talents in roles her father had written for the...

Elizabeth I of England

Born in 1533, Elizabeth I was the daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Before she was three years old, her mother was beheaded, and Elizabeth was declared illegitimate. She was mostly neglected by her father until his last wife, Catherine Parr,...

Mary I of England

Queen Mary I of England was the first woman to rule in her own right as Queen. She lived a difficult life as the daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon — their only living child born in 1516. During her childhood, Henry broke with the Catholic Church in order...

Catherine de Medici

The black legend that has surrounded Catherine de Medici (1519-1589) since her stint as regent of France for her three eldest sons has made her one of history’s most infamous women — poisoner, fan of the occult and the supposed mastermind behind the St...

Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (1480 - 1519) was a member of one of the most infamous families of the early modern period. The Borgia name is synonymous with poison, murder, and incest. While a great deal of the family’s reputation is earned, a lot of it is myth, spread by...

Isabella d’Este

Isabella d’Este (1474-1539) was the Marchesa of Mantua and a key cultural figure of the Italian Renaissance. She is known as a trendsetter and patron of the arts, popularizing fashions and art styles, but was also a political figure and ruled Mantua as regent for her...

Isabella of Castile

While Castile did not have a law banning women from succeeding the throne of Castile, Isabella (1451 - 1504) — one of the medieval period’s most famous queens — did not grow up expecting to rule her country of birth. She had two brothers, an older half-brother called...

Margery Kempe

During the medieval period, England was characterized by a deeply religious atmosphere. Communities’ social experiences were centered around following rules as written in the Bible and attending church as well as other religious ceremonies. Margery Kempe was born in...

