Over the course of my Spring Break back in March of 2023, I had the opportunity with the support of the McGrath Global Research Grant provided by Katie McGrath, the JJ Abrams Family Foundation, and the Provost’s Office at Simmons University to travel to Washington D.C. and to spend several days exploring the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, arguably one of the the primary learning centers in the United States about the Holocaust.

The aim of this exploration was two-fold. First, I scoured the museum displays regarding any information related to girl’s experiences during the Holocaust. Due to extensive funding, the majority of the archives associated with this museum have been digitized and are available online. I worked deeply with these archival materials (in particular, written and oral histories) to uncover examples of girlhood during the Holocaust. While at the museum itself, I took careful note of the displays and information that I had not uncovered through my own research that I or other researchers could further expand upon and use to supplement the exhibition currently being developed by the Girl Museum.

However, the second aim of my exploration of the museum was perhaps the more interesting of the two. I spent much of my time in the museum examining the ways in which the historians, exhibition designers, and authors of the supplemental materials presented girlhood taking place within the context of the Holocaust. The US Holocaust Museum is full of information about all aspects of the Holocaust, from its ideological roots to actual video recordings of the camps themselves. Since I was able to spend a few days combing through the museum, I decided to spend the first day in the museum exploring it from the perspective of just a normal patron, not looking specifically for girls or girlhood in the materials. I gave myself a time budget and focused mainly on the large text that told the overarching histories that could be easily seen.

An initial walkthrough of the museum I must admit left me quite dejected. Of the dozens of displays, the only one dedicated specifically to a girl or exploring girlhood on its own was a small display discussing Anne Frank, arguably one of the most recognizable girls linked in the American public’s mind to the Holocaust. As I wandered through and read the overarching text, there were mentions of children and some instances where girls were mentioned, but focusing on the overarching text left much to be desired in terms of understanding the girlhood experience during the Holocaust.