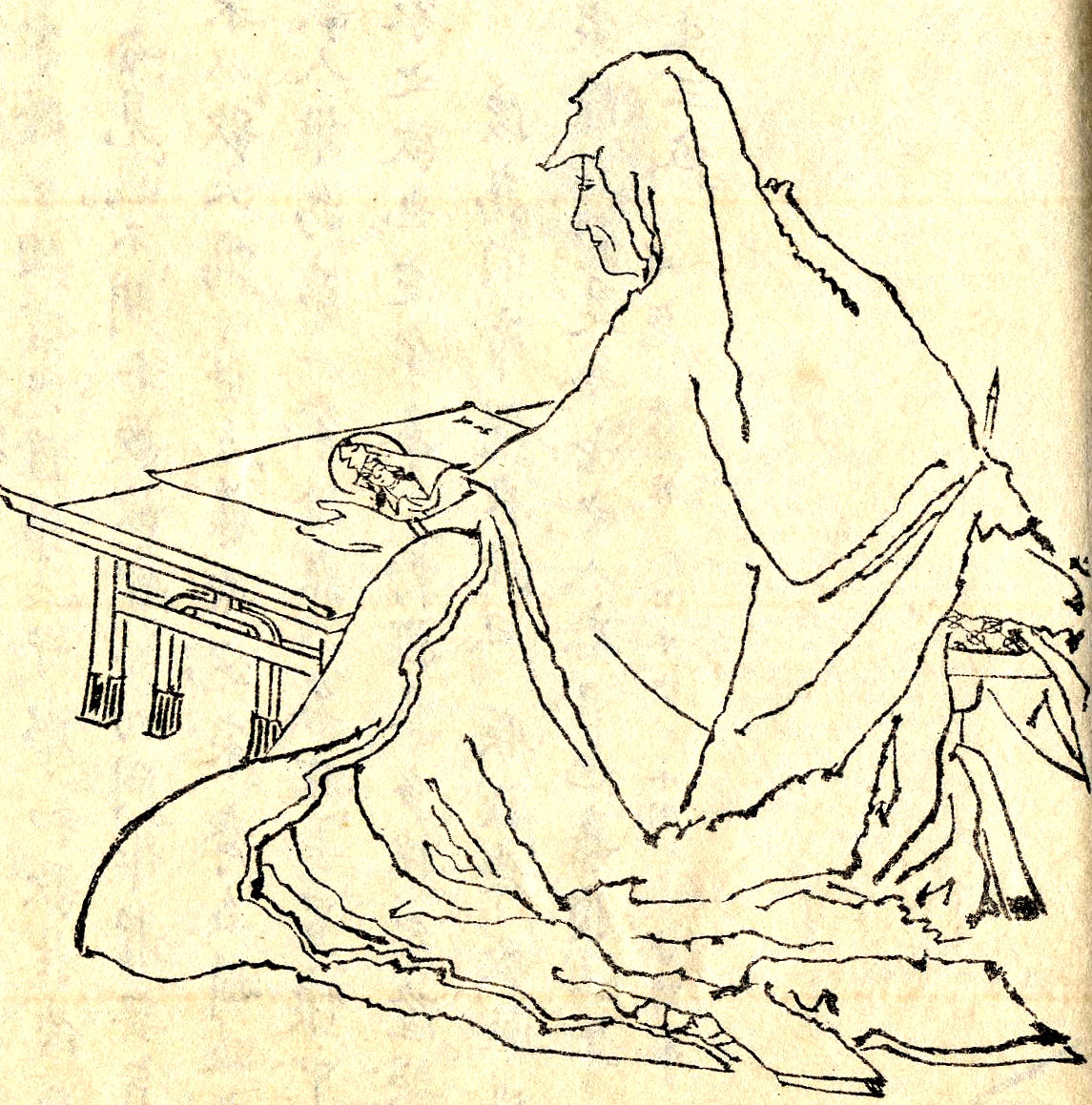

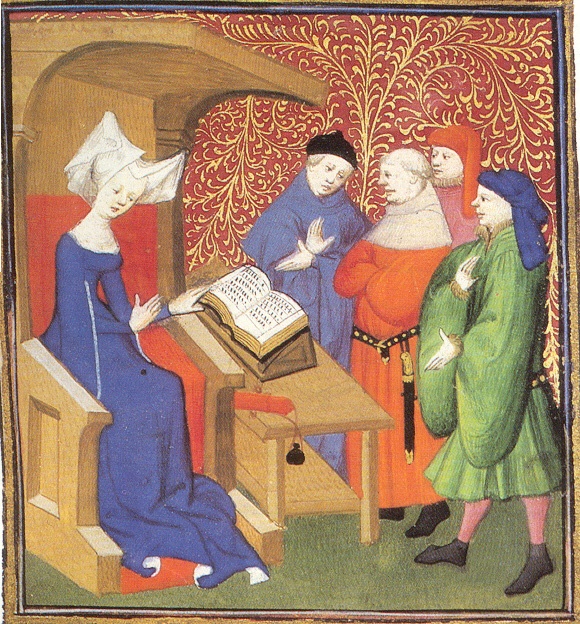

Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan (1365 - 1430) was an Italian writer at the French court during the Hundred Years War between England and France. She is considered the first professional female writer. Christine moved to Paris at the age of 5. Her father, Tomaso, had already moved...

Joanna of Naples

At just one year old, Joanna (c. 1328 - 1382) had a lot resting on her tiny shoulders: due to the untimely death of her father, she became heir to the throne of Naples. At the time, Naples was ruled by her grandfather, Robert the Wise. Joanna's life and reign...

Blanche of Castile

The daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile (part of present-day Spain) and granddaughter to one of the Medieval periods most infamous couple, Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, Blanche of Castile (1188 - 1252) certainly lived up to the legacy of her powerful...

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine (c.1122-1204) is considered one of the most powerful women in Medieval Europe, and became Duchess of Aquitaine at age 15. Due to her vast inheritance she was one of the most desirable women of her time, and the same year she inherited Aquitaine...

Matilda of England

69 years after the Norman Conquest, England was in again in crisis. This time it was because a woman had been left the throne of England, and England’s nobles were not happy with the concept of the unprecedented rule of a woman. Matilda (1102-1167 C.E.) was the...

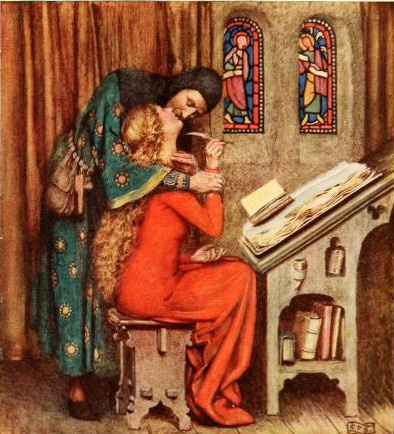

Heloise

Heloise (c. 1098 - 1163 CE) was a French scholar and abbess, who is famous for the love letters she wrote to her husband, Peter Abelard, from a religious convent. Heloise's birthdate and parents are a mystery to us. We know that she spent her childhood at a convent...

Hildegard of Bingen

Can you imagine being shut away from the world before reaching your teens? That's what happened to Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179 CE). Yet she emerged from a life of solitude to become one of the most educated women of the Middle Ages: a writer, naturalist, composer,...

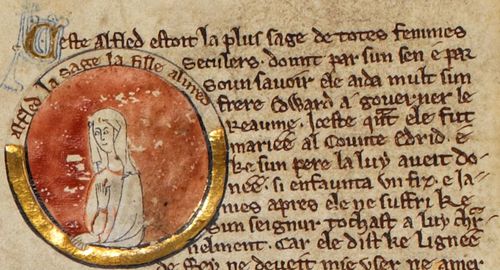

Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians

Aethelflaed (c. 870-918 CE) was the daughter of Alfred the Great, who was king of Wessex from 871 to 899. When she was a young girl, her father recaptured part of England from the Viking invaders who had conquered it. As a teenager, Aethelflaed married Aethelred, Lord...

Discover More…

Want to learn more about girls in the Medieval and Renaissance? Check out the resources below, then scroll down to read the incredible stories of real-life girls and women who we designated our Heroines of 2018.

Educational Guide

Download our Heroines Quilt V Educational Guide for fun activities related to the incredible girls featured in this exhibition. Designed for classroom or home use, this guide is aligned to US and UK educational standards.

Podcast

You can also discover more warrior princesses and their incredible queen counterparts in our GirlSpeak podcast series and other awesome podcasts. Click here to visit our Incredible Queens episodes.

Credits

This exhibition was brought to life by Danielle Triggs, Megan Cooper, Jennifer Lee Alice Whalley, and Tiffany Rhoades. Educational Activities by Hillary Hanel Rose.