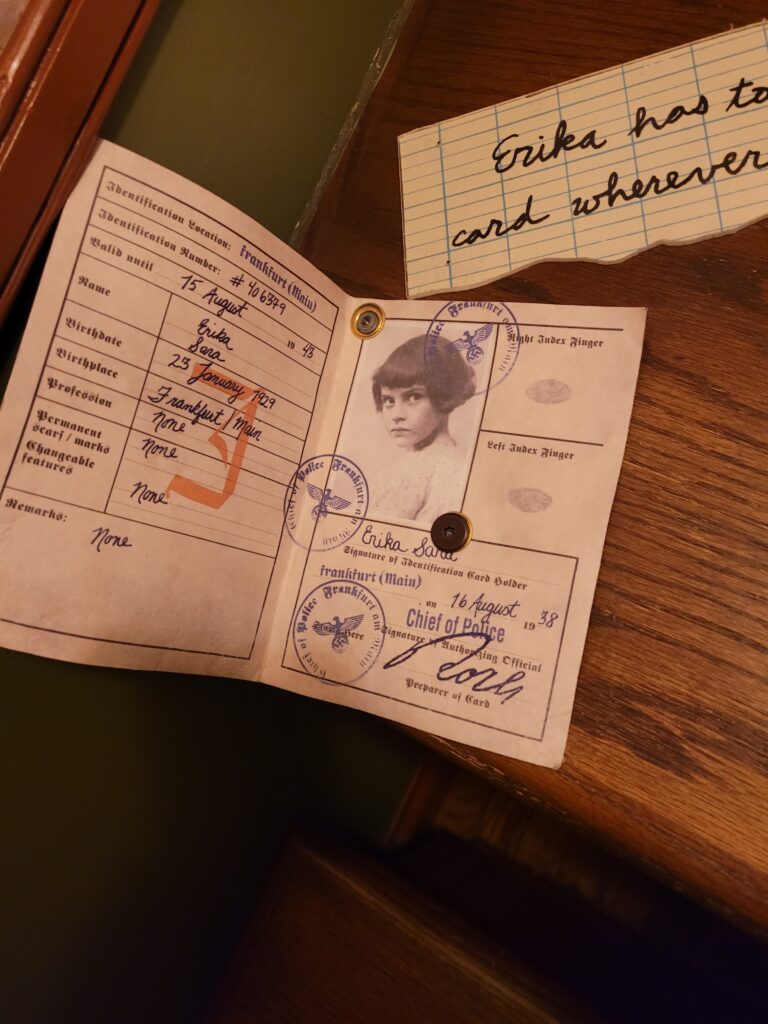

One exhibit which I did explore in full that first day however was the children’s exhibit, titled “Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story.” This tactile, hands-on exhibit, separated from the main exhibit space, provides children with a look into the life of a fictional Jewish child named Daniel in the events leading up to the Holocaust. As I walked through the simulated scenes, one factor that caught my eye was the presence of Erika, the young girl in this fictional family. The story being told is from Daniel’s perspective, but Erika features prominently. Scenes display her dolls, her sewing materials, and her identification card, and she is frequently referenced in Daniel’s diary entries that children can read.

The exhibit follows the family as they are forced from their home in Germany into a Jewish ghetto and eventually into a concentration camp. The video displayed at the end of the exhibit, in a room simulating the entrance to a concentration camp, features Daniel explaining that in the camp, his mother and sister were murdered. As I walked out of the exhibit, I couldn’t help but wonder about Erika; a fictional girl, an amalgamation and analogy for all of the other girls who had come before her. Was she the only counterpart to Anne Frank?

The next day in the museum, I approached the exhibits from a much more focused and historian oriented perspective. This day was much longer (spanning largely from opening to the closing of the museum in the evening). I read every piece of signage, examined every photograph and artifact, and recorded every name I found. And while the day before had been filled with disappointment, this day was filled with wonder. I found girls in the small booklets one receives at the beginning of the museum that allows you to follow real individuals in the Holocaust, in displays discussing the concentration camps, and in the many forms of resistance that rose up to oppose Nazi ideologies.

I found Nita Nathans, a Jewish girl hidden away from Nazi persecution and who was reunited with her family after the war. I found Antonia Donga, a sixteen year old Sinti-Roma girl whose photographs are among the hundreds taken by Wilhelm Brasse and hidden from the Nazis at the end of the war as evidence of the reality of the Holocaust. And among these named girls, I found dozens of unknown faces: from other young girls in the Brasse collection to the photograph of a young child of a German woman and African soldier to the artistic hands behind the children’s drawings from the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Once I went looking for them, I found them everywhere, in every facet of the museum.

Historically, there has been a desire to relegate women’s history to a subsection, largely removed from the wider and more influential narratives. This problem is even more greatly exacerbated when studying the history of girlhood. While certain organizations, such as the Girl Museum, are dedicated to preserving those stories and prompting discussion about the importance of understanding girlhood within the wider discourse, this designation as “lesser” history tends to leave girls from the historical narrative altogether.

Initially, it appears that the Holocaust Museum is just another perpetrator of this trend of excluding girls in historical presentations. Compared to the larger narratives present, girls appear tangentially connected. However, as I scrolled through the dozens of photographs I had taken of display placards and artifacts linked to girls and girlhood from the Holocaust museum, my appreciation for the museum’s choice to not create a section solely for exploring girlhood grew.

Why did it matter?

Because to separate figures like Nita and Antonia from the larger context would confirm the notion that girlhood history is somehow separate from the larger currents at play. Girls were present in both active and passive roles in every aspect of the Holocaust: from life in the camps, to the girls in the Nazi Youth clubs, to the girls whose families hid targets of Nazi hate. There is no one narrative that can capture the complexity of girlhood in the Holocaust. Not in a way that would do justice to those historical figures, and especially not in a museum with such a large scope. By allowing them to exist within their contexts, the museum challenged the intellectual roots that have demeaned the history of girlhood for so long: they were there. In every element, in every facet of history, they were there. In nearly every civilization, the narrative has been dominated by male perspectives, but even with these, women and girls can be found, if only one is willing to search for them.

The story may be Daniel’s, but the true beauty is knowing that Erica was there practically every step of the way, and that her story matters too.

-Robin Laurinec

Junior Girl

Girl Museum Inc